Wells Bennett

HISTORY

Fastest on a Four Border-to-Border

J.L. BEARDSLEY

IF IT had two wheels, Wells Bennett would ride it. If it had an engine, he'd travel faster, and farther, across mountains, deserts or mud, to more miles of crosscountry records than any other man since motorcycles were invented.

Born in Wichita, Kans., in 1891, Wells Bennett rode bicycles as a boy. When the first Indian motorcycles appeared around 1904, he was one of the first to own one of these light, belt-drive machines-and was the envy of every boy in town.

His boyhood chum was Ray Weishaar, later a famed Harley-Davidson race rider, who was soon mounted on an Indian, too. "We grew up on wheels," Bennett relates.

At 15, Wells Bennett was racing on local half-mile tracks by stretching his age a little. He gained familiarity with the early makes-Reading-Standard, Thor, Yale, Racycle, M & M, Merkel, Pierce and Wagner-but Indian was his first favorite.

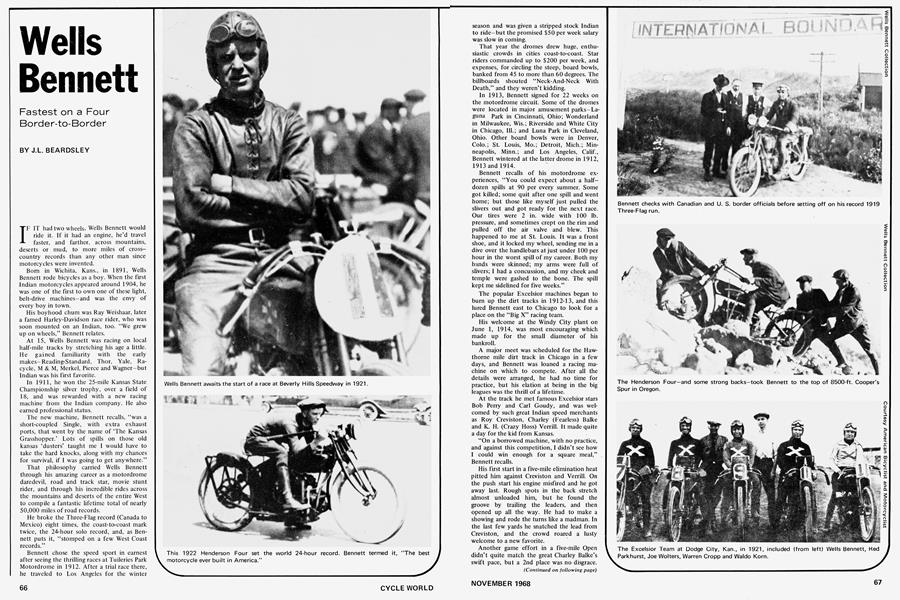

In 1911, he won the 25-mile Kansas State Championship silver trophy, over a field of 18, and was rewarded with a new racing machine from the Indian company. He also earned professional status.

The new machine, Bennett recalls, "was a short-coupled Single, with extra exhaust ports, that went by the name of 'The Kansas Grasshopper.' Lots of spills on those old kansas 'dusters' taught me I would have to take the hard knocks, along with my chances for survival, if I was going to get anywhere."

That philosophy carried Wells Bennett through his amazing career as a motordrome daredevil, road and track star, movie stunt rider, and through his incredible rides across the mountains and deserts of the entire West to compile a fantastic lifetime total of nearly 50,000 miles of road records.

He broke the Three-Flag record (Canada to Mexico) eight times, the coast-to-coast mark twice, the 24-hour solo record, and, as Bennett puts it, "stomped on a few West Coast records."

Bennett chose the speed sport in earnest after seeing the thrilling races at Tuileries Park Motordrome in 1912. After a trial race there, he traveled to Los Angeles for the winter season and was given a stripped stock Indian to ride—but the promised $50 per week salary was slow in coming.

