THOUGHTS FROM THE BACK OF THE WRECKER

At least out on the track you can fall down and not get run over by a truck.

The rear shocks and springs are short travel, mounted nearly vertically just forward of the axle. Footpegs and mounts for the airbox and other accessories are new.

Front wheel is an 18-in. WM 1 rim. laced to a CB200 hub and wearing 2.50-18 tires, Dunlop in the case of our MT, although other racing tires can be used. (We had a lovely set of racing Yokohamas in the shop but project time ran out before we could use them.) The 9-in. mechanically activated disc brake also comes from the CB200 and stops the MT nicely.

The rear wheel is also an 18-in. WM1 rim for a 2.50 tire. The hub is from an ST90, with cable-operated drum brake from an XL 125. (Right, Honda didn’t limit its parts-bin dipping to the CR series.)

The MT is delivered with a three-piece suit; upper fairing, lower fairing and plexiglass windscreen. Also expensive, by the way, also because Honda isn’t making many of them and thus has a lot of investment to recover. Unlike the gearing, though, the MT owner can find a good variety of replacement panels in the aftermarket.

The assembled package is impressive.

So is the intent. Honda is offering a motorcycle for the enthusiast who'd like to go road racing on a racing machine, one as purebred as the bigger models ridden by Kenny and Steve and Gary, although a lot cheaper and slower and (by extension) safer.

There are several ways to evaluate a machine like this. One would be to sign up an experienced road racer, who could perhaps pick up a few trophies and give some secondhand luster to the staff. We know some guys who did just that. A fair approach and one that’s proved—we got our bike a little late, by the way—that the MT125R can win club races, in class and sometimes against larger machines.

We also know some guys who took their MT to the races . . . and lost. They believe that proved the MT isn’t competitive.

Unfair. The MT is a competitive racing motorcycle. It can run heads up with the Yamaha 125 racers, and with the occasional Italian machines at the club level.

So. Proving that the MT125 can win wasn’t a useful approach. Instead, we decided to see what it would be like for a novice road racer to enter club racing with the MT.

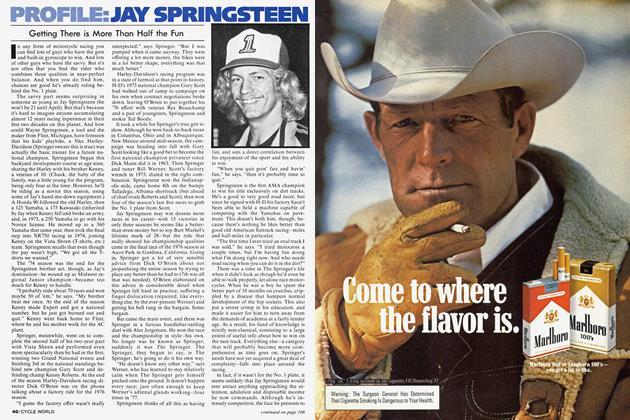

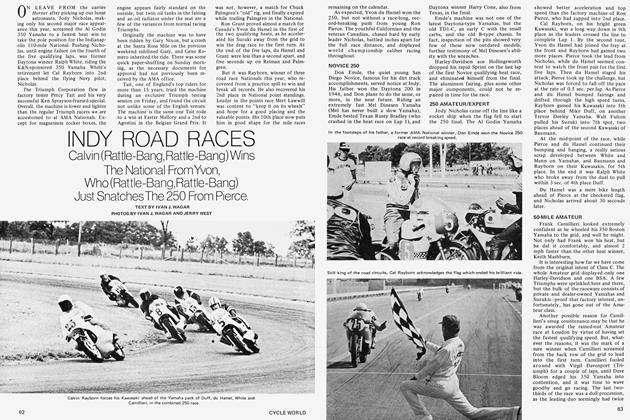

Our candidate was Peter Vamvas, Art Director and retired minicycle racer, performer of wheelies on machines like the Harley-Davidson XLCR. Peter is built like Kenny, he’s brave as Kenny. All he needed was the experience.

And now we take you to trackside . . .

So this is what road racing is all about; Sweat rolling off my balding pate and down the bridge of my nose, my glasses slipping down, I reach up to make an adjustment and ram the helmet shield, damn! No time now. Shaking my head to work the glasses back into place just as the starter waves us off . . . welcome to what it’s like out there.

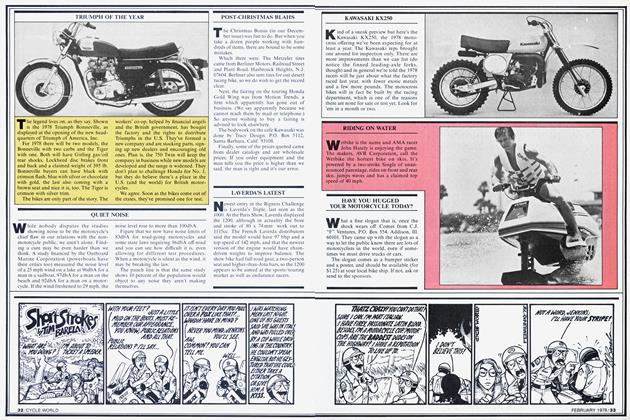

Out there is the track. Riverside International Raceway, the practice race for novice racers, sanctioned by the American Federation of Motorcycles. Out there is Honda’s MT125R, a racing bike for people who’d like to give it a go and not go too far.

This is new and strange. So is the MT, a cute little machine so small that when it’s 10 feet away it looks to be 100 feet away, a motorcycle that to the road rocket crowd seems like a would-be plastic model.

At the shop before the races we learned the basics; the engine wouldn’t run below 5000 rpm, it began to make power at 8500 or 9000 and things began to really happen at, say, 12,000.

No kick starter. With the bike on the stand, Len could spin the rear wheel with one hand and the engine would start right up. Rolling starts, with me at the clutch and throttle and Len pushing, seemed to take two miles, with lots of gasping and sputtering.

Then it was time for the games to begin. First, riders’ meeting. We (the novices) met in a giant cigarette box and were given a few pointers on racing bikes. Also we see our competitors. Soon all of us would be out on the track but it was here that we would silently gain the trust of each other. Out there, racing, there is plenty to worry about without wondering who’s going to take you into the wall. Oh, well, we would soon know all. An AFM official and Keith Code, a racer-turned-teacher, awaited the three or four questions the 20-odd novices could muster. We were eager. No time for questions. I do remember hearing about not following someone else and to try not to look like the pictures of Roberts and McLaughlin. Later on I overheard a warning to keep my hand on the clutch lever

going into Turn 9 at the end of the long straight. Something about the engine seizing when you back off from 12,500. Rear wheel locks and you wish you had better leathers.

Everyone was a competent rider. We saw that in practice. We practiced alone and with the larger bikes.

Zang! Zang! Zang!

Fierce thermals trailing the big bikes as they blew by, the smaller bikes caught in the spiraling slipstream of experience, not yet ready to hook up for the big ride. We were as yet only fringe players, not to be put on waivers.

My selection as staff racer was in some ways based on my size, in the context of the MT. When the bike was ordered, just who would do the riding was sort of left floating, while everybody made noise about how they’d love to, but ... I forgot to disqualify myself and there I was. I did want to race, didn’t I?

Peter Vamvas

My first ride on the MT was befitting a member of the motorcycle press. A nervous yet confident rush up a city street to the gap-toothed enlightenment of two rubber-jawed, beet-faced motorists in a pink and grey Rambler wagon.

That short run around the office was enough to show what a road racing machine is like. How different from a street bike depends on which street bike, but in general one would be advised not to carry groceries on the MT. Well, maybe chewing gum. But nothing else. It seems as if something is missing. Much is, but none of what’s been left off is missed.

This is a racing bike. In the hands of an experienced rider the MT will win and win big. The MT was made for Jody Nicholas. I don’t think they knew how to spell my name.

But what you really want to hear about is the race. Sure. And the crash. Yeah, I crashed. I suppose that the idea of crashing is what you think about most before racing. Getting off. Eating the load. Like all the instructions in a book, nothing counts till you’ve actually gone out and done it.

Novice race. First attempt off the line. My experience on bikes has included some gonzo runs at the drag strip, primarily those bikes that would staple your eyes shut. Those 12-sec. bikes. This little 125 would be easy. If it would start. They called the bikes to the line but Len was not there to push. Geez! Come on. In blind desperation I pushed and ran and jumped and all it did was sputter. Then at last I was yelling safely within my helmet, w'ords of praise and admiration for Len, who appeared just as the steam fogged up the visor.

The pipey pow'erplant finally spit into action and 1 gridded in the back of the pack trying to keep the engine running with one hand and push my glasses back in place with my other. I couldn't unsnap my visor with one hand so the only way to reach my glasses was to reach between my face and the inside of the helmet. My right hand was wedged in that spot between beard and helmet when the flag fell. Muttering loudly I eased the clutch out slowly, and even more slowly the bike began to move.

These little 125 hyperkinetic racers come on slow. You sit on the line with 8000 . . . 9000 . . . 10,000 eager rpm spinning unbridled between your ankles. The flag drops and you tip-toe away from the starting line, hoping for the clutch to catch up with the flywheel, all the time sounding—you and 30 or so other pretenders to the throne—like you’re breaking the sound barrier and you know if you put your feet up you will fall over.

