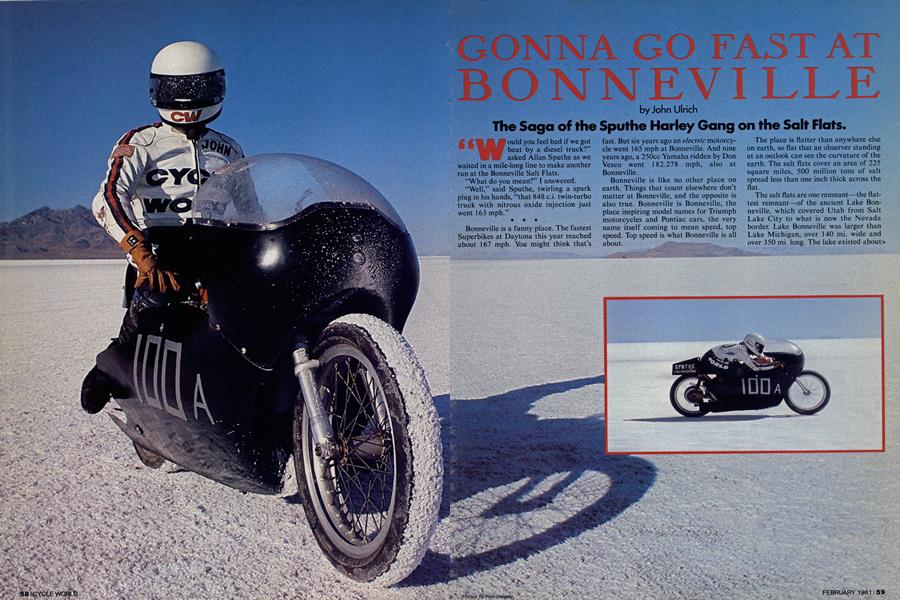

GONNA GO FAST AT BONNEVILLE

The Saga of the Sputhe Harley Gang on the Salt Flats.

john Ulrich

Would you feell bad if we got beat by a diesel truck?" asked Allan Sputhe as we waited in a mile-long line to make another run at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

"What do you mean?" I answered.

"Well," said Sputhe, twirling a spark plug in his hands, “that 848 c.i. twin-turbo truck with nitrous oxide injection just went 163 mph."

Bonneville is a funny place. The fastest Superbikes at Daytona this year reached about 167 mph. You might think that’s fast. But six years ago an electric motorcycle went 165 mph at Bonneville. And nine years ago, a 250cc Yamaha ridden by Don Vesco went 182.278 mph, also at Bonneville.

Bonneville is like no other place on earth. Things that count elsewhere don’t matter at Bonneville, and the opposite is also true. Bonneville is Bonneville, the place inspiring model names for Triumph motorcycles and Pontiac cars, the very name itself coming to mean speed, top speed. Top speed is what Bonneville is all about.

The place is flatter than anywhere else on earth, so flat that an observer standing at an outlook can see the curvature of the earth. The salt flats cover an area of 225 square miles, 500 million tons of salt spread less than one inch thick across the flat.

The salt flats are one remnant—the flattest remnant—of the ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered Utah from Salt Lake City to what is now the Nevada border. Lake Bonneville was larger than Lake Michigan, over 140 mi. wide and over 350 mi. long. The lake existed about> one million years ago, but most of the water slowly seeped out from the ring of mountains that held it, and as the water level dropped, the concentration of salts in the remaining water increased. Finally, Lake Bonneville shrunk to the Great Salt Lake near Salt Lake City, a body of water with 25 percent salt content, so much salt that you cannot sink if you go swimming in it.

Ron Hussey.

The salt flats, about 120 mi. west of Salt Lake City, are actually flooded much of the year. Instead of a normal water table, there is a brine table underneath the salt. When rains come, the flats flood with several feet of water. Near the end of summer, around August or September, the flats finally dry out until the rains resume in late October or early November and flood the flats for another year. When the flood comes, the salt dissolves into solution in the water, and when the flats dry out, the water evaporates and the brine table receeds underground, leaving a fresh deposit of salt about one inch thick on the surface.

Even when the flats are dry and runs are being made, the clay beneath the salt layer is moist and cool and the brine water level is less than one foot below the surface.

