"On the Third Day I Wore My Racing Leathers... And Blended Right In."

October 1 1979 John Ulrich"ON THE THIRD DAY I WORE MY RACING LEATHERS... AND BLENDED RIGHT IN."

John Ulrich

My neck ached and my arms were pumped up from fighting the wind and wrestling the heavily-laden Yamaha XS11 through unending strings of left-right-left curves, turns, esses leading between stone houses, churches and bakeries that had seen at least three centuries of use. Winding down hillsides like water spilled from a well, the road is narrower than an average American residential street yet is a main route. Huge trees often mark the point where highway ends and farm begins. In the misty distance fantastic steeples and what look to be medieval castles break up the myriad shades of green glowing in the last rays of sunset.

The countryside is unbelievable, the road impossible, changing from cobblestone to asphalt to a mixture of the two. charging breakneck up and down hill, riddled with blind crests followed by fallingawav turns that make the bike feel weightless one second and like lead the next. Bizarre Citroen 2CVs (automobiles with bodywork introduced in 1948). flashy 1979 Matra-Simca sports cars, ancient BMW's with rowboat-style sidecars that look left over from World W'ar II. huge semi-trailer trucks and young girls on mopeds dodge each other and fight for lane space (the young girls usually winning), all the w hile forming a moving, unpredictable chicane for anybody riding a motorcycle at tw ice the posted speed limit.

Just ahead and leading the way on ¿in intricate route from Calais to Paris is Steve White, an Englishman who lives in Paris and is returning home after a trip to Scotland. We had met on the Hovercraft ferry between Raimsgate. England (near Dover) and Calais. France. Now W hite. 33. showers sparks as he drags his BMW R65’s engine guards in traffic circles and prompts involuntary gasps inside my helmet as he passes trucks, cars, bicycles all at once on cobblestone curves.

“Do you always ride like this?" I ask when 1 catch up at the first traffic signal we encounter.

“Yes," he replied. “Why?"

This is European touring.

I was halfway through a six-country, 3500-kilometer (2170-mile), three-week European tour, and I had already forgotten any ideas of American-style, full-dress, sedate, relaxed touring. My trip began (with a Yamaha borrowed from the German distributor. Mitsui Maschinen. Gm bH) on the autobahns, and the first thing that became obvious was that everything is different. There are no speed limits on the German autobahns, (which would be called interstate highways in America), and how fast people ride or drive is purely an economic question. The faster they drive, the more S2.00-a-gallon fuel they’ll use. and if they’re w illing to pay the price, they can go as fast as their vehicle will travel.

In Germany, people run their superbikes at 200 kph (124mph) with complete immunity, worrying only about tire life and running range. In countries like France, with a maximum speed limit on the tollroads of 120 kph (75mph), they ignore the speed limit and cruise as fast as they want anyway. You quickly understand whv European tourers like clip-on handlebars. rear-set pegs, tank bags and cafestyle fairings. Holding onto and steering an unfaired, heavily-laden motorcycle at speed is a great isometric exercise for neck and arm muscles, but it gets tiring after a few hundred kilometers.

It is. without a doubt, more consuming, more tiring, more demanding of concentration on a hundred things at once than real, on-the-raetrack racing. The roads twist and turn and climb and dive and the road edge is marked by a cliff or a gorge or a huge old tree or a canal or simply a stone barn six inches out of the traffic lane, and the surface is apt to change any moment from good to bad to unridable. The traffic is a mix of every kind of vehicle with every conceivable speed potential. Add in kids, dogs, intersections, traffic circles, rain and directional signs in foreign languages and the American traveler has got some problems to deal w ith.

You blink your eyes or roll off' the throttle for an instant to double-take a road sign in Germany and 10 guys blast past on superbikes—six of them with their girlfriends riding on the back —alternator covers on the ground and exhaust pipes and stands dragging lines on the alreadvscarred asphalt. Every one is wearing full leathers, and the girls have matching, color-coordinated leather suits, boots, and gloves.

Underneath it all. beyond the easy observation of fearless madmen on the road, is the inescapable fact that most of these riders are pretty good. You don't find many people riding superbikes who are afraid of the throttle or uncertain of their machine's limit. If they’ve survived on European roads long enough to ride a GS1000 or KZ1000 they must have learned something about riding hard and traveling fast, and it shows when you see them on the streets.

