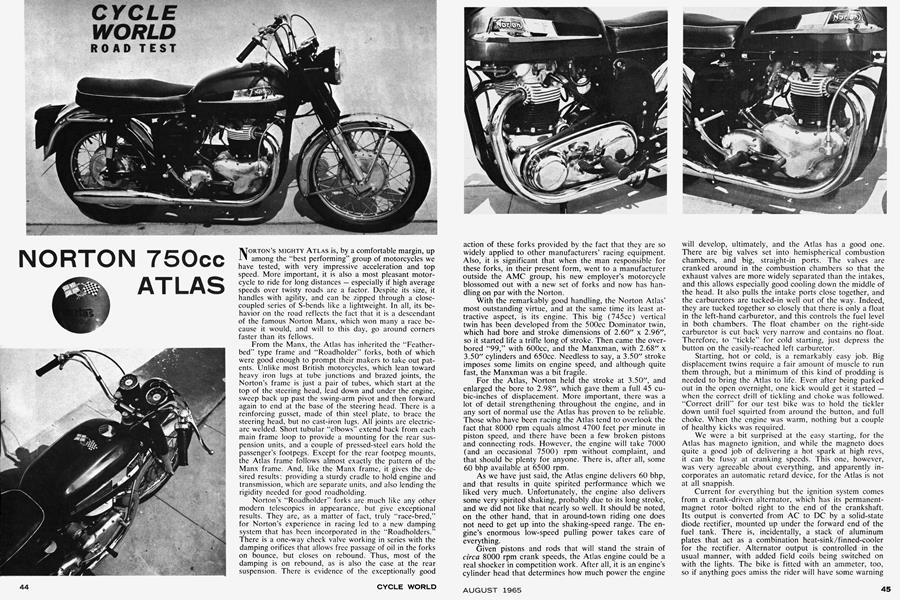

NORTON 750cc ATLAS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

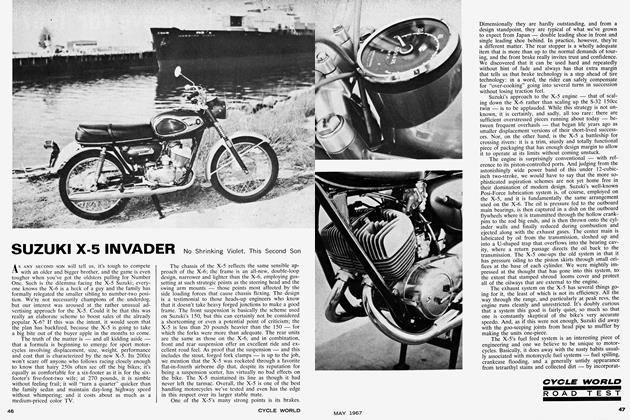

NORTON'S MIGHTY ATLAS is, by a comfortable margin, up among the "best performing" group of motorcycles we have tested, with very impressive acceleration and top speed. More important, it is also a most pleasant motorcycle to ride for long distances — especially if high average speeds over twisty roads are a factor. Despite its size, it handles with agility, and can be zipped through a closecoupled series of S-bends like a lightweight. In all, its behavior on the road reflects the fact that it is a descendant of the famous Norton Manx, which won many a race because it would, and will to this day, go around corners faster than its fellows.

From the Manx, the Atlas has inherited the "Featherbed" type frame and "Roadholder" forks, both of which were good enough to prompt their makers to take out patents. Unlike most British motorcycles, which lean toward heavy iron lugs at tube junctions and brazed joints, the Norton's frame is just a pair of tubes, which start at the top of the steering head, lead down and under the engine, sweep back up past the swing-arm pivot and then forward again to end at the base of the steering head. There is a reinforcing gusset, made of thin steel plate, to brace the steering head, but no cast-iron lugs. All joints are electricarc welded. Short tubular "elbows" extend back from each main frame loop to provide a mounting for the rear suspension units, and a couple of pressed-steel ears hold the passenger's footpegs. Except for the rear footpeg mounts, the Atlas frame follows almost exactly the pattern of the Manx frame. And, like the Manx frame, it gives the desired results: providing a sturdy cradle to hold engine and transmission, which are separate units, and also lending the rigidity needed for good roadholding.

Norton's "Roadholder" forks are much like any other modern telescopies in appearance, but give exceptional results. They are, as a matter of fact, truly "race-bred," for Norton's experience in racing led to a new damping system that has been incorporated in the "Roadholders." There is a one-way check valve working in series with the damping orifices that allows free passage of oil in the forks on bounce, but closes on rebound. Thus, most of the damping is on rebound, as is also the case at the rear suspension. There is evidence of the exceptionally good action of these forks provided by the fact that they are so widely applied to other manufacturers' racing equipment. Also, it is significant that when the man responsible for these forks, in their present form, went to a manufacturer outside the AMC group, his new employer's motorcycle blossomed out with a new set of forks and now has handling on par with the Norton.

