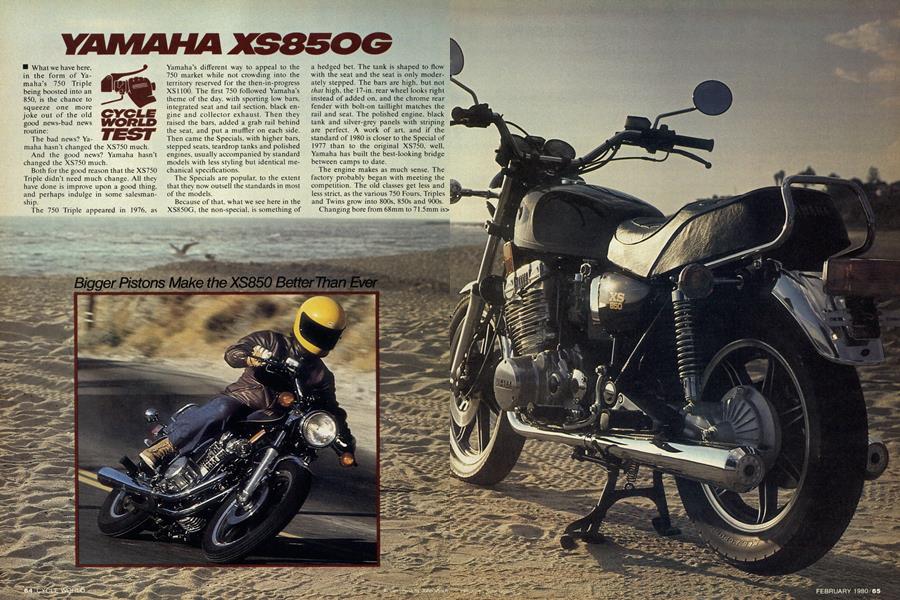

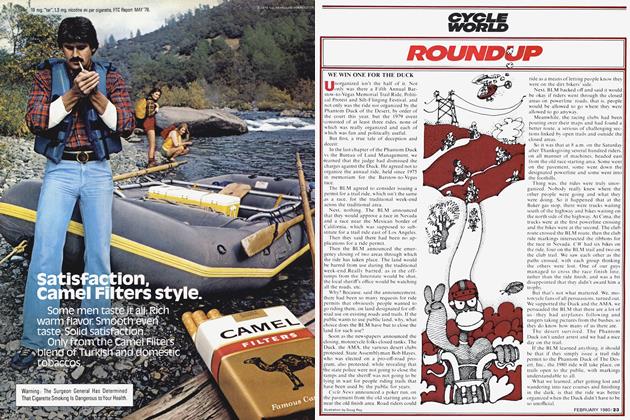

YAMAHA XS850G

CYCLE WORLD TEST

What we have here, in the form of Yamaha's 750 Triple being boosted into an 850, is the chance to squeeze one more joke out of the old good news-bad news routine:

The bad news? Yamaha hasn't changed the XS750 much.

And the good news? Yamaha hasn’t changed the XS750 much.

Both for the good reason that the XS750 Triple didn’t need much change. All they have done is improve upon a good thing, and perhaps indulge in some salesmanship.

The 750 Triple appeared in 1976, as Yamaha’s different way to appeal to the 750 market while not crowding into the territory reserved for the then-in-progress XS1100. The first 750 followed Yamaha’s theme of the day, with sporting low bars, integrated seat and tail section, black engine and collector exhaust. Then they raised the bars, added a grab rail behind the seat, and put a muffler on each side. Then came the Specials, with higher bars, stepped seats, teardrop tanks and polished engines, usually accompanied by standard models with less styling but identical mechanical specifications.

The Specials are popular, to the extent that they now outsell the standards in most of the models.