The effect of high (or non-existent, or ignored) speed limits shows in the skill level and alertness of automobile drivers as well. You may be riding 20 mph faster than most traffic on an autobahn, but before you can reach for the high-beam switch or need to touch the brakes the drivers in the left lane have already started to move out of your way.

You know you're in a foreign country when you keep wishing your XS1 1 had a sixth (or seventh) gear. Cruising along in fifth gear on a 1 lOOcc motorcycle just doesn’t seem natural when you look down at the tach and see 7000 rpm ( 1 12 mph). It also doesn't seem natural to spend $10 on five gallons of gasoline every 135 miles, or to get less than 30 mpg at a steady speed. And pity the poor soul whose machine burns oil. because in Europe a liter (1.06 qt.) can cost the equivalent of $5.00 at gas stations, a U-liter can about $3.00.

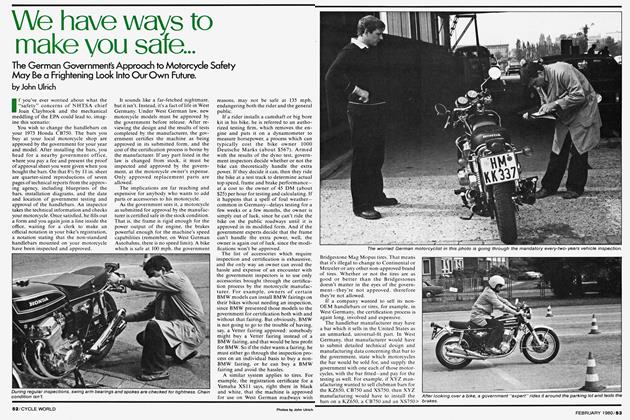

Western Europe in general, and especially Germany, is hard on vehicles. It suddenly dawns on you that you don't see any Volkswagen bugs in Germany—everybody has relatively new Volkswagen Golfs (the European version of the Rabbit). Audis. BMWs. iMercedes-Benz. Opels. Porsches. Old cars (and bikes) don’t seem to exist. The combination of speeds driven, road surfaces, weather and a tough, mandatory, every-two-years German vehicle inspection weeds them out. There also aren't many Japanese cars in Germany.

It's a different story with bikes. The Japanese wave has washed over most of Europe. The majority of bikes are from Japan.

“I used to have a BMW.” one German with an XS11 told me. “But the reason I would buy a BMW is comfort. This Yamaha has comfort and more horsepower, too.” Anybody who rides the autobahn appreciates power. Yamaha XS1 Is rule the autobahns.

* * *

The real action had started at the Contidrom. a huge Contintental tire test facility in Northern Germany. The Contidrom is the site of an annual motorcycle rally. This year, an estimated 30.000 people attended. Most camped in grassy meadows within the fenced facility, during the threeday event. Plenty of beer and a two-storyhigh campfire warmed the nights. With daylight, participants could wander through the parking areas checking out row-after-row of motorcycles, trick and not-so-trick. Or they could visit displays on tire construction and performance inside a large circus tent which doubled as concession stand and eating area. Off' in one paddock area was a display of vintage motorcycles. On one day a bunch of old timers wheeled out their precious DKWs. Moto Guzzis. Rudges. Panthers. Gold Stars and every other kind of aged European motorcycle and cut eight laps around the base of the Contidrom's 1.75-mile banked oval, the object being to turn several consistent laps at the same exact speed.

Along the main straightaway of the oval were periodic demonstrations of motorcycle handling and safety.

Brave souls could bring their motorcycle and enter several skill tests. One was a complicated field meet which required riding over a see-saw; riding along a straight wooden beam; placing three brass rings on posts while riding past; riding around a circle while holding the end of a wooden beam pivoted at the center, underneath a succession of three lower-and-lower limbo-style underpasses, and around a figureeight outlined with up-ended wooden blocks. The lucky rider w ho survived those tests without dabbing had to pluck a wooden spear from a holder as he rode past, stick it through a 1-in. hole in a 2-ft. diameter target, catch the spear as it came through the target, and place it in a second holder.

That was the tame stuff'.