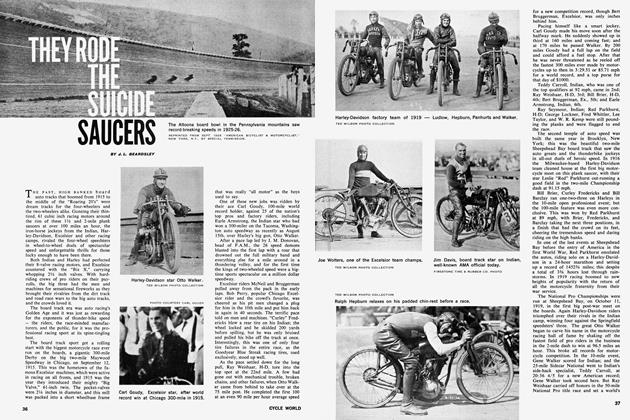

That year the dromes drew huge, enthusiastic crowds in cities coast-to-coast. Star riders commanded up to $200 per week, and expenses, for circling the steep, board bowls, banked from 45 to more than 60 degrees. The billboards shouted "Neck-And-Neck With Death," and they weren't kidding.

In 1913, Bennett signed for 22 weeks on the motordrome circuit. Some of the dromes were located in major amusement parks-Laguna Park in Cincinnati, Ohio; Wonderland in Milwaukee, Wis.; Riverside and White City in Chicago, 111.; and Luna Park in Cleveland, Ohio. Other board bowls were in Denver, Colo.; St. Louis, Mo.; Detroit, Mich.; Minneapolis, Minn.; and Los Angeles, Calif., Bennett wintered at the latter drome in 1912, 1913 and 1914.

Bennett recalls of his motordrome experiences, "You could expect about a halfdozen spills at 90 per every summer. Some got killed; some quit after one spill and went home; but those like myself just pulled the slivers out and got ready for the next race. Our tires were 2 in. wide with 100 lb. pressure, and sometimes crept on the rim and pulled off the air valve and blew. This happened to me at St. Louis. It was a front shoe, and it locked my wheel, sending me in a dive over the handlebars at just under 100 per hour in the worst spill of my career. Both my hands were skinned; my arms were full of slivers; I had a concussion, and my cheek and temple were gashed to the bone. The spill kept me sidelined for five weeks."

The popular Excelsior machines began to burn up the dirt tracks in 1912-13, and this lured Bennett east to Chicago to look for a place on the "Big X" racing team.

His welcome at the Windy City plant on June 1, 1914, was most encouraging which made up for the small diameter of his bankroll.

A major meet was scheduled for the Hawthorne mile dirt track in Chicago in a few days, and Bennett was loaned a racing machine on which to compete. After all the details were arranged, he had no time for practice, but his elation at being in the big leagues was the thrill of a lifetime.

At the track he met famous Excelsior stars Bob Perry and Carl Goudy, and was welcomed by such great Indian speed merchants as Roy Creviston, Charley (Fearless) Balke and K. H. (Crazy Hoss) Verrill. It made quite a day for the kid from Kansas.

"On a borrowed machine, with no practice, and against this competition, I didn't see how I could win enough for a square meal," Bennett recalls.

His first start in a five-mile elimination heat pitted him against Creviston and Verrill. On the push start his engine misfired and he got away last. Rough spots in the back stretch almost unloaded him, but he found the groove by trailing the leaders, and then opened up all the way. He had to make a showing and rode the turns like a madman. In the last few yards he snatched the lead from Creviston, and the crowd roared a lusty welcome to a new favorite.

Another game effort in a five-mile Open didn't quite match the great Charley Balke's swift pace, but a 2nd place was no disgrace.

Bennett had earned some cash—and a place on the Excelsior race team.

After the eastern drome season ended in October, 1914, Bennett went to Los Angeles for the winter season of dirt track racing, and was employed by local Excelsior dealers between meets.

The old Ascot Mile speedway at that time was becoming a famous racing center for both bikes and automobiles, with added thrill show specialities. One attraction was a three-cornered exhibition race between Barney Oldfield in his land-speed record car, the "Blitzen Benz"; Lincoln Beachey, America's greatest stunt flyer, in his Curtiss Pusher and Wells Bennett, representing the motorcycle speed demons.

The act opened with Beachey swooping low in front of the grandstand, using his forward landing wheel to knock down pop bottles standing on the track. Afterward, as the trio sped around the track, Beachey hovered so low he actually nudged the top of Bennett's helmet with his rubber-tired wheel.

