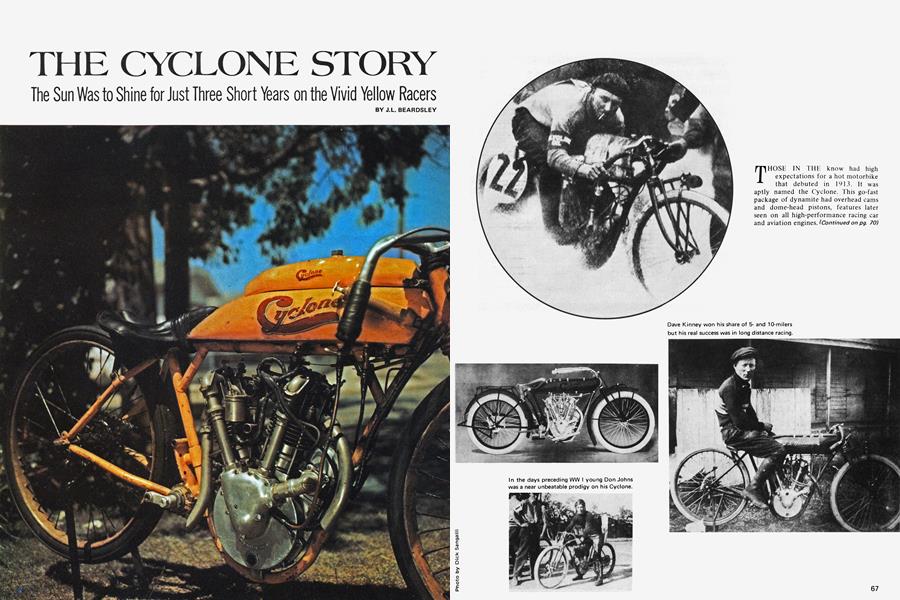

THE CYCLONE STORY

The Sun Was to Shine for Just Three Short Years on the Vivid Yellow Racers

J.L. BEARDSLEY

THOSE IN THE know had high expectations for a hot motorbike that debuted in 1913. It was aptly named the Cyclone. This go-fast package of dynamite had overhead cams and dome-head pistons, features later seen on all high-performance racing car and aviation engines.

(Continued on pg. 70)

Continued from page 67

Designed by Andrew Strand and built by the well-known Joerns Motor Manufacturing Company in St. Paul, Minnesota, it was not only the most advanced Twin of its day, but one with a great potential for future development.

Those that first found their way onto the race tracks were yellow rockets that brought lusty cheers from spectators, and worried looks from competitors.

Early-day ’drome star J.A. McNeil is credited with having a hand in the Cyclone production, and rode one blazing mile on the Omaha, Nebraska, track in 32.4 sec. or over 1 1 1 mph!

This was so unbelievable in 1914 that the Federation of American Motorcyclists contest board refused it a rating as an official world record. But the board should have been alerted, for since 1913 reports had been coming from Minneapolis that J.A. McNeil and another board track burner, Larry “Cave Man” Fleckenstein, were winding up their Cyclones on the local ’drome at speeds up to 108 mph.

What made them go? The Strand V-Twin displaced just under 61 cu. in., but a small high-compression combustion chamber, plus positive valve action, developed high engine speed. According to their catalog this was the “secret” of their higher power and performance. The wide-flanged, gray iron cylinders were precision ground and polished inside and outside, and mounted at a 42-degree angle. The removable heads carried two large valves with a cast-iron face on a nickel-steel stem. Pistons were lightweight gray iron, lapped to a perfect fit, and carried two wide rings with large oiling surfaces.

Their unique overhead vanadium steel camshafts were driven by bevel gears. The rocker arms had tempered and ground rollers working directly on the cams. The valves were opened by a hinged yoke that eliminated all side thrust on the stems and the valve system was sheltered in a dirt-free housing.

Con rods were “I” beam steel and extra long to control side thrust; the flywheel was balanced; and the crankshaft had four-row roller bearings on the drive side and double-row, self-aligning ball bearings on the other end. The crankpin had a three-row roller bearing, while all cam and magneto drive parts ran on double-row self-aligning ball bearings.

