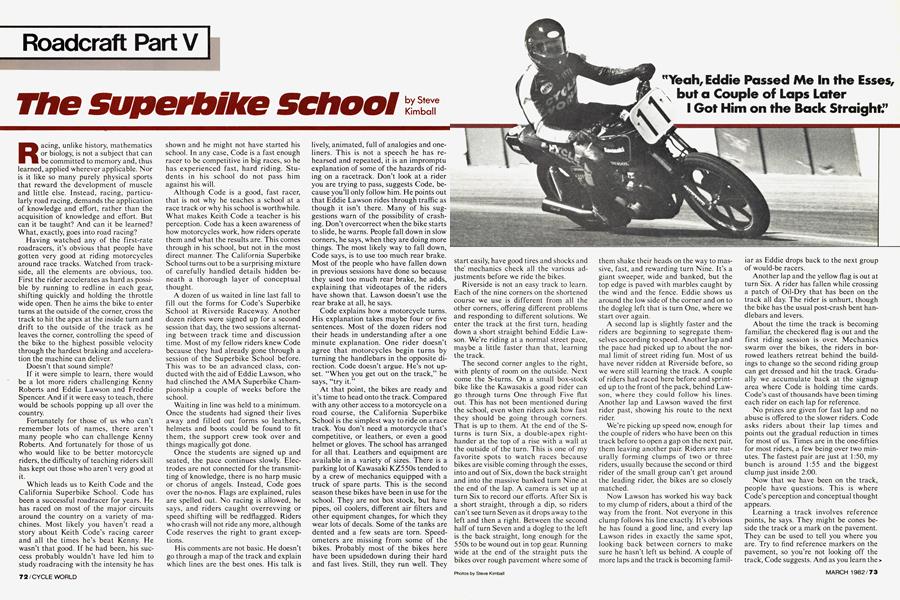

The Superbike School

Roadcraft Part V

Steve Kimball

Racing, unlike history, mathematics or biology, is not a subject that can be committed to memory and, thus learned, applied wherever applicable. Nor is it like so many purely physical sports that reward the development of muscle and little else. Instead, racing, particularly road racing, demands the application of knowledge and effort, rather than the acquisition of knowledge and effort. But can it be taught? And can it be learned? What, exactly, goes into road racing?

Having watched any of the first-rate roadracers, it’s obvious that people have gotten very good at riding motorcycles around race tracks. Watched from trackside, all the elements are obvious, too. First the rider accelerates as hard as possible by running to redline in each gear, shifting quickly and holding the throttle wide open. Then he aims the bike to enter turns at the outside of the corner, cross the track to hit the apex at the inside turn and drift to the outside of the track as he leaves the corner, controlling the speed of the bike to the highest possible velocity through the hardest braking and acceleration the machine can deliver.

Doesn’t that sound simple?

If it were simple to learn, there would be a lot more riders challenging Kenny Roberts and Eddie Lawson and Freddie Spencer. And if it were easy to teach, there would be schools popping up all over the country.

Fortunately for those of us who can’t remember lots of names, there aren’t many people who can challenge Kenny Roberts. And fortunately for those of us who would like to be better motorcycle riders, the difficulty of teaching riders skill has kept out those who aren’t very good at it.

Which leads us to Keith Code and the California Superbike School. Code has been a successful roadracer for years. He has raced on most of the major circuits around the country on a variety of machines. Most likely you haven’t read a story about Keith Code’s racing career and all the times he’s beat Kenny. He wasn’t that good. If he had been, his success probably wouldn’t have led him to study roadracing with the intensity he has shown and he might not have started his school. In any case, Code is a fast enough racer to be competitive in big races, so he has experienced fast, hard riding. Students in his school do not pass him against his will.

Although Code is a good, fast racer, that is not why he teaches a school at a race track or why his school is worthwhile. What makes Keith Code a teacher is his perception. Code has a keen awareness of how motorcycles work, how riders operate them and what the results are. This comes through in his school, but not in the most direct manner. The California Superbike School turns out to be a surprising mixture of carefully handled details hidden beneath a thorough layer of conceptual thought.

A dozen of us waited in line last fall to fill out the forms for Code’s Superbike School at Riverside Raceway. Another dozen riders were signed up for a second session that day, the two sessions alternating between track time and discussion time. Most of my fellow riders knew Code because they had already gone through a session of the Superbike School before. This was to be an advanced class, conducted with the aid of Eddie Lawson, who had clinched the AMA Superbike Championship a couple of weeks before the school.

