LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

A Mystic With A Love Of Speed

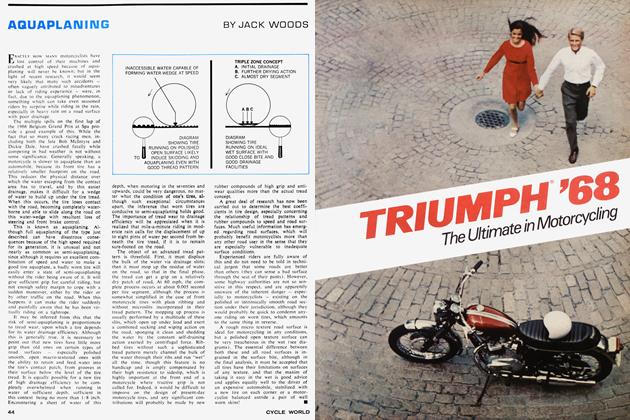

JACK WOODS

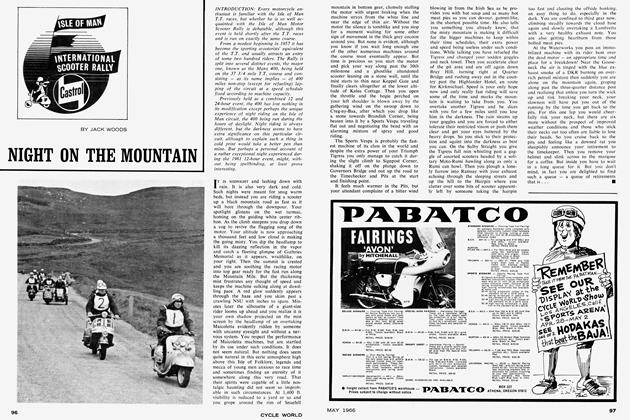

ALTHOUGH DOZENS OF books have been written about Lawrence of Arabia, the attention given to his love of motorcycling has been scanty. Indeed, many of his biographers scarcely mention the subject, which is a pity, as it provides an insight into the real nature of Lawrence's apparently enigmatic personality, so often the subject of analysis. The fact is, of course, that it takes a motorcyclist to understand a motorcyclist, and, as none of his biographers appear to have been motorcycling enthusiasts, their failure to attach much significance to Lawrence's hobby is both understandable and regrettable. Any attempt to explain what made Lawrence tick must suffer if this aspect of his nature is not taken into account, and to dismiss his motorcycling activity as just a passing fancy would be very wrong indeed.

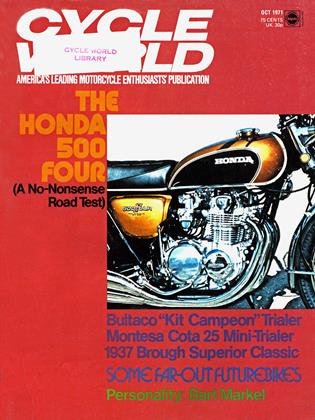

On the contrary, it was quite the reverse. Proof of this is provided by Lawrence himself; not only did he keep detailed and accurate records of his machines and journeys (he owned seven Brough Superiors and had an eighth on order before his death), but he also wrote one of the best essays on the joy of motorcycling ever printed. Phis essay, which originally appeared in the British Legion Journal for November 1933, also appeared in The Mint, which was Lawrence’s last work, published post-humously.

Lawrence’s first machine was a Brough SS80, probably a Mark II with a JAP engine. His last was a 1932 SSI00, which, incidentally, was discovered rusting away in a garage by Portsmouth enthusiast Les Perrin in 1963. Perrin bought the bike for a pound sterling (the bargain of a lifetime!) and, after a great deal of sweat and toil, restored the machine to its original glory.

The Mint was an account of Lawrence’s experience in the early days of the Royal Air Force, which he joined secretly, hiding his real identity under the pseudonym of Aircraftman Ross. He was soon discharged, however, but used his influence in high places to reenlist under another name, T.E. Shaw. Exactly why he chose to hide himself in the ranks of the then newly formed RAF has been the subject of much speculation. Even Lawrence’s own explanation is somewhat hazy, though his expressed intention of writing a book about his experiences in the ranks was real enough. The Mint was the outcome of his efforts, and here, from this book, is a facet of Lawrence which all motorcyclists will recognize as part of themselves—a liking for their own exhilarating company aboard a fast solo (which in this instance was a Brough Superior 1 000-cc V-'Pwin).

