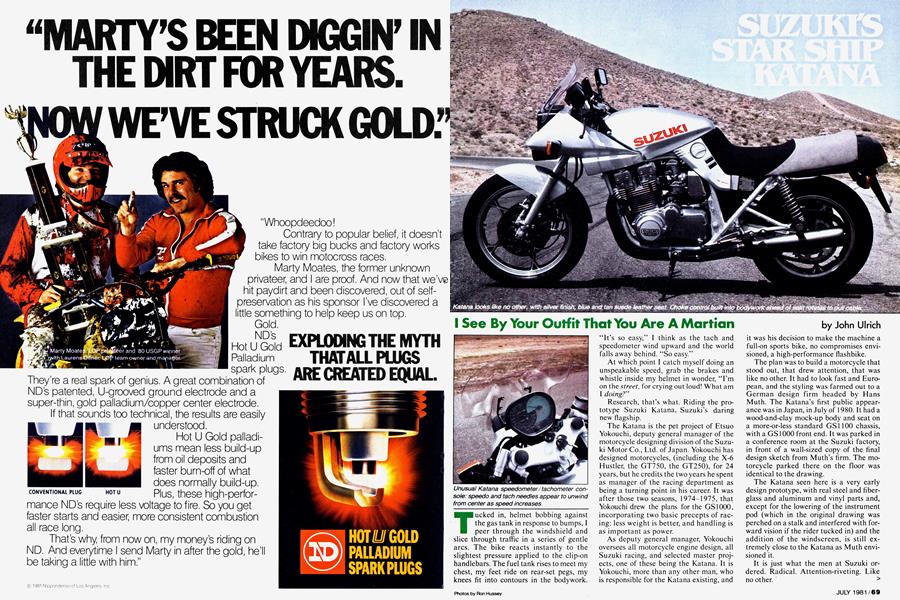

SUZUKI'S STAR SHIP KATANA

I See By Your Outfit That You Are A Martian

John Ulrich

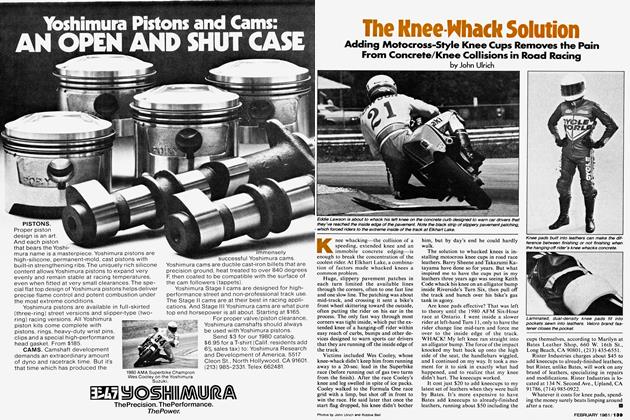

Tucked in, helmet bobbing against the gas tank in response to bumps, I peer through the windshield and slice through traffic in a series of gentle arcs. The bike reacts instantly to the slightest pressure applied to the clip-on handlebars. The fuel tank rises to meet my chest, my feet ride on rear-set pegs, my knees fit into contours in the bodywork.

“It’s so easy,” I think as the tach and speedometer wind upward and the world falls away behind. “So easy.”

At which point I catch myself doing an unspeakable speed, grab the brakes and whistle inside my helmet in wonder, “I’m on the street, for crying out loud! What am I doing?"

Research, that’s what. Riding the prototype Suzuki Katana, Suzuki’s daring new flagship.

The Katana is the pet project of Etsuo Yokouchi, deputy general manager of the motorcycle designing division of the Suzuki Motor Co., Ltd. of Japan. Yokouchi has designed motorcycles, (including the X-6 Hustler, the GT750, the GT250), for 24 years, but he credits the two years he spent as manager of the racing department as being a turning point in his career. It was after those two seasons, 1974-1975, that Yokouchi drew the plans for the GS1000, incorporating two basic precepts of racing: less weight is better, and handling is as important as power.

As deputy general manager, Yokouchi oversees all motorcycle engine design, all Suzuki racing, and selected master projects, one of these being the Katana. It is Yokouchi, more than any other man, who is responsible for the Katana existing, and

it was his decision to make the machine a full-on sports bike, no compromises envisioned, a high-performance flashbike.

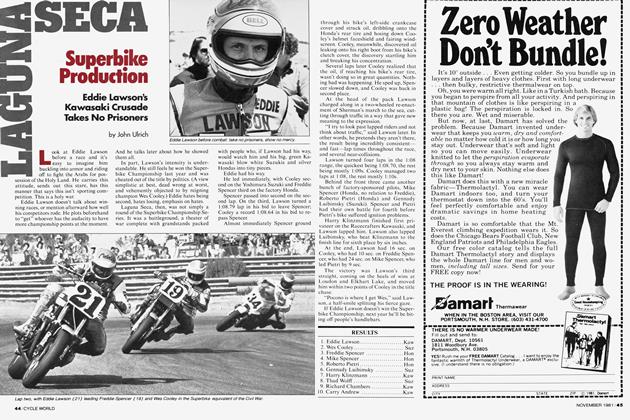

The plan was to build a motorcycle that stood out, that drew attention, that was like no other. It had to look fast and European, and the styling was farmed out to a German design firm headed by Hans Muth. The Katana’s first public appearance was in Japan, in July of 1980. It had a wood-and-clay mock-up body and seat on a more-or-less standard GS1100 chassis, with a GS1000 front end. It was parked in a conference room at the Suzuki factory, in front of a wall-sized copy of the final design sketch from Muth’s firm. The motorcycle parked there on the floor was identical to the drawing.

