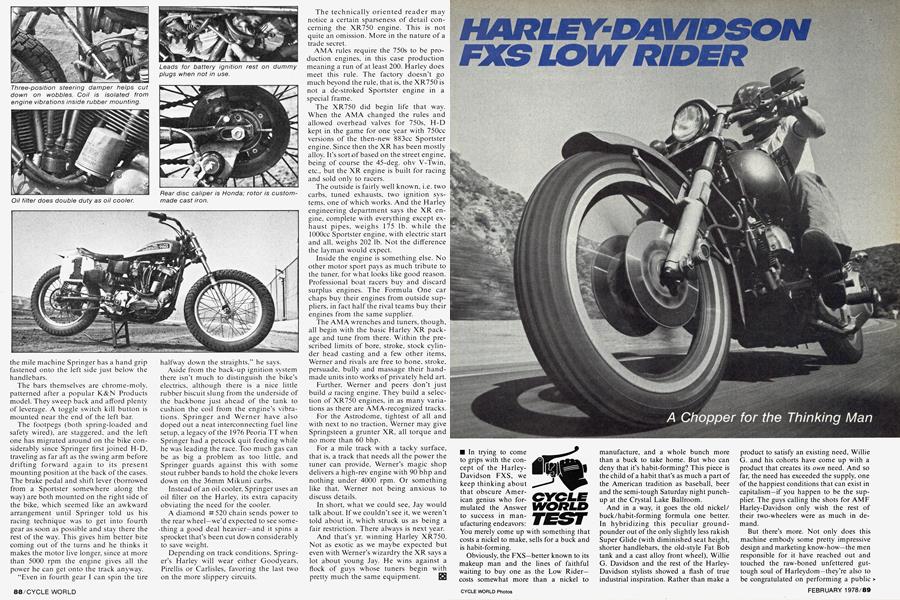

HARLEY-DAVIDSON FXS LOW RIDER

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Chopper for the Thinking Man

In trying to come to grips with the concept of the HarleyDavidson FXS, we keep thinking about that obscure American genius who formulated the Answer to success in manufacturing endeavors: You merely come up with something that costs a nickel to make, sells for a buck and is habit-forming.

Obviously, the FXS-better known to its makeup man and the lines of faithful waiting to buy one as the Low Ridercosts somewhat more than a nickel to

manufacture, and a whole bunch more than a buck to take home. But who can deny that it’s habit-forming? This piece is the child of a habit that’s as much a part of the American tradition as baseball, beer and the semi-tough Saturday night punchup at the Crystal Lake Ballroom.

And in a way, it goes the old nickel/ buck/habit-forming formula one better. In hybridizing this peculiar groundpounder out of the only slightly less rakish Super Glide (with diminished seat height, shorter handlebars, the old-style Fat Bob tank and a cast alloy front wheel), Willie G. Davidson and the rest of the HarleyDavidson stylists showed a flash of true industrial inspiration. Rather than make a

product to satisfy an existing need, Willie G. and his cohorts have come up with a product that creates its own need. And so far, the need has exceeded the supply, one of the happiest conditions that can exist in capitalism—if you happen to be the supplier. The guys calling the shots for AM F Harley-Davidson only wish the rest of their two-wheelers were as much in demand.

But there’s more. Not only does this machine embody some pretty impressive design and marketing know-how—the men responsible for it have reached out and touched the raw-boned unfettered guttough soul of Harleydom—they’re also to be congratulated on performing a public service. Sure, those of us accustomed to the visceral pleasures of today’s missile-quick, cat-agile superbikes don’t have much time for the Low Rider’s ponderous progress. You don’t really need the little emblem on the cases to tell you that Harley-Davidson dates its machinery to 1903; there are plenty of reminders bolted right into the frame. But we must judge everything from a standard of some sort, and the standard that inspired the Low' Rider is your basic chopped-up Harley, with all those refinements like springer or girder forks and hard-tail arrangements designed to keep one as close as possible to Mother Earth, kidneys or no kidneys. Measured against this, the Low Rider looks like the very pinnacle of two-wheeled modernity. Just look at it. Instead of the spool front hubs (with no brake) you see on a lot of choppers, your Low Rider has twin discs. Maybe you need a grip like Charles Atlas to make ’em work, but the point is they’re there. And maybe you can get your hindquarters closer to the ground by dispensing with non-essentials like rear suspension, but your Low' Rider justifies its trade name with a seat height of 27 in. and change, which is close enough to suit us.

Considered against contemporary machinery, the Low Rider gets marks that are only passing in a number of departments. The chopper look has made this bike a real handful to manage around town. This is because of the extended forks (ironically, in light of Harley’s American motif, these are made by Showa, and the pumper carbs are Keihin) and the short handlebars, which conspire to make the Low Rider quite heavy-headed in slow going, and no fun at all when the bumper-to-bumper stuff starts. The forks don’t seem at all disposed to respond to the various small irregularities in the road surface—the tech ed says they display more seal drag than many bikes have damping—and the rear shocks are much too stiff for extended solo riding.