Like most everything else, Bonneville comes complete with political intrigues. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corp. has dug more than 50 mi. of ditches at the edges of the salt flats to drain off the underground brine. The brine is channeled into evaporating ponds, and the resultant salt—which contains potassium chloride—is milled into potash for fertilizer. Bonneville enthusiasts complain that the continued mining has reduced the thick-

ness of the salt and harmed the area in which the race course is laid out. The controversy doesn’t seem close to resolution.

Bonneville is a bleak, stark place. At 4300 ft. above sea level the air is thin, the sun bright. Sunburn is a problem, rays reflected off the salt intensifying exposure. Each year one week of competition is held under the auspices of the Southern California Timing Assn. (SCTA), and each year several hundred competitors, their crews and friends show up for speed week. Both cars and bikes run, more cars than bikes, for a total of 150 to 400 vehicles depending upon the year.

All those vehicles make for a long waiting line stretching back from the starting area, even on years with poor turnouts. The average entrant can make four or five passes down the course in a day, if he makes a pass and returns immediately to the line with no detours to the pit area for major repairs or adjustments.

At the end of the two-hour wait is a solitary pass down the 80 ft. wide course, dragged flat by a tractor and marked by black lines at each edge and up the middle. Timing lights are located at the 2, 2'A, and 3-mi. points in each direction on the course. Length of the actual course can vary from 1 1 mi. or more on a year when the salt is in good condition, down to 4 or 5 mi. when part of the salt flat is still flooded or part of the salt is too thin to drag into a good surface.

* * *

It rained a week before Speed Week 1980, and when we arrived, an ocean of brine covered the flats. Trucks and cars crammed the asphalt road leading into the flats, and people stood around where the pavement ended, peering at the waves. A

couple of writers from another motorcycle magazine, who had come to do a story on riding at Bonneville, were driving back toward the highway, and pulled up next to the Cycle World van.

“How’s it look?” 1 asked.

“Hopeless,” came the reply. “We’re going home.”

About an hour after the pair drove off, SCTA officiais led a procession of tow vehicles and racecars through two miles of the foot-deep salt water. At the other side of the brine lake the salt was dry enough to lay out 4.5 mi. of racecourse,-a pit area, and return roads.

We never saw the writers again.

* * *

Early mornings, when the air is cool and relatively dense, are reserved for record runs. To qualify for a record attempt, a vehicle must make a one-way pass faster than the existing record. The next morning, qualifiers line up and are waved off— one at a time—to make a run down the course. When the course is clear, another vehicle is waved off for its rendezvous with the timing lights.

But during record runs, instead of returning to the waiting line after a pass, the drivers and riders continue on to another staging area at the far end of the course. When all the record qualifiers are at the end of the course, return runs start. They’re identical to the down runs, except in the other direction. An average of the two runs determines speed for record purposes, in theory eliminating any advantage or disadvantage from winds or conditions at one end of the track or the other.

* * *

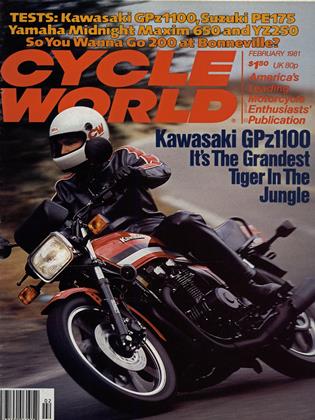

I had come to Bonneville with Sputhe and his Harley-Davidson Sportster, equipped, of course, with alloy cylinders and heads of Sputhe’s own design (featured in the July, 1980 issue of Cycle World). The plan was to set a record in the partially streamlined, modified engine, gasoline-fueled, 1300cc class, then switch to Roger Reed’s nitro-burning Sputhe engine and go over 200 mph. I liked the idea of going 200 mph, so much that I passed up a chance to go on a Honda press junket to Japan the same week as Bonneville.

Reed was with us to take care of his engine, which he normally uses in a hillclimber (!), the kind of monster with a mile-long swing arm and tire chains that Sputhe describes as “a real dirt bike, with lots of power.” The fourth member of our entourage was a Harley-Davidson mechanic named Joel (no kidding) Yamasaki, the sole employee of Sputhe Engineering.

We waited in line Monday, after fording the brine lake. I nodded off, still tired from driving all night to the flats, while Sputhe, Reed and Yamasaki worked on the bike in the back of the van. We were still in line when the sun dove behind the hills lining the salt flats, ending the day’s runs.