Waiting in line was held to a minimum. Once the students had signed their lives away and filled out forms so leathers, helmets and boots could be found to fit them, the support crew took over and things magically got done.

Once the students are signed up and seated, the pace continues slowly. Electrodes are not connected for the transmitting of knowledge, there is no harp music or chorus of angels. Instead, Code goes over the no-nos. Flags are explained, rules are spelled out. No racing is allowed, he says, and riders caught overrevving or speed shifting will be redflagged. Riders who crash will not ride any more, although Code reserves the right to grant exceptions.

His comments are not basic. He doesn’t go through a map of the track and explain which lines are the best ones. His talk is lively, animated, full of analogies and oneliners. This is not a speech he has rehearsed and repeated, it is an impromptu explanation of some of the hazards of riding on a racetrack. Don’t look at a rider you are trying to pass, suggests Code, because you’ll only follow him. He points out that Eddie Lawson rides through traffic as though it isn’t there. Many of his suggestions warn of the possibility of crashing. Don’t overcorrect when the bike starts to slide, he warns. People fall down in slow corners, he says, when they are doing more things. The most likely way to fall down, Code says, is to use too much rear brake. Most of the people who have fallen down in previous sessions have done so because they used too much rear brake, he adds, explaining that videotapes of the riders have shown that. Lawson doesn’t use the rear brake at all, he says.

Code explains how a motorcycle turns. His explanation takes maybe four or five sentences. Most of the dozen riders nod their heads in understanding after a one minute explanation. One rider doesn’t agree that motorcycles begin turns by turning the handlebars in the opposite direction. Code doesn’t argue. He’s not upset. “When you get out on the track,” he says, “try it.”

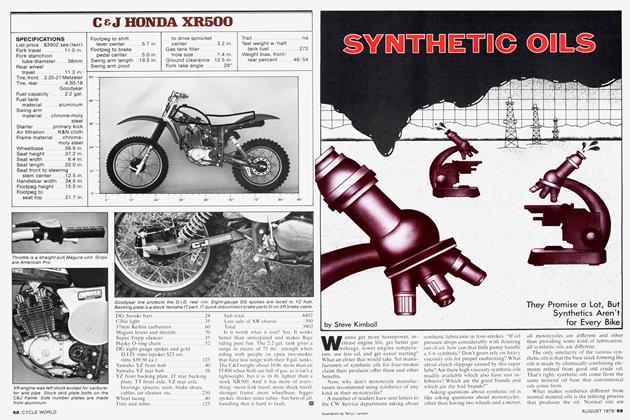

At that point, the bikes are ready and it’s time to head onto the track. Compared with any other access to a motorcycle on a road course, the California Superbike School is the simplest way to ride on a race track. You don’t need a motorcycle that’s competitive, or leathers, or even a good helmet or gloves. The school has arranged for all that. Leathers and equipment are available in a variety of sizes. There is a parking lot of Kawasaki KZ550s tended to by a crew of mechanics equipped with a truck of spare parts. This is the second season these bikes have been in use for the school. They are not box stock, but have pipes, oil coolers, different air filters and other equipment changes, for which they wear lots of decals. Some of the tanks are dented and a few seats are torn. Speedometers are missing from some of the bikes. Probably most of the bikes here have been upsidedown during their hard and fast lives. Still, they run well. They start easily, have good tires and shocks and the mechanics check all the various adjustments before we ride the bikes.

"Yeah, Eddie Passed Me In the Esses, but a Couple of Laps Later I Got Him on the Back Straight.”

Riverside is not an easy track to learn. Each of the nine corners on the shortened course we use is different from all the other corners, offering different problems and responding to different solutions. We enter the track at the first turn, heading down a short straight behind Eddie Lawson. We’re riding at a normal street pace, maybe a little faster than that, learning the track.

The second corner angles to the right, with plenty of room on the outside. Next come the S-turns. On a small box-stock bike like the Kawasakis a good rider can go through turns One through Five flat out. This has not been mentioned during the school, even when riders ask how fast they should be going through corners. That is up to them. At the end of the Sturns is turn Six, a double-apex righthander at the top of a rise with a wall at the outside of the turn. This is one of my favorite spots to watch races because bikes are visible coming through the esses, into and out of Six, down the back straight and into the massive banked turn Nine at the end of the lap. A camera is set up at turn Six to record our efforts. After Six is a short straight, through a dip, so riders can’t see turn Seven as it drops away to the left and then a right. Between the second half of turn Seven and a dogleg to the left is the back straight, long enough for the 550s to be wound out in top gear. Running wide at the end of the straight puts the bikes over rough pavement where some of them shake their heads on the way to massive, fast, and rewarding turn Nine. It’s a giant sweeper, wide and banked, but the top edge is paved with marbles caught by the wind and the fence. Eddie shows us around the low side of the corner and on to the dogleg left that is turn One, where we start over again.