Two oil windows showing oil level and pump flow were mounted in the polished aluminum crankcase.

On the theory that only reliable lubrication could guarantee perfect performance, the Cyclone oiling system was designed for high efficiency in a motor developing more revs than any other in production.

The Cyclone was lubricated by a combination of the splash and vacuum systems. The crankcase oil was supplied by a simple rotating cylinder pump with only two moving parts. It used a sleeve rotated by a worm gear on the camdrive shaft, admitting oil from a supply line and expelling it under pressure by a plunger through a passage in the crankcase. This was claimed to be both practical and economical in operation.

A Bosch magneto and Schebler carburetor were standard equipment on most Cyclones. And like most of the better bikes of that day, an Eclipse clutch was used.

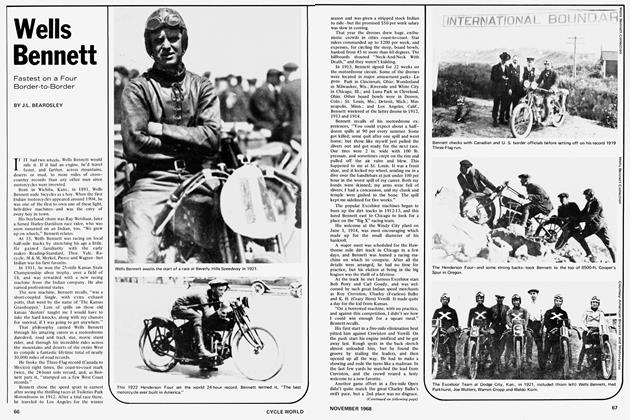

Cyclone’s bid for public acceptance was keyed to competition in a big way, and they produced both ohc and ohv racing models in 1914. The ohv was called the R-15. It has drop handlebars and 2.5-28 tires, to attract the boys with a high-voltage yen for speed. This 61-in. job was ready to roll on any track—and how they rolled!

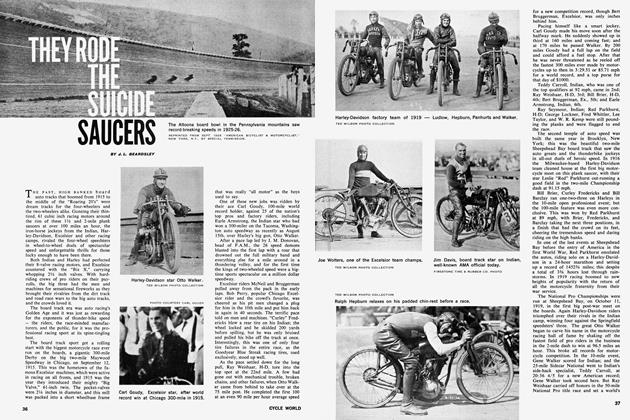

Neither of the original Cyclone team riders, J.A. McNeil or Larry Fleckenstein, were experienced on dirt tracks. But they were lucky to get a sensational Los Angeles youngster named Don Johns in their camp. Johns had won the 2-mile amateur championship in 1912 when he was only 16 years old.

(Continued on page 72)

Continued from page 70

A race meet was schèduled to entertain guests at the F AM National Convention, in St. Louis in 1914, on the very fast Maxwelton 1-mile dirt track. Under McNeil’s and Fleckenstein’s watchful eyes, young Johns climbed on a Cyclone and went into orbit.

Wells Bennett, another great speed merchant, witnessed Johns’ demonstration before the convention crowd and recalled it as some of the most sensational track riding he ever saw. With a funnel cloud of dirt trailing the flying machine, Johns was going wide open all the way; then the terrific vibration snapped one handlebar off. He wasn’t killed and it truly was a miracle.

The Cyclone speed department had seen enough to give Johns another chance at a meet on the Bakersfield mile, and here the young speed demon got the scene in focus. On September 28, 1914, Johns sliced a full 6 seconds from the fastest time of the day by Earl Roylance (H-D) and set a new track mark of 43.8 sec.