* * *

Tuesday morning, after record runs. The moment of truth was at hand. We were at the head of the line. Yamasaki fired up the bike and handed it over to me. The starter nodded his head and I let out the clutch. The motorcycle was geared for 175 mph at the 7000 rpm redline, so off the line you could almost count the explosions as the cylinders fired. Chug, chug, chug and away, faster and faster, building speed, too much throttle and the rear tire spins on the damp salt, shift into second, third, fourth.

A blizzard of salt flew up inside the fairing, thrown off the front tire, which had no fender. The flying salt coated the inside of the windshield, the outside of my helmet shield, bounced off my chin and up onto my lips, dashed to and fro in front of my eyes, settled on my arms. I concentrated on following the black line down the middle of the course and noted that the vibration sent shock waves up my spine from the thinly-padded seat. Just as I entered the timing lights at 2lA mi., the bike lost all power and I pulled in the clutch, fearing the worst.

I coasted off to the left side of the course, toward a spectator area and the timing stand, and an official ran out to meet me.

“What happened?” he asked.

“I think it blew up,” I answered.

“Did you lose any parts on the course?” he asked, staring at the bike.

I looked down at the engine, expecting to find parts hanging out of gaping holes, and suddenly realized that the carburetors . . . were gone. The intake manifolds, actually short pieces of straight steel looking to be about 3 in. across, protruded from each cylinder. Squinting against the glare I followed the carburetor cables down from the twist grip and found the 44mm Mikunis hanging by their cables, inside the fairing belly pan, underneath the engine.

I pointed, the official laughed and ran back to the tower as I pushed into the spectator area to wait.

At the far end of the course Sputhe, Reed and Yamasaki drove around aimlessly, trying to find me on the expanse of salt. They happened upon an official with a radio, who told them “He’s at the spectator area by the timing tower, and you motorcycle guys better get your act together— you’ve got work to do. Both carburetors fell off.”

* * *

For all the speed involved, riding at Bonneville appears to be amazingly safe. Speed Week began in 1949, but unorganized activity on the Salt Flats started before 1910. Thousands of records have been set on the salt, and as speeds have inched up, safety rules have been tightened up to match. Only one motorcyclist has been killed on the salt, in the early 1970s. In that case, the rider—without his helmet—was warming up his machine in the warm-up area, got going about 50 mph and crashed. He hit his head on the bike and died.

The most serious injury to a motorcyclist occurred in the 1950s when a man fell off his bike while wearing only a bathing suit and bathing cap—an early method of eliminating the wind resistance of flapping clothes. The near-nude rider lost a lot of skin, and what skin was left was imbedded with salt, but he survived.

Now full leather suits are required for regular motorcycles and fire-proof suits are required for enclosed streamliners. Safety is stressed throughout the rules.

One thing that the increased safety awareness and requirements hasn’t changed is the fact that Bonneville is one place where the amateur racer and dedicated enthusiast can win. Money doesn’t always guarantee success, as proven by the Honda Hawk streamliner disaster of 1972, when American Honda spent truckloads of money chasing the motorcycle land speed record, succeeding in setting one class record and earning the overall motorcycle top speed crash-destruction record when the Hawk flipped end over end at 280 mph.

It was proven again in 1979 when Rick Coatman, a young man from Greeley, Colorado, used his CBX to set two new records; and again in 1980 when Scott Spittier brought his GS1100 to the salt and raised Coatman’s 1300cc Production class record by 5 mph, turning 157.806 mph to Coatman’s 1979 record of 152.630 mph.

Spittler’s Suzuki was equipped with Vance and Hines Racing (VHR) 1198cc pistons with 13.8:1 c.r., Mega-Cycle camshafts, and a VHR 4-into-l exhaust system. The bike’s disconnected, stock muffler on the left side was safety-wired into position to give the bike the appearance of having the stock 4-into-2 exhaust system, and set off a rules controversy. Production class rules require that the exhaust system be “stock appearing” and CBX pilot Coatman and crew objected strenuously to Spittler’s bike. Officials, however, ruled in Spittler’s favor based upon their interpretation of the rulebook.