“The extravagance in which my surplus emotion expressed itself lay on the roads. So long as roads were tarred blue and straight, not hedged, and empty and dry, so long was I rich. Nightly I'd run up from the hangar upon the last stroke of work, spurring my tired feet to be nimble. The very movement refreshed them, after the day-long restraint of service.

“In five minutes my bed would be down, ready for the night; in four more, I was in breeches and puttees, pulling on my gauntlets as I walked over to my bike, which lived in a garage-hut opposite. Its tires never wanted air, its engine had a habit of starting at second kick - a good habit, for only by frantic plunging upon the starter pedal could my puny weight force the engine over the seven atmospheres of its compression. Boanerges’ first glad roar at being alive again nightly jarred the huts of Cadet College into life. ‘There he goes, the noisy beggar, ’someone would say enviously in every fight. It is part of an airman’s profession to be knowing with engines, and a thoroughbred engine is our undying satisfaction. The camp wore the virtue of my Brough like a fower in its cap. Tonight Tug and Dusty came to the step of our hut to see me off.

“ ‘Running down to Smoke, perhaps?’ jeered Dusty, hitting at my regular game of London and back for tea on Wednesday afternoons. Boa is a top-gear machine, as sweet as most singlecylinders are in middle gear. I chug most lordly past the guardroom and through the speed limit at no more than 16. Round the bend past the farm, and the way straightens. Now for it. The engine’s final development is 52 horsepower. A miracle, that all this docile strength waits behind the one tiny lever for the pleasure of my hand.

“Another bend: and I have the honor of one of England’s straightest and fastest roads. The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Soon / heard only the cry of the wind which my battering head split and fended aside. The cry rose with my speed to a shriek, while the air’s coldness streamed like two jets of iced water into my dissolving eyes. I screwed them into slits, and focused my sight 200 yd. ahead of me on the empty mosaic of the tar’s graveled undulations.

“Like arrows, the tiny fies pricked my cheeks, and sometimes a heavier body, some house fly or beetle, would crash into my face or lips like a spent bullet. A glance at the speedometer: 78. Boanerges is warming up.

“I pull the throttle right open, on the top of the slope, and we swoop fying across the dip, and up-down-up-down the switchback beyond, the weighty machine launching itself like a projectile with a whirr of wheels into the air at the take-off of each rise, to land lurchingly with such a snatch of the driving chain as jerks my spine like a rictus.

“Once we so fed across the evening light, with the mellow sun on my left, when a Bristol Fighter, from Whitewash Villas, our neighboring aerodrome, was banking sharply round. I checked speed an instant to wave: and the slipstream of my impetus snapped my arm and elbow astern, like a raised flail.

“The pilot pointed down the road towards Lincoln. I sat hard in the saddle, folded back my ears, and went away after him, like a dog after a hare. Quickly we drew abreast, as the impulse of his dive to my level exhausted itself.

“The next mile of the road was rough. 1 braced my feet into the rests, thrust with my arms, and clenched my knees on the tank till its rubber grips goggled under my thighs. Over the first pothole Boanerges screamed in surprise, its mudguard bottoming with a yawp on the tire. The plunges of the next 10 sec. would have distinguished a kangaroo dodging gunfire. I clung on, wedging my gloved hand in the throttle lever so that no bump should close it and spoil our speed.

“Then the bicycle wrenched sideways into three long ruts: it swayed dizzily, wagging its tail for 30 awful yd. Out came the clutch, the engine raced freely; Boa checked and straightened his head with a shake as Brough should.

“The bad ground was padded and on the new road our flight became birdlike. My head was blown out with air so that my ears had failed and we seemed to whirl soundlessly between the sun-gilt stubble fields. 1 dared, on a rise, to slow imperceptibly and glance sideways into the sky.

“There the Bif was, 200 yd. and more back. Play with the fellow? Why not? 1 slowed to 90: signaled with my hand for him to overtake. Slowed 10 more: sat up. Over he rattled. His passenger, a helmeted and goggled grin, hung out of the cockpit to pass me the ‘Upyer’ RAF randy greeting.

“They were hoping I was a flash in the pan, giving them best. Open went my throttle again. Boa crept level, 50 ft. below; held them; sailed ahead into the clean lonely country. An approaching car pulled nearly into its ditch at the sight of our race.

“The Bif was zooming among the trees and telegraph poles, with my scurrying spot only 8 yd. ahead. I gained though, gained steadily-was perhaps five miles an hour the faster. Down went my left hand to give the engine two dollops of oil, for fear that something was running hot; but an overhead JAP Twin, super tuned like this one, would carry on to the moon and back unfaltering.

