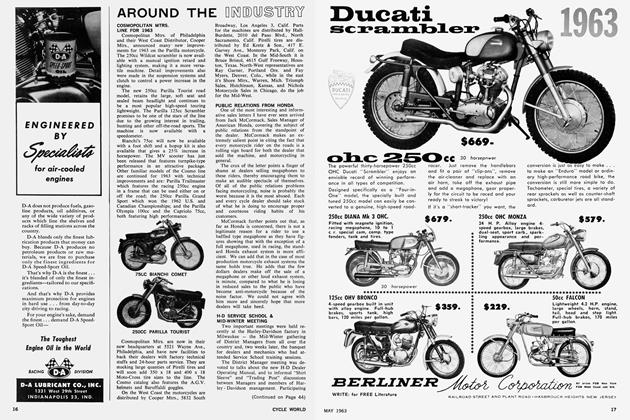

TRIUMPH T-120 TT SPECIAL

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

LAST AUGUST, out on the Bonneville salt flats, a Triumph powered, streamlined motorcycle made some runs that resulted in impressive new entries in the record books: two-way averages of 230.3 mph under the free-fuel rules, and 205.8 mph on gasoline. Of course, this is old news to motorcyclists, as the event was reported by the motorcycling press at the time; what is not generally known is that the records were set with a pair of engines that did not differ, except in detail, from those used to power the stock Triumph Bonneville sports/touring bike. And, all of the special parts used on those two engines are available to anyone from the parts bins at Johnson Motors, in Pasadena, California, who are the Triumph distributors for the western United States.

The record engines were prepared in the Johnson Motors shops, under the direction of Pete Colman, and all of the work was done in only two days - which will give the reader an idea of what a straightforward job it really was. Bonneville engines were used, and the only external modifications were the addition of 1½-inch Amal GP carburetors; the installation of which involved boring out the ports to a huge oversize and welding-in stub pipes of the appropriate diameter. Short lengths of radiator hose were used to connect the carburetors and their mounting-flange stubs to the stubs on the cylinder head, and these served not only to connect the manifolding, but to act as vibration and heat barriers as well. Actually, when the engines were delivered to Joe Dudek, who built the streamliner, the 1½-inch carburetors were too large to fit inside the shell, and 1¼-inch Ama! GP carburetors were substituted - which makes the final results all the more impressive. This should give anyone who might be shooting at the record something to think about: Dudek can always make room for the larger carburetors, call Bill Johnson, who does the rider's chores, and go back to Bonneville with excellent prospects of going even faster.

Inside the record engines, there are a few additional modifications. The crankshaft's ball-type main bearings were replaced by selected-fit, single-lip roller bearings and the lower-end assembly was carefully balanced. High compression (11: 1) Robbins pistons were fitted. The camshafts used were Jomo (for Johnson Motors) #15, which in conjunction with Triumph's E4040 tappets, give valve timings of 41° BTC - 71° ABC for the intakes and 71° BBC - 410 ATC for the exhausts. The intake valves were Jomo's 15/8-inch racing replacements, and these were installed on seats that had been trimmed to give the greatest effective diameter. Other valve-gear modifications were the polishing and lightening of the valve rockers, the use of lightweight pushrods (from the "C" range engines) and the installation of Jomo pro gressive-rate valve springs.

The only modification made in the interest of reli ability (which the Triumph has, in full measure, as it comes from the factory) was the addition of a tube that carries oil from the pressure-regulator bypass back to the oil tank. In the stock engine, this oil is dumped into the engine sump and picked up by the scavenging pump, and that arrangement works very well. However, at sustained high engine speeds, when a lot of oil is being bypassed (due to the great quantities of oil being pumped), the sump tends to load a little, and the re-routing of bypassed oil eases the task of the sump-scavenging pump.

A true measure of the reliability of this power unit is the fact that it did its job with a minimum of fuss and a maximum of reliability. Over 17 runs were made down the 9-mile stretch of salt at speeds well over 200 mph. Really though, this is little more than could have rea sonably been expected. The same engine is being used for TT racing all over the country, and Triumphs win with monotonous regularity - and you can't do that un less you finish a race with a healthy engine.

A newer, and slightly improved, version of the engines used to set the record powers the 1963 Triumph Bonne ville special - the machine that is the main subject of this report. It follows the long-time Triumph layout, but has a unit-constructed crank and transmission casing -and other detail changes.

Bore and stroke dimensions remain unchanged, but the crankshaft and flywheel, and the main bearing layout, have been improved. Previously, the crank was carried in one ball (on the drive side) and one plain bearing, but heavy-duty ball bearings are now used on both sides. "H" section, aluminum-alloy connecting rods are again fea tured, and these have shell - type, replaceable insert bearings. The flywheel is new, as is the method of attach ing; the balance factor has'been increased to 85-percent (of the reciprocating mass). This, with changes in the frame we shall cover later, makes the new engine the smoothest of all the big vertical twins.

Modifications have been made in the engine's upper end, too. The barrels are of long-wearing alloy iron, and carry a revised cylinder head stud pattern, with an extra stud tucked in between the bores to help the 8 that were there before. An extra fine touch is seen in the groove machined around the top of each bore on the upper surface of the barrels. The gasket bulges down into this groove when the head is torqued down and it grips the gasket so as to prevent it from blowing outward.

Triumph valve gear has always been unexcelled and it is continued unchanged, but there is a new cylinder head, which has a greater cooling-fin area. Also, the valve-rocker boxes have had finning added; partly in the interest of appearance, but also to give better cooling and rigidity. Material has been added at strategic points in the head casting that, in combination with the extra stud between bores, gives extra rigidity there, too, and holds valve seat distortion to a minimum under conditions of high temperatures and high gas loadings. In anticipation of the sustained high speeds at which these engines are to run, the cam followers have been given brazed-on face blocks of some wear-resistant material - possibly steelite or a near equivalent.

The camshaft drive gears have been widened, for more quiet running and added reliability, and an oilslinger has been incorporated next to the oil breather to eliminate oil loss at that point. A tachometer drive is provided on the left end of the exhaust camshaft and all Bonneville models carry "N" camshafts on the exhaust side; "Q" camshafts are fitted on the intake side. This gives a fairly sporting intake timing combined with a relatively mild exhaust timing, with the result that the engine has a lot of power over a wide speed range - and will idle down nicely, too. Of course, both Bonneville camshafts are a bit more sporty than those found in other engines in the "B" range.

A new, and very worthwhile, change for 1963 is the revised ignition system. There is no distributor, as such; a point plate is housed in the timing case cover, and the breaker cam is driven by the exhaust camshaft. Two points are used, and each of these controls what is, in essence, two entirely separate ignition systems: there are pairs of coils and condensers - one for each spark plug. With such a direct drive, the ignition timing is very precisely controlled, and the system has the added advan tage of being compact and light.

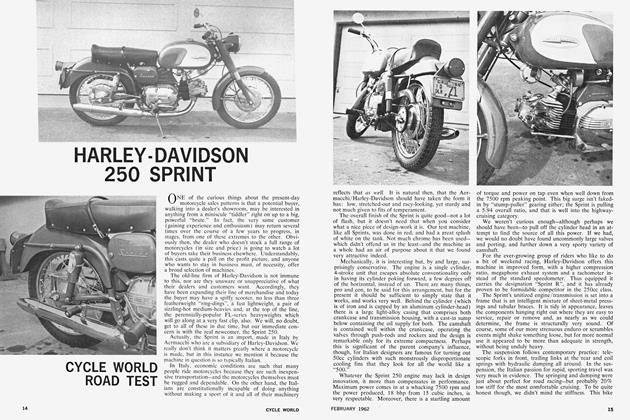

Actually, the Bonneville is available in two stages of tune: the first is the Bonneville "Speed Master," which has 8.5:1 (compression ratio) pistons and dual 1 1/16inch Amal Monobloc carburetors. However, here in the west, Johnson Motors is offering a model called the Bonneville T-l20 TT Special, which the Triumph Factory has kindly consented to produce for them, to their order. This machine, an example of which was loaned to us for this test, is delivered without lighting equipment and has 12:1 (egad!) pistons and 1 3/16-inch carburetors. Where the standard model has 50 bhp at 6500, the TT Special is said to have 52 bhp. Actually, we think the gap between the pair is greater than that; or, perhaps, the peaks given are the same but the TT Special has a lot more power over a wide range of engine speeds on both sides of the peak.

