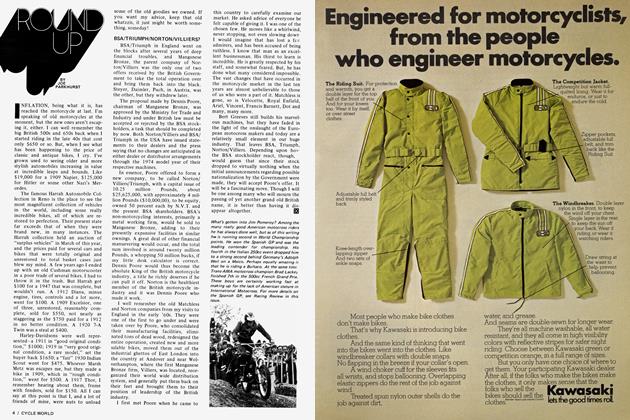

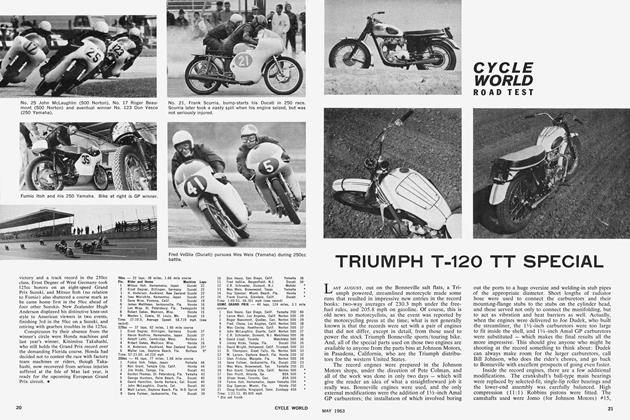

MOTOCROSSERS: KAWASAKI STYLE

Cycle World Road Test

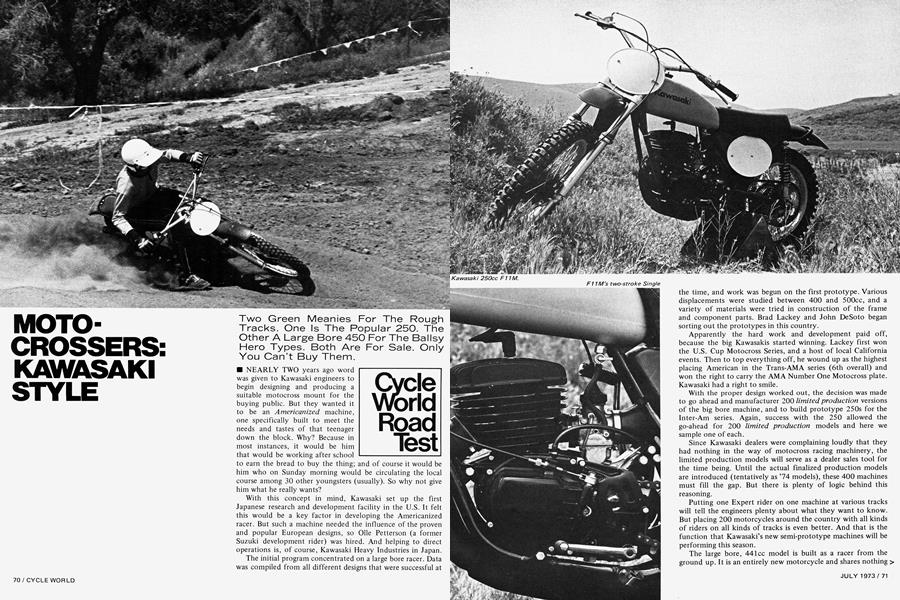

Two Green Meanies For The Rough Tracks. One Is The Popular 250. The Other A Large Bore 450 For The Ballsy Hero Types. Both Are For Sale. Only You Can't Buy Them.

NEARLY TWO years ago word was given to Kawasaki engineers to begin designing and producing a suitable motocross mount for the buying public. But they wanted it to be an Americanized machine, one specifically built to meet the needs and tastes of that teenager down the block. Why? Because in most instances, it would be him that would be working after school to earn the bread to buy the thing; and of course it would be him who on Sunday morning would be circulating the local course among 30 other youngsters (usually). So why not give him what he really wants?

With this concept in mind, Kawasaki set up the first Japanese research and development facility in the U.S. It felt this would be a key factor in developing the Americanized racer. But such a machine needed the influence of the proven and popular European designs, so Olle Petterson (a former Suzuki development rider) was hired. And helping to direct operations is, of course, Kawasaki Heavy Industries in Japan.

The initial program concentrated on a large bore racer. Data was compiled from all different designs that were successful at the time, and work was begun on the first prototype. Various displacements were studied between 400 and 500cc, and a variety of materials were tried in construction of the frame and component parts. Brad Lackey and John DeSoto began sorting out the prototypes in this country.