“We drew near the settlement. A long mile before the first houses, I closed down and coasted to the crossroads by the hospital. Bif caught up, banked, climbed and turned for home, waving to me as long as he was in sight. Fourteen miles from camp, we are here, 15 min. since 1 left Tug and Dusty at the. hut door.

“1 let in the clutch again and eased Boanerges down the hill along the tram lines through the dirty street and uphill to the aloof cathedral, where it stood in frigid perfection above the cowering close. No message of mercy in Lincoln. Our God is a jealous God, and man’s best offering will fall disdainfully short of worthiness, in the sight of St. Hugh and his angels. Remigius, earthy old Remigius, looks with more charity on me and Boanerges. I stabled the steel magnificence of strength and speed at his west door and went in, to find the organist practicing something slow and rhythmical, like a multiplication table in notes, on the organ. The fretted, unsatisfying and unsatisfied lacework oj choir scream and spandrels drank in the main sound. Its surplus spilled thoughtfully into my ears. By then my belly had forgotten its lunch, my eyes smarted and streamed. Out again to sluice my head under the White Hart’s yard pump. A cup of real chocolate and a muffin at the teashop, and Boa and I took the Newark road for the last hour of daylight. He ambles at 45 and, when roaring his utmost, surpasses the hundred.

“A skittish motorbike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth, because of its logical extension of our faculties, and the hint, the provocation, to the success conferred by its honeyed, untiring smoothness. Because Boa loves me he gives me five more miles of speed than a stranger would get from him.

“At Nottingham I added sausages to the bacon which I’d bought at Lincoln: bacon so nicely sliced that each rasher meant a penny. The solid pannier bags behind the saddle took all this and at the next stop (a farm) took also a felt hammocked box of 15 eggs. Home by Sleaford, our squalid, purse-proud local village. Its butcher had six penn’orth of dripping ready for me. For months have I been making an evening round a’marketing, twice a week, riding a hundred miles for the joy of it and picking up the best food cheapest, over half the countryside.

“The fire is a cooking fire, red between the stove bars, all its flame and smoke burned off Half past eight. The other 10 fellows are yarning in a bluehaze of tobacco, two on the chairs, eight on the forms, waiting my return. After the clean night air their cigarette smoke gave me a coughing fit. Also, the speed of my last whirling miles by lamplight (the severest test of riding) had unsteadied my legs so that 1 staggered a little. ‘Wo-ups dearie, ’ chortled Dusty. It pleased them to imagine me wild on the road. To feed this flight vanity ¡gladden them with details of my scrap against the Bif

“ 'Bring any grub?' at length enquires Blackie, whose pocket is too low, always, for canteen. I knew there was something lacking. The excitement of the final dash and my oncoming weariness had chased from my memory the stuffed panniers of the Brough. Out into the night again steering aeross the black garage to the corner in which he is stabled by the fume of hot iron rising from his sturdy cylinders. Click, click, and the bags are detached; I pour out their contents before Dusty, the hut pantryman. Tug brings out the frying pan and has precedence. The fire is just right for it. A sizzle and a filling smell. I get ready my usual two slices of buttered toast. ”

This essay reveals the true Lawrence and the obvious pleasure he derived from motorcycling. In addition to this off-duty pastime, he also managed a one-man crusade to improve conditions in the (then) newly formed RAF, which he criticized from many aspects, ranging from the fitting of lavatory doors (recruits were denied even this basic privacy because the top brass of that cockeyed era believed that humiliation of any sort was good for discipline), to improvements in aircraft design. He was able to do this most effectively by using his influence in high places, especially via correspondence with the man who was responsible for the birth and growth of the Royal Air Force-Lord Trenchard.

As is obvious from the foregoing (not to mention his desert activities!), Lawrence was a man of many parts, possessing both the attributes of a poet and mystic along with the down-to-earth approach of a practical man. His practical aspect was no doubt responsible for his choice of motorcycle; the Brough Superior was regarded as the Rolls Royce of prewar British machines. He was lavish in his praise of these machines, which gave him a great deal of pleasure. The mileage he covered, according to his records, amounted to a total of 299,000 miles in 1 1 years, an average of 27,000 miles per year. That is quite some going, considering that English winters do not offer the best of motorcycling weather and often compel even the most hardy enthusiasts to stay indoors and forget the idea of motorcycling. Even considering the advantages of a modern machine with its superior roadholding and more comfortable suspension, a rider would be hard pressed to exceed Lawrence’s mileage on today’s crowded roads. Despite the somewhat cumbersome handling of the Brough, caused by its long wheelbase and inadequate rear suspension, the machine had the great advantage in the Thirties of being able to indulge in more full throttle gallops in a week than modern machines can risk in a year! In those golden days a Brough rider could put his hand change gear lever into the top notch and sit back while the effortless big Twin beneath him propelled him along for mile after mile through England’s green and pleasant (and almost deserted) countryside. Perhaps, though, the following few words written by Lawrence capture the scene of yesteryear’s motorcycling and, for that matter, the joy of all motorcycling both past and present . . .