As though to confound our technical editor, who was holding-forth only last month on the great virtues of double down-tube frames, Triumph has abandoned that arrangement in favor of one having a single, large-diam eter down-tube, which hooks into a two-tube cradle under the engine. Although this might seem a retrograde step, even the technical editor will admit that the results justify the change. No alteration has been made in steering angle, or trail, or wheelbase, but the new Bonneville feels more stable, and solid, and the frame tends to subdue engine vibration to an amazing degree. While it is not widely known or appreciated, at least half of the battle against vibration in a motorcycle is fought in the engine mounting and frame. When the engine, its mountings and the frame are right, the rider will not feel much vibration; when they are wrong, he will get a real vibro-massage. In the case of the Bonneville, we are of the opinion that last year's small-diameter down tubes, even though structurally correct, would "twang," just like a pair of fiddle strings, and the rider was painfully aware of this at times (those times being when the frequency of engine vibration matched the natural frequency of the frame tubes). The big single-tube now used is probably little, if any, stronger, but it will not buzz, as the two lighter tubes did.

Vibration damping has been provided in the drive system, too. A duplex chain, with a blade-type tensioner, takes the drive to the clutch - which has a hub that carries a 3-vane shock damper. There is no snatch or pounding in this system. The clutch, incidentally, is new, with the plates driven by a cast-iron housing. The friction material is bonded to the clutch plate and the clutch grips fantastically well, while providing what is surely the smoothest engagement to be found on any big-inch bike. Part of this is due to a redesigned clutch throwout, which now has a wedge-ball device to force the clutch-rod through and push the plates out of engagement. The device in question provides a high mechanical advantage, for light lever pressure, with a minimum of friction.

Those models in the "B" range sold primarily for competition have special electrical systems. Current for the ignition is supplied by a rotating-magnet AC generator, mounted at the drive-end of the crankshaft. This unit will feed enough current even at kick-over rotating speeds to fire the engine, and no battery is required. And, of course, once the engine is running there is more than enough "juice" to make the sparks for high-speed run ning. Certainly, one could not ask for better results than we got from this system during our test. The engine would start easily when cold - even though fitted with Lodge R49 racing spark plugs. And, obviously, that 12: 1 com pression ratio, with its attendant high cylinder pressures, does not make the ignition's task any easier, but the sys tem performed flawlessly nonetheless.

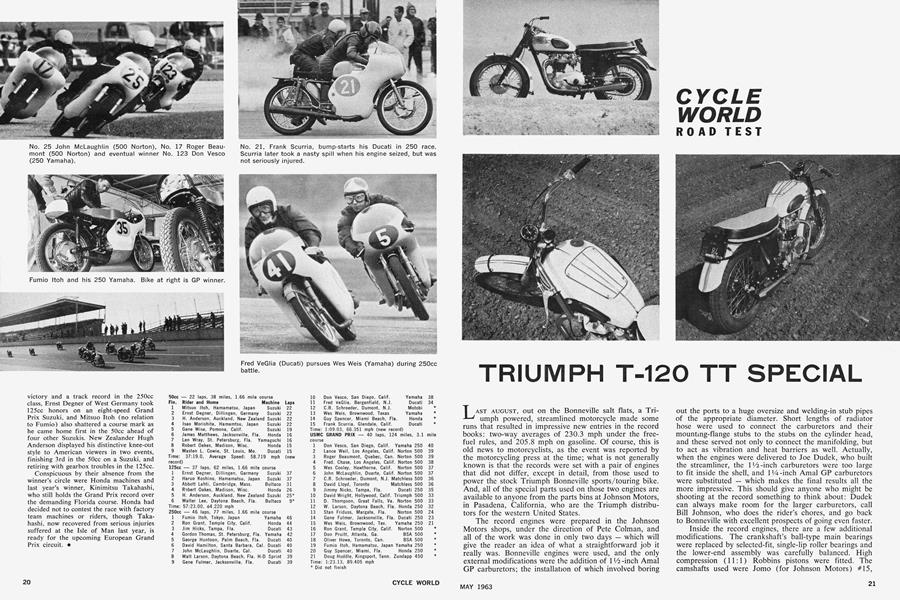

We took the Bonneville TT Special to Harry Schooler's Ascot Park to photograph it in its natural habitat. From the pictures it can be seen that the track was in the arduous, expensive and time-consuming stages of prep aration for the Jimmy Phillips Memorial 100-lap TT which followed two days later, and was won by Skip Van Leeuwen riding a similar machine on its first outing.

Performance-testing of the Bonneville TT Special was done at two different sites: the Long Beach Lions Club drag strip; and for handling evaluation and high-speed testing, Riverside Raceway. The machine was in virtually "from the crate" condition, except for the substitution of downswept exhaust pipes with reverse-cone megaphone. The gearing was, for the high-speed portion of the test, the standard 4.84:1. Later, for an all-out attempt at the drag strip, we installed a 54-tooth overlay sprocket on the rear wheel, changing the gearing to 5.68:1. Pump gasoline was used and no oil was lost or added during the entire duration of testing.

While at Riverside Raceway we discovered that the TT Special was not very fussy about its mixture. Our first run, on 330 main-jets, was at exactly 100 mph. Going up through the jets in gradual stages nudged the spe,ed upward until we got up to 380 jets, and we finally settled on 370 jets as being best for that day. In all, we made what seemed like two-dozen flat-out runs, increasing speed with each try, until we finally got a best run of 123.5 mph - and that was done under the handicap of a rather bothersome side wind. Five consecutive runs were made at speeds over 120 mph. The limit, when it was finally reached, was actually set by the amount that the engine would over-rev without losing too much power, which was about 7900 rpm (the tachometer flickers, even the rider's eye-balls flicker, at that speed and it was impossible to get a really accurate reading). With one more tooth on the countershaft sprocket, we think the stock Bonneville TT Special would push up to about 127 mph, and that is fearfully fast for a machine that can be bought in that condition right from a dealer's floor.

Handling was, as we have said, better than we remembered of the 1962 Bonneville. It was very stable, and yet responsive, and we would someday like to try one with proper road-racing tires and high pegs. While making those high-speed runs in a cross-wind, we discovered that the high-speed response was especially good. We were following a white line marking the center of the straight away, and this gave us a point of reference that allowed us to observe that we were running banked over into the breeze. Interestingly, when the wind was gusty, the bike would tilt sharply into the gusts and seemingly adjust itself to the side pressures without conscious effort from the rider and without straying from the line.

The only complaints we have are that the steering damper had a tendency to vibrate loose, whereupon the handling would become a trifle twitchy, and that the brakes were not quite up to th~ speed potential of the machine. When the brakes were applied hard at the end of a high-speed run (there is a turn at the end of that Riverside Raceway straight), they would shudder notice ably. The bike would pull down quickly enough, but we got the distinct impression that there was little, if any, braking capacity in reserve. Perhaps it is unreasonable to ask for perfect braking on so rapid a mass-produced motorcycle.

After completing our high-speed tests, the TT Special was hauled off to the drag strip and, without changing the gearing, given the grand old American ¼-mile "banzai" try. Pulling the tall gearing, and carrying our 190 lb. (in leathers, helmet and boots) regular test rider, the bike immediately cracked-off a 14-second, 93.4 mph quarter. Then, to see what the TT Special would do if given a chance, we changed to the 5.68:1 gearing and brought our good friend Bennie Sims (a professional Expert-class racer, and husband of Carol Sims, CW's Associate Editor, who weighs about 140 lb. ready to go) into action. Under Bennie's able throttle-twisting and handlebar pointing, the bike soon gave us an even 100 mph at the end of the quarter, with an elapsed time of only 13.34-seconds.

As a final measure, just to assure us that we had been running the Real Thing, and not a super, super-tuned Triumph, the bike's engine was torn down for our inspec tion, and duly certified as stock. We are also happy to certify that despite the unmerciful flogging the bike received, the engine was still in excellent condition.

Actually, the stockness of the TT Special is of limited importance, as the machine will be delivered with any of several engine and drive options, at the customer's request. Even so, we think it is interesting, and there is the fact that many people are buying this bike for ordinary Street riding - and it is mild enough for that sort of running, too. While primarily for racing, it can be outfitted with lights, and it has, as standard, Triumph's big, comfortable tour ing-type saddle. And, there is no disputing that it is, among the machines we have tested, the fastest of them all - regardless of displacement. The performance oriented rider, whether he intends to race or just likes a lot of power on tap for touring, will be hard put to find more sheer flashing speed than is provided by the Bonneville TT Special. •

TRIUMPH BONNEVILLE TT SPECIAL

SPECI FICATIONS

$1,158

PERFORMANCE