Handling isn’t anything to write home about either, although it improves considerably once the Low Rider is moving 20 mph or better. The bike seems best on long, constant radius sweepers, which is probably a function of the substantial (63.5-in.) wheelbase. A couple of the barnstormers actually got down to scraping stuff—the left side peg and the exhaust on the right—but even in the most favorable kinds of curves the Low Rider could easily be provoked into a series of sullen wallows. The Goodyear tires served well, but the bike simply doesn’t like being twitched around.

The engine. To anyone with a taste for high rev twincam Triples and Fours, Harley’s indestructible V-Twin is a museum piece. It bears a more-than-passing resemblance to the first Big Twin, first offered in 1923 and even though H-D’s R&D people have all sorts of nifty designs for updating the old 74-in. shaker they'll probably have to file petitions with the FTC, SEC, ACLU and the Smithsonian Institution before they can touch a single, precious pushrod. After all, the 74 isn’t just a powerplant, it’s a national institution. Tampering with it would be like hiring an interior designer to pep up the decor at the Lincoln Memorial or spray-painting the Statue of Liberty neon pink. Sacrilege.

Living antique or not, though, there is an undeniable appeal about this pow'erplant as it goes ka-chunking about its business. For one thing, it’s a constant source of diversion at stoplights, where you can pass time counting the engine’s pulses at idle. We make it to be about nine per minute on average, although this figure can vary according to phases of the moon, activity along the San Andreas Fault, rutting season of the bull elk and the other mysterious earth forces that seem to be embodied in the V-Twin. And for another thing, there’s what this engine can still do as well as anything else in the biz; we calculate that Harley-Davidson V-Twins account for 37.6 percent of the world’s known motorcycle torque reserves. In fact, if AMF ever elects to get out of the motorcycle game we look for the company to come out with a dandy line of small V-Twin tractors.

You will note that there’s no redline on the tank-mounted tach (tach and speedo are both heavily cushioned in rubber to isolate them as much as possible from the great pulses of the V-beast thumping away below' them). There’s no redline because you don’t need one—the engine will tell you w'hen it’s being overworked, and there’s no mistaking this message; just be alert for the metallic taste of your fillings as they pop loose. >

HARLEY-DAVIDSON FXS

$4180

The pulsing is pleasant at normal cruising speeds, however, which are achieved with the V-Twin turning between 2000 and 3000 rpm. This not only lends itself to engine longevity, it makes for fuel economy that’s surprisingly good in a bike as big as this one. Surprising is the word for the quarter-mile times, too. In the stoplight wars, the Low Rider is about as useful as a skateboard, but all the same it’ll turn 15-sec. quarters, which is faster than anything coming out of Detroit these days. We wish the bike’s stoppability matched this modest go-power. Along with handling, it’s one area where any two-wheeled machine should be up-to-date, no matter how strong the manufacturer’s ties with the past. And we think the brakes already on the bike would work better with different controls. The lever for the front brakes is angled much too sharply away from the handlebar, making a difficult reach for anyone with small or even average-sized hands. (Ditto the clutch lever.) The rear brake pedal, angled up at about 40 deg. and reminiscent of the Good Old Days of running boards, foot clutches and hand shifters, is hard to get to in a hurry when you’ve been cruising along with your feet stuck out on the forward set of pegs.

Those forward pegs are a big part of what makes this machine fun to ride, even though this is diluted considerably by the fact that this riding position limits access to half the bike’s controls and is only comfortable for riders long-legged enough to wrap their right legs around the air cleaner. If you can accomplish this, then there you are, Joe Cool surveying the passing scene with the comfortable disdain of a man who has somehow managed to get his favorite armchair to levitate. The Low Rider’s armchair drew mixed reviews—it apparently suits some anatomies and not others—as did the passenger seat. The solo ride is harsh, but improves considerably with company (see the tech ed’s comments on the shock data panel). And since this piece grows progressively less comfortable to sit upon as its velocity increases, it doesn’t really seem to matter much that the seating position makes a small sail out of the rider. Bolt upright works OK on a cruiser, and if you want to do something other than cruise you’ve come to the wrong store.

The sissy bar, incidentally, is not part of the basic bike’s inventory, but we feel it really finishes off the look of the whole machine. It’s also functional; the padding is good, and the supports are fabricated from the same solid stuff one finds throughout the bike.

There are other nice touches. The kickstand locks into place with the bike leaned on it, which keeps the Low Rider from getting any closer to the pavement than it already is. H-D supplies a neat little oil cooler cover with velcro fasteners; you keep it snugged on around town to keep the oil up to operating temperature and remove it for freeway or expressway cruising. It seems to work.