The great Harley ace, Otto Walker, was the star by winning three events; but he didn’t take the one Don Johns entered-the Cyclone prodigy trimmed Walker in a 5-mile race in 3 min., 47 sec.

The 1915 season was a banner one for Cyclone jockeys. It started on January 31, when Johns rocketed around the Ascot mile in Los Angeles for a world 10-mile flat track record of 8 min., 14 sec. He set a lap record of 49 sec., and led the 100-mile feature event to the halfway point, when carburetor failure put him out.

After this, the yellow Cyclone’s prestige soared in motor-minded Los Angeles, and when C.L. Smith, a wellknown dealer, opened his new Cyclone agency on Main Street, the enthusiastic crowd overflowed the building. When machines were displayed outside, the crowds stopped traffic on the street.

George Ashley, prominent in the New York City motorcycle trade, found a similar response when he opened his Cyclone dealership at 1213 Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn, that year.

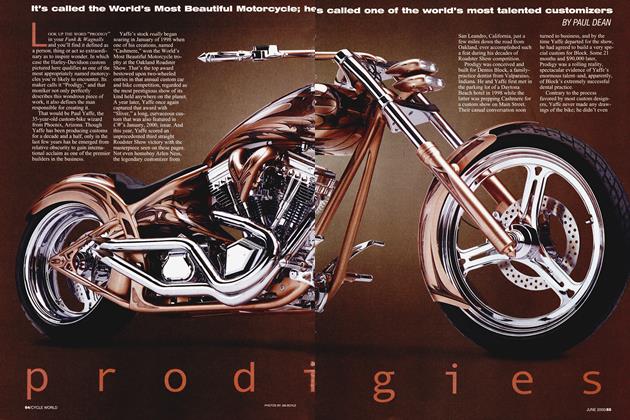

Things looked bright for the new machine. And in a day when the race track was the showroom and proving ground, the Cyclone people added two more hot track performers: Bill Goudy, brother of the famous Carl, and Dave Kinney-both gents were very hard to stay ahead of.

(Continued on page 74)

Continued from page 72

The new race team aimed for the big time. This was a particularly long shot in the 1915 300-mile Motorcycle Grand Prix at Venice, California. They made a good try, but both were eliminated by mechanical difficulties. Otto Walker went on to win the big derby on a Harley-Davidson.

But on the midwest circuit it was a different story. At the Peoria dirt oval, Johns ran away with four out of seven races on May 31, 1915.

Two weeks later, at Detroit’s championship meet on the 1-mile track, Johns won a 5-mile elimination heat and the 10-mile Pro event. And K.H. “Krazy Hoss” Verrill took a Cyclone home 1st in another 5-miler in 4 min., 24 sec. Kinney took 2nd in one 5-mile heat.

Johns started the 100-mile National at a terrific pace, but then needed oil and could not catch the winner, Jim Davis, who was setting a world record on his Indian.

Bill Goudy, Kinney, and Johns carried the hopes of the Cyclone camp in the great 300-mile International Championship on July 4, 1915, on the 2-mile Dodge City track. Thousands of fans from hundreds of miles around got their moneys’ worth in thrills.

Inez Patterson covered this “Coyote Classic” for west coast papers. She wrote that as she stood in the pit area, a “yellow blur roared past” and at her question of “Who?” a pit man answered, “That was Don Johns on a Cyclone. He’s hitting 92 miles an hour.”

Johns kept it up for 32 miles, then pitted briefly. He tore out after the new leader, Carl Goudy on an Excelsior, and caught him at the 48-mile point. But the Excelsior star wore down the low-flying Cyclone pilot and passed him at 80 miles. It was 10 miles later that Johns retired with a damaged gasoline tank. Dave Kinney was forced out with a cracked frame, but the Dodge City fans had seen a sensational show—or was it a glimpse of tomorrow?