Wells Bennett's reputation for daredeviltry soared after this stunt. Film makers soon hired him for motorcycle sequences at $30 to $45 a day, which was a good wage for those times.

The motordrome mania diminished in 1915, and Bennett finished his career there ranking 2nd in all-time points among 60 contract riders.

He was in charge of the motorcycle squadron in the film "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" in 1917, when the Hollywood Knights Of The Round Table went modern to ride steel steeds.

It didn't do Bennett's reputation any harm when he rode the full half-mile long sea wall at Los Angeles. The concrete path was only 14 in. wide with a 20-ft. drop into the Pacific. He also climbed the foot path to a U.S. Forest Service lookout in the precipitous Sierra Madre mountains, a feat called impossible on wheels until then.

In addition, Wells Bennett could ride the long trails. He won a 1000 mile endurance run through the Oregon mountains sponsored by the POR TLAND JOURNAL.

With the end of World War I, competition events again were scheduled. Bennett lost no time in going after point-to-point records in the West. On Jan. 6, 1919, he took Roy Jones as passenger in a stock Excelsior with sidecar for a 132-mile race against time from Los Angeles to San Diego, setting a new mark of 2 hr., 44 min.

Then on Jan. 19, Glen Stokes, a famous Excelsior rider, was Bennett's passenger as he scaled the hazardous Ridge Route for 125 miles, shooting the unpaved 17-mile tangle called "The Route of 1000 Curves" for another sidecar record, this time from Los Angeles to Bakersfield in 4 hr., 4 min.

On Feb. 12, he did a re-run, using a Bennett underslung torpedo sidecar, and a Series 19 stock Excelsior sealed in high gear. With Ted Thurston as passenger, Bennett battled fog, a rough mile detour, and frost in the high elevations, but slugged through for a new 3 hr., 7 min. record.

The going never was too tough for Bennett. A vivid example of his stamina came that same year, on March 26. Roy Artley, another noted distance rider, on a Henderson Four, and Bennett, on an Excelsior, started a "race" from San Diego to Phoenix, Ariz., 394 miles across the desert. Near Mountain Springs, 85 miles out, Bennett charged down a treacherous slope marked by a series of S turns, rocks and holes. He plunged into a washout, executed a complete somersault, and landed hard. One leg and shoulder were paralyzed, and Bennett was unable to crawl out from under the machine.

A following auto party eventually arrived and administered first aid. The fork had been bent and this was straightened. To everyone's amazement, Bennett insisted on mounting and riding on, though one arm was in a sling, and his shoulder pained him severely. Thirtytwo miles later, he walked into a doctor's office in El Centro, Calif., where his torn shoulder ligaments were treated.

It should be remembered that crosscountry travel back in 1919 BC (Before Concrete) held hazards unknown today.

"Prior to 1920," Wells Bennett says, "there were very few paved roads from coast to coast; and from Canada to Mexico very little was even graded. From Los Angeles to Indianapolis, a 2500 mile span, there was not one foot of concrete. Any traveler caught in a rainstorm faced a sea of mud in the prairie states. The dry powdery silt in some places was worse than sand to get through."

These were the days of corduroy roads in swampy sections of the northwest. Logs were laid across the right of way to cover the mire, and a bone-jarring ride at any speed was the result.

Yet on these rough roads, riding some of the toughest bikes ever built, Wells Bennett proved his own stamina and set records all across the Wild West. His most notable feat was setting a new Three-Flag mark in July, 1919, from the Canadian Boundary at Blaine, Wash., to Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. The distance was 1716 miles through the entire Rocky Mountain range in 53 hr., 28 min., with 2 hours of sleep. This broke the record set by the famous "Cannon Ball" Baker only two weeks earlier.

It would be easy to say that Wells Bennett closed his 1919 road triumphs with a solo San Francisco to Los Angeles record, but a close look shows just how tough a ride this was.

On Dec. 11, he roared out of the Golden Gate city on his trusty Excelsior, southward over roads that grew rougher as he neared the mountains. He then traversed the twisting curves of Niles Canyon, then sped into Pleasanton where his machine was refueled.