With the remarkably good handling, the Norton Atlas' most outstanding virtue, and at the same time its least attractive aspect, is its engine. This big (745cc) vertical twin has been developed from the 500cc Dominator twin, which had bore and stroke dimensions of 2.60" x 2.96", so it started life a trifle long of stroke. Then came the overbored "99," with 600cc, and the Manxman, with 2.68" x 3.50" cylinders and 650cc. Needless to say, a 3.50" stroke imposes some limits on engine speed, and although quite fast, the Manxman was a bit fragile.

For the Atlas, Norton held the stroke at 3.50", and enlarged the bore to 2.98", which gave them a full 45 cubic-inches of displacement. More important, there was a lot of detail strengthening throughout the engine, and in any sort of normal use the Atlas has proven to be reliable. Those who have been racing the Atlas tend to overlook the fact that 8000 rpm equals almost 4700 feet per minute in piston speed, and there have been a few broken pistons and connecting rods. However, the engine will take 7000 (and an occasional 7500) rpm without complaint, and that should be plenty for anyone. There is, after all, some 60 bhp available at 6500 rpm.

As we have just said, the Atlas engine delivers 60 bhp, and that results in quite spirited performance which we liked very much. Unfortunately, the engine also delivers some very spirited shaking, probably due to its long stroke, and we did not like that nearly so well. It should be noted, on the other hand, that in around-town riding one does not need to get up into the shaking-speed range. The engine's enormous low-speed pulling power takes care of everything.

Given pistons and rods that will stand the strain of circa 8000 rpm crank speeds, the Atlas engine could be a real shocker in competition work. After all, it is an engine's cylinder head that determines how much power the engine will develop, ultimately, and the Atlas has a good one. There are big valves set into hemispherical combustion chambers, and big, straight-in ports. The valves are cranked around in the combustion chambers so that the exhaust valves are more widely separated than the intakes, and this allows especially good cooling down the middle of the head. It also pulls the intake ports close together, and the carburetors are tucked-in well out of the way. Indeed, they are tucked together so closely that there is only a float in the left-hand carburetor, and this controls the fuel level in both chambers. The float chamber on the right-side carburetor is cut back very narrow and contains no float. Therefore, to "tickle" for cold starting, just depress the button on the easily-reached left carburetor.

Starting, hot or cold, is a remarkably easy job. Big displacement twins require a fair amount of muscle to run them through, but a minimum of this kind of prodding is needed to bring the Atlas to life. Even after being parked out in the open overnight, one kick would get it started — when the correct drill of tickling and choke was followed. "Correct drill" for our test bike was to hold the tickler down until fuel squirted from around the button, and full choke. When the engine was warm, nothing but a couple of healthy kicks was required.

We were a bit surprised at the easy starting, for the Atlas has magneto ignition, and while the magneto does quite a good job of delivering a hot spark at high revs, it can be fussy at cranking speeds. This one, however, was very agreeable about everything, and apparently incorporates an automatic retard device, for the Atlas is not at all snappish.

Current for everything but the ignition system comes from a crank-driven alternator, which has its permanentmagnet rotor bolted right to the end of the crankshaft. Its output is converted from AC to DC by a solid-state diode rectifier, mounted up under the forward end of the fuel tank. There is, incidentally, a stack of aluminum plates that act as a combination heat-sink/finned-cooler for the rectifier. Alternator output is controlled in the usual manner, with added field coils being switched on with the lights. The bike is fitted with an ammeter, too, so if anything goes amiss the rider will have some warning before the battery goes flat or begins to smoke. The finish is good throughout most of the machine. The frame is black-enameled; the big, stylish fuel tank is a deep, glorious metallic ruby, and the fenders are chromed steel. Aluminum alloy parts around the bike, like the front brake drum and fork sliders, are polished. But, apart from the brightwork on the primary case, the engine is not very impressive looking. The castings are crude, and there are too many lengths of piping and wire leading thither and yon. Very likely, none of this has any effect whatever on the engine's performance, but it is at odds with the trend toward clean engine exteriors. Criticisms of the engine's finish and long stroke notwithstanding, we liked everything about the Atlas but the rather excessive vibration (which is not really any worse than any other big-displacement twin at that). We will say again that it is a fantastically good-handling motorcycle, and add the comment that it is also one of the bestriding. The ride does not have that ostentatious sponginess of some "luxury" bikes; it is a little more firm, and infinitely better controlled. Riding pleasure is further enhanced by the bags of power available anytime just by turning the tap. The Atlas may not rev too freely, but it pulls so strongly from 2000 to 6500 rpm that no one with any sense will care. The transmission is a marvel of smooth shifting, and its ratios are staged so that 3rd would make a marvelous passing-gear — but you don't need it. Simply twist the wick and the bike moves away like the rocket for which it was presumably named. •

NORTON

750 ATLAS

$1244

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue