ARIEL HT3

Neither Mud Nor Rock Nor Lack of Two-Stroke Buzz Speeds This Classic Trialer on its Appointed Loops

Henry N. Manney III

Ever heard of Sammy Miller the trials king? Then you might possibly remember that in between road racing NSUs and before Bultaco the good Sammy carved out quite a respectable reputation on an Ariel trials bike, license GOV 132. Not only did he win everything worth winning, Miller pared a 500 pushrod Single down to 245 lb. approx. So did Sammy have a lot to do with this salon bike? Not too much really but Ariel always had a lot to do with trials since they started, practically, or at least since it was twigged that Ariel wasn’t going to cut it road racing. Hence Mr. Miller’s contract with the firm.

Ariel history we aren’t going into as they follow the same pattern as all the other makes that started with bicycles back when the Brits had just quit painting themselves blue. At least the young firm had the sense to be original, building a side saddle big-wheeler, the manner of propulsion being via one left-footed crank. History draws a veil over the antics of this Monty Python conveyance as well as what the blushing young bride said to hubby when he tried to teach her how to ride it. Can you imagine? And in long skirts too. At any rate Ariels managed to continue in production while others didn’t (see Peter Hartley’s book) and eventually got quite a decent slice of the market, thanks to the efforts of Edward Turner (see Triumph) etc. and Val Page the designer ditto ditto. Their big effort, besides the celebrated Square Four that almost put the company under, was to modernize if one can use that word the line of hoary old thumpers which led, in the middle Thirties, to the stylish Red Hunter line that still looked stylish 20 years later. Turner was a genius at tarting up old models with not too much cost to the company and Page was allowed to bring them up gradually to their looks with real oil pumps, alloy heads and even (gasp, shudder) front brakes bigger than a teacup. Ariel of course was following the same path as BSA and the like with a good solid transportation machine which could be used with success in the thousands of reliability trials (see enduro) run every year. However it used to be felt that Ariels were built a little better. A works team was in existence since the ’20s and did very well in Scottish Six Days, ISDTs, Scott Trials and so forth; the only consolation to dropping these cast iron monsters in a Yorkshire bog was that everyone else’s bike was heavy too. Postwar, I think just> after Ariel sold out to BSA for inheritance tax reasons, the company went the full alloy route with its VCH Red Hunter which, along with the importation of some new blood to freshen up things, really led to the HT3, its companion HT5 and two scrambles (mx) versions of same. Having a 350 at this time, in England at any rate, didn’t necessarily mean that the buyer had less money or anything snob like that; all the cycle companies made 350s and probably sold more of them than the bigger 500s due to cheaper running costs, a slight but definite decrease in weight (for road use anyway) and more important a considerable reduction in insurance and Road Tax levies. A quid was still a quid.

Now the reader knows all about English bikes with their 145 lb. frames, “competition models” with just a welding-rod guard over the exhaust pipe, and dirty great sidecar lugs on 250s so the amazing factor in the H (Hunter) T (trials) 3 was that the frame, at any rate, was designed from a clean sheet of paper and not makedo with an old pile left over from the Kaiser War. A rather sophisticated weld-up of sheet steel formed the backbone, a twogallon alloy tank sat on top, an early version of offset handlebar clamps graced the fork crown, the massive single downtube braced the front and bigod there was even a rectangular section proper swing arm for the rear suspension. Ariels had pioneered Anstey link-type rear suspension just after the war along with their version of teles but all this was undamped; I had bought a used Square Four at Pinks of Harrow in 1948 with this setup and covered most of France with it. After the ex-WD 350 rigid Matchless which preceded it, the Ariel was heaven but of course there was too little suspension movement for sporting use. At any rate, the all alloy engine was derived from the VCH with nickel-iron liner for the cylinder while the cylinder head had the Ariel “pair of spectacles” bronze valve seats cast in. Specially prepared for low speed torque, the engine's ports were ground and polished, the flywheel assembly mounted on heavy duty rollers plus one ball bearing, the big end was looked after by a large double-row bearing plus a Norton dual plunger pump and on the 350 anyway b and s worked out at 75 x 85 mm with a 7:1 CR, no horsepower mentioned. Sparks were provided by a Lucas comp “Wader” magneto which was driven by chain in its little polished case, carburetor an Amal Monobloc 376 (1 & 1/16 in.) 1 IT although remote float models were also fitted and the separate and rather special version of the Burman GB 47 gearbox was offered with ratios of 1.57, 2.44 and 3.2 which, when paired with eight or nine different countershaft sprockets, gave a speed to suit anyone except perhaps Lake Bonneville. Along with the jaunty upswept exhaust pipe, full width front hub and Trials Universal (no prize for guessing what brand) 4.00-19 back 3.00-21 front you have a really nice trials bike. Wheelbase 53 in., handlebar width 21 in., saddle height 32 in., spring steel footpegs no less and a dry weight of 285 lb. No Bultaco but considerably less than its opposite number Matchless which scaled out around 400. By the standards of the day the HT3 was revolutionary and the Ariel comp department really took some care over it.

As you may well imagine, British-made 350 trialers do not actually abound in this country but Dr. James Forrest of Lynwood, Calif, not only has two of them but they are of consecutive numbers, RT 226 and 227. The salon bike, a 1957 model, was originally imported by Johnson Motors seems to me and then sold by Ted Evans to a desert rat who licensed it, ran in several local trials, and then added two Big Bears plus three Greenhorns to the score. In the k59 Greenhorn he finished 2nd in the 350 class, according to old magazines. The bike only survived the chopping and modifying that went on with No. 227 by falling in a water hole at a Whittier Narrows trial and sticking itself solid. New bits were bought but not installed as the then owner was in a rush so he bought a Matchless and relegated 226 to a tasteful selection of orange crates. At that there weren’t too many HT3s about as roughly 325 were made over ’56 through ’59 including a few early rigid models. Anyway, the wreckage was eventually turned over to Clyde Earl, an old bike freak at Johnson Motors, who kept it a couple of years and thence to Dr. Forrest. After a lot of moaning groaning and improvising 226 surfaced in its present original form while later acquisition 227, which appears with some regularity in vintage motorcycle trials, is naturally less cherry with the wrong tank, for instance. Both bikes are lucky not to have fins broken off, big dents in the clutch derby, nasty scrapes on the polished alloy cases etc. as one Big Bear used to be enough to junk a bike.

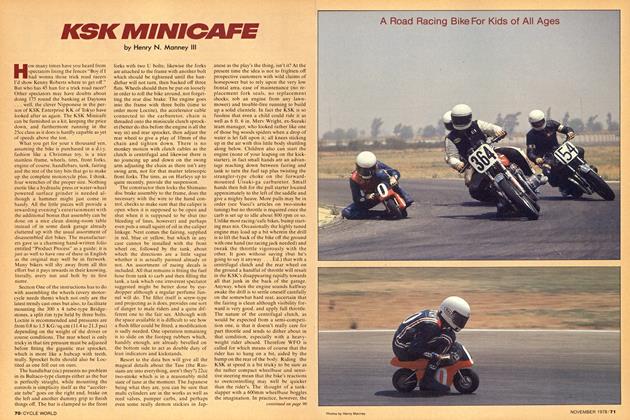

The photo day was lots of fun naturally even if we couldn’t dig up any mud ... or at least legal mud ... in the area. Our Designated Pom, Brian Slark, came along to help out and also lend his vast experience in case. Actually very little help was needed barring cold drinks (Mme. Forrest took care of that) as the Ariels with their gigantic flywheels started easily and came pot. . . pot . . . potting up the road looking like a couple of clipper ships under full sail, the alloy and chrome all a twinkle. Two-strokes may do the job better and definitely easier but the HT3s seemed to be so dignified about the task, going pot . . . pot . . . pot more or less at the same rpm wherever they went. All bikes have their Noises but these made their own symphony with fins ringing, mag chain rattling, piston slapping gently, valves clicking and as Slark said all it needed was a bit of steam to be a real James Watt-Mobile. What with the long stroke and all, there certainly seemed to be power enough to do the job, especially since Dr. Forrest could idle down to practically traction engine speed while slogging up a rock face. Altogether the Ariels gave an atmosphere of ineffable peace, contentment, and a sense of going back to the way things used to be before expensive gas, wogs with atomic bombs, and doubleknit suits. A hill full of these should be a great sight and whereas there are quite a few vintage trialers around including Matchboxes and Nortons, Dr. Forrest, (1 1612 S. Atlantic Ave., Lynwood, Calif. 90262) is looking for more company. Come join in the 19th century! Bring your flat 'at! S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

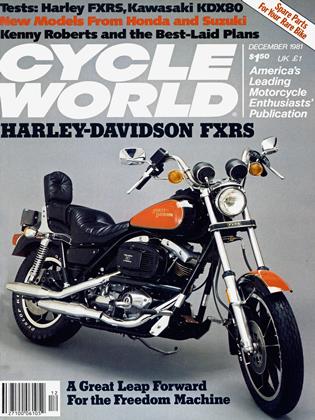

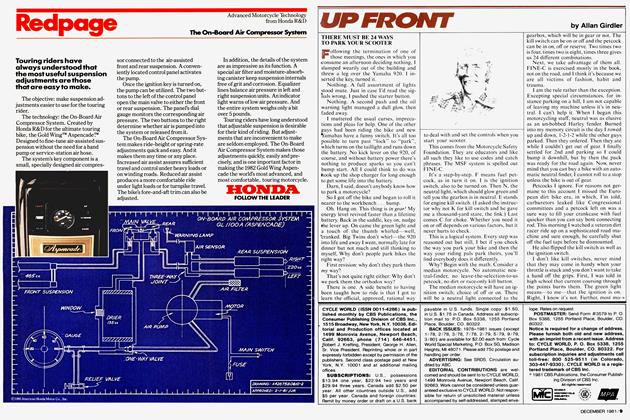

DepartmentsUp Front

December 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1981 -

Features

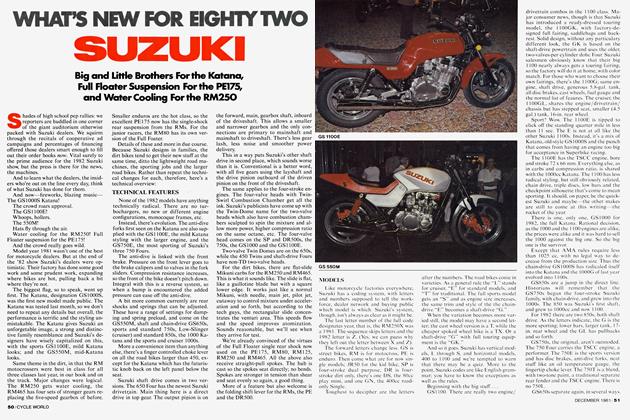

FeaturesWhat's New For Eighty Two Suzuki

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsBook Reviews

December 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Features

FeaturesA Guide To Orphan's Homes

December 1981 By Dee Winegardner