The Katana seen here is a very early design prototype, with real steel and fiberglass and aluminum and vinyl parts and, except for the lowering of the instrument pod (which in the original drawing was perched on a stalk and interfered with forward vision if the rider tucked in) and the addition of the windscreen, is still extremely close to the Katana as Muth envisioned it.

It is just what the men at Suzuki ordered. Radical. Attention-riveting. Like no other. >

Because this bike is a design prototype, anything could change before the machine reaches production, probably later this year. Which means that the specifications, performance, finish could all be different when the bike reaches dealers. What won’t change is the concept.

The initial Katana was to have a 1074cc GS1100 engine. The engine is still based on the GS1100, but bore has been reduced from 72mm to 69.4mm (stroke stays the same at 66mm) to bring displacement down to 998cc. That smaller displacement makes the four-valves-per-cylinder TSCC engine eligible for FIM World Championship endurance and F-l events, and may make it possible for the Katana to enter AMA Superbike races. However, the AMA is reluctant to allow clip-onequipped machines in the class and the controversy hasn’t been resolved.

This Katana is equipped to European specifications, with 32mm slide-throttle Mikuni carburetors and cams that open the intake valves at 35° BTDC and close them at 65° ABDC; the exhaust valves opening 63° BBDC and closing 25° ATDC.

When it comes to America, the Katana will have 34mm Mikuni CV carbs (like those on the GS1100 but with different jetting) and an intake cam that opens and closes the intake valves at 36.5° BTDC and 63.5° ABDC, the exhaust valve timing remaining unchanged. (For comparison, the GS1100 sold in America has the same exhaust valve timing but opens and closes the intake valves at 30° BTDC and 70° ABDC).

The engine vibrated excessively, because the smaller, lighter 69.4mm pistons have been used with a standard, balancedfor-72mm-pistons crankshaft. But it was still obvious that the bike made power, lots of it, from way down low up to about 8000 rpm, above which the engine was reluctant to rev.

The suspension is a combination of GS1100 shocks with much stiffer springs and GS1000 forks with spring-preload adjustment collars and an anti-dive system added. It could only be described as stiff, the kind of stiff you’d expect would be

required for a large German packing his large girlfriend over very rough European roads at full throttle. For a solo, normalsized rider the suspension was stiff to the point of being unyielding, especially in regards to small bumps.

But the Katana handled anyway, running true and stable at speed and changing directions with precision, although quick transitions from leaned-to-the-max left to leaned-to-the-max right meant hard work levering on those stubby bars. This is, after all, a street motorcycle with turn signals and horn and battery and steel gas tank, weighing 547 lb. with half a tank of gas, and those are, after all, real clip-ons just like the ones Wes Cooley uses, only cast of solid aluminum, instead of being fabricated from chrome-moly tubing.

The Katana doesn’t wobble or pitch or jump about. Rather, the tires start sliding as the bike’s speed around a bumpy, sweeping turn exceeds the ability of the tread rubber to grip without much help from the non-compliant suspension. And on the freeway, it might as well have a rigid chassis, the small blows of thousands of concrete expansion joints hammering the rider. All the while, the rider used to normal handlebars will suffer from aching wrists and back at legal speeds. But above 70 mph the wind reaching the rider around the screen takes some of the pressure off the arms and back, and at 90 mph everything reaches a wonderful equilibrium that makes 90 seem the ideal speed. At 120 and above, crouching low on the tank and peeking through the only distortion-free part of the screen—located straight ahead of the rider’s eyes when tucked in—stops any wind blast from buffeting the rider.

We hope the Katana anybody can buy will have suspension with a little more give. We also hope the Katana will not lose too much in the transition from design prototype to production-line machine. And we hope the Katana seen in the showroom will still look pretty much like that wallsized drawing pinned up in the conference room in Hamamatsu, which is to say, radical, attention-riveting, like no other.

Testing motorcycles for a magazine

means riding a lot of different bikes in rapid succession, sometimes as many as six new models a month. Doing that, it’s easy to get rather blasé about riding this bike or that.

Normally. On a normal bike.

Not on the Suzuki GS1000S Katana, a motorcycle that makes it easy to imagine that you’re aboard a Formula One machine, looking at motorists with disdain as you grab upshifts in rapid succession and disappear into the distance. The image that comes to mind is accelerating out of the Daytona chicane and hurtling around the banking.

This Katana is not a normal motorcycle. It elicits strong reactions and has a polarizing effect on any group of motorcyclists. Some people said that the Katana was the most beautiful motorcycle they had ever seen. And other people said it was the ugliest motorcycle on earth. This came from people we knew and people we didn’t know, people we saw every day and people we never saw before. But everywhere we went with the Katana, everytime we stopped, people gathered, stared, spoke.

The excitement and reactions didn’t cease when the Katana was in motion. If it was moving slowly enough to be caught, people in cars, trucks and on other bikes pulled alongside, gaped, waved, smiled, flashed copies of Cycle World, gave the thumbs-up salute or just dropped their jaws in amazement. No telling exactly what they thought, but it did get their attention, enough that they’d swerve across three lanes or slam on the brakes to get a closer look. Nothing I’ve ever ridden on the street drew that kind of attention, not the RE-5 rotary in 1974 nor the first Honda CBX in 1977.

When riding the Katana around and listening to people talk about it, I caught myself feeling defensive, thinking that I didn't care what anybody said or that some would never understand such a bike or that many thought it hideous.

There are plenty of nice, uniform motorcycles for them to buy.