Outside the city of Madera, his engine suddenly "went on one," but an obliging Harley-Davidson dealer supplied him with a replacement for a broken tappet-adjusting screw; 20 min. was lost in repair.

Pounding south toward Fresno to make up time, a slow tank leak began to drip liquid dynamite on Bennett's hot engine.

Five minutes had been made up as he neared MacFarland, but a long freight train crossing wiped this out. Grimly he raced toward Bakersfield, passed a passenger train as if it were stationary, and made the 109.5 miles in 3 min. under 2 hr.-a truly outstanding mark for those days and road conditions.

He was again 10 min. ahead of the record. After a sandwich for him and fuel for his motorcycle, a tornado of dust trailed him across the desert as he bumped his way into the Tejon range.

Crossing the summit on the newly-paved tortuous 29-mile Ridge Route, he used his brake heavily on the descent. On a sharp, twisting curve, his braking effect disappeared entirely, when a rod pulled loose from the clevis. Calling on all his rough mountain riding skill, Bennett was able to take one sharp bend in stride, but there were two more. He barely missed a 100-ft. drop as he slid through the second. His speed mounted constantly. Before hitting the next turn, he was forced to throw his bike head-on against the six-foot bank on the inside, but his momentum carried him over the top, and he plunged to the pavement which angled sharply back where he was thrown 25 ft. from his machine. Luckily, he received no broken bones, but the bike had suffered a broken fork arm on one side.

Bennett re-connected the brake rod, and with a wobbling front wheel, he limped across the Broadway Bridge in Los Angeles with a new inter-city record of 9 hr., 9 min. for the 461 rugged miles from San Francisco.

On his battered Model 19 Excelsior, with sidecar and passenger, Bennett executed an encore on this March 4, 1920, spanning the distance by a slightly shorter route for a record of 11 hr., 11 min., after a battle with fog, numbing cold, and sleet in the mountains.

Then there were other tough struggles with primitive roads, Los Angeles to Needles, Chico to Sacramento, 100 miles in 100 minutes, and San Diego to Phoenix. These were epics of endurance by man and machine.

On Aug. 26, 1920, Bennett lowered the Three-Flag record to 51 hr., 4 min., for the fourth of his eight victories on this famous run.

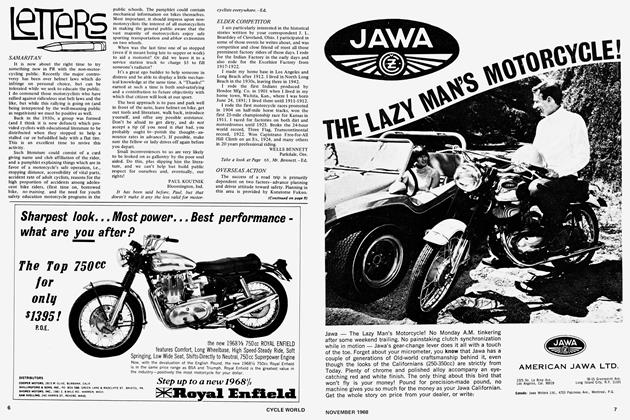

In the last of the Dodge City 300-mile Nationals on July 4, 1921, Bennett rode a fast pocket-valve Excelsior, with members of the X team Joe Wolters, Warren Cropp, and Waldo Korn, augmented by the former Harley-Davidson ace, Leslie (Red) Parkhurst.

Only Ralph Hepburn, on an eight-valve Harley-Davidson, was ahead of Bennett at 135 miles, and one reporter wrote of Bennett's bid, "Things looked hopeful until the jinx caught up with him." Three pit stops later, a cam pawl roller broke and went through the timing gear. A good ride went for nothing.

In 1921, the M&ATA banned any additional sanctions for cross-country speed runs for reasons of increased traffic hazards; but Bennett was retained by the Excelsior Company at $150 a month, plus all expenses and purses, to compete anywhere in the United States. Starting with hillclimbs, he won at Sacramento, and then scored a smashing victory over Dud Perkins, H-D's great hill champ, at the Capistrano Nationals in the 80-cu. in. Open Class, on April 9, 1922. This was rated the West's toughest hill.

