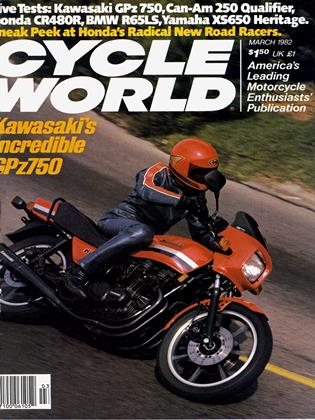

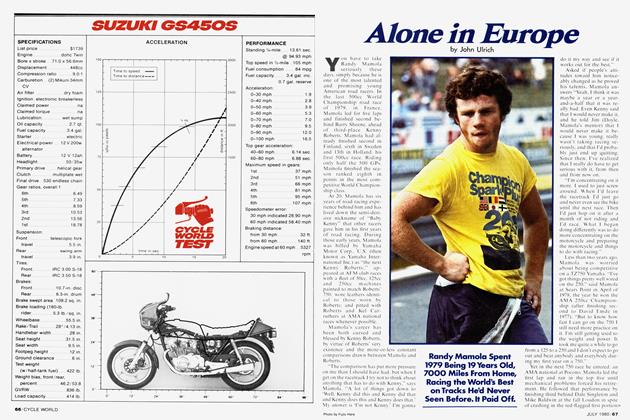

Honda's New Racers

John Ulrich

Imagine our surprise when the call came. Freelance photographer Mush Emmons was at Laguna Seca Raceway in Monterey, Calif. to shoot photos for Paul Newman’s race car team. So there’s Mush, laden with cameras and lenses, out on the course, when a motorcycle flies by.

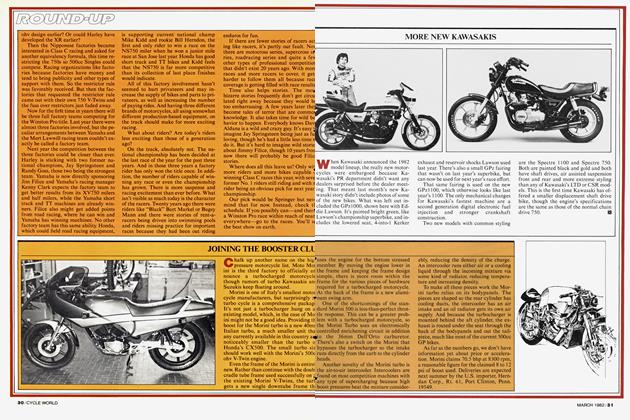

Not just any motorcycle, but the new two-stroke, three-cylinder Honda built for the 500cc World Championship, the very bike Freddie Spencer will ride in the 1982 championship series.

And here comes Mike Baldwin, newlysigned with American Honda for Superbike and AMA F-l racing, on an equallynew, V45 Sabre-based 1025cc V-Four four-stroke F-l bike with an odd, NR500like exhaust note, a mixture of two-stroke and four-stroke sounds produced by extremely high rpm.

Emmons didn’t pass out from the intensity of the discovery. Instead, he kept his eyes open and his finger on the shutter. These are his photos.

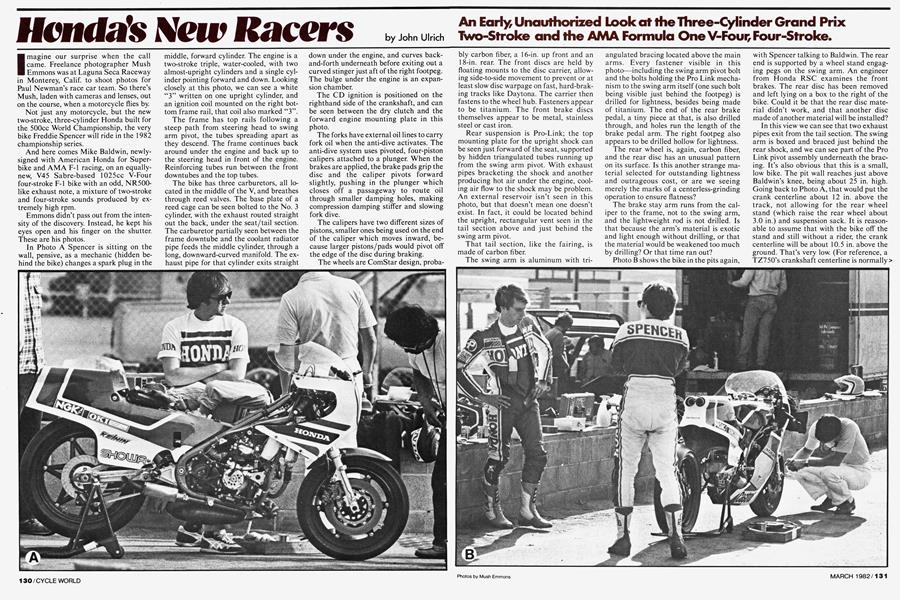

In Photo A Spencer is sitting on the wall, pensive, as a mechanic (hidden behind the bike) changes a spark plug in the

middle, forward cylinder. The engine is a two-stroke triple, water-cooled, with two almost-upright cylinders and a single cylinder pointing forward and down. Looking closely at this photo, we can see a white “3” written on one upright cylinder, and an ignition coil mounted on the right bottom frame rail, that coil also marked “3”.

