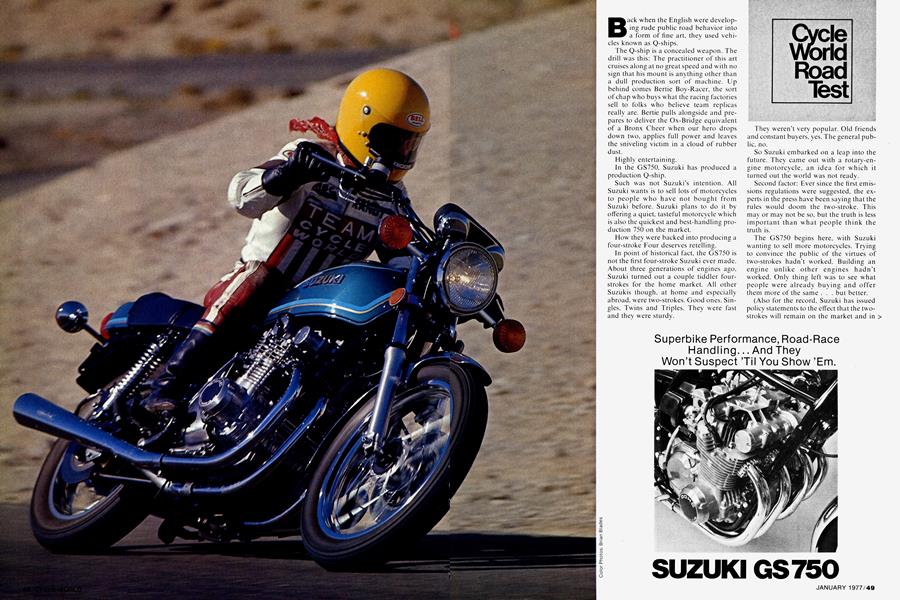

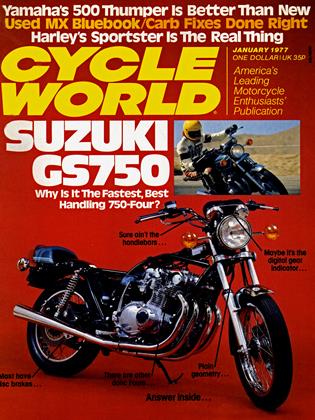

SUZUKI GS750

Cycle World Road Test

Superbike Performance, Road-Race Handling. ..And They Won't Suspect `Til You Show `Em.

Back when the English were developing rude public road behavior into a form of fine art. they used vehicles known as Q-ships. The Q-ship is a concealed weapon. The drill was this: The practitioner of this art cruises along at no great speed and with no sign that his mount is anything other than a dull production sort of machine. Up behind comes Bertie Boy-Racer, the sort of chap who buys what the racing factories sell to folks who believe team replicas really are. Bertie pulls alongside and prepares to deliver the Ox-Bridge equivalent of a Bronx Cheer when our hero drops down two, applies full power and leaves the sniveling victim in a cloud of rubber dust.

Highly entertaining.

In the GS750, Suzuki has produced a production Q-ship.

Such was not Suzuki’s intention. All Suzuki wants is to sell lots of motorcycles to people who have not bought from Suzuki before. Suzuki plans to do it by offering a quiet, tasteful motorcycle which is also the quickest and best-handling production 750 on the market.

How they were backed into producing a four-stroke Four deserves retelling.

In point of historical fact, the GS750 is not the first four-stroke Suzuki ever made. About three generations of engines ago, Suzuki turned out a couple tiddler fourstrokes for the home market. All other Suzukis though, at home and especially abroad, were two-strokes. Good ones. Singles. Twins and Triples. They were fast and they were sturdy.

They weren’t very popular. Old friends and constant buyers, yes. The general public, no.

So Suzuki embarked on a leap into the future. They came out with a rotary-engine motorcycle, an idea for which it turned out the world was not ready.