(Continued on page 103)

Continued from page 69

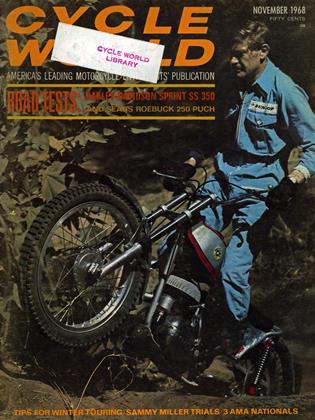

In the Henderson Four, the Excelsior company had a fine new motorcycle, and publicizing this became Bennett's next task.

On the Henderson De Luxe Four, which he calls, "The best motorcycle ever built in America," Bennett went after the world

24-hour solo record on the 2-mile Tacoma, Wash., speedway, and on May 30 and 31, 1922, racked up a whopping total of 1562-54 miles to break a mark that had held for years. Only one set of specially-built Firestone tires was used.

Next followed two transcontinental runs. On the second, Bennett broke Cannon Ball Baker's Los Angeles-New York time on Oct.

25-31, 1922, lowering it to 6 days, 15 hrs., and 13 min. on the fast Henderson Four.

He rolled out the 80-cu. in., 40-bhp Excelsior that carried him to victory at Capistrano, and assaulted the Mt. David 900-ft. slope near Cottage Grove, Ore., in May, 1923, and was the only rider to top the hill, scaling the 75 percent grade in 13 sec.

Later that year, Bennett dodged police for another Three-Flag record of 39 hrs., solo, and returned in a sidecar for a three-wheel mark of 54 hr., 42 min. for his eighth Canada-to-Mexico sprint.

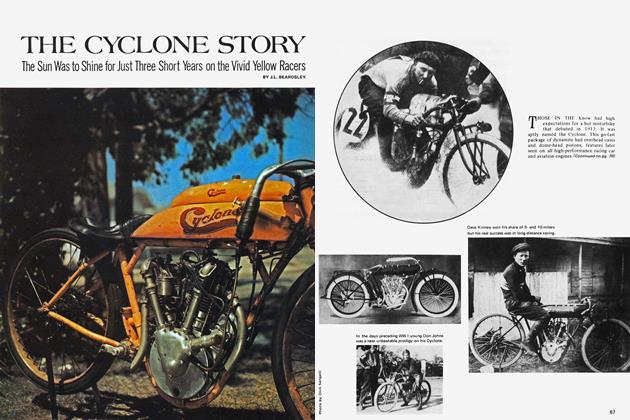

Bennett invested his rewards from feats on road and track in an Excelsior-Henderson Sales Agency, in Portland, Ore., after retirement, but all of his two-wheeled adventures came to a sensational climax in July 1924.

MOTORCYCLIST & BICYCLIST ILLUSTRATED, hailed it this way: "Riding again in the limelight, for a few brief, dazzling hours, Wells Bennett and his Henderson have made a new and totally different record."

At the Hood River, Ore., American Legion Hillclimb, his attempt to scale the side of towering Mt. Hood won wide interest—including that of newsreel cameramen.

Fox-Movietone News cameras filmed him as he churned across two glaciers on the north slope and battled the boulder-strewn east side above timberline to Cooper's Spur to reach a fantastic 8500-ft. elevation, using only engine power of the Henderson's four cylinders. Here a 600-ft. rope was to be anchored to wind on a rear wheel pulley for the near-vertical ascent to the summit. A sudden gale and snow storm drove the pack horses off the trail and this had to be abandoned, but Bennett had climbed higher than any other motorcyclist ever has—to this day!

After selling his motorcycle business in 1930, Wells Bennett became a service representative for Ford Motor Co. for 14 years, then retired to a ranch at the foot of Mt. Hood. Today at age 76, Bennett still lives in the scenic Cascade Mountain country where he likes to recall his exciting years of risking his life on the dirt, the dromes, and the wild mountain trails. He was one of those hardy test pilots who developed a new sport and a new industry; who brought thrills to thousands; and who rates as the greatest cross-country rider of all time.