Apparently the hard work and development paid off, because the big Kawasakis started winning. Lackey first won the U.S. Cup Motocross Series, and a host of local California events. Then to top everything off, he wound up as the highest placing American in the Trans-AM A series (6th overall) and won the right to carry the AMA Number One Motocross plate. Kawasaki had a right to smile.

With the proper design worked out, the decision was made to go ahead and manufacturer 200 limited production versions of the big bore machine, and to build prototype 250s for the Inter-Am series. Again, success with the 250 allowed the go-ahead for 200 limited production models and here we sample one of each.

Since Kawasaki dealers were complaining loudly that they had nothing in the way of motocross racing machinery, the limited production models will serve as a dealer sales tool for the time being. Until the actual finalized production models are introduced (tentatively as ’74 models), these 400 machines must fill the gap. But there is plenty of logic behind this reasoning.

Putting one Expert rider on one machine at various tracks will tell the engineers plenty about what they want to know. But placing 200 motorcycles around the country with all kinds of riders on all kinds of tracks is even better. And that is the function that Kawasaki’s new semi-prototype machines will be performing this season.

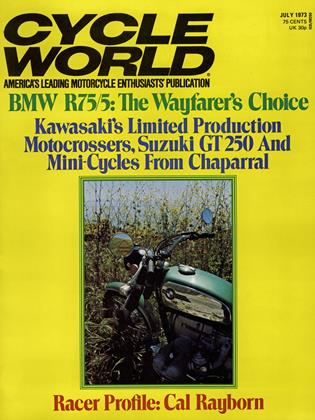

The large bore, 441cc model is built as a racer from the ground up. It is an entirely new motorcycle and shares nothing > with any of the present or past Kawasaki regular production models. The 250, however, is an Fl 1 Enduro offshoot, and its basis is a standard production model.

Chrome moly tubing is used on the single toptube, single downtube 450 frame, while mild steel is found in the 250. The Fll features a double downtube arrangement and geometry is the same as the Fll Enduro. To alter steering characteristics, different triple-clamps are used.

Both models use tubular swinging arms mounted in bronze bushings with ample gusseting at stress points. In fact, Kawasaki paid particular attention to frame strength, with careful consideration for weight.

Special Daido aluminum alloy wheels are found on both the 250 and 450. The wheels are very similar to those used on the Honda XL250 and are noted for exceptional strength. An

added benefit of the design is that it doesn’t allow the build-up of mud and debris, which can add about 5 lb. per wheel during a muddy event. And that is 10 lb. of unsprung weight.

Conventional practice now finds most 250 sized machines running 3.00-21-in. rubber at the front, with a 4.00-18-in. on the rear. The F11M is no exception. But to cope with the additional horsepower and torque of the 450, Kawasaki mounts a giant 4.60-18-in. tire to the rear of the monster, and you should see the dirt fly when that engine gets turned on.

Hubs on both machines are very similar, but magnesium is used on the 450 as opposed to aluminum on the smaller machine. Incidentally, this is the only magnesium used on either bike, a far cry from Brad Lackey’s prototype of last year.

One would guess that the 450 would be somewhat heavier than its smaller brother, but that isn’t the case at all. The 250 is actually 8 lb. heavier, and Kawasaki feels that this is due to the fact that the Fl 1M is basically a production model. Design any machine from the beginning as a racer and it’s bound to be lighter.

Suspension is generally first rate. We experienced some bottoming of the forks when we made improper landings off jumps, but it didn’t affect handling and at no time was it disconcerting to the riders. On the especially hard, bumpy downhills at Saddleback Park, the fork’s damping and rebound control amazed us. Both machines felt equal in this respect, a surprise since the F11M and F12M use different suspension components at both ends.

The Kayaba shocks on the 450 use the increasingly popular oil reservoir which effectively carries away the fluid heat build-up. This has long been a problem with shocks that work so hard on a rough track, and only recently have engineers come up with a solution. The people at Kawasaki R&D tell us that the Kayaba shocks also make good hammers when they’re worn out, and if you note the accompanying photographs you’ll see why!

Shocks on the 250 are more conventional, which may be an indication as to just how hard that 450 is on component parts. Shock units on both models hold two sets of progressively wound springs, and rates seemed ideal for the several different weights of our test riders.

Okay, so far we’ve seen some basics on what are reportedly pretty trick machines. But if you’re waiting to see how exotic the 250 and 450 become, you’ll be disappointed. Kawasaki’s new motocrossers are not exotic. They are basic simplicity.

The Fl 1 engine unit is changed substantially over the stock counterpart found in the Enduro, but this is done primarily through the substitution of parts more suited for motocross events. Both the head and cylinder are different, though the square 68x68mm bore/stroke dimensions remain. Outer side cases are new, as well, to reduce both weight and width of the engine. This made it necessary to design a new clutch actuating mechanism, but inside the clutch remains as before.