* * *

Working with a pair of Vise-Grips while we waited in line, Sputhe bent the edge of each intake manifold outward, into a flare. Slipping the rubber carburetor mount> hoses over the flare on each manifold and tightening down the hose clamps, he declared the carburetors secure. Two hours later I was back on the line, chugging away when the starter nodded. Before the lights the engine went on one cylinder, and I pulled off the course.

Puzzled when they reached me, Sputhe and crew poked and prodded the bike. I noticed that the XR750 fiberglass tank fitted to the bike rocked back and forth easily, and that the front-mounted righthand fuel petcock (which fed the front cylinder) could hit the rocker box. And that the petcock, which featured a sliding valve pushed up for off, was in fact closed. Engine vibration had moved the petcock within reach of the rocker box, which then pushed the petcock valve shut, starving the front cylinder.

More than a place of privateer success, Bonneville is a place of the unusual. Because there are so many classes and sub-

classes, there’s a place to run just about everything. So just about everything shows up in one form or another.

Like Dave Matson’s 1955 1735cc Vincent Black Shadow. Matson first brought his bike to Bonneville in 1959, then next returned in 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979 and now 1980. In 1979 Matson set a class record at 164.947 mph. In 1980 Matson and his Vincent went 178.246 in the 2000cc production-based, partially streamlined, gas-burning class and 173.432 mph in the 2000cc unlimited, partially-streamlined, gas-burning class. The bike also made a one-way pass of over 198 mph on nitro, but didn’t set a record.

The Harley-Davidsons on hand for Bonneville are always interesting, and the most interesting in 1980 was Tom Evans’ 107 c.i. monster built from a 74 c.i. engine and a lot of steel. Built to run nitro, Evans’ bike was supercharged (using a 1953 Paxton supercharger) with a fuel-injection system built out of $25 worth of surplus

aircraft equipment, including an $8 deicing pump.

Each cylinder of Evans’ bike was wrapped with a piece of cast iron sewer pipe sealed with rubber, fittings carrying water to and from a 5-gal. reservoir tank located underneath the seat. Water circulation was ensured by a batterypowered RV water pump.

The water tank, like the 3.12 gal. fuel tank and the seat (and the frame backbone for that matter) was made from 3/16-in. mild steel plate, a material selected for its easy availability and resistance to penetration by errant engine parts propelled by nitro.

Two years ago Evans went 179.2 mph on his monster. In 1980 the fastest he went was 158.401, after a run of 66.10 mph (due to fuel contaminated by dissolving fuel tank sealer) and a crash at about 40 mph when an attempt to tow-start the bike failed.

Yamasaki stuffed a wadded-up Cheetos bag, a beer can, and clumps of damp tissue paper underneath the front of the gas tank to hold the petcocks away from the front cylinder rocker box. Meanwhile, Sputhe wrapped duct tape around the frame front downtubes to block some of the salt spray off the front tire.

We had time for one final pass. This time, the bike ran all the way through the lights, reaching 157.48 mph measured between the 2 and 2lA mile lights, and slowed to a 155.89 mph average measured between the 2 and 3 mile lights.

Because the salt was wet and the course shortened by flooding, the famous Bonneville names with the fastest vehicles didn’t show up, or if they did show up, didn’t stick around to make runs. Don Vesco was still in his shop in Southern California working on his latest streamliner, powered by two turbocharged KZ1300 engines.

Turbochargers are the in thing at Bonneville, and less-well-known builders and riders made good use of them. Vern McPherson of Powroll sleeved down his CB400F to 350cc, fitted a small IHI turbo and set two records, the fastest being 127.823 mph.

Jim Ludiker built a turbocharged sohc Honda 750, which Barry Van Hook then rode to two 750cc class records, the fastest being 176.277 mph in the partiallystreamlined, turbocharged, gas-burning class.

Notes from Wednesday on the salt: Geared up by using two less teeth on rear sprocket, went through lights at 163.87 and 164.77 mph at 6800 rpm. Speeds don’t match gearing/rpm, and wheelspin is suspected since everyone else is complaining about the same problem.

Run two. Geared up with three less teeth on rear sprocket to reduce wheelspin. Bike ran through lights at 158.33 and

159.53 mph at 6000 rpm. Returned to line, discovered that the magneto had come loose, allowing timing to change at will.

Run three. Fixed magneto. Dropped another tooth off the rear sprocket. Went through the traps at 164.08 and 165.16 mph at 6500, the most rpm the engine would pull in fourth and third.

