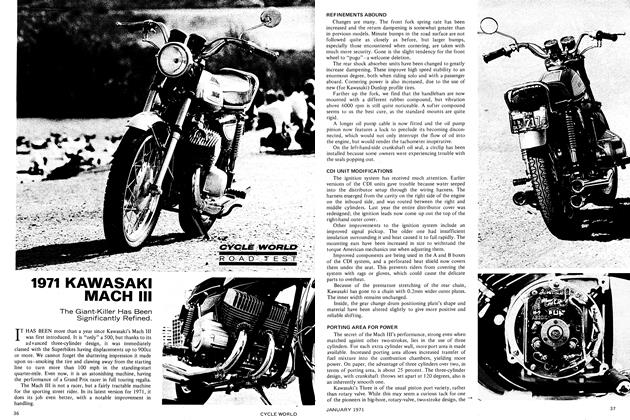

KAWASAKI 175-F1TR

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

WORLD'S FASTEST TRAIL BIKE.

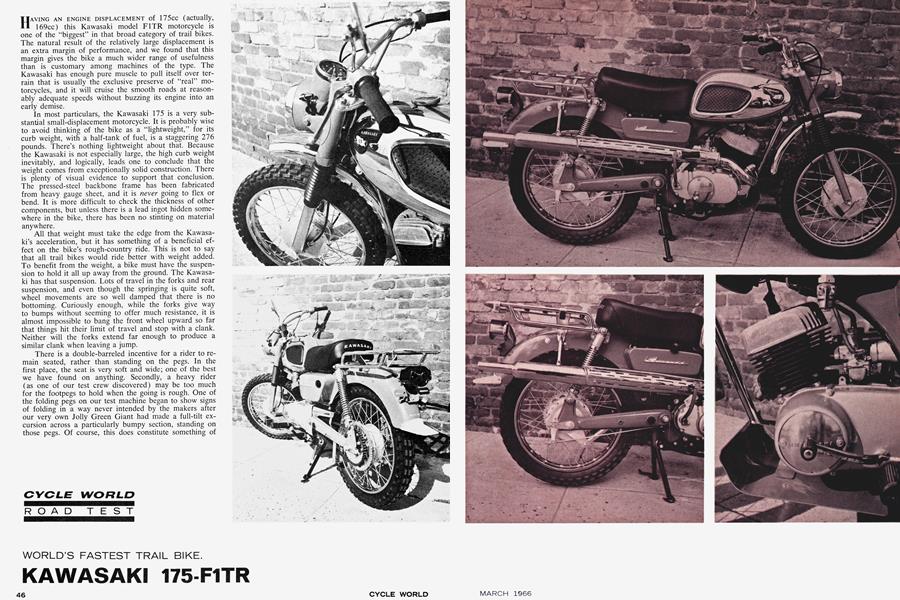

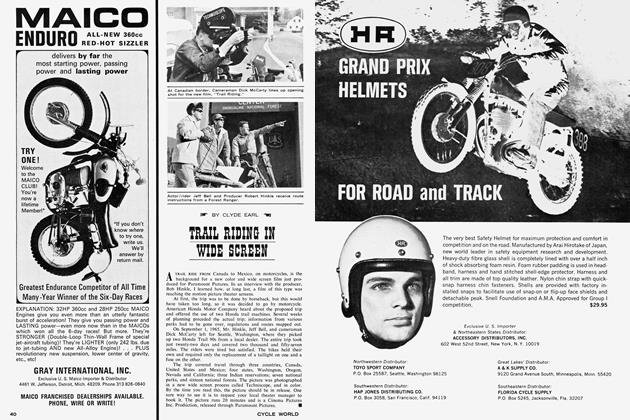

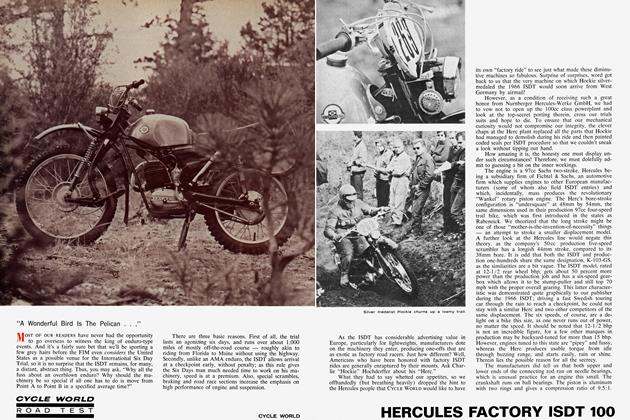

HAVING AN ENGINE DISPLACEMENT of 175cc (actually, 169cc) this Kawasaki model F1TR motorcycle is one of the "biggest" in that broad category of trail bikes. The natural result of the relatively large displacement is an extra margin of performance, and we found that this margin gives the bike a much wider range of usefulness than is customary among machines of the type. The Kawasaki has enough pure muscle to pull itself over terrain that is usually the exclusive preserve of "real" motorcycles, and it will cruise the smooth roads at reasonably adequate speeds without buzzing its engine into an early demise.

In most particulars, the Kawasaki 175 is a very sub stantial small-displacement motorcycle. It is probably wise to avoid thinking of the bike as a "lightweight," for its curb weight, with a half-tank of fuel, is a staggering 276 pounds. There's nothing lightweight about that. Because the Kawasaki is not especially large, the high curb weight inevitably, and logically, leads one to conclude that the weight comes from exceptionally solid construction. There is plenty of visual evidence to support that conclusion. The pressed-steel backbone frame has been fabricated from heavy gauge sheet, and it is never going to flex or bend. It is more difficult to check the thickness of other components, but unless there is a lead ingot hidden some where in the bike, there has been no stinting on material anywhere.

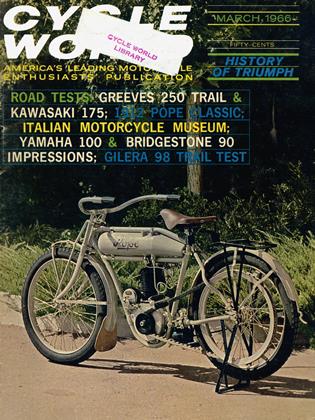

All that weight must take the edge from the Kawasa ki's acceleration, but it has something of a beneficial ef fect on the bike's rough-country ride. This is not to say that all trail bikes would ride better with weight added. To benefit from the weight, a bike must have the suspen sion to hold it all up away from the ground. The Kawasa ki has that suspension. Lots of travel in the forks and rear suspension, and even though the springing is quite soft, wheel movements are so well damped that there is no bottoming. Curiously enough, while the forks give way to bumps without seeming to offer much resistance, it is almost impossible to bang the front wheel upward so far that things hit their limit of travel and stop with a clank. Neither will the forks extend far enough to produce a similar clank when leaving a jump.

There is a double-barreled incentive for a rider to re main seated, rather than standing on the pegs. In the first place, the seat is very soft and wide; one of the best we have found on anything. Secondly, a heavy rider (as one of our test crew discovered) may be too much for the footpegs to hold when the going is rough. One of the folding pegs on our test machine began to show signs of folding in a way never intended by the makers after our very own Jolly Green Giant had made a full-tilt ex cursion across a particularly bumpy section, standing on those pegs. Of course, this does constitute something of an extreme test, and we did like the fact that the pegs were spring-loaded so that they snap back into their extended position.

Handlebars on trail bikes should be wide enough for good leverage, but a bit higher and narrower than what would be right for a pure scrambler — and that just about describes the Kawasaki’s bars. There are times when you could use more leverage, but most trailing types will not try to make the bike behave like a scrambler, and we know from experience that the wider bars are a hindrance when working through high brush and small trees. And, we also know that a bike with engine cases as wide as those of the Kawasaki is likely to present clearance problems down near ground-level. Ground clearance, in the usual sense, is adequate, and the exhaust pipe is mounted high on the bike’s side, but the whole assembly is so wide the rider sometimes feels almost as though he is riding a barrel.

One feature on the Kawasaki everyone will like is the “trail-sprocket” changeover arrangement. The normal, “street” sprocket is bolted securely to the wheel hub, but when not in use, the overlay sprocket is somewhat loosely located between the street sprocket and the wheel spokes. A set of springs, on the bolts that hold the sprockets together, hold the overlay sprocket out of the way when not in use. To set up for trail riding, you remove the chain, tighten the bolts (which pulls the big sprocket’s dished hub back over the smaller sprocket) and then add a short length to the chain. Reverse the process to get thhe cruising ratio back. No need to do anything about the rear wheel; it stays firmly in place.

The Kawasaki’s engine/transmission unit is totally orthodox. The engine has piston-controlled intake porting, and oil-in-the-fuel lubrication. It develops maximum power at only 7000 rpm, but the torque peak is up at 6000 rpm and for such a mild engine, it is surprisingly flat down at low crank speeds. Keep it turning more than 3000 rpm and do not exceed 7500. Below 3000 the power output is practically nil, and the engine runs completely out of air above 7500 rpm.

Part of the Kawasaki’s great weight must surely come from its electrical system. The battery is big enough to be used in an automobile. However, do not try to replace the stock battery with anything smaller. The engine has a “dyna-start” starter/generator unit, which is fixed right to the end of the crankshaft. Push the start button and it behaves as a starting motor. After the button is released it automatically becomes a generator. There being no reduction gears, a lot of oomph is required from the battery to get things turning; a small battery would never do the job.

Basically, the Kawasaki 175 is a very good motorcycle, and we liked it very much indeed. All it needs is a bit of lightening. And, of course, even without the lightening it is one of the very best “trail” bikes around — as well it might be, being much more nearly a “real” motorcycle than the sort of super-lightweight usually employed for trail riding. ■

KAWASAKI

F-1TR

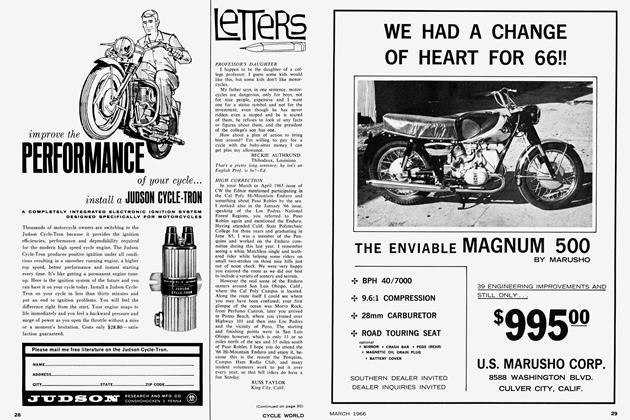

SPECIFICATIONS

$565

PERFcRMANCE