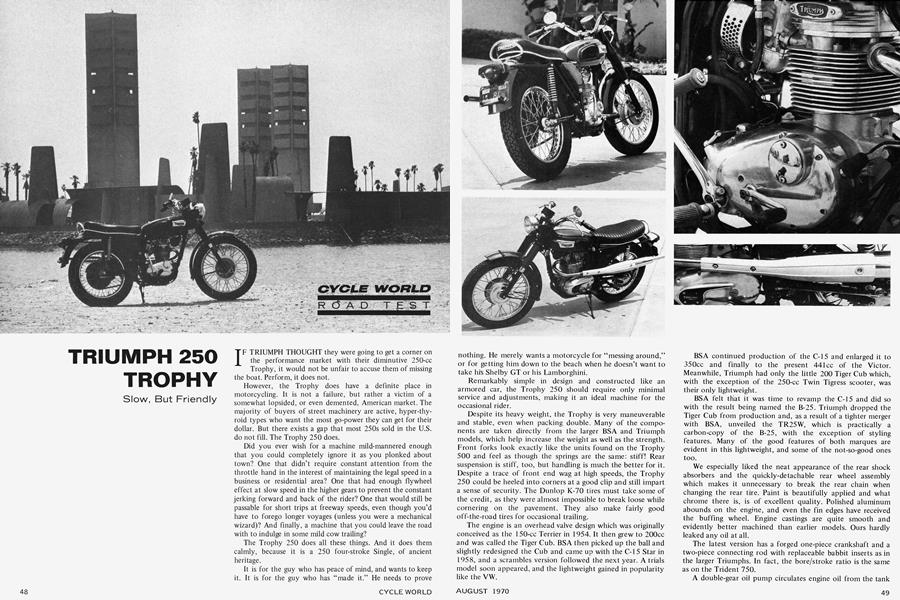

TRIUMPH 250 TROPHY

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Slow, But Friendly

IF TRIUMPH THOUGHT they were going to get a corner on the performance market with their diminutive 250-cc Trophy, it would not be unfair to accuse them of missing the boat. Perform, it does not.

However, the Trophy does have a definite place in motorcycling. It is not a failure, but rather a victim of a somewhat lopsided, or even demented, American market. The majority of buyers of street machinery are active, hyper-thyroid types who want the most go-power they can get for their dollar. But there exists a gap that most 250s sold in the U.S. do not fill. The Trophy 250 does.

Did you ever wish for a machine mild-mannered enough that you could completely ignore it as you plonked about town? One that didn’t require constant attention from the throttle hand in the interest of maintaining the legal speed in a business or residential area? One that had enough flywheel effect at slow speed in the higher gears to prevent the constant jerking forward and back of the rider? One that would still be passable for short trips at freeway speeds, even though you’d have to forego longer voyages (unless you were a mechanical wizard)? And finally, a machine that you could leave the road with to indulge in some mild cow trading?

The Trophy 250 does all these things. And it does them calmly, because it is a 250 four-stroke Single, of ancient heritage.

It is for the guy who has peace of mind, and wants to keep it. It is for the guy who has “made it.” He needs to prove nothing. He merely wants a motorcycle for “messing around,” or for getting him down to the beach when he doesn’t want to take his Shelby GT or his Lamborghini.

Remarkably simple in design and constructed like an armored car, the Trophy 250 should require only minimal service and adjustments, making it an ideal machine for the occasional rider.

Despite its heavy weight, the Trophy is very maneuverable and stable, even when packing double. Many of the components are taken directly from the larger BSA and Triumph models, which help increase the weight as well as the strength. Front forks look exactly like the units found on the Trophy 500 and feel as though the springs are the same: stiff! Rear suspension is stiff, too, but handling is much the better for it. Despite a trace of front end wag at high speeds, the Trophy 250 could be heeled into corners at a good clip and still impart a sense of security. The Dunlop K-70 tires must take some of the credit, as they were almost impossible to break loose while cornering on the pavement. They also make fairly good off-the-road tires for occasional trailing.

The engine is an overhead valve design winch was originally conceived as the 150-cc Terrier in 1954. It then grew to 200cc and was called the Tiger Cub. BSA then picked up the ball and slightly redesigned the Cub and came up with the C-15 Star in 1958, and a scrambles version followed the next year. A trials model soon appeared, and the lightweight gained in popularity like the VW.

BSA continued production of the C-15 and enlarged it to 350cc and finally to the present 441 cc of the Victor. Meanwhile, Triumph had only the little 200 Tiger Cub which, with the exception of the 250-cc Twin Tigress scooter, was their only liglitweight.

BSA felt that it was time to revamp the C-15 and did so with the result being named the B-25. Triumph dropped the Tiger Cub from production and, as a result of a tighter merger with BSA, unveiled the TR25W, which is practically a carbon-copy of the B-25, with the exception of styling features. Many of the good features of both marques are evident in this lightweight, and some of the not-so-good ones too.

We especially liked the neat appearance of the rear shock absorbers and the quickly-de tacha ble rear wheel assembly which makes it unnecessary to break the rear chain when changing the rear tire. Paint is beautifully applied and what chrome there is, is of excellent quality. Polished aluminum abounds on the engine, and even the fin edges have received the buffing wheel. Engine castings are quite smooth and evidently better machined than earlier models. Ours hardly leaked any oil at all.

The latest version has a forged one-piece crankshaft and a two-piece connecting rod with replaceable babbit inserts as in the larger Triumphs. In fact, the bore/stroke ratio is the same as on the Trident 750.