“It’s usually my satisfaction to purr along gently about 60 mph, drinking in the air and general view. I lose detail even at such moderate speeds, but gain comprehension. When I open out a little more, as, for instance, across Salisbury plain at 80 or so, I feel the earth moulding herself under me. It is me piling up this hill, hollowing this valley, stretching out this level place. The earth almost comes alive, heaving and tossing on each side like a sea. It is the reward of speed. I could write you pages on the lustfulness of moving swiftly. ’’

These lines make it evident that Lawrence had more than a tinge of mysticism in his makeup, and possessed some insight into the motivation behind his love of speed. This is revealed in the following few lines of verse he wrote for his friend Lord Carlow: “In speed we hurl ourselves beyond the body. Our bodies cannot scale the heavens except in a fume of petrol. Bones. Blood. Flesh. All pressed inwards together. ”

He also told Lady Aston that “Nature would be merciful if she would end us at a climax and not in a decline.” It would seem from the foregoing that Lawrence had already glimpsed the circumstances of his own death in a motorcycle accident, although in some respects these circumstances have never been satisfactorily explained, and a series of legends has grown up about it. Some believe that Lawrence was not killed, but was involved in a fake accident for political purposes. Others feel sure that he was assassinated. The facts are not so romantic; they establish that Lawrence died after a road accident while trying to avoid a boy on a bicycle, and that any subsequent mystery about his death was caused by efforts to avoid publicity by the authorities. Perhaps a brief review of the last few months of Lawrence’s life will enable the reader to form his own opinion of the matter.

On Feb. 26, 1935, Aircraftman Shaw (Lawrence), who had been serving in Yorkshire, quit the RAF for good. He packed a saddlebag and rode off on a bicycle (not a motorcycle), heading for Dorset in the South of England, where he was renting a cottage at Clouds Hill. He was 47 years old and apparently feeling a little jaded, a mood which made the prospect of retirement appear even more pleasant. But retirement was not so sweet as he had imagined, and he grew restless at the aimless life he found himself leading in his cottage. He pottered about trying to give his life some meaning and purpose. He led a simple bachelor’s life, keeping chores to the minimum, using sleeping bags to avoid bedmaking and often eating straight from tins. His wants were few and he neither smoked nor drank. His early days at Clouds Hill were enlivened by reporters who came to see what Lawrence of Arabia was going to do next. Lawrence refused to see them, so they staked out a watch around his cottage, which led to a clash and one of them getting a black eye from Lawrence. This apparently upset him more than the reporter, although after the incident he was left alone to lead the eccentric life he had chosen for himself.

On the morning of the accident, Lawrence decided to visit Bovington to do some errands. Clouds Hill was about a mile and half from the few shops and post office that served Bovington Camp. The road between the cottage and the camp was then characterized by three dips at the Clouds Hill end. The dip furthest from Clouds Hill was the deepest, the second, less deep, and the third just abreast Lawrence’s cottage, scarcely perceptible. 1'he first two, however, were both deep enough to conceal approaching traffic from anyone at the bottom of them. The first dip was about 600 yd. from Clouds Hill, the second, 200 yd. nearer, and the third, about 100 yd. from a gate leading to the cottage itself. Lawrence usually rode to Bovington on his Brough Superior, which was noisy going through the gears but very quiet in top. A neighbor who lived close to Lawrence could always recognize his machine by the regularity of his gear changes as he entered the dips. On the day of the accident, he heard Lawrence accelerate off to Bovington at about 10:30 a.m., and later heard him returning in the distance. He heard him change down twice for the dips, then there was the usual silence which preceded his coasting into Clouds Hill. But he never arrived.