A second lap is slightly faster and the riders are beginning to segregate themselves according to speed. Another lap and the pace had picked up to about the normal limit of street riding fun. Most of us have never ridden at Riverside before, so we were still learning the track. A couple of riders had raced here before and sprinted up to the front of the pack, behind Lawson, where they could follow his lines. Another lap and Lawson waved the first rider past, showing his route to the next rider.

We’re picking up speed now, enough for the couple of riders who have been on this track before to open a gap on the next pair, them leaving another pair. Riders are naturally forming clumps of two or three riders, usually because the second or third rider of the small group can’t get around the leading rider, the bikes are so closely matched.

Now Lawson has worked his way back to my clump of riders, about a third of the way from the front. Not everyone in this clump follows his line exactly. It’s obvious he has found a good line, and every lap Lawson rides in exactly the same spot, looking back between corners to make sure he hasn’t left us behind. A couple of more laps and the track is becoming familiar as Eddie drops back to the next group of would-be racers.

Another lap and the yellow flag is out at turn Six. A rider has fallen while crossing a patch of Oil-Dry that has been on the track all day. The rider is unhurt, though the bike has the usual post-crash bent handlebars and levers.

About the time the track is becoming familiar, the checkered flag is out and the first riding session is over. Mechanics swarm over the bikes, the riders in borrowed leathers retreat behind the buildings to change so the second riding group can get dressed and hit the track. Gradually we accumulate back at the signup area where Code is holding time cards. Code’s cast of thousands have been timing each rider on each lap for reference.

No prizes are given for fast lap and no abuse is offered to the slower riders. Code asks riders about their lap times and points out the gradual reduction in times for most of us. Times are in the one-fifties for most riders, a few being over two minutes. The fastest pair are just at 1:50, my bunch is around 1:55 and the biggest clump just inside 2:00.

Now that we have been on the track, people have questions. This is where Code’s perception and conceptual thought appears.

Learning a track involves reference points, he says. They might be cones beside the track or a mark on the pavement. They can be used to tell you where you are. Try to find reference markers on the pavement, so you’re not looking off the track, Code suggests. And as you learn the> track, he says, try to reduce the number of reference points and simplify the decisions that are required.

Specific questions are asked. How fast can the bikes be ridden through turn Two? How fast can we go in turn Nine? What’s the best line through turn Six?

Code doesn’t tell people how fast they can go through corners, though other riders volunteered that it’s possible to go flat out through Two and we were informed that not even Eddie goes through Nine wide open. Turn Six became an example of how race track designers make life difficult for racers and what we could do about it. Our objective, we were informed, was to come out of the corner as fast as possible. How was the corner banked, asked Code? After riding through it a dozen times most of us didn’t know how it was banked. Figuring out a proper line, said Code, is best done in reverse. Begin with where you want to exit and figure out how to get there.

In any case, slow corners are not places to pick up time, Code says. The key to picking up speed is in the fast part of the track. At Riverside that meant going faster in turn Nine and not backing off the throttle for turn Two. I knew there were wasted seconds being spent in these two spots, but what was so easy to theorize is hard to do on the track when you are running somewhere over 100 mph and there’s a wall at the outside of the corner.

It’s important to build a sense of speed, continued Code, explaining that sounds and feelings coming through the bike should be telling us how fast the bike is going and how much traction is available. Using the engine for braking, or overrevving it, hurts the sense of traction, Code says.

Armed with keys to unlock the track’s mysteries, the class has a brief lunch and heads for the bikes that have just returned from the track. Another rider has crashed, again unhurt. The other section was led around by Richard Lovell and they have been about 10 sec. a lap slower than the advanced class.

Again, Lawson leads us onto the track like mama duck and 12 baby ducks. This time the two warm-up laps seem slower, though they are not. Everyone is going into and through turn Six more smoothly this time, with fewer riders trying to turn it into two turns.

As Eddie speeds up and the pack spreads out, the riding begins to feel like racing. For the first time I’m riding a little hard, trying to go faster. The fastest pair are again at the front of the pack. Two other riders are ahead of me, going just as fast as I want to go most places and only holding me up a little, not enough for me to pass. Gradually the three of us speed up, lap after lap. The two ahead of me change places on turn Nine.