And the smaller tracks were seeing the new speedsters, too, as at Marysville, Kansas, two weeks later on July 18, 1915. Motorcycle Illustrated reported: “The Cyclone made its initial debut on the local track. It was a good showing.”

This meet saw the 2-mile Amateur State Championship won by Winkley on a Cyclone with a good ride that pleased the crowd. Then a couple of pros: Ray Creviston (Indian) and John Gibson (Cyclone) tangled in a hot 5-mile duel with the Indian star nosing out his rival.

In August of that year, Johns had joined the Indian race team and showed up at San Jose, California, riding the Springfield bike, but Dave Kinney remained a Cyclone jockey. Kinney was 3rd in a hectic 100-mile National at Detroit on September 19, as Morty Graves set a world record of 84 min., 41.4 sec. to beat out Creviston by one yard. Both rode Indians.

Larry Fleckenstein remained loyal to Cyclone and trounced both these Indian aces plus his old partner, J.A. McNeil, now on an Excelsior, at the St. Joseph, Missouri, half-mile oval the following October. He scored five wins in five starts over this stiff competition.

The best distance rider Cyclone had was the durable Dave Kinney. He gave Excelsior star Bob Perry such a chase in the 100-miler at Phoenix that Perry was forced to a world record to beat him. This wild speedfest saw Don Johns take a big spill, and Ray Creviston’s motor burst into flame. These old-time speed demons never spared the horses trying to get there first.

Though there was a 1916 model Cyclone announced, trouble lay ahead. A notice appeared in Motorcycle Illustrated of January 10, 1916, calling a meeting of creditors of the Joerns Motor Manufacturing Company, to be held in the offices of Referee Gideon S. Ives. Bankruptcy action was in progress.

Kinney continued to ride his Cyclone on the west coast for some six months before he saw the handwriting on the wall. He won a 10-mile event at Stockton over a good field, for his last ride. It was then announced he had joined the Indian team.

For Indian, he won the 5and 10mile world flat track records before the summer was over, and many other fine performances were added before he enlisted in the armed services at the outbreak of World War I. After the war he became a field representative for Goodyear motorcycle tires.

In race meets after the war there were a few Cyclones, ridden by enthusiasts who had learned to like the swift, yellow rockets. But no more loyal or dedicated Cyclone rider existed than former Marine Sergeant Parker Abbott. He cut down a Twin into a single-cylinder race job that competed the halfmilers in Colorado and nearby states with much success until 1921.

But the sun had long since set on this worthy design. Cyclones might have revolutionized the industry had they broken sales records as fast and as often as they had race records.

In 1919, the Excelsior company tried to revive the ohc engine. Former Cyclone riding star and mechanic J.A. McNeil had a prominent role, along with their star rider-engineer, Bob Perry.

Three machines were built, but the project ended in disaster when Bob Perry met death while testing one at Ascot Speedway. The word was out that the ohc was too fast for any flat track, or a jinx engine-or both.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1970 -

Features

FeaturesNight Rider

February 1970 By Stuart Munro -

Features

FeaturesHow To Teach Your Girl To Ride

February 1970 By David C. Hon -

Special Color Feature

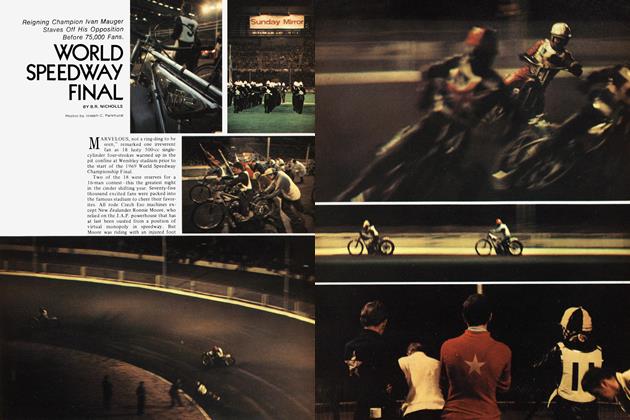

Special Color FeatureWorld Speedway Final

February 1970 By B.R. Nicholls