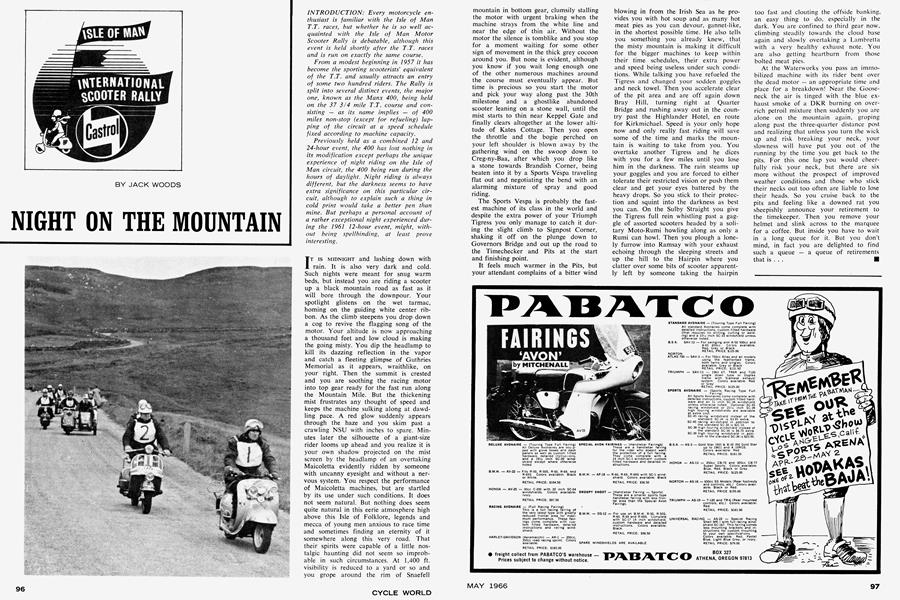

NIGHT ON THE MOUNTAIN

JACK WOODS

INTRODUCTION: Every motorcycle enthusiast is familiar with the Isle of Man T.T. races, but whether he is so well acquainted with the Isle of Man Motor Scooter Rally is debatable, although this event is held shortly after the T.T. races and is run on exactly the same course.

From a modest beginning in 1957 it has become the sporting scooterists' equivalent of the T.T. and usually attracts an entry of some two hundred riders. The Rally is split into several distinct events, the major one, known as the Manx 400, being held on the 37 3/4 mile T.T. course and consisting as its name implies of 400 miles non-stop (except for refueling) lapping of the circuit at a speed schedule fixed according to machine capacity.

Previously held as a combined 12 and 24-hour event, the 400 has lost nothing in its modification except perhaps the unique experience of night riding on the Isle of Man circuit, the 400 being run during the hours of daylight. Night riding is always different, but the darkness seems to have extra significance on this particular circuit, although to explain such a thing in cold print would take a better pen than mine. But perhaps a personal account of a rather exceptional night experienced during the 1961 12-hour event, might, without being spellbinding, at least prove interesting.

