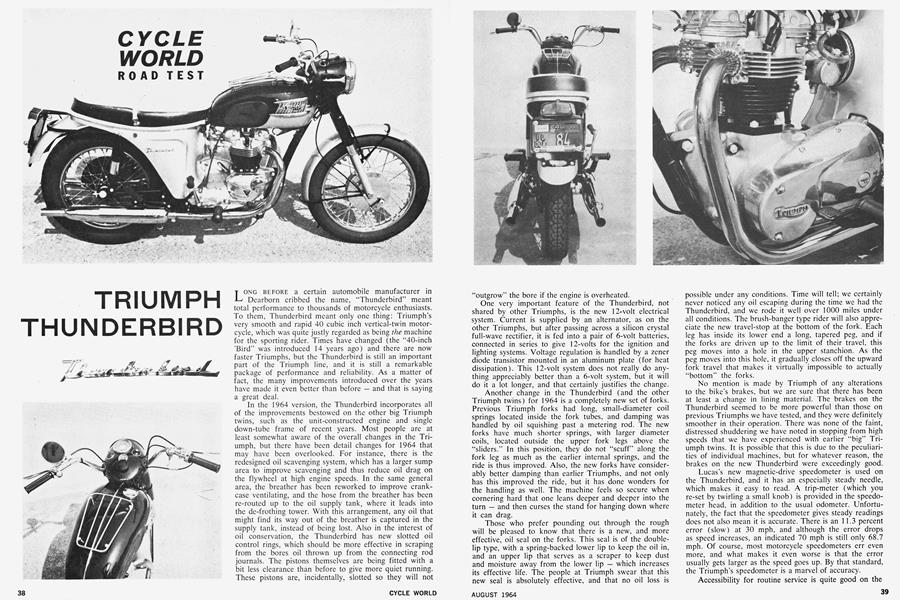

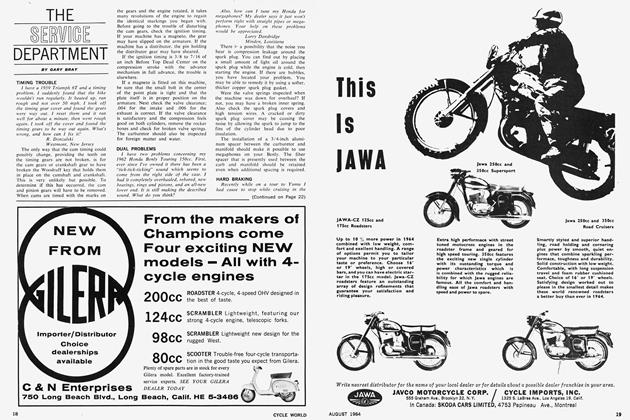

TRIUMPH THUNDERBIRD

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

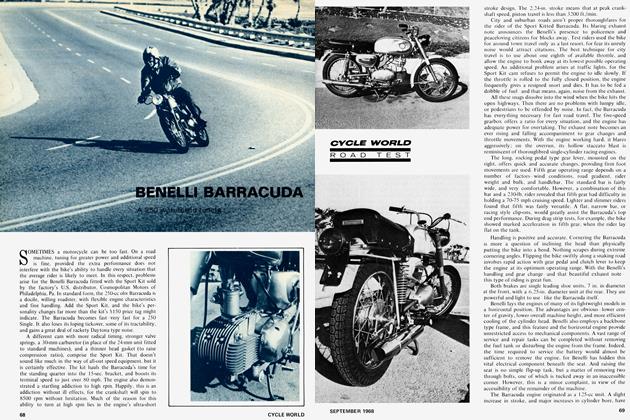

LONG BEFORE a certain automobile manufacturer in Dearborn cribbed the name, "Thunderbird" meant total performance to thousands of motorcycle enthusiasts. To them, Thunderbird meant only one thing: Triumph's very smooth and rapid 40 cubic inch vertical-twin motorcycle, which was quite justly regarded as being the machine for the sporting rider. Times have changed (the "40-inch 'Bird" was introduced 14 years ago) and there are now faster Triumphs, but the Thunderbird is still an important part of the Triumph line, and it is still a remarkable package of performance and reliability. As a matter of fact, the many improvements introduced over the years have made it even better than before — and that is saying a great deal.

In the 1964 version, the Thunderbird incorporates all of the improvements bestowed on the other big Triumph twins, such as the unit-constructed engine and single down-tube frame of recent years. Most people are at least somewhat aware of the overall changes in the Tri umph, but there have been detail changes for 1964 that may have been overlooked. For instance, there is the redesigned oil scavenging system, which has a larger sump area to improve scavenging and thus reduce oil drag on the flywheel at high engine speeds. In the same general area, the breather has been reworked to improve crank case ventilating, and the hose from the breather has been re-routed up to the oil supply tank, where it leads into the de-frothing tower. With this arrangement, any oil that might find its way out of the breather is captured in the supply tank, instead of being lost. Also in the interest of oil conservation, the Thunderbird has new slotted oil control rings, which should be more effective in scraping from the bores oil thrown up from the connecting rod journals. The pistons themselves are being fitted with a bit less clearance than before to give more quiet running. These pistons are, incidentally, slotted so they will not "outgrow" the bore if the engine is overheated.

One very important feature of the Thunderbird, not shared by other Triumphs, is the new 12-volt electrical system. Current is supplied by an alternator, as on the other Triumphs, but after passing across a silicon crystal full-wave rectifier, it is fed into a pair of 6-volt batteries, connected in series to give 12-volts for the ignition and lighting systems. Voltage regulation is handled by a zener diode transistor mounted in an aluminum plate (for heat dissipation). This 12-volt system does not really do anything appreciably better than a 6-volt system, but it will do it a lot longer, and that certainly justifies the change.