Inside the oval is a 1.4-mile handling course with every kind of turn from highspeed to second-gear to decreasing radius to off-camber. One curve even has a big bump built into it that unloads, then slams the suspension while the bike is leaned over near the apex. Cutouts and traffic cones allow different routing, but the version open during the rally had 12 turns. The amazing thing is that anybody at the rally could bring their bike—be it a 50cc Kreidler or a CBX—and ride on the course with or without passenger. The waiting area was packed with bikes, hundreds of riders awaiting their turn.

There were several times set aside each day when rally-goers could be driven around the oval track in a fast car. sailing around the 57° banking at 90 mph. The car drivers didn’t even have to steer—the car would be flat and level on the straightaway one moment, then instantly be up on w hat seemed to be a vertical wall.

Selected, experienced riders at the rally were allowed to charge around the banking. following a Continental test rider. The front straightaway was still wet from sprinklers used in a wet-braking demonstration when I had a chance to ride a Honda CB900FZ on the oval. I didn't see how' anybody could go into the banking at 180 kph ( 1 12 mph) on wet tires and not crash, yet the test rider I was following did. But knowing it was possible and doing it were two different things.

And riding on the bank! To put the angle in perspective. Daytona is banked at 34°. The Contidrom makes Daytona look flat.

Even saying it’s 57° does it no justice. The angle is measured with a straight line from bank top to ground level. The banking itself is bow l-shaped and the effect is of riding inside a gigantic, concrete barrel. The left handlebar is pointed toward the ground, the suspension fully compressed under the force of 2g, the bike jumps around on small bumps. To stay near the painted line marking the top (fast) lane. must steer and make small corrections, but the bike follows the banking around with no need to start at the top. dive down on the middle and rise again at the end of the bank, which is how to ride shallower banked tracks.

As the sun slowly sets, one end of the track is in shadow, and riding the banking on that side is absolutely terrifying. On the wall, helmet and eyes in sunlight, motorcycle and wheels in shade, visibility nicht so gut (not so good). My big fear is that I'll ride over the lip of the bowl—which seems an arm’s length above the bike's gas tank — and fly off' into the forest below'. After five laps. I pull in.

The first two days of the rally. I wore Levis. T-shirt and leather jacket—and stood out in the crowd of leathepsuited riders. The third day I wore my racing leathers and blended right in. The only thing that drew attention was the scraped duct tape on my knees. Several riders asked—first in German, then in hesitant English—where they could get such “Kenny Roberts tape.”

The Contidrom was nearly empty the evening of the third day. the roads leading for the track clogged with riders going home to all parts of Germany. It was then, in front of empty grandstands, that 1 had chance to ride the Continental outriggerequipped test BMW on a surface of wet cobblestones. It's easy to crash on cobbles, and it’s fun when you can lowside. highside and flop back-and-forth while spinning like a top. all without injury. The wheels of the hydraulic outrigger system built by Continental technicians don't touch the ground until the motorcycle has “crashed.” It's then that the extra wheels turn certain death into great fun and hilarity. The feeling when the rear end passes the front and the bike highsides is impossible to describe. The best part is no “thud” afterwards . . .

I'm tooling down the autobahn and see a fantastic castle looming in the distance, so I pull oft'at the next exit (or Ausfahrt), head for the building and park on cobblestones. Finished in 1640 A.D. after 50 years of construction, the Schloss Arensburg is now a hotel and restaurant.

The house specialty is “Spargel mit Schinken.” But what the Ober (waiter) brings looks nothing like asparagus with ham. It is a plate of 12 pale-white, footlong. 3A-in. diameter shafts, each with a single, rounded tip. It may be the most suggestive piece of cuisine in the world.

The trouble with traveling in Europe is that although the countries are small and distances short, each country has its own language and currency. The traveller must change money often to have marks in Germany, guilders in Holland, francs in France, pounds in England. Every time you change, you lose. Take a check in pounds to an American bank and you get $1.80 for each pound. Buy pounds at a British port of entry and they cost you $2.14 each. Even though the exchange rates at banks inside countries—as opposed to on the borders—are better, the institution always comes out ahead. Money changing is big business, or maybe a big racket. And to cash American Express traveler’s checks, the banks take a commission as well.

It’s a case of house oddsthe banks never lose. That detective on TV never said anything about this.

The sun in northern Europe looks just like the sun in America. But it can't be the same sun. because although there's light and sunshine all around, it’s cold. Maybe standing still is okay, but jump on a bike in June and it's like California winter, no matter what the locals say about the warm weather. A heat wave in Cologne, it seems, is about 70°. It's better on occasion, and Holland was even hot for half a day. but in general it’s just not like a good-old-American summer.