IT is MIDNIGHT and lashing down with rain. It is also very dark and cold. Such nights were meant for snug warm beds, but instead you are riding a scooter up a black mountain road as fast as it will bore through the downpour. Your spotlight glistens on the wet tarmac, homing on the guiding white center ribbon. As the climb steepens you drop down a cog to revive the flagging song of the motor. Your altitude is now approaching a thousand feet and low cloud is making the going misty. You dip the headlamp to kill its dazzing reflection in the vapor and catch a fleeting glimpse of Guthries Memorial as it appears, wraithlike, on your right. Then the summit is crested and you are soothing the racing motor into top gear ready for the fast run along the Mountain Mile. But the thickening mist frustrates any thought of speed and keeps the machine sulking along at dawdling pace. A red glow suddenly appears through the haze and you skim past a crawling NSU with inches to spare. Minutes later the silhouette of a giant-size rider looms up ahead and you realize it is your own shadow projected on the mist screen by the headlamp of an overtaking Maicoletta evidently ridden by someone with uncanny eyesight and without a nervous system. You respect the performance of Maicoletta machines, but are startled by its use under such conditions. It does not seem natural. But nothing does seem quite natural in this eerie atmosphere high above this Isle of Folklore, legends and mecca of young men anxious to race time and sometimes finding an eternity of it somewhere along this very road. That their spirits were capable of a little nostalgic haunting did not seem so improbable in such circumstances. At 1,400 ft. visibility is reduced to a yard or so and you grope around the rim of Snaefell mountain in bottom gear, clumsily stalling the motor with urgent braking when the machine strays from the white line and near the edge of thin air. Without the motor the silence is tomblike and you stop for a moment waiting for some other sign of movement in the thick grey cocoon around you. But none is evident, although you know if you wait long enough one of the other numerous machines around the course must eventually appear. But time is precious so you start the motor and pick your way along past the 30th milestone and a ghostlike abandoned scooter leaning on a stone wall, until the mist starts to thin near Keppel Gate and finally clears altogether at the lower altitude of Kates Cottage. Then you open the throttle and the bogie perched on your left shoulder is blown away by the gathering wind on the swoop down to Creg-ny-Baa, after which you drop like a stone towards Brandish Corner, being beaten into it by a Sports Vespa traveling flat out and negotiating the bend with an alarming mixture of spray and good riding.

The Sports Vespa is probably the fastest machine of its class in the world and despite the extra power of your Triumph Tigress you only manage to catch it during the slight climb to Signpost Corner, shaking it off on the plunge down to Governors Bridge and out up the road to the Timechecker and Pits at the start and finishing point.

It feels much warmer in the Pits, but your attendant complains of a bitter wind blowing in from the Irish Sea as he provides you with hot soup and as many hot meat pies as you can devour, gannet-like, in the shortest possible time. He also tells you something you already knew, that the misty mountain is making it difficult for the bigger machines to keep within their time schedules, their extra power and speed being useless under such conditions. While talking you have refueled the Tigress and changed your sodden goggles and neck towel. Then you accelerate clear of the pit area and are off again down Bray Hill, turning right at Quarter Bridge and rushing away out in the country past the Highlander Hotel, en route for Kirkmichael. Speed is your only hope now and only really fast riding will save some of the time and marks the mountain is waiting to take from you. You overtake another Tigress and he dices with you for a few miles until you lose him in the darkness. The rain steams up your goggles and you are forced to either tolerate their restricted vision or push them clear and get your eyes battered by the heavy drops. So you stick to their protection and squint into the darkness as best you can. On the Sulby Straight you give the Tigress full rein whistling past a gaggle of assorted scooters headed by a solitary Moto-Rumi howling along as only a Rumi can howl. Then you plough a lonely furrow into Ramsay with your exhaust echoing through the sleeping streets and up the hill to the Hairpin where you clatter over some bits of scooter apparently left by someone taking the hairpin too fast and clouting the offside banking, an easy thing to do. especially in the dark. You are confined to third gear now, climbing steadily towards the cloud base again and slowly overtaking a Lambretta with a very healthy exhaust note. You are also getting heartburn from those bolted meat pies.

At the Waterworks you pass an immobilized machine with its rider bent over the dead motor — an appropriate time and place for a breakdown! Near the Gooseneck the air is tinged with the blue exhaust smoke of a DKR burning on overrich petroil mixture then suddenly you are alone on the mountain again, groping along past the three-quarter distance post and realizing that unless you turn the wick up and risk breaking your neck, your slowness will have put you out of the running by the time you get back to the pits. For this one lap you would cheerfully risk your neck, but there are six more without the prospect of improved weather conditions and those who stick their necks out too often are liable to lose their heads. So you cruise back to the pits and feeling like a downed rat you sheepishly announce your retirement to the timekeeper. Then you remove your helmet and slink across to the marquee for a coffee. But inside you have to wait in a long queue for it. But you don't mind, in fact you are delighted to find such a queue a queue of retirements that is . . .