Run four. Cut two inches off the end of each exhaust pipe in effort to get more rpm. Bike revved to 7000 in third, pulled

163.54 and 163.49 mph in fourth at 6500. Lean jetting suspected.

Vance Breese pulled up Thursday morning with his Sputhe Sportster after driving all night.

His engine is in a rigid WR frame shielded by a full fairing. The gas tank is shaped like a U, the cutout serving as a place for Breese to put his chin in the search for the lowest possible profile—no helmet sticking up above the fairing bubble here.

On his first pass Breese’s bike loses a fuel line and spills gasoline all over, and he pulls off before reaching the lights. On his second pass, Breese reaches 169 mph, and declares that he is confident he can go the 175 mph necessary to set a class record.

Breese’s presence and instant success spurs on the Sputhe crew. They labor over the bike as we wait in line. I psych myself up. I’m gonna go fast. If mental will could send a bike over the mark, the Sputhe Sportster would reach 200 mph this morning.

Well, how about 152.59 through the quarter, then pulling off before the 3-mi. lights with the clutch obviously fried? The bike revved up to 7000 in fourth and I thought, “The wheelspin is bad this morning.” Then the rpm dropped suddenly to 6000 and smoke billowed up from the clutch.

The hunting, searching, wheelspin-like sensation I had felt all week must have been the slicks following shallow ruts made in the salt by the cars, because it couldn’t have been wheelspin. It was clutch spin. What else could it have been? With a new clutch, the bike went 167.34 and 167.81 at 6000 rpm.

And blew out every drop of oil, all over the inside of the fairing and bubble, and all over me.

When they arrived with the truck, Sputhe, Reed and Yamasaki were treated to the sight of my gray-green figure seated on Sputhe’s bike, arms outstretched, cross-shape, to keep the oil/salt stucco from running into my gloves.

Yamasaki jumped out of the van and peeled paper towels off a large roll, handing them to me as I troweled the salty slime off my leathers. Sputhe checked the oil tank—it was completely empty. Reed found a cracked oil return line and fixed it.

I pointed at the engine breather tube leading straight into an open-topped beer-can reservoir inside, the fairing, figuring it to be the culprit, and suggested that it be moved outside and behind the fairing.

Two hours later, on the course again, the bike revved to 6800 rpm in third and stayed there, with no sign of revving higher, so I slammed it into fourth and went 165.563 and 166.327, at 6000 rpm.

Again, all the oil landed on me. Yamasaki handed the towels, I trowled off the oily stucco, glared at the beer-can catch tank, and we gave up for the day.

“Any other motorcycle that had this much stuff happen to it would have fried, huh?” asked Sputhe, sitting close to the fire in our camp that night. “I guess that’s where Harleys get their reputation for being reliable. They’re tough little bastards. And when they do break, they’re easy to fix.”

“Right, Allan.”

“Of course,” he admitted, poking at the embers with a branch, “If it were any other motorcycle none of these things would have happened.”

Friday morning. The last day to qualify for a record, since Saturday was reserved for record runs alone.

Vance Breese fired up his bike and went 175 mph, faster than the existing class record of 174.513 mph set by John Haider on a Kawasaki in 1979. His speed qualified him for an official record run.

Yamasaki started Sputhe’s bike. I climbed on, hoping the air—as dense and as cool as we’d seen at Bonneville—would make the difference.

The bike went 165.289 and 165.425.

And blew out all the oil. Again.

Yamasaki jumped out of the truck with his roll of paper towels—almost used up by Thursday’s runs—and 1 smeared the oil-salt coating that now permeated my leathers.

“I’m going home, now,” I told Sputhe, Reed and Yamasaki.

They nodded. We loaded the truck, wished Breese well, and left.

On Saturday, Vance Breese and his Sputhe Sportster set a new MPSAG-1300 class record of 176.615.

On Monday, Allan Sputhe called me with some news.

“The problem was fuel starvation,” he said. “The engine was sucking the float bowls dry. And the oil leak was from a fitting on the bottom of the engine, which must have cracked when we were loading the bike into the truck Wednesday.

“I’m gonna fix the bike and take it out to the El Mirage dry lake, and since we never got time at Bonneville to try Reed’s nitro motor, maybe we can try it out there. You want to ride it?”

“Sure,” I said.

I have a short memory. And I really would like to go 200 mph. ES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue