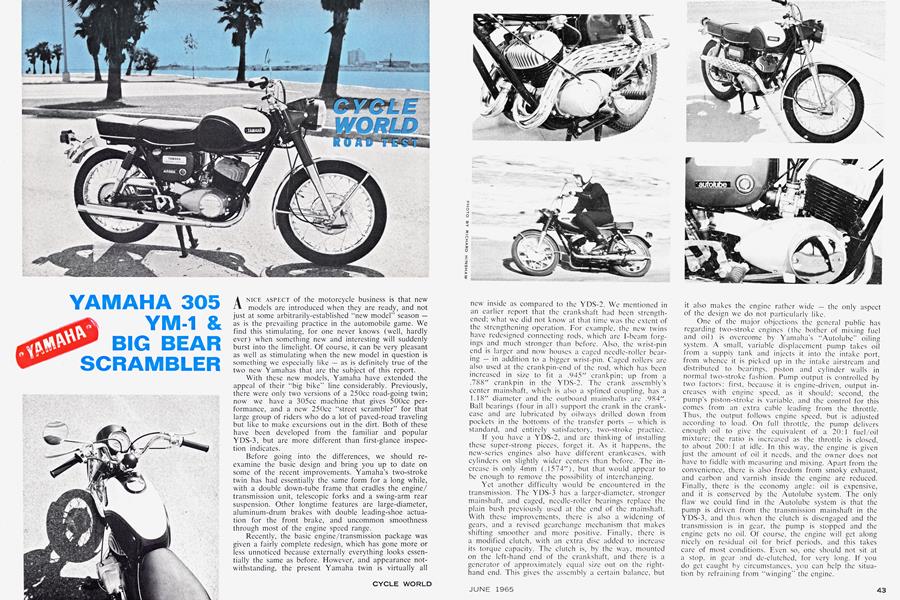