Around me—(mostly ahead of me) the assorted bikes made their way to Turn 1 and through the esses to Turn 6. My bike came onto power after a series of frantic jerks on the bars, the way a kid wheelies a bicycle, accompanied by serious verbal threats to any bike that passed mine. I was losing control. The warnings about riding over your head were not being heeded. Racing meant catching the guy ahead of you. Into the heat of battle, with my eyes closed.

Once in motion the bike responded to the slightest of inputs. Certainly in my case I was not able to fully utilize the potential of the Honda. On speed alone the bike would reel in bike after bike. Each lap found me less tentative about the bike’s handling, braking, etc. Playing catch-up is a good way to learn. After the four or five laps were over I was exhausted, mostly from yelling, but 1 was also pleased with my prowess. The added dimension of competitors alongside at 100-plus w'as an inspiration. Oh. I finished well back but the parts were right. Now to rest and chew on an adrenal gland for a moment. Later the big race.

Between the races Jody Nicholas gave us some tips on gearing and jetting. Everyone is very helpful, especially wffien they know you're just starting out. When you become a threat. I imagine each rider must fend for himself.

I was surprised at the strain on my stomach muscles after only four laps. The prospect of the eight-lap main seemed unbearable. But all I needed w'as a good start. A quick raceway dog and a cola and I w'as ready. Rushing to the pre-grid, my crew together at last, w'e w'aited. NowI was a veteran of one race. The bike was a winner. Was 1? Len bumped me off for the w'armup lap and we gridded according to predetermined assignments. Most of us, that is. I knew nothing of this so 1 pulled up next to Jody in the second row of our class. We would race w'ith the 200cc production bikes and they w'ould start 30 seconds before our wave.

I would watch Jody to get the secret of the start. He made a few quick lunges w ith his upper body, feet up. knees in, and he was almost out of sight before I reached Turn 1. Still, my start wasn't too bad and I was in sight of the front 10 before Turn 6. There was much jockey ing for position and the closeness of the bikes in the corners was encouraging. Down the back straight, the MT’s strong powerband allowed me to pass one or two bikes, only to be repassed as I awkwardly got off the line through seven. Coming out of seven entering the main straight, the bike easily pulled past two riders and in the flowing left-hand sweeper before nine I saw 12.500 on the buzz counter. I don’t remember having my hand on the clutch as I backed off and downshifted (once? twice?) but there was a good feeling coming out of nine and up to start/finish in the first group of 125s (excluding Jody who was challenging the 200s by now)

continued on page 108

continued from page 51

For the next few laps it became apparent who I was going to race. The others were too far ahead to catch so four .then three of us settled in for a sprint to the finish.

Twice I bobbled badly. Once in the esses, I got on the wrong line, almost cutting off a faster rider and sending myself perilously close to the edge. I had to quickly jerk up out of my Phil Read squat and grip reality by the handful, edging the bike down the side lines, a motorized Mercury Morris high-stepping for extra yards. . . .

No time to daydream as I hurriedly regained my position between my rivals. Two laps to go and my speed in the straights made up for some of my ineptitude in the corners. I could not decide which riding style to use. Sometimes I would stay tucked behind the tiny fairing, other times I thrust my leg and knee out in a Skip Askland-like pavement scraper (except that the photos revealed more chance of hitting a bird than a curb).

Not certain of my actual place in the race, but quite certain it was in the top 10, I saw the white flag wave us into the last lap, the three of us holding our positions through one and into the esses. Oh, yes, my hands hurt from holding the grips too tightly and my glasses had been shaken all about. For that matter, my head was shaking, as was the raceway dog in my gut. But I was going to pass this guy ahead of me. My bike had the edge down the straight, as noted before, but I guess I had to beat him at his own game.

He was about 10 feet in front as we came through five into six. He braked just before going up the hill. At that point, because I had not backed off, I came up to his rear wheel, braked heavily, bottomed the forks and went straight up the hill and into the wall at a speed better imagined than proven. I had gone for it. I had wanted a slam dunk. And I had fouled out.

On the way back, riding on the wrecker, I felt no shame for crashing. Rather, there was a feeling of minor victory. I crashed. Not badly, but I did go down and I did get up again. It wasn’t so bad. The bike needed only minor repairs. My borrowed leathers were only slightly torn. My glasses didn’t even come off. OK, that’s done. Like falling down ice skating. Get it over with and get back up for more. At least out on the track you can fall down and not get run over by a truck.