Another change in the Thunderbird (and the other Triumph twins) for 1964 is a completely new set of forks. Previous Triumph forks had long, small-diameter coil springs located inside the fork tubes, and damping was handled by oil squishing past a metering rod. The new forks have much shorter springs, with larger diameter coils, located outside the upper fork legs above the "sliders." In this position, they do not "scuff" along the fork leg as much as the earlier internal springs, and the ride is thus improved. Also, the new forks have considerably better damping than earlier Triumphs, and not only has this improved the ride, but it has done wonders for the handling as well. The machine feels so secure when cornering hard that one leans deeper and deeper into the turn — and then curses the stand for hanging down where it can drag.

Those who prefer pounding out through the rough will be pleased to know that there is a new, and more effective, oil seal on the forks. This seal is of the doublelip type, with a spring-backed lower lip to keep the oil in, and an upper lip that serves as a scraper to keep dust and moisture away from the lower lip — which increases its effective life. The people at Triumph swear that this new seal is absolutely effective, and that no oil loss is possible under any conditions. Time will tell; we certainly never noticed any oil escaping during the time we had the Thunderbird, and we rode it well over 1000 miles under all conditions. The brush-banger type rider will also appreciate the new travel-stop at the bottom of the fork. Each leg has inside its lower end a long, tapered peg, and if the forks are driven up to the limit of their travel, this peg moves into a hole in the upper stanchion. As the peg moves into this hole, it gradually closes off the upward fork travel that makes it virtually impossible to actually "bottom" the forks.

No mention is made by Triumph of any alterations to the bike's brakes, but we are sure that there has been at least a change in lining material. The brakes on the Thunderbird seemed to be more powerful than those on previous Triumphs we have tested, and they were definitely smoother in their operation. There was none of the faint, distressed shuddering we have noted in stopping from high speeds that we have experienced with earlier "big" Triumph twins. It is possible that this is due to the peculiarities of individual machines, but for whatever reason, the brakes on the new Thunderbird were exceedingly good.

Lucas's new magnetic-drive speedometer is used on the Thunderbird, and it has an especially steady needle, which makes it easy to read. A trip-meter (which you re-set by twirling a small knob) is provided in the speedometer head, in addition to the usual odometer. Unfortunately, the fact that the speedometer gives steady readings does not also mean it is accurate. There is an 11.3 percent error (slow) at 30 mph, and although the error drops as speed increases, an indicated 70 mph is still only 68.7 mph. Of course, most motorcycle speedometers err even more, and what makes it even worse is that the error usually gets larger as the speed goes up. By that standard, the Triumph's speedometer is a marvel of accuracy.

Accessibility for routine service is quite good on the Thunderbird. The spark plugs are not buried under the tank, and the ignition points can be reached by removing a small cover at the end of the exhaust cam. Water can be added to the batteries merely by flipping up the hinged seat, which also exposes most of the electricals and the shelf where the tool kit is kept. Also, the filler cap for the oil supply tank is under the seat. Needless to say, this arrangement is somewhat better than having to unscrew knobs and remove covers to get at these items.

All the oil drain plugs for crankcase, transmission and primary drive case are easily reached, and those who have struggled with draining the oil supply tank, which required the removal of a plug to which the oil outlet was fitted, will be delighted to hear that there is now a separate oil drain plug — easily reached on all the Triumphs but the Thunderbird. The enclosure in front of the rear wheel, which keeps the engine and rider so clean and neat, completely covers the oil tank, and it must be unbolted (3 bolts, 2 screws and a knob) before the drain plug is within reach. We rather imagine that many Thunderbird buyers will elect to simply leave the enclosure in the garage; the full fender is there anyway. This would leave the air cleaner completely exposed (and it is a very good, fibertype air cleaner, by the way) but that will not reduce its effectiveness.

The best of the Thunderbird's many qualities (performance, economy, reliability, etc.) is that it is such a civilized motorcycle. The mildly tuned engine is phenomenally smooth, because of the single carburetor and low, 7.5:1 compression ratio, and it will idle and pull at low speeds in a way that makes it a particular pleasure to ride in city traffic. And, of course, it is also capable of boring down the open highway at a most impressive rate.

We simply cannot find fault with the ride, or riding position, or controls. Everything operates with great ease and precision, and the seat, pegs and handlebars suited us perfectly. Actually, we suppose the bars are a bit too high for high-speed cruising, and a bit low for riding in town, but they constitute a compromise that is not likely to be improved upon so long as the Thunderbird is used in all kinds of riding.

It is impossible to say too much good about the Thunderbird's starting characteristics. Hot or cold, the engine would almost invariably come to life with a single kick and not a particularly vigorous kick at that. No special starting "combination" is required, either; the en-' gine has an automatic advance/retard on the ignition (as do many others) and so when it is warm, the rider need only tweak the throttle a hair and crank it through. When cold, the drill is the same except that the choke is used. There is no need to "tickle" the carburetor float.

In all, the Thunderbird impressed us as being very much the gentleman's motorcycle. It starts too easily to force one to work up a sweat, and it proceeds to its destination smoothly and quietly. There is ample performance on tap, and while it is not much faster than some of the hotter small-displacement bikes, it does what it does without a lot of gear-stirring and threshing of the engine. We return the Triumph Thunderbird with reluctance, for it has been as pleasant a motorcycle as ever offered to us for test. May Triumph sell a million of them.

TRIUMPH

THUNDERBIRD

SPECIFICATIONS

$ 1,066