WAR STORIES

ROADCRAFT Part IV

Right and wrong are most often determined by what our mother told us, or what the law lets us get away with and sometimes by our ability to figure out how to get what we want. Except motorcycle riding isn't like that. We learn what won't work when we try too much brake and discover a skidding tire doesn't work as well as a non-skidding tire. Or we can learn that more revs provide more power.

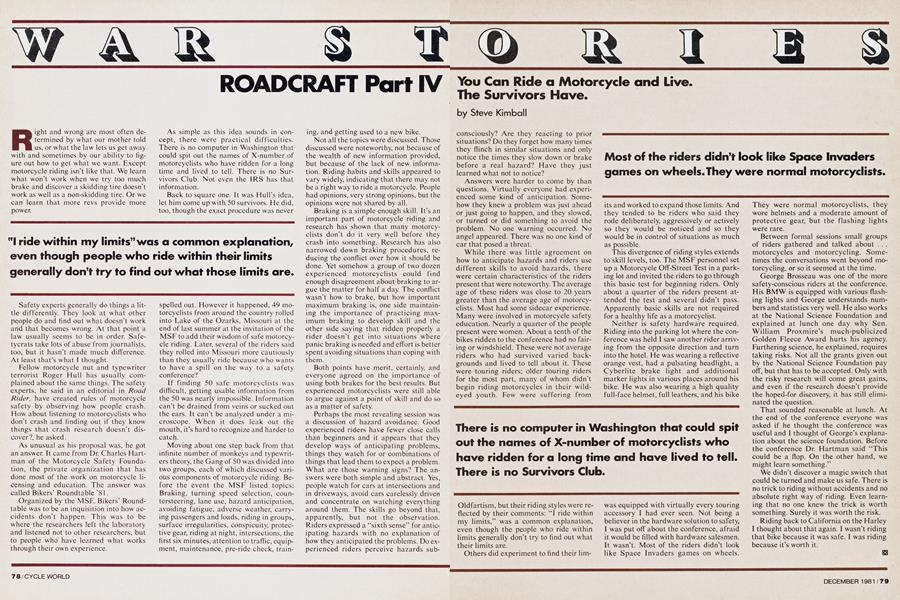

"I ride within my limits"was a common explanation, even though people who ride within their limits generally don't try to find out what those limits are.

Safety experts generally do things a little differently. They look at what other people do and find out what doesn’t work and that becomes wrong. At that point a law usually seems to be in order. Safetycrats take lots of abuse from journalists, too, but it hasn’t made much difference. At least that’s what I thought.

Fellow motorcycle nut and typewriter terrorist Roger Hull has usually complained about the same things. The safety experts, he said in an editorial in Road Rider, have created rules of motorcycle safety by observing how people crash. How about listening to motorcyclists who don’t crash and finding out if they know things that crash research doesn’t discover?, he asked.

As unusual as his proposal was, he got an answer. It came from Dr. Charles Hartman of the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, the private organization that has done most of the work on motorcycle licensing and education. The answer was called Bikers’ Roundtable ’81.

Organized by the MSF, Bikers’ Roundtable was to be an inquisition into how accidents don’t happen. This was to be where the researchers left the laboratory and listened not to other researchers, but to people who have learned what works through their own experience.

As simple as this idea sounds in concept, there were practical difficulties. There is no computer in Washington that could spit out the names of X-number of motorcyclists who have ridden for a long time and lived to tell. There is no Survivors Club. Not even the 1RS has that information.

Back to square one. It was Hull’s idea, let him come up with 50 survivors. He did, too, though the exact procedure was never

spelled out. However it happened, 49 motorcyclists from around the country rolled into Fake of the Ozarks, Missouri at the end of last summer at the invitation of the MSF to add their wisdom of safe motorcycle riding. Eater, several of the riders said they rolled into Missouri more cautiously than they usually ride because who wants to have a spill on the way to a safety conference?