The day plays by different rules, too. In Holland, the sun set at 10 p.m. and rose around 3 a.m.

Pull up to a gas station in Holland on a bike with German license plates and the attendant naturally speaks to you in German. “Achtundzwanzig, bitte.” 28 (guilders) please. But something in the tone, the look says that maybe the Dutch don't really like the Germans spilling into their country for vacations.

“Well.” a British friend said later w hen I told him the same story, “you must remember that every 25 or 30 years the Germans have gone on holiday in Western Europe with the Panzer tanks.”

His line got a big laugh in London, but somehow they seem to take it all more seriously in Venlo or Antwerp or Calais.

1 discovered an interesting German quirk while looking for my hotel the night before visiting the Continental motorcycle tire factory in Korbach. The hotel was in Arolsen, a small town in a scenic area of middle Germany, near Kassel. Following a road map, I pulled into Arolsen, walked into a tiny beer-hall/pool-room/hotel and started talking to the man behind the bar in English.

He didn't speak English. “Kein Zimmer frei” (no room free), had no reservation, had never heard of anybody named Ulrich.

“Esn't this the Schloss Hotel?” I asked in desperation.

Silence.

“Nein. Das ist nicht das Schloss Hotel.” More German, rapid-fire, then the man waves me outside and points down the road. I jump back on the bike, ride down the street, pass a sign indicating the Arolsen city limits. A mile or two later I enter another small town, with the sign “Arolsen.” Soon I was through it as well. Three more miles, another, larger, burg, with the same sign. “Arolsen.” This one had a Schloss Hotel, a mansion and tourist resort where everybody spoke English.

The next day. Manfred Kunz of Continental explained. To tidy up their topography, the Germans decided about five years ago that tiny little villages should all be called by the name of the nearest semilarge town. Thus, there may be three or four or five “Arolsens.” and only the locals know for sure which one is which or w hat it used to be called. It's enough to shake one’s faith in German engineering.

Everyone hears how expensive Europe is, and it's true that a dollar doesn’t buy what it used to. But on the nights when hotel reservations hadn't been made for me by the public relations man of a large company eager to show me the best (and most expensive), it wasn't that bad. Small hotels are everywhere. One night. I just turned off the autobahn onto a likelylooking secondary highway in Germany, wandering through the best scenery I'd seen, mountains with pines, picturesque towns nuzzling the hillsides and scattering across the valleys. A promising-looking “Gasthaus” appeared in Tübingen.

“Haben sie ein Zimmer frei, mit Bad?” (Have you a room free, with bath?—you must ask for a room w ith bath if you want a private bathroom and shower) I asked the motherly-looking lady bustling around the attached dining room, which was full of Germans drinking beer and eating. “Ja. Ja” she said, leading me upstairs into a spotless, new. large room complete with two beds, table, desk, chairs and crib. Breakfast was included and the bill was 34 marks, about SI7.00. A steak dinner in the restaurant cost 18 marks, about S9.00. A typical meal in a fast food place cost 10 marks, about S5.00. including two large bottles of “Limonade,” which is what Germans call soda pop regardless of flavor. That’s no more expensive than in the United States.

Manfred and Fritz, two young Germans who lived near Cologne, were waiting for the ferry boat from Dunkirk to Dover when I pulled up at 11 a.m. one rainy night. They were on their way to vacation in Ireland.

Manfred rode a new. German-market version SR500 Yamaha with a 27-horsepower engine. German insurance rates are set by horsepower, not displacement, and by buying the detuned model, Manfred could save about S100 a year in liability insurance premiums, paying about $400 instead of $500. Fritz had just bought a used R60/5 600cc BMW to replace the R75/6 his roommate had destroyed in an end-over-end crash. Fritz's BMW was cold blooded, refusing to take the throttle, spitting and sputtering until it warmed up. and he was worried sick that something was wrong. “Did you hear the explosions?” he said when the cylinders spit back into the carbs.

It took a lot to convince him that BMW's with slide-throttle carbs are like that, and everything was okay. But during a 2'2-hour ride on a boat carrying everything from pedestrians to freight trains, there’s plenty of time for talk.

I'd heard of English rain, and now I was in it. No wonder oily rainsuits. rubber boots, shaft drive and enclosed chain cases make a big hit with the English. This was serious rain. The 100 miles to London left me cold and soggy. Worse yet was finding Richmond. Surrey, w here friend and Cycle World contributor John Nutting lives. My map wasn't detailed enough. The gas stations I tried didn't have better maps for sale, and nobody I stopped on the street knew w here Surrey, a suburban area. was. It was incredible. Stop somebody on the street in Los Angeles and ask how to get Pasadena, and they’ll tell you.

But it's ÍK) wonder that London is confusing for even the residents. The city was largely built between 1850 and 1900. and there is no such thing as a straight road direct road. You'll be flying down motorway (freeway, interstate) and all of sudden there will be billboards diagramming a big traffic circle, called a roundabout. Everybody pitches it into a lefthander around the circle until they get their exit, which may be one of five or streets meeting there, and dive out. definitelv a case of bigger is best. The one time I thought I had the knack of it and was holding my own. I heard a loud “Honk!” coming from somewhere in the vicinity of my right leg. looked dow n and saw a white fender in near eontaet. all at mph. The driver was a determined, whitehaired old lady.

Gasoline in England is $3.00 a gallon. Spending the equivalent of $15 to fill up Yamaha is unnerving, and sporadic U.S.style gas lines were the talk of the day. The hovercraft has a hold for vehicles and an airline-style passenger cabin complete with attentive stewardesses. The hold has room for only two bikes, parked ofl'to the side in small niehes. When I lifted the Yamaha onto its centerstand, the left handlebar hooked a hull rib on the way up. I he bike teetered on one centerstand leg. then fell away from me w ith a resounding crash. Crewmen and amused passengers stared, motionless, as I struggled to lift the bike and gear without success until Steve White ran over from his BMW to help.

Hovercraft and cargo cross the English channel on a six-foot-tall bubble of air held captive bv a big, blaek skirt, kicking up a cloud of spray that obscures the view from the w indows. A jet-engine roar limits conversation. The ride is so bumpy that writing is difficult and the stewardesses hold onto seat backs as they prowl the aisles, but the 28-mile trip across the channel takes only 20 minutes on a fair day. White invited me to spend the night at his Paris apartment, and after being waved through customs, we were ofl.

continued on page 96

continued from page 75

White is a chemical engineer who moved to Paris with his French wife and young son to earn twice the salary he made doing the same work in London. During the week he writes operating manuals for ethylene plants being installed in the Middle East. This weekend he had ridden to Scotland to enter a rifle shooting match. Today he traveled 700 miles, including large stretches of country roads.

We parked our bikes in the courtyard o<* the old apartment building W hite lived in, near the center of the city. Fitting two people and gear into the tiny glass-andpolished-wood elevator that carried us tí the fifth floor was a major operation. We drank and talked motorcycles, nuclear protestors and ethylene economics until almost sunrise.

Paris and Reims were entertaining in a tourist sense, and the artwork alon$ French tollroads (with hefty tolls ranging up to $10.00) amusing. I wondered what manner of creative vandal had painted delicate bands of pastel hues across the face of an overpass on the first tollroad I ventured down during daylight. Imagine my surprise when, lining the banks beyond the overpass. I found artistically-arranged, widely-spaced concrete discs, six-feet across, painted the same hues. Another overpass with the bands of color, and beyond, concrete spheres on short stalks, again neatly arranged to enhance the scenery or improve the cultural setting, or whatever. Another overpass, this time diamond shapes in concrete along the freeway. Then squares. More discs. More spheres. For miles and miles, artwork on the roadside.