A double-gear oil pump circulates engine oil from the tank through the engine and passes through two rather coarse strainers, one in the bottom of the tank and the other in the sump by the pump. Oil for the overhead valve rocker mechanism is taken from a bleed tube in the return oil line. Both the transmission and the primary chaincase have their own oil supplies, with the primary’s being used to lubricate the rear chain.

The engine is somewhat noisy, with considerable valve clatter as in earlier models. This is due to the fact that there are no ribs cast between the fins to help deaden the racket. But, ribs would be less attractive than no ribs, and one gets accustomed to the din rather quickly. It made all of us nostalgic, but we know of one tester who would put plastic buttons between his fins!

A rather sporty camshaft lifts the valves using relatively short pushrod assemblies which terminate into rocker arms with no adjusting screws. The rocker arm spindles are eccentric, and adjustment is accomplished by rotating them slightly until the correct valve clearance is obtained, without the need for the slightly heavier screw and nut arrangement found on most four cycles. The little engine revs quite happily over the 8000-rpm mark without valve float, but it must be kept revving to get much power out of it. It is happy enough when pottering about town in the higher gears, but power is lacking.

Four-speed gearboxes are practically passe these days where five-and six-speeders abound, but the Trophy’s gear ratios are so well placed that more gears really aren’t necessary. Shifting was quick and positive, neutral easy to find. Clutch action is light, thanks to the worm-gear disengaging mechanism, and shocks from the power impulses of the engine are effectively damped by rubber discs in the clutch hub. The clutch stood up well under the fairly heavy slipping it was subjected to while we were trying out the off-roadability. This was where the stiff suspension really paid off. It was practically impossible to bottom the forks and the wheels were able to follow the ground irregularities quite well. We did feel that a steering damper would be beneficial for this type of going, however.

Controls are well laid out, in British fashion, with the shift on the right and rear brake on the left. Handlebars are just right for the type of riding most Americans do, but were a trifle high for high-speed riding. The throttle is a quick-acting unit which requires only a quarter-turn to open fully. Headlight dimmer switch and horn button are located on the left handlebar, conveniently close to the rider’s thumb. The headlight switch nestles between the high-beam indicator and the oil pressure warning lights in the center of the headlight.

Starting was a simple matter, even on cool mornings. Simply turn on the gas valve, tickle the carburetor until the float bowl overflows, and give the kickstarter a deliberate prod. It rarely took more than two kicks to get it going and only a minute or so before it would run smoothly. Lighting was excellent, and all the electrics performed splendidly. Even the horn was audible.

Plonking around town was a delight. With more than adequate brakes and easy-to-operate controls, threading one’s way through 5 o’clock traffic was child’s play. Once on the freeway, however, it was necessary to keep the engine buzzing to get with the traffic. Muffling is quite good with a silencer as large as on the 650 Triumph twins, but the heat guard was very uncomfortable for the passenger and looked rather out of place. It is made of fiberglass(l) and is a metalflake silver color, which didn’t really go with any other color on the machine.

A nice feature was the oil pressure warning light on the headlight, the sending unit for which was located on the right-hand side near the front of the crankcase. As soon as the check ball lifts off its seat, the light extinguishes, but with all the chrome on the headlight, it was difficult to tell whether it was burning or not because of the sun’s reflection.

The blending of so many big motor components is done rather skillfully, but we were stumped as to why the front spokes should be one-third again as large as the rear spokes and why the springing should be so stiff. There was no provision for a center stand, either.

We all enjoyed riding the Trophy 250 and would like to see more four-stroke Singles in production. There’s something about riding one that you can’t forget.

TRIUMPH

250 TROPHY

SPECIFICATIONS

$755

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

August 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

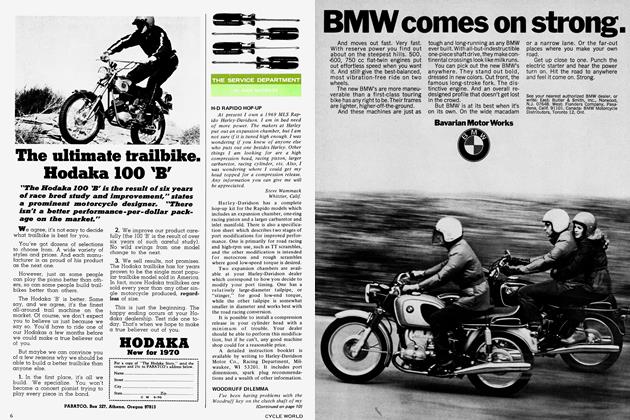

DepartmentsThe Service Department

August 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

August 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Features

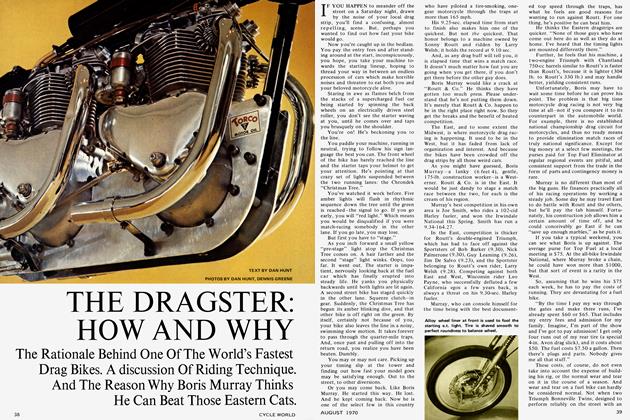

Special FeaturesThe Dragster: How And Why

August 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesThe Princess & the Peasant

August 1970 By Cecil P. Mack