The frame has top rails following a steep path from steering head to swing arm pivot, the tubes spreading apart as they descend. The frame continues back around under the engine and back up to the steering head in front of the engine. Reinforcing tubes run between the front downtubes and the top tubes.

The bike has three carburetors, all located in the middle of the V, and breathes through reed valves. The base plate of a reed cage can be seen bolted to the No. 3 cylinder, with the exhaust routed straight out the back, under the seat/tail section. The carburetor partially seen between the frame downtube and the coolant radiator pipe feeds the middle cylinder, through a long, downward-curved manifold. The exhaust pipe for that cylinder exits straight

down under the engine, and curves backand-forth underneath before exiting out a curved stinger just aft of the right footpeg. The bulge under the engine is an expansion chamber.

The CD ignition is positioned on the righthand side of the crankshaft, and can be seen between the dry clutch and the forward engine mounting plate in this photo.

The forks have external oil lines to carry fork oil when the anti-dive activates. The anti-dive system uses pivoted, four-piston calipers attached to a plunger. When the brakes are applied, the brake pads grip the disc and the caliper pivots forward slightly, pushing in the plunger which closes off a passageway to route oil through smaller damping holes, making compression damping stiffer and slowing fork dive.

The calipers have two different sizes of pistons, smaller ones being used on the end of the caliper which moves inward, because larger pistons/pads would pivot off the edge of the disc during braking.

The wheels are ComStar design, probably carbon fiber, a 16-in. up front and an 18-in. rear. The front discs are held by floating mounts to the disc carrier, allowing side-to-side movement to prevent or at least slow disc warpage on fast, hard-braking tracks like Daytona. The carrier then fastens to the wheel hub. Fasteners appear to be titanium. The front brake discs themselves appear to be metal, stainless steel or cast iron.

An Early, Unauthorized Look at the Three-Cylinder Grand Prix Two-Stroke and the AMA Formula One V-Four, Four-Stroke.

Rear suspension is Pro-Link; the top mounting plate for the upright shock can be seen just forward of the seat, supported by hidden triangulated tubes running up from the swing arm pivot. With exhaust pipes bracketing the shock and another producing hot air under the engine, cooling air flow to the shock may be problem. An external reservoir isn’t seen in this photo, but that doesn’t mean one doesn’t exist. In fact, it could be located behind the upright, rectangular vent seen in the tail section above and just behind the swing arm pivot.

That tail section, like the fairing, is made of carbon fiber.

The swing arm is aluminum with triangulated bracing located above the main arms. Every fastener visible in this photo—including the swing arm pivot bolt and the bolts holding the Pro Link mechanism to the swing arm itself (one such bolt being visible just behind the footpeg) is drilled for lightness, besides being made of titanium. The end of the rear brake pedal, a tiny piece at that, is also drilled through, and holes run the length of the brake pedal arm. The right footpeg also appears to be drilled hollow for lightness.

The rear wheel is, again, carbon fiber, and the rear disc has an unusual pattern on its surface. Is this another strange material selected for outstanding lightness and outrageous cost, or are we seeing merely the marks of a centerless-grinding operation to ensure flatness?

The brake stay arm runs from the caliper to the frame, not to the swing arm, and the lightweight rod is not drilled. Is that because the arm’s material is exotic and light enough without drilling, or that the material would be weakened too much by drilling? Or that time ran out?

Photo B shows the bike in the pits again, with Spencer talking to Baldwin. The rear end is supported by a wheel stand engaging pegs on the swing arm. An engineer from Honda RSC examines the front brakes. The rear disc has been removed and left lying on a box to the right of the bike. Could it be that the rear disc material didn’t work, and that another disc made of another material will be installed?

In this view we can see that two exhaust pipes exit from the tail section. The swing arm is boxed and braced just behind the rear shock, and we can see part of the Pro Link pivot assembly underneath the bracing. It’s also obvious that this is a small, low bike. The pit wall reaches just above Baldwin’s knee, being about 25 in. high. Going back to Photo A, that would put the crank centerline about 12 in. above the track, not allowing for the rear wheel stand (which raise the rear wheel about 3.0 in.) and suspension sack. It is reasonable to assume that with the bike off the stand and still without a rider, the crank centerline will be about 10.5 in. above the ground. That’s very low. (For reference, a TZ750’s crankshaft centerline is normally 15-17 in. above the pavement).

What we’re seeing here is an effort to make Honda’s two-stroke GP bike—the one they said they’d never build—as small and light and compact as possible. And as different as a competitive GP bike can be. This is a simple engine, in GP terms. In concept it’s like three water-cooled motocross Singles, bolted together across the frame with the outside cylinders nearly upright and the center cylinder nearly horizontal.

Why? Compare first with the current Yamaha / Suzuki / Kawasaki / Armstrong / Cagiva efforts; square Fours that aré narrow and long. Or the earlier generation of inline cross-frame Fours; short but wide.

The staggered Triple can be nearly as narrow as a Twin. You need space for three connecting rods but the barrels can overlap. And the engine is only one crankshaft long while a square Four is two cranks long. With the gearbox, rear suspension, swing arm, etc., being equal, the bike with an inline Triple will have less weight and a shorter wheelbase than a square Four.

This is unauthorized guesswork. We don’t know the angle of the cylinders, although we guess it’s more than 90° and less than 120°.

Next, there’s nothing in the rules that says you can’t have the outside cylinders displace 125cc and the center one 250cc and time the thing like a big V-Twin, but that would be beyond even what Honda experiments with. We figure the cylinders are of equal displacement and that the crank throws are 120 ° apart. There will be a staggered firing order but the power pulses will be as equally spaced as is practical. That in turn allows a lighter, more compact drivetrain.

Each cylinder has one slide-throttle carb and a reed valve. This bike doesn’t have the complexity of a works Suzuki and works Yamaha square-Four, with four separate, geared-together crankshafts and rotary valves. It doesn’t have mechanisms to raise and lower exhaust ports like a works Yamaha transverse Four. It is simple, and light.

The idea is to build a machine the size and weight of a 350 with more power. Sure, this engine will not make as much power as the other 500s, estimated to produce as much as 125 bhp. But the fastest 350s in Europe lap tighter tracks at times almost equal to those obtained by the best riders on works 500s. A World-Championship-quality 350 will make somewhere around 78-84 horsepower and weigh from about 235 lb. for really light ones to about 260 lb. for an average one. On the other hand, a competitive 500 weighs from 285315 lb.

If, by using the most exotic materials and design and by drilling every bolt and shaving every ounce, Honda can make this motorcycle weigh tlje same as an average 350—or about 260 lb.—then the 100 or so horsepower its simple engine can produce will be enough to make the bike competitive in 500cc World Championship races.

More than that, we can expect that the bike may even make an appearance in the U.S., ridden by Baldwin, perhaps on a tight track like Loudon.

It is a pretty bike, as seen in Photo C with Spencer aboard. (Note the small vent in the side of the fairing numberplate, probably ducting cool air to the ignition or the clutch.)

In Photo E, we see Baldwin sitting on the new 1025cc V-Four four-stroke, talking with Team Honda’s Jyo Bito. The fourstroke has the same anti-dive system seen on the two-stroke, and similar wheels and brakes. Each bank of two cylinders has its own 2-into-l exhaust system, one system exiting out the seat and another behind the right footpeg. The bike is liquid cooled, with fairing ducts to allow the hot air to escape. Looking at the seat/tail section, note the grill built into the top of the tail. That grill feeds air coming off the rider’s back (when the rider is tucked in) to an oil cooler mounted underneath.

In Photo F, we see Team Honda road race manager Udo Geitl looking at something while Baldwin sits, waiting. Notice the screened vent in the tail section, which allows air to the oil cooler to escape.

Photo G shows Baldwin and the new bike charging out of Laguna’s Turn Nine. It is clear from this angle that the bike is Pro Link with an unusual swing arm design. Two equal-sized arm assemblies are joined together to produce a single, triangulated unit. The Pro Link pivot can be seen just below the ball of Baldwin’s left foot. The ducting to remove hot air from the radiator is also clearly visible in this shot.

What isn’t visible is the engine. AMA Formula One rules allow anything within the basic guidelines (1025cc four-strokes, 750cc two-strokes with 23mm intake restrictors, unrestricted 500cc two-strokes) with no requirement for a production line base. That means that this V-Four Honda could be based on the new V45 Sabre, or it could be an enlarged NR500 with eight valves per cylinder and oval pistons.

Some sources familiar with Honda report that the engine in this bike is based on the street bike, and that it was actually running in March 1981, long before the debut of the street versions. They also say that the bike didn’t make enough power for Daytona 1981 and still doesn’t make enough power to be competitive. However, these photos were taken two months before Daytona 1982, so just maybe it will be ready this time.

Photo H shows Baldwin again, on a Honda Superbike based on the CB750F with a stock stroke and big bore (the stroke being shorter and the bore being bigger than was the case with the CB900F-based Superbikes used by Honda during most of 1981). The bike also sports the usual massive front forks but with a new-for-1982 16-in. front wheel and Michelin slick.