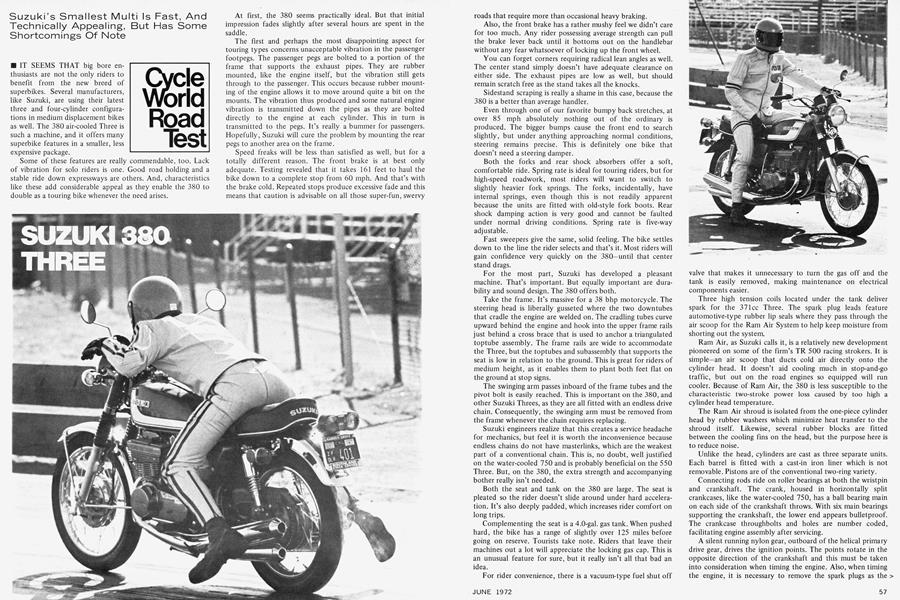

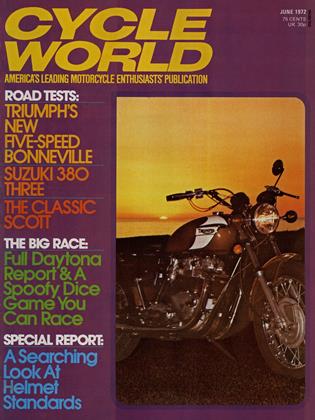

SUZUKI 380 THREE

Cycle World Road Test

Suzuki's Smallest Multi Is Fast, And Technically Appealing, But Has Some Shortcomings Of Note

IT SEEMS THAT big bore enthusiasts are not the only riders to benefit from the new breed of superbikes. Several manufacturers, like Suzuki, are using their latest three and four-cylinder configurations in medium displacement bikes as well. The 380 air-cooled Three is such a machine, and it offers many superbike features in a smaller, less expensive package.

Some of these features are really commendable, too. Lack of vibration for solo riders is one. Good road holding and a stable ride down expressways are others. And, characteristics like these add considerable appeal as they enable the 380 to double as a touring bike whenever the need arises.

At first, the 380 seems practically ideal. But that initial impression fades slightly after several hours are spent in the saddle.

The first and perhaps the most disappointing aspect for touring types concerns unacceptable vibration in the passenger footpegs. The passenger pegs are bolted to a portion of the frame that supports the exhaust pipes. They are rubber mounted, like the engine itself, but the vibration still gets through to the passenger. This occurs because rubber mount ing of the engine allows it to move around quite a bit on the mounts. The vibration thus produced and some natural engine vibration is transmitted down the pipes as they are bolted directly to the engine at each cylinder. This in turn is transmitted to the pegs. It's really a bummer for passengers. Hopefully, Suzuki will cure the problem by mounting the rear pegs to another area on the frame.

Speed freaks will be less than satisfied as well, but for a totally different reason. The front brake is at best only adequate. Testing revealed that it takes 161 feet to haul the bike down to a complete stop from 60 mph. And that's with the brake cold. Repeated stops produce excessive fade and this means that caution is advisable on all those super-fun, swervy roads that require more than occasional heavy braking.

Also, the front brake has a rather mushy feel we didn’t care for too much. Any rider possessing average strength can pull the brake lever back until it bottoms out on the handlebar without any fear whatsoever of locking up the front wheel.

You can forget corners requiring radical lean angles as well. The center stand simply doesn’t have adequate clearance on either side. The exhaust pipes are low as well, but should remain scratch free as the stand takes all the knocks.

Sidestand scraping is really a shame in this case, because the 380 is a better than average handler.

Even through one of our favorite bumpy back stretches, at over 85 mph absolutely nothing out of the ordinary is produced. The bigger bumps cause the front end to search slightly, but under anything approaching normal conditions, steering remains precise. This is definitely one bike that doesn’t need a steering damper.

Both the forks and rear shock absorbers offer a soft, comfortable ride. Spring rate is ideal for touring riders, but for high-speed roadwork, most riders will want to switch to slightly heavier fork springs. The forks, incidentally, have internal springs, even though this is not readily apparent because the units are fitted with old-style fork boots. Rear shock damping action is very good and cannot be faulted under normal driving conditions. Spring rate is five-way adjustable.

Fast sweepers give the same, solid feeling. The bike settles down to the line the rider selects and that’s it. Most riders will gain confidence very quickly on the 380—until that center stand drags.

For the most part, Suzuki has developed a pleasant machine. That’s important. But equally important are durability and sound design. The 380 offers both.

Take the frame. It’s massive for a 38 bhp motorcycle. The steering head is liberally gusseted where the two downtubes that cradle the engine are welded on. The cradling tubes curve upward behind the engine and hook into the upper frame rails just behind a cross brace that is used to anchor a triangulated toptube assembly. The frame rails are wide to accommodate the Three, but the toptubes and subassembly that supports the seat is low in relation to the ground. This is great for riders of medium height, as it enables them to plant both feet flat on the ground at stop signs.

The swinging arm passes inboard of the frame tubes and the pivot bolt is easily reached. This is important on the 380, and other Suzuki Threes, as they are all fitted with an endless drive chain. Consequently, the swinging arm must be removed from the frame whenever the chain requires replacing.

Suzuki engineers realize that this creates a service headache for mechanics, but feel it is worth the inconvenience because endless chains do not have masterlinks, which are the weakest part of a conventional chain. This is, no doubt, well justified on the water-cooled 750 and is probably beneficial on the 550 Three. But, on the 380, the extra strength and accompanying bother really isn’t needed.

Both the seat and tank on the 380 are large. The seat is pleated so the rider doesn’t slide around under hard acceleration. It’s also deeply padded, which increases rider comfort on long trips.

Complementing the seat is a 4.0-gal. gas tank. When pushed hard, the bike has a range of slightly over 125 miles before going on reserve. Tourists take note. Riders that leave their machines out a lot will appreciate the locking gas cap. This is an unusual feature for sure, but it really isn’t all that bad an idea.

For rider convenience, there is a vacuum-type fuel shut off valve that makes it unnecessary to turn the gas off and the tank is easily removed, making maintenance on electrical components easier.

Three high tension coils located under the tank deliver spark for the 371cc Three. The spark plug leads feature automotive-type rubber lip seals where they pass through the air scoop for the Ram Air System to help keep moisture from shorting out the system.

Ram Air, as Suzuki calls it, is a relatively new development pioneered on some of the firm’s TR 500 racing strokers. It is simple—an air scoop that ducts cold air directly onto the cylinder head. It doesn’t aid cooling much in stop-and-go traffic, but out on the road engines so equipped will run cooler. Because of Ram Air, the 380 is less susceptible to the characteristic two-stroke power loss caused by too high a cylinder head temperature.

The Ram Air shroud is isolated from the one-piece cylinder head by rubber washers which minimize heat transfer to the shroud itself. Likewise, several rubber blocks are fitted between the cooling fins on the head, but the purpose here is to reduce noise.

Unlike the head, cylinders are cast as three separate units. Each barrel is fitted with a cast-in iron liner which is not removable. Pistons are of the conventional two-ring variety.

Connecting rods ride on roller bearings at both the wristpin and crankshaft. The crank, housed in horizontally split crankcases, like the water-cooled 750, has a ball bearing main on each side of the crankshaft throws. With six main bearings supporting the crankshaft, the lower end appears bulletproof. The crankcase throughbolts and holes are number coded, facilitating engine assembly after servicing.

A silent running nylon gear, outboard of the helical primary drive gear, drives the ignition points. The points rotate in the opposite direction of the crankshaft and this must be taken into consideration when timing the engine. Also, when timing the engine, it is necessary to remove the spark plugs as the nylon gear may be damaged if the engine is turned over by hand against compression.

As mentioned above, helical gear drive transmits power to the six-speed transmission. Shifting is precise, and going through all six speeds is fun, but the relatively broad powerband makes the sixth cog unnecessary. As is, the ratios are well spaced, but the transmission must be shifted more often than is pleasant in traffic because of the closeness on the lower cogs.

The clutch could stand to be a little heftier. It doesn’t slip or require any adjusting to speak of under normal driving conditions, but several runs at the drags (without clutch slipping) proved a little too much for the unit. The clutch never began to slip, but the cable free-play had to be adjusted every three or four runs, and then backed off again as the unit cooled.

Clutch feel, though, is light and engagement is progressive. This progressive engagement and rubber cushioning blocks in the rear hub aid smooth starts, even on hills.

An autolube system precludes mixing gas and oil as usual, but there have been some refinements which provide less exhaust smoke. When a two-stroke is operated at low speed, unburned oil collects in the bottom of the crankcase. When a conventional two-stroke is accelerated hard, this oil that has been collecting in the cases is forced, all at once, into the combustion chamber. Incomplete combustion and excessive smoke are the results.

The 380, though, has a one way valve in the bottom of each crankcase which is connected by a rubber tube to an adjacent cylinder’s transfer port. Instead of collecting, oil is constantly burned, thus reducing smoke even though oil consumption has not been reduced.

SUZUKI

380 THREE

Three 24mm Mikuni carburetors are used in conjunction with this oiling system. Jetting on our test machine was spot on. Throttle response was excellent and starting was a one-kick affair. The carbs should stay in synchronization fairly well, too, as they are rubber mounted to isolate them from vibration. In addition, each rubber connector is notched, making it easy to return the carbs to their proper vertical position following adjustment. This is especially beneficial on the hard-to-reach center unit.

The plastic aircleaner, box and its rubber hose connecting arrangement is located under the seat, just in front of the oil tank. The unit is commendable because it incorporates a

downward-pointing intake snout which keeps intake noise to a bare minimum.

Exhaust noise, on the other hand, is a little louder than we expected when the bike is being pushed, but below 6000 rpm the sound level is well below average. Four separate exhaust pipes are used, as on the 750, and they give the Three a symmetrical appearance. The bottom two pipes exhaust the center cylinder, and together provide the same internal pipe dimensions as one of the larger units. Unlike the 750, though, balance pipes are not used.

Taken as a whole, the power unit is fairly bulky for a displacement of 371cc, even though its weight is a reasonable 124 lb. This is excusable in a touring oriented machine, perhaps.

So what do we have? A technically appealing medium multi. Potentially, a fun machine. But it needs some debugging. Q