While Lawrence was in Bovington doing his errands (including sending a telegram and other business at the post office) Corporal Ernest Catchpole left Bovington camp and took his dog for a walk across the heath towards Clouds Hill. It was then 11:10 a.m. At 11:13 a.m., two delivery boys on bicycles left the camp and also rode towards Clouds Hill. Shortly afterwards, at approximately 11:20 a.m., Lawrence started the big Brough up and headed for home. A few minutes later, Corporal Catchpole heard the sound of a motorcyclist changing gear on approaching the first dip in the road. It was Lawrence, and as he entered the first dip, Catchpole saw emerging from the third dip— the one near Clouds Hill—a black car traveling in the opposite direction. Catchpole also saw the two boys on the crest of the road between the first and second dips. Then he saw Lawrence enter the middle dip and for a moment Lawrence, the car and the boys were all out of sight. The car emerged from the dip and went on towards Bovington. Almost simultaneously Catchpole heard the noise of a crash, and then a riderless motorcycle appeared, twisting over and over along the road. Catchpole ran to the scene and found Lawrence sprawled on the road, his face covered in blood. Just then an army truck came along. Catchpole stopped it and told the driver to take Lawrence and one of the boys, who was slightly injured, to Bovinglon Camp Hospital. Lawrence was unconscious on arrival, and after lingering in a coma for six days, he died.

(Continued on page 100)

Continued from page 70

The action of the authorities during those six days was probably responsible for much of the mystery and legend surrounding Lawrence’s death. I'he accident became an affair of State; all who served in the small camp hospital were reminded that they were subject to the Official Secrets Act. Newspaper editors were told that all information about the accident would be issued through the War Office. Four distinguished doctors, including two of the King’s physicians, were sent for, and there was a constant procession, day and night, of dispatch riders to and from the hospital. The King himself telephoned and asked for news, and the place was deluged with telegrams and other enquiries which were mostly rebuffed by the maximum security cordon thrown around the hospital. All this fostered a spate of rumors, the most widespread being that Lawrence was a secret agent with the plans for the defense of England in his head and/or had been killed by a foreign agent. Whatever else Lawrence carried in his head, there was one item for sure -a 9-in. fracture extending from the left side of the head backwards. Had Lawrence lived, he would have almost surely been disabled to some extent. As it was, his condition gradually grew worse, and he died on Sunday, May 19, just after 8 a.m.

Two days later an inquest was held at the hospital, and in many ways was unsatisfactory. Corporal Catchpole, as the principle witness, estimated Lawrence’s speed prior to the crash to be between 50 and 60 mph, although it is interesting to note that the Brough, badly damaged in the accident, was jammed in second gear, the top speed of which was 38 mph. The boys said that they had heard a motorcycle behind them so had moved into a single file, when Lawrence crashed without warning into the boy riding in the rear. Both denied having seen or heard a car of any sort. Catchpole was recalled and reexamined about the car but insisted he had not been mistaken. The coroner, unhappy about this conflicting evidence, told the jury that, although it was unsatisfactory, it did not necessarily mean the car was involved in the accident. The jury’s verdict was that Lawrence had died from injuries received accidentally, and the death certificate gave the cause of death as congestion of the lungs, heart failure following a fracture of the skull, and laceration of the brain sustained on being thrown from his motorcycle when colliding with a pedal cyclist. The vital question of how the accident happened was left unanswered.

A reinvestigation of the occurrence suggests that what happened was this: If was quite possible that a black car was on the road at the time. A witness said that a small black delivery van went past Clouds Hill at about the same time every day and, seen from where Catchpole was standing, could easily have been mistaken for a ear. The two hoys could have been mistaken about riding in single file upon hearing Lawrence’s machine approaching; they may have moved into single file when Lawrence was almost on top of them, and not, as they claimed, a minute or so beforehand. It seems certain that Lawrence came upon the black van on the crown of the middle dip, coming out of it as he was about to go into it. The road was narrow and they passed close to each other. Lawrence pulled in to the lefthand side of the road and,-as he did so, came suddenly on the two boys directly in front of him, with fatal results. Apart from happening to be passing at the time, the black van was not involved in the accident. But discussion about its existence has gone on for many years, along with other intriguing aspects of the matter, and no doubt will continue to do so, probably because romantic minds find it difficult to accept that an extraordinary man could presumably die in such an ordinary manner.

The funeral was held on the afternoon of the inquest and even though the public was requested not to attend, many well known figures were present in the village church at Moreton, including Winston Churchhill, Thomas Hardy, Lady Astor, Augustus John, Lionel Curtis and many others. G.B. Shaw and his wife, who were Lawrence’s close friends, were in Durban and unable to attend. The small cemetery where Lawrence lies is barely half full and his headstone is small and unimposing. Its inscription reads:

To the dear memory of T.E. Lawrence Fellow of All Souls College Oxford Born 16 August 1888 Died 19 May 1935 The hour is coming & now is When the dead shall hear The voice of the SON OF (;oD And they that hear Shall live

View Full Issue

View Full Issue