Trying to find reference points, I start working on my two problems, turns Two and Nine. Noting where I’m backing off and how much room is left over, it becomes easier to go in deeper through each of these fast corners. Then another rider, not part of our Gang of Three, comes past going in to the blind turn Seven. He glides through the lefthand first part of the turn and slides off the track leaving the righthand second part of the turn. A cloud of dust and a hearty Hi-Ho Silver. He is unhurt.

Finally I go wide going into turn Nine, come out low and pass one of my unofficial partners. The next one is still going slower through the S-turns than I want to go. Turn Nine comes up again and the next rider I get going into the corner. This time I’m pumped up and make it through turn Two without backing off as I hear a bike coming close behind me. He’s not going to get back around, I think to myself, but there comes the other bike, past in the esses. When I see that it’s Lawson coming around, I breathe easier. For two laps he leads the Gang of Three around the course. Without looking back I can feel I’m now clear of the other two, following Eddie around, watching him make the same lines, close on One, late on Two, early on Three, Four and wide on Five, cutting Six too close, going wide into Seven and accelerating between the first half and second half of it, cutting across the back straight to hit the dogleg on the side and around Nine close and fast.

Half a lap later Lawson drops back to lead the next riders around. I just practice those lines Lawson left behind for a lap and the flag waves us in.

Everyone is more excited as he gets off his bike this time. Some are getting time cards as fast as they can, others want to talk to Eddie. Most want to thank him for guiding them around, tell him how much it helped to see it done right.

As riders read out their time cards to Code, back at the registration area, it’s obvious everyone was going faster. Two riders broke the 1:50 barrier and were into the forties. Most of us were at least five seconds faster the second session than the first session, with the same progression downward in lap times. My time card for the second session started where it left off the last session and then dropped a couple of seconds for the laps where the Gang of Three chugged around the course. Then came two laps another couple of seconds faster where I’d gotten past my partners and followed Lawson. Finally there was a lap of following no one, another second faster, a low 1:50, missing the forties by not holding the throttle open another breath going into Nine. One good lap would have done it, with all the corners done right.

A video tape is brought in and a tape player hooked up. Everyone crowds around the small portable television. Watching the bikes come through Six, we all strain to look at ourselves, on a racetrack, on fast bikes, with Eddie Lawson just ahead of us. Looks of recognition appear on faces, riders smiling when they see themselves.

When the cameramen were taping us, they left the microphone on, so their comments blurt out of the television. “That guy is way close,” an anonymous voice says. “Look at this guy,” says another. The color commentary turns out to be not offcolor, not too harsh, and occasionally funny.

Lap after lap we buzz around in miniature as the sun goes down. No one looks disappointed as he slips away. The war stories are yet to begin. “Didja see me pass Eddie in nine?” Several people are asking when the next session will be held or when the Superbike school will return to Laguna Seca.

Next year Code plans to expand the school. Details are being worked out, but he wants to conduct the school in conjunction with the Superbike nationals. So far he has arrangements for the school on the days following the nationals at Daytona, Louden, Elkhart Lake, and Seattle, with a normal series of classes held at Riverside and Laguna Seca. If things go according to plan, the standard school will be held the day or two days after the big race and an advanced school with Eddie Lawson will be held the following day.

Leaving the race track that day was not like leaving the races. I didn’t have to load up a bike or figure out how I was going to fix whatever broke. Instead, the school’s mechanics were going over all the Kawasakis, checking all the things I didn’t have to.

As an introduction to racing, the school is excellent. It gives a person track time and guidance that isn’t available to the beginning roadracer any other way, and without the need for equipment like a motorcycle or leathers. It could also be a good way to discover that racetracks aren’t fun, though I’ve never met anyone who’s been on one who felt that way. As a school for street riders, Code’s class has less direct benefits. He’s not going to point out all the potential dangers of street riding and how to avoid them. Instead, riders can discover their limits safely and at moderate expense. All the safety-conscious riders I’ve heard say they “ride within their limits” would be better and safer riders, I’m convinced, if they had an opportunity such as this to find out just what those limits are. They might even be able to raise those limits, and in so doing, have more fun being better riders.

There is a cost to all this fun. This year it has been $130 for Riverside and $140 for Laguna Seca, including the bike and equipment, with extra insurance costing a few dollars more. Next year the prices might rise because of higher track costs, though Code hopes to keep the increase down to $10. Reservations are required in advance, through California Superbike School, P.O. Box 3743, Manhattan Beach, Calif. 90266. (213) 484-9323. If that sounds like an endorsement, the sound is correct.