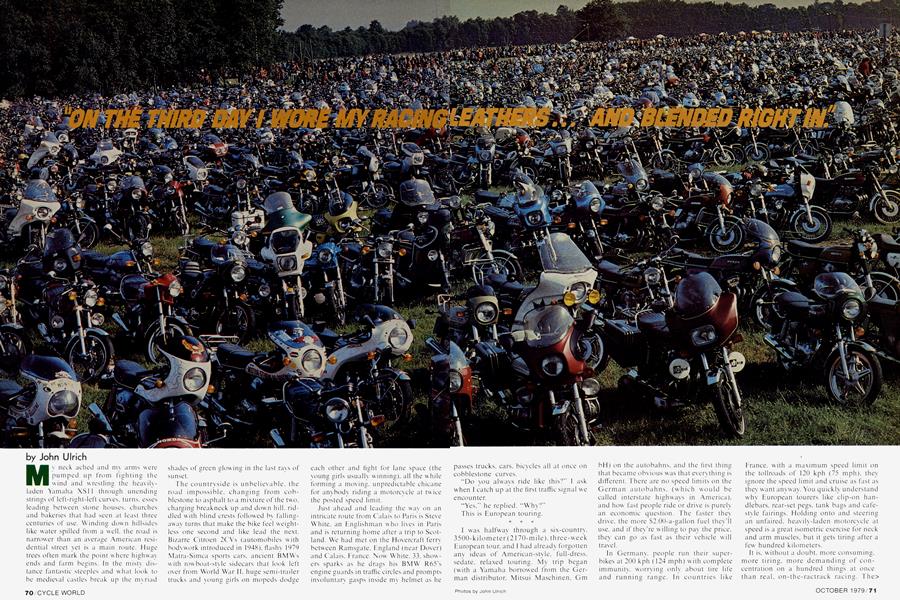

For excitement, nothing could top Assen. Holland, scene of the Dutch TT. a road racing Grand Prix. More than 130.000 people attended the race, lining th» entire racetrack maybe 50 deep. Twelve semi-trailers full of bottled beer were brought in to stock the beer tent. All of it was needed.

The motorcycle parking area was staggering. Have you ever seen 50.000 to 75.000 motorcycles parked in one place a^ one time? Name your choice, brand and size. It’s out there, somewhere, along with every accessory available on the continent. Racing aside, just seeing the bike park was worth the trip.

The crowds, gathered from all over Europe with Dutch and Germans predominating. filled surrounding camping areas, local hotels and the town of Assen. Townspeople welcomed the bikers . . . and their money. And when the race was over and the stream of cars, trucks and bikes clogging the highways for miles in every direction, townspeople and farm families from miles around lined roads and overpasses to watch the spectacle. They must not see anything like it for the rest of the year.

Munich is tremendous. But if you ask a German “Wo ist Munieh Zentrum?" (Where is the eenter of Munieh?) he'll look at you askance. In German it’s München.

Marienplatz (St. Mary’s Square) is a gathering point in the center of the city, the eastern approach to several streets turned into a pedestrian mall. Row after row of empty white chairs face the circa 1904 Gothic-style city hall as crowds of people hurry through the square.

Then, as the hour approaches, people stop and sit in the chairs, looking upward at the spires of the city hall. A bus pulls up two minutes before the hour, and tourists rush out to take positions in the square. Finally, the hour strikes, and when it does, the Glockenspiel on the city hall tower joins the crescendo of church bells echoing across the city. Figures depicting scenes from the 1568 wedding of Duke Wilhelm V appear parading into view on ornate balconies. When the wooden figures retreat and the music stops, the chairs in the square empty and people drift off to shop, eat. drink or listen to street musicians playing rock, folk, classical (with violin and cello). The musicians compete for coins thrown by passers by and some of them sing in terrible English to add a

touch of the exotic.

I covered the 800 kilometers (500 miles) from Munich to Löhne (to return the XSl l to Mitsui) in five sunny hours, including gas stops.

Make that five “almost” sunny hours.

Just 25 kilometers (15 miles) from my goal, a small clump of clouds appeared and poured out rain. The rivers of water from the heavens obscured road signs, pavement markings, everything. Even the Germans in cars slowed to 50 kph (30 mph). For 10 kilometers (six miles) the deluge continued. Then it ended suddenly, leaving behind warm and clear skies.

Finding my way through a maze of small German towns near Löhne was impossible. So I waved down the first motorcyclist I saw, a kid on a CBX with the mufflers gutted and steering damper added.

(Helmets are mandatory in Germany, yet he wore none. Seems that when they passed the law. the legislators didn't specify' any penalty, so violation is without consequence.)

He gave up trying to explain where Mitsui was in English and German, gestured. fired up the Honda and was off. riding on both sides of the street, getting sideways on sandy corners, dragging feet for a hundred yards after leaving each stop, his CBX’s empty mufflers emitting an unearthly howl. Ten minutes of mindless racing through narrow village streets and we were in front of Mitsui.

Then, with a wave, he was gone.

American. German. English. Motorcyclists are motorcyclists.

Everywhere, it’s the same.