The battery is consistent with the dimensions of the whole bike, and the starter motor has more than enough oomph to kick those 87mm pistons through their long strokes. The starting motor has so much muscle, in fact, that we employed it to run the Low Rider up a loading ramp when the petrol gave out during testing at Orange County International Raceway. But what the hell, you wouldn’t expect a pansy starting motor on a Harley anyway, right?

Overall finish is the Low Rider’s strong suit. The H-D flak mill calls the bike’s “visual impact almost brutal.” That’s a bit much, but whatever diverse thoughts we may entertain about the bike here we’re pretty much agreed that it looks right. Score it as another excellent packaging effort by Willie G. and the H-D styling gang, a blending of appealing traditional elements—the Fat Bob tank, the logo (it dates to H-D's earliest days), the overall profile—with modern licks like the crackle black finish on the cylinder heads, complete with highlighted cooling fins, and the slick Morris cast wheels. These last are about as good-looking a set as you’re likely to find anywhere.

The quality of the paint and trim ranges from high to excellent, as they should if your manufacturing goal is to produce “a powerful new statement in support of a biker’s individuality,” to quote the Harley party line again. After all. this is what the bike is all about: Style. Haute couture for the weekend easy rider. Self-expression for the guy who wishes he’d been young enough to work as an extra when they were shooting “The Wild One.” A chopper for sybarites who are either too committed to comfort or too smart (or both) to endure the real thing.

Never mind that the turn signals, pressure-on. release-off doodads, are extremely awkward to use in an actual turn. Never mind that the excessively fat, oak-hard grips seem to have been-produced on a lathe that was turned off too soon. Never mind that the high beam indicator, a bright red light mounted atop the right side of the tank, regularly draws catcalls from certain irreverent passersby. Never mind that you have to fill one side of Fat Bob before you can fill the other (if you want the tank completely topped up, that is) because the right side cap is vented and the left isn’t. Never mind that at almost any speed you have to pinch a mirror firmly between thumb and forefinger to get any idea of what’s going on behind

you. That stuff doesn’t have any bearing on how the whole package looks. It’s like owning a Pierre Cardin suit that looks super—provided you don’t bend over, or put your hands in the pockets. And it’s also reminiscent of the marketing sage who foresaw the public’s piteous need for prefaded jeans. Here’s the two-wheeled sequel—the mass-produced, pre-individualized motorcycle. All our critical criteria evaporate when they’re leveled against this machine’s basic reason for being. If the Low Rider wasn’t made out of such solid stuff, we can easily imagine it being turned out in the New York garment district. It’s apparel, not transportation. You don’t really ride a Low Rider; you wear it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Troubleshooters

February 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1978 -

Departments

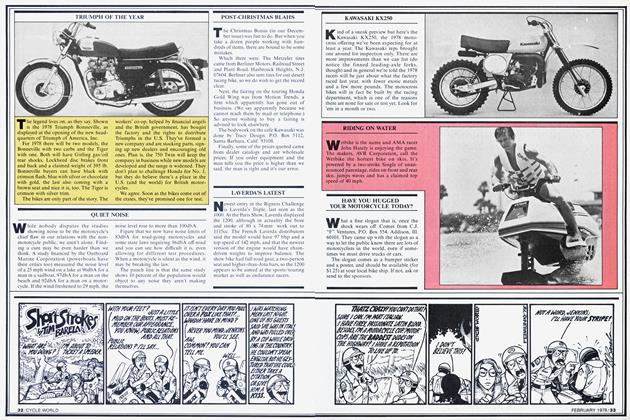

DepartmentsRoundup

February 1978 By A.G. -

Roundup

RoundupShort Strokes

February 1978 By Tim Barela -

Features

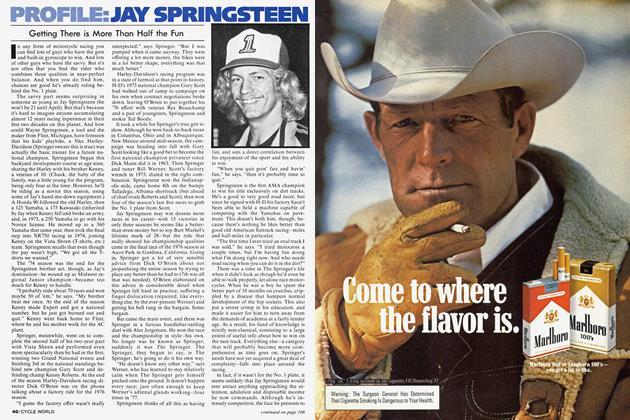

FeaturesProfile: Jay Springsteen

February 1978 -

Competition

CompetitionThoughts From the Back of the Wrecker

February 1978 By Peter Vamvas