If finding 50 safe motorcyclists was difficult, getting usable information from the 50 was nearly impossible. Information can’t be drained from veins or sucked out the ears. It can’t be analyzed under a microscope. When it does leak out the mouth, it’s hard to recognize and harder to catch.

Moving about one step back from that infinite number of monkeys and typewriters theory, the Gang of 50 was divided into two groups, each of which discussed various components of motorcycle riding. Before the event the MSF listed topics: Braking, turning speed selection, countersteering, lane use, hazard anticipation, avoiding fatigue, adverse weather, carrying passengers and loads, riding in groups, surface irregularities, conspicuity, protective gear, riding at night, intersections, the first six minutes, attention to traffic, equipment, maintenance, pre-ride check, training, and getting used to a new bike.

Not all the topics were discussed. Those discussed were noteworthy, not because of the wealth of new information provided, but because of the lack of new information. Riding habits and skills appeared to vary widely, indicating that there may not be a right way to ride a motorcycle. People had opinions, very strong opinions, but the opinions were not shared by all.

Braking is a simple enough skill. It’s an important part of motorcycle riding and research has shown that many motorcyclists don’t do it very well before they crash into something. Research has also narrowed down braking procedures, reducing the conflict over how it should be done. Yet somehow a group of two dozen experienced motorcyclists could find enough disagreement about braking to argue the matter for half a day. The conflict wasn’t how to brake, but how important maximum braking is, one side maintaining the importance of practicing maximum braking to develop skill and the other side saying that ridden properly a rider doesn’t get into situations where panic braking is needed and effort is better spent avoiding situations than coping with them.

Both points have merit, certainly, and everyone agreed on the importance of using both brakes for the best results. But experienced motorcyclists were still able to argue against a point of skill and do so as a matter of safety.

Perhaps the most revealing session was a discussion of hazard avoidance. Good experienced riders have fewer close calls than beginners and it appears that they develop ways of anticipating problems, things they watch for or combinations of things that lead them to expect a problem. What are those warning signs? The answers were both simple and abstract. Yes, people watch for cars at intersections and in driveways, avoid cars carelessly driven and concentrate on watching everything around them. The skills go beyond that, apparently, but not the observation. Riders expressed a “sixth sense” for anticipating hazards with no explanation of how they anticipated the problems. Do experienced riders perceive hazards subconsciously? Are they reacting to prior situations? Do they forget how many times they flinch in similar situations and only notice the times they slow down or brake before a real hazard? Have they just learned what not to notice?

You Can Ride a Motorcycle and Live. The Survivors Have.

Steve Kimball

Answers were harder to come by than questions. Virtually everyone had experienced some kind of anticipation. Somehow they knew a problem was just ahead or just going to happen, and they slowed, or turned or did something to avoid the problem. No one warning occurred. No angel appeared. There was no one kind of car that posed a threat.

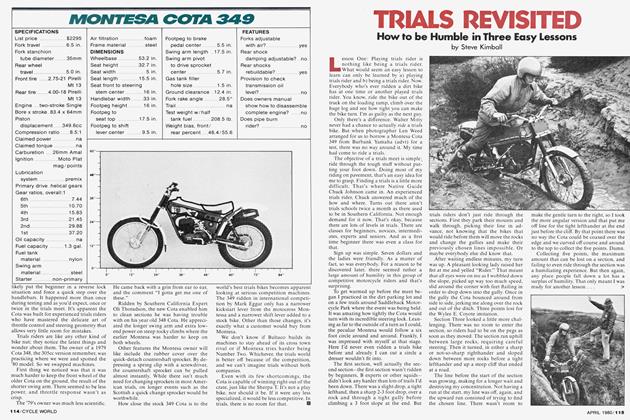

While there was little agreement on how to anticipate hazards and riders use different skills to avoid hazards, there were certain characteristics of the riders present that were noteworthy. The average age of these riders was close to 20 years greater than the average age of motorcyclists. Most had some sidecar experience. Many were involved in motorcycle safety education. Nearly a quarter of the people present were women. About a tenth of the bikes ridden to the conference had no fairing or windshield. These were not average riders who had survived varied backgrounds and lived to tell about it. These were touring riders; older touring riders for the most part, many of whom didn’t begin riding motorcycles in their wildeyed youth. Few were suffering from

There is no computer in Washington that could spit out the names of X-nUmber of motorcyclists who have ridden for a long time and have lived to tell. There is no Survivors Club.

Oldfartism, but their riding styles were reflected by their comments; “I ride within my limits,” was a common explanation, even though the people who ride within limits generally don’t try to find out what their limits are.

Others did experiment to find their lim-

Most of the riders didn't look like Space Invaders games on wheels.They were normal motorcyclists.

its and worked to expand those limits. And they tended to be riders who said they rode deliberately, aggressively or actively so they would be noticed and so they would be in control of situations as much as possible.

This divergence of riding styles extends to skill levels, too. The MSF personnel set up a Motorcycle Off-Street Test in a parking lot and invited the riders to go through this basic test for beginning riders. Only about a quarter of the riders present attended the test and several didn’t pass. Apparently basic skills are not required for a healthy life as a motorcyclist.

Neither is safety hardware required. Riding into the parking lot where the conference was held I saw another rider arriving from the opposite direction and turn into the hotel. He was wearing a reflective orange vest, had a pulsating headlight, a Cyberlite brake light and additional marker lights in various places around his bike. He was also wearing a high quality full-face helmet, full leathers, and his bike

was equipped with virtually every touring accessory I had ever seen. Not being a believer in the hardware solution to safety, I was put off about the conference, afraid it would be filled with hardware salesmen. It wasn’t. Most of the riders didn’t look like Space Invaders games on wheels. They were normal motorcyclists, they wore helmets and a moderate amount of protective gear, but the flashing lights were rare.

Between formal sessions small groups of riders gathered and talked about . . . motorcycles and motorcycling. Sometimes the conversations went beyond motorcycling, or so it seemed at the time.

George Brosseau was one of the more safety-conscious riders at the conference. His BMW is equipped with various flashing lights and George understands numbers and statistics very well. He also works at the National Science Foundation and explained at lunch one day why Sen. William Proxmire’s much-publicized Golden Fleece Award hurts his agency. Furthering science, he explained, requires taking risks. Not all the grants given out by the National Science Foundation pay off, but that has to be accepted. Only with the risky research will come great gains, and even if the research doesn’t provide the hoped-for discovery, it has still eliminated the question.

That sounded reasonable at lunch. At the end of the conference everyone was asked if he thought the conference was useful and I thought of George’s explanation about the science foundation. Before the conference Dr. Hartman said “This could be a flop. On the other hand, we might learn something.”

We didn’t discover a magic switch that could be turned and make us safe. There is no trick to riding without accidents and no absolute right way of riding. Even learning that no one knew the trick is worth something. Surely it was worth the risk.

Riding back to California on the Harley I thought about that again. I wasn’t riding that bike because it was safe. I was riding because it’s worth it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

December 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1981 -

Features

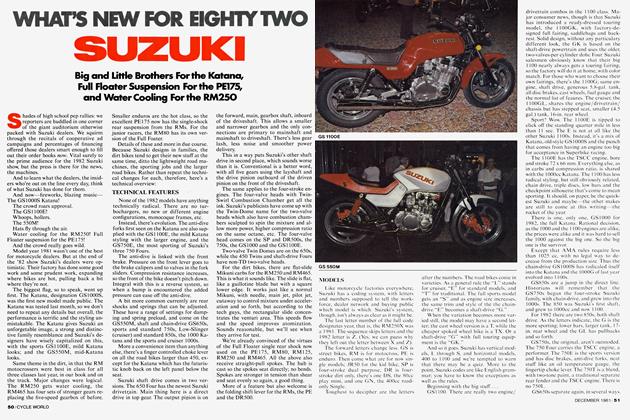

FeaturesWhat's New For Eighty Two Suzuki

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsBook Reviews

December 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Features

FeaturesA Guide To Orphan's Homes

December 1981 By Dee Winegardner