Second factor: Ever since the first emissions regulations were suggested, the experts in the press have been saying that the rules would doom the two-stroke. This may or may not be so. but the truth is less important than what people think the truth is.

The GS750 begins here, with Suzuki wanting to sell more motorcycles. Trying to convince the public of the virtues of two-strokes hadn’t worked. Building an engine unlike other engines hadn’t worked. Only thing left was to see what people were already buying and offer them more of the same . . . but better.

(Also for the record, Suzuki has issued policy statements to the effect that the twostrokes will remain on the market and in > will be met. far as can be predicted. There are even claims that two-strokes suffer less from emissions controls than four-strokes do.)

The GS750 begins with the engine and yes. the Suzuki inline Four with double overhead camshafts looks mighty like the Kawasaki engine of the same type and configuration. The GS has a wide bore for its displacement and consequently a short stroke, the classic way to achieve an engine willing to rev high and live long. The wide bore also allows room for large valves, that is, more power at high rpm. The exhaust valves are coated with Stellite, so they will last at high rpm despite not having leaded fuel for lubrication.

Most of the internals are state-of-theart; three-ring pistons, cast iron liners, roller crank, gear primary drive between cylinders 3 and 4.

Two exceptional items. First, valve clearance is adjusted by juggling little discs, supplied in increments of 0.005", and without having to first remove the camshafts. Suzuki has designed a clever tool, with which you depress the cam followers so the discs can be traded about.

The other item is a timing chain which doesn’t need to be adjusted. The patented self-adjuster measures play. When the chain stretches or expands with heat, a spring-loaded plunger with sort of a rächet arrangement moves against the chain and takes up the slack.

Carburetors are standard 26mm Mikunis and the exhaust system is four-intotwo, no attempt at tuning. Compression ratio is 8.7; 1. the better to use no-lead fuel.

All this sounds mild, and it is . . . to a point. What with flocks of 750 Fours, Triples and Twins for sale now and in the recent past, Suzuki needed to do something to be sure the public would think of the new bike as more than just another new bike.

The tuning in this case is mostly camshaft and valve timing designed to produce a lot of power. It’s also a twostage type of power, with calm willingness from idle to 6000 rpm and All Hell Breaking Loose from 6 thou to the redline at 9000.

The GS750 chassis’ chief distinguishing feature is its 59" wheelbase; long for the engine displacement and the bike’s weight and the conventional way to insure stability in a straight line. The frame has nothing unusual in its specifications or dimensions.

Suspension tuning, though, shows a lot of careful thought. Initial damping at forks > and rear shocks is quite light. Even with average fork seal drag, small bumps and hops are absorbed softly: the rider can look down and watch the ripples disappearing into the forks while not being able to feel them. Rebound is average. In theory the GS750 could pump itself down onto the stops. In real life, it doesn’t happen. Spring rates at both ends work out nearly perfectly, for a good ride and excellent handling, as will be detailed presently.

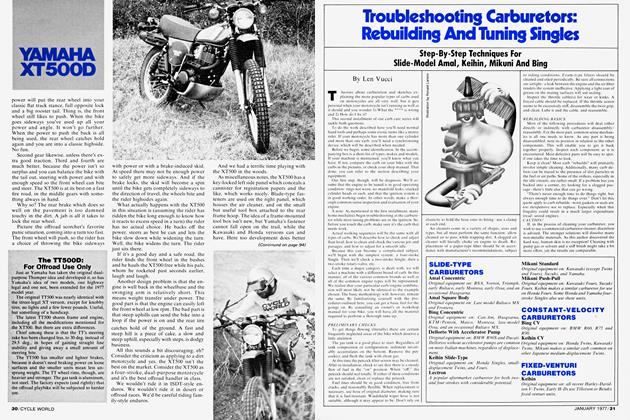

FRONT FORKS

Description: Kayaba fork, HD 315 oil Fork travel, in.: 6.0 Engagement, in.: 4.1 Spring rate, lb./in.: 32/58 pro gressive Compression damping force, lb.: 5 Rebound damping force, lb.: 11 Static seal friction, lb.: 15 Remarks: Suzuki has radically changed the suspension on their road machines this year and for the first time, they have come up with units that offer a soft ride. The major change is a reduction in compression damping which allows the front suspension to react to small bumps on surface streets and/or concrete seams on freeways. Like the compres sion damping, the progressive spring is perfect for normal riding. If there is a flaw, its rebound damping. At 11 lb. it is too light for the spring and allows the wheel to return too quickly if potholes are encountered. This will not be an important consideration, however, un less the streets in your area are un usually rough. Static seal friction is a little high. Perhaps next year Suzuki will go to a Yamaha style teflon coated seal which would make the ride as plush as current design allows.

REAR SHOCKS

Description: Rear shock, air! oil mix, non-rebuildable Shock travel, in.: 3.4 Wheel travel, in.: 4.0 Spring rate, lbjin.: 108 Compression damping force, lb.: 6 Rebound damping force, Ib: 130 Remarks: Like the forks, GS Suzuki shocks have very light compression damping. Again, the reason is to provide a soft ride under normal condi tions. The spring rate is well suited to a 150 to 185 lb. rider unless the machine is equipped with a lot of touring equip ment, If that is the case, a stiffer spring is in order. Rebound damping is ideal for the standard spring. We suggest no modifications unless you plan on going production racing. Tests performed at Number One Products

How Suzuki did it for the GS750 is the same way they did it for the PE250. They sent experienced riders into U.S. riding conditions, they asked for complete reports and they followed the advice they asked for. How simple it is once explained and when do you reckon the other makers will figure it out?

There are trends in motorcycles just as there are trends in everything. In this case, a completely modern road bike must have cast wheels, collector exhausts, double front disc brakes and one disc in back, and some sort of semi-streamlined rear bodywork.

Against fashion, we have cost. The factories decide which hot items the public wants and is willing to pay for.

The Suzuki GS750 gets disc brakes, one per wheel, collector exhausts and a slick integrated rear fender. As extra little touches, the GS has instrument lighting in fed, the better to not dazzle the eyes, and the instrument panel has a digital gear position indicator. Oh, drive is via chain and a five-speed transmission.

At the outset, the initial impression, the GS750 is either an attractive motorcycle or a short-stroke Kawasaki Z l, depending on the viewer's bias.

The initial impression is a disguise.

Perhaps the reader is aware of a tiny storm raging in the motorcycle advertising world at present, the one in which one outfit says its new model outperforms the others in class.

Rather than get involved with that, we will make only claims we can document.

Our test Suzuki GS750 did the standing quarter mile in 12.83 sec.

The GS750 is far and away quicker than any current 750 we’ve tested. The GS750 is the second-quickest 750 in our experience, the quicker having been the early Kawasaki Triple, now of fond memory. We can’t say about the few exotic 750s we haven’t tried.

We can say the GS750 is quicker than the other 750s we’ve tested and quicker than a heap of machines packing 850cc and up.

There are in fairness two penalties for this turn of speed, both involving Suzuki’s use of tuning for the top of the rev range.

One will be noticed only at the drag strip: The GS750 is devilish hard to get off the line properly. That 12.83 time required many practice runs. If the clutch is dropped at less than 7000 rpm, the engine bogs. If the clutch is dropped at 7500 or more, the rear tire goes up in smoke. Either way, the rider is lucky to break 13 sec.

The good times come by juggling clutch and throttle, keeping the engine on the pipes while feeding the tire only as much power as it will hold. Thing is. this technique is hard on the clutch and the production unit in the GS750 will not live for more than a day under this treatment.

That’s a worry only in sactioned competition. In daily use, Suzuki’s two-stage engine tuning provides the feeling of 500cc below 6 thou in exchange for the urge of lOOOcc above 6 thou.

The GS750 is geared for easy touring; normal open road cruising means running at 3800-4000 rpm. for the best possible fuel economy, smoothness, lack of vibration, etc.

There is not much surplus power on tap at cruising speed. Open the throttles at 4000 rpm in top and one can feel the bike begin to gain speed, but at no terrifying rate. A Kawasaki KZ1000 or Zl, A BMW 750 or larger, perhaps all those 750s which will lose to the GS in formal competition, all will walk away from the GS in a top gear roll-on match.

More pertinent to daily riding is that passing other vehicles is best done with a downshift, maybe two, before swinging into the other lane. When an engine is designed to produce maximum power at high rpm, the power has to come from somewhere. In this case it comes from the mid range.

This isn't to say the power at any speed is less than adequate. Solo or two up. thé GS750 w ill easily climb any normal hill at any legal speed, in top gear with no noticeable effort. Relativity or no. a 750 is a big engine.

So all right, the GS750 goes like a streak in a straight line. What about handling?

The GS750 is even better at going well than at going fast.

What it is, is good engineering. As mentioned, the GS750 has conventional suspension and frame design. No tricks, no dazzling foo-bar components. The geometry and settings and such are all within normal parameters. Nothing in the line of rider comfort or convenience has been sacrificed for road-racing style. All these years the idea has been that to go round corners well one had to ride a machine that leaked, shook and got the rider in the small of the back.

Wrong. The Suzuki GS750 is the best handling big production bike on the road.

Learning this took some doing. At the press introduction, two staffers rode pilot bikes across three states and noted that at no time did they have less than complete control and confidence while riding as fast on w inding roads as common sense allows. No twitch. no hop. no wiggle. No front wheel wash-out, or rear wheel skid. Best of all. no dreaded high-speed w'obble.

Back in home territory and more of the same. Flat roads or curves, the GS simply (Continued on page 80) stuck to the pavement and went where aimed.

SUZUKI GS 750

Continued from page 53

To test a road bike, one must push it to its limits and the GS was so good we couldn’t find the limits, not unless we wished to do some really dumb stuff on the public highway, which we didn’t.

Instead we took the GS to a road racing circuit and spent the day By God using all the suspension compliance, steering lock, lean angle and brakes and power.

Yes, the GS does have limits. At this track the tricky part comes as you crest a hill and sweep through a downhill right, letting the bike drift to the outside, then slash across the track and haul from full right lean to full left lean while braking hard for a dip across the ripples where the cars literally rip up the asphalt.

During this sequence, which happens quicker than it can be told, the front could be felt to twitch as the chassis worked the tires—Bridgestone Super Speeds, good road tires—to their limit. At no time was there loss of control.

Nor was there loss of confidence. A good sports motorcycle is one which will do more than a sporting rider will ask. When the rider sets the pace and the line, riding is sport. When the rider has to worry about what the bike will do, he isn’t riding. He’s worrying. That’s not what we buy motorcycles for.

The GS750’s brakes are at a par with the engine and chassis. Dual front discs are nice to have but not really required. The GS brakes stopped the bike in normal distances for its weight, with no loss of control or of efficiency. The leverage of the levers is nicely tuned to the effort required and are equal to each other, that is, a firm hand and foot combine for short stops.

Having declared the GS750 to be a wonder on the road, we turn to operation . . . and fudge in two places.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 80

The first fudge involves an impression. The GS750 is a long motorcycle with a long and narrow fuel tank, putting the rider rather far back from the steering head. Bridging this gap. so to speak, are handlebars that put the grips at right angles to each other. 45 deg. off the bike's center line.

Where offroad bars or road-racing bars are horizontal, and a sailboat's tiller is vertical, the GS bars fall in the middle. Where the usual control system is to pull one side and push the other, the GS steers by swinging these wheelbarrow bars to and fro in unison.

Now. This is not in itself bad. The wrist angle seems tine, as does width and height. Actual operation is no problem. The odd part is that if one looks at the bars, they look odd and the more one looks, the more odd the bars appear. Just thought we'd mention it.

The other fudge is the seat. On that introductory ride, each of the six bikes was a pilot model and each had a slightly different padding. One of our chaps liked his very much, the other liked his not at all and until the factory reps explained that the press was supposed to rate the various paddings, each thought the other was wrong.

Anyway, when the test bike arrived it had been fitted with the actual production seat padding.

Neither of the test guys liked it. Nor did the other staff riders. Too hard. we agreed.

However, the seat padding as produced is the seat padding tested and approved by a consumer group, as it were. Thus, the seat we don't happen to like is a seat others do like. Take that for what it’s worth.

No other complaints. The nice little storage bin in the rear body panel comes in handy, passengers said the pegs and seat were fine by them, the turn signal monitor lights can be seen it' you forget to cancel the signal, the exhaust noise is a pleasant (Continued on page 95) Continued from page 82 thrumm on cruise, a mild rap at full power and barely there at all in traffic. The clutch is progressive, the gearshift positive and perhaps with shorter throws than most Japanese motorcycles have. Lacking scientific devices, we can’t say that the red instrument lights are better than green or blue or white; at least they don't do any harm. If the digital gear position monitor is something we could live without, well, gotta have a gimmick somewhere or the sales manager will think the engineers don’t care.

The punchlines: Couple years back the motorcycle makers came out with Superbikes. screaming peaks of power stuffed into flexible flyer frames. Various regulatory groups and social pressures tamed these projectiles. It became the fashion to moan about the disappearance of real performance.

Horsefeathers. The Suzuki GS750 has a great engine and a chassis to match. It’ll

outrun damn near anything, it will pass even a gas station or two and all the while it’s so smooth and quiet and mild-mannered that nobody will suspect.

Until you drop down two and roll it on.

Dead? Hell, the Superbike is better than ever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

January 1977 -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1977 By Merlin Kastlei -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

January 1977 -

Technical

TechnicalTroubleshooting Carburetors: Rebuilding And Tuning Singles

January 1977 By Len Vucci -

Features

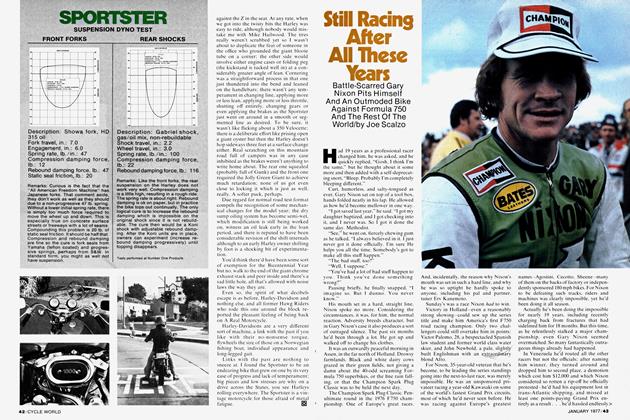

FeaturesStill Racing After All These Years

January 1977 By Joe Scalzo -

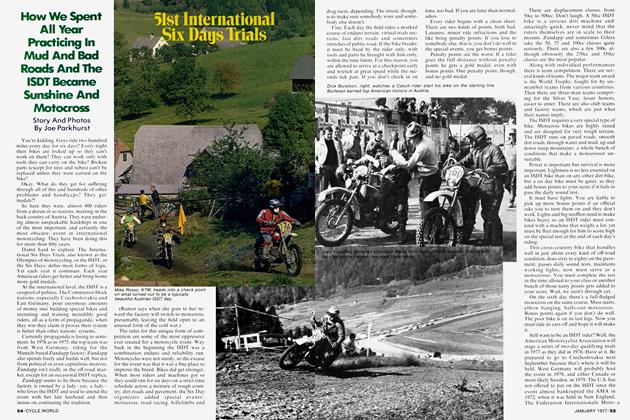

Competition

Competition51st International Six Days Trials

January 1977 By Joe Parkhurst