Horsepower has been upped from 23.5 at 6000 to 29.5 at 7500. The increase has come about through the use of a larger (32mm) Mikuni carburetor and a jump in compression from 7:1 to 8:1. Add a hotter ignition and a silenced expansion chamber and you suddenly have an engine ready for competition. Alter the transmission ratios and the package is nearly complete.

The 450 engine went through many design changes before a definite displacement size was decided upon. There also was an enormous amount of experimentation with porting, flywheel weights, and other minor differences. The final result produces 38 of the most tractable horsepower we have experienced in quite some time.

The 450, like the 250, is simplicity in engine design. A pressed together crank rides in ball bearing main bearings, and rollers support the big end of the steel connecting rod. A wrist pin riding on needle bearings holds the two-ring aluminum piston, which rides in a cast-in iron alloy cylinder liner. And what could be more simple than straightforward four-port design? No trick transfer ports here. Kawasaki says, “If the engine produces enough power with four ports, why have any more?”

The seat of the pants impression lets you know that both of these limited production Kawasakis have enough power to get the job done.

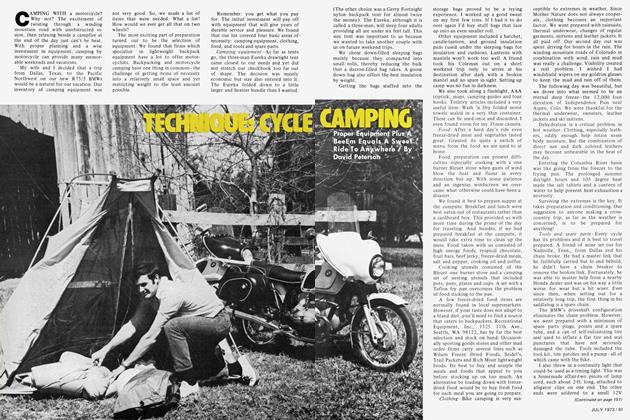

Seating position should be ideal for riders of average size. The seat allows for fore and aft movement of the rider, and the fuel tank doesn’t interfere with the knees. Sitting or standing, the rider is comfortable. Both machines are identical in these respects. Footpeg and handlebar positioning are close to perfect.

Since the models are to be produced in a limited supply, Kawasaki will be trying different types of control levers and related items. For example, our 450 test model featured Uni plastic clutch and brake levers, as well as a “Lexan” brake pedal. The 250 used aluminum levers and pedals instead. There seems to be no set rule in this respect.

Plastic is again used in the fuel tanks and fenders. It will take a pretty severe crash to damage any of these items. The fenders on the 450 were made in the U.S. by A&A, while the units fitted to the 250 were made in Japan. Though a couple of small parts on the machines are produced in the U.S., both the F11M and F12M are manufactured in Japan in their entirety.

Primary kick starting is a feature on both motorcycles, and one or two kicks is all that is necessary to bring either engine to life.

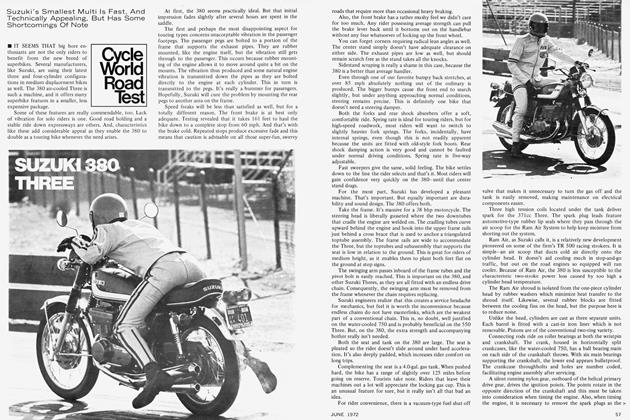

KAWASAKI

F11M

MOTOCROSSERS

F12M

The gearboxes don't seem to care whether or not you make use of the robust clutch assemblies, and that is a help in the heat of competition. If a gear was missed, it was usually our fault, not the transmission's.

By far the easiest machine to ride was the 450, simply because you could leave it in just about any one gear and circulate the course. But we doubt there are many riders capable of making use of all that power and torque, which seems like it starts at zero rpm and goes from there. It was quite easy to find third gear and race the entire Saddleback course at a fair clip. We were amazed. We have ridden several big bore MXers in the past, but none have had the controllable power of the Kawasaki Fl 2M.

It is obvious that the Kawasaki people devoted plenty of time to the 250, as well. For a racer with this engine size, the power band is quite broad. The rider finds that he can concentrate on items other than if he's in precisely the right gear at the right time.

Both machines tend to handle better under power, and if you're the type of rider that likes to ride WFO, these Kawasakis are just what you're looking for. Slide one into a corner at half pace, and you'll fight it a bit. But take the same turn full bore and only your nerves get a workout.

Select dealers all over the country will soon be getting the new Kawasaki 250 and 450 racers. They in turn will select who gets to ride one in competition. There is no doubt in our minds that either machine is capable of doing the job. If you'd like one, better get in line now....