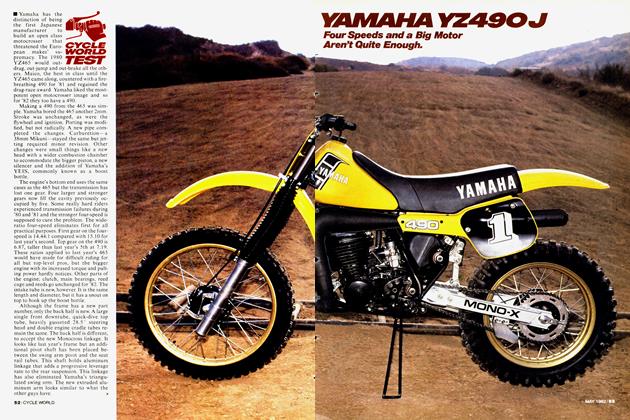

Because of that, what we see here in the XS850G, the non-special, is something of a hedged bet. The tank is shaped to flow with the seat and the seat is only moderately stepped. The bars are high, but not that high, the 17-in. rear wheel looks right instead of added on, and the chrome rear fender with bolt-on taillight matches the rail and seat. The polished engine, black tank and silver-grey panels with striping are perfect. A work of art. and if the standard of 1980 is closer to the Special of 1977 than to the original XS750, well, Yamaha has built the best-looking bridge between camps to date.

The engine makes as much sense. The factory probably began with meeting the competition. The old classes get less and less strict, as the various 750 Fours, Triples and Twins grow into 800s, 850s and 900s.

Changing bore from 68mm to 71.5mm is> the most economical way to keep the Triple in the game, so that’s what they did.

Increased displacement serves another purpose, as it’s the logical way to get more power or, in the case of 1980, to get back the power lost in meeting the emissions rules.

The Yamaha Triple is just right for both goals. When it was designed, the idea was to deliver useful power, mid-range punch and pulling power, as opposed to screaming your way to the winner’s circle. The Triple was built for more torque and fewer revs, so making it larger doesn't hurt the top end at all.

Actual displacement of the 850 is 826cc, a size dictated by the logical move of making the 850 almost exactly three-quarters of an XS11 Four. Same bore and stroke (71.5 x 68.6 mm), same pistons, and although the combustion chamber and valve timing were changed, they were changed to duplicate the larger engine. Compression ratio is still 9.2:1.

The 850 carburetors are Hitachi CVs, chosen after competition with Mikuni, who built the carbs for the XS750. The Hitachis have three jet circuits, compared with two for the Mikunis, and the new carbs were picked because they have good driveability while meeting the EPA rules.

The other changes are in the form of beef. Most visible is the oil cooler, standard equipment. The lines are routed from and back to the oil filter, and total oil capacity is increased, from 3.3 qt. to 3.5. The 750s have earned a reputation for reliability and we'd guess the cooler is there for insurance or rider confidence for those long rides with full fairing.

The primary Hy-Vo-type chain has been widened from 1 in. to 1.25 in. to handle the extra torque and there have been small changes in the transmission, both to overall gearing and its smoothness. Overall gearing has been raised from 5.71.1 in top gear to 5.52:1 by switching from a 30 to 31 tooth gear on the output countershaft. While this affects all the ratios, first gear has also been raised further by changing the internal gearset from 32/13 to 32/14. However, the overall road gearing, apart from first gear, is virtually unchanged because the smaller diameter of the 17-in. rear wheel drops the gearing by an equivalent amount, giving about 4400 rpm at 60 mph for the 850 vs 4500 at 60 for the 1979 750.

Of more importance though is that Yamaha has paid attention to the driveline smoothness. None of the Triples (or the 1100 four) have been famed for a snatchfree and silent drive. But with the XS850G, the factory has got as close as they can to the standard set by Suzuki’s GS850 shaft by the simple process of removing the spring-loaded damper on the countershaft behind the gearbox.

To combat the possibility of excessive oil consumption that has bothered the Yamaha Triples since they were introduced, a new type of oil control piston ring has been used on the 850. Made by Riken, its design removes the chance that the middle spring spacer can be overlapped during assembly so that the upper and lower oil scrapers press effectively into the ring groove shoulders.

As the standard model of the two 850s. the 850G has a centerline front axle, that is, lined up with the sliders. Only change in back is a relief in the driveshaft housing that also serves as the left side of the swing arm. Didn’t take much and it clears the 4.50 x 17 in. tire just about the way the older shaft housing cleared the 4.00 x 18. Still, there’s enough room for the new Special to sport a 16-in. rear tire. Wheels are cast alloy and the brakes are triple disc. The tires, Bridgestone Mag Mopus, are tubeless, something Yamaha has resisted until this model year. They perform well, and offer longer tread life, we're told, although that’s something only time can confirm. The 17-in. rear tire does increase load capacity, though.

The suspension has some extras of the kind quickly becoming standard equipment for the big sports and touring models. The forks have air assist and the rear shocks have adjustable damping, with three positions on a hand-dialed wheel. The adjustment alters compression and rebound damping in the same degree. The spring preload can still be set for a choice of five variations as before.

The duplex cradle frame isn’t changed at all, near as the eye can tell. Steering head rake is 27°, half a degree less steep than last year, and trail is increased from 4.8 in. to 5.16. Wheelbase is still 57.1 in. and overall length is an added 1.3 in., apparently the result of the different taillight.

The seat has double latches and removes instead of swinging up for service, a change we don’t like. The dual mufflers are 4 in. shorter than in 1979, which looks nice. The dual horns are mounted one to each side of the fuel tank’s lower front, which doesn’t look nice. The super self-canceling turn signals appear on the 850G and the steering head lock is still hidden on the steering head. Remarks about that vs. other factories with integrated locks (used on the Yamaha Specials, also) draw vague references to laws in other countries. Nonsense. Yamaha builds completely different models for some countries. They just don’t think the buying public will bother with locks, so they take the easy way out.

Standard on the 850 this year is a quartzhalogen headlight, the same unit used on the Special last year. Again, there's the required 85 mph speedometer. There's an awkward helmet lock at the rear of the seat. There’s still no clutch interlock on the starter. And the oil pressure warning light is reserved just for oil pressure this year so a burned out taillight won't cause a rider to panic and pull the clutch lever in and hit the kill switch.

In sum. a sensible series of changes to meet current rules and current public appetites.

The 850G works as well as the changes imply.

Starting is normal EPA. full choke on a brisk morning w ill let the engine fire up on a few spins and will keep it running fast enough for the rider to buckle helmet and pull on gloves. When the chill is off. though, the half-choke position doesn’t quite keep the throttle cracked enough, so you must motor away with the lever at half for the first mile. This can be confusing, as the mixture at low' revs and low load is weak, right on the edge because the emissions levels must be controlled, and if the choke is turned off too soon the engine w ill die at the first light. Once warm, no problem.

Uh. well, maybe a little bit of a problem. CV carbs tend to become confused on light loads and the engine will surge some, on and off without throttle variation, at less than 2500 rpm at light load. The rider soon comes to deal with this by not letting the revs and power demand get into the weak range.

What the 850 likes is work. The 750s sometimes felt like three quarters of a Four. The bigger pistons seem to be their own flywheels and the engine is smooth and even, just as a Triple with 120° crankshaft is supposed to be. from two thou on up.

Performance hasn’t suffered. The 850G did the quarter mile in 13.35 sec. and went through the traps at 98.25 mph. The 1979 XS750's times were 13.33 sec. and 101.12 mph. The 850 weighs more than the 750. so we'd guess from trap speeds that the 850 has just about the same power, and that the gearing changes account for 0.1 sec. slower E.T. For daily use, the 850 has more power at road speeds, which means the loss at the drag strip is more than worth it.

Fuel economy was astonishingly good. Everything the book says about getting more miles per gallon from a big engine turning slower w ith the throttle more open works. The big Triple did 47 mpg on the CW mileage loop, edging out the XS750. and the Suzuki GS850 as well as the GS750. The 4.5 gal. tank gives the 850G a useful range of 200 miles or so.

The numbers don't show the other good things about this engine.

The exhaust note is as pleasant as always. The govt's proposed limits are still pending, while the factories prudently work their way down the decibel scale, but although this means the Fours are muted to the point of not having any exhaust note at all. the Triple retains character. There is a hint of power under control, 3 beat as unique in its way as those of the big Twins.

What works best is the torque, great heaping leaps forward of the stuff. First gear is just on the high side of right and it takes a crack of the throttle to get off the mark but then each gear gives a solid city block's lunge. There’s no need to wind into the red zone, nor to shift down for performance. Twist the throttle and away the 850 goes.

We had on hand at the same time the turbo-charged XS750 described last month. More power, better times at the strip and other riders hardly dared look at the monster when you rolled up to a light.

But in real life, open the throttle of the turbo and the thing falls flat until boost builds up. followed a few seconds later by more power than you can get away with.

The 850 has instant response, in the right amount. Nobody here would swap the 850’s brand of go for the turbo’s.

Vibrations are not a Triple’s problem. Not with the 120° crank. No two pistons start or stop at the same time, so there is no shake or buzz. What there is, is some rocking around, engine on mounts, and a tingle, more like that of a big Twin but w ith lower amplitude, higher frequency. It goes with the exhaust note and nobody minded much.

The driveline change isn’t a complete success. The 750. and the XS11. are know n for play in the line as well as a clunk between first and second. Both are still there in the 850.

But the clunk is reduced. More like a click, and the rest of the shift pattern, up or down, is, well, not like the of hot-knifethrough-butter, but not bad. >

Some of the cause may be the clutch. The 850's clutch has thinner friction plates and thicker metal plates, the better to cope with the heat that comes from a larger engine.

The clutch worked well on the road, although it was as reluctant to completely release as was the 750 clutch, which is part of the clunk problem. Because first gear is higher than before, and the final drive ratio is higher, and the 850 weighs 10 lb. more, getting off the line is a strain and we did in the clutch during the track testing. This surely was a result of the all-out sessions rather than the machine itself, as our owner surveys don't show the 750 clutch as being a weak link. On the other hand, we subject every test bike to the same routine, and most of them come through intact.

What the 850 rider can do about the rough shifting is fan the clutch, jab the lever and roll the throttle off then on. quick as that. The reward will be smooth and silent shifts.

Takes effort, though, and while sometimes it's fun to practice getting the trick right, other times you’d just as soon not have to work at it.

The 850’s driveline is better, shifting is quieter than before, but neither is as good as that of the head-to-head rivals like the GS850.

Aided by a low seat, same height as the XS400's. the 850 feels like what it is, a 750 enlarged. The 850 feels small, compact and muscular. It doesn’t feel light, and it doesn't ride light.

Steering rake is about average for modern bikes and the wheelbase is shorter than most machines in the 850’s weight class. That should mean quick steering.

Instead, the 850 steers slowly. It steers well, in the sense that it tracks straight at speed, doesn’t fall into corners and will hold the chosen line on a fast turn, but the weight can be felt. Sure-footed is the word that comes to mind. Nimble is a word that doesn't come to mind. The suspension aids, the air caps and damping controls, are there for touring and weight control. Set for full hard, all the way on the preload. 10 psi on the caps and #3 on the dampers, and the ride is firm. With the springs on soft, the airfork on no pressure and the dampers on #1, the ride is soft. At neither extreme does the 850 slam into turns like an TZ, or even like the better sports 750s. At eight-tenths of maximum speed for a series of turns, the 850 is going as fast as its weight and configuration wants it to go, and pushing beyond that would be taking a perfectly good bike out of its element.

The handlebars are no helpt, incidentally. They are rubber mounted, which surely keeps some of the vibrations at bay. but while they don't feel flexible under way. the height and bend is wrong for pitching the bike through the twisty parts, and the isolation of bars from forks may enlarge the 850's dislike for telling the rider just exactly when the front tire has reached its limit.

The scorecard shows the 850 Standard’s seat rated at 150 miles, that being the distance before the riders here got serious about making up reasons for stopping. The position is right, the shape isn't bad, we just wish people would quit making it impossible to shift about while in motion.

The Yamaha’s front brake lever incorporates a machine screw and locknut at the point of contact with the master cylinder. With the adjustor, the rider can make lever travel translate into strong brake action at any distance from the grip that he wants. But the Yamaha’s rear end locks and comes around to the left under severe braking. Because the rear wheel is offset to the right about % in., applying the rear brake makes the rear wheel pivot around the bike’s center of gravity. Under emergency stop conditions, that makes the Yamaha more difficult to control.

Our test 850 had an awful squeal in the front when delivered, the sort of yowling that makes you sure the whole crowd is pointing and giggling.

The XS750 was a good bike, and a popular bike. It was the star of CW's first owner survey because more XS750 ow ners wrote in than did the ow ners of any other model.

The XS850 is a fitting replacement. All the strong points, the torque, the comfort and the sound, have been made moreso. while the faults, like the rough shifting, have been smoothed out if not eliminated.

Would we trade our 750 for an 850? Yes.

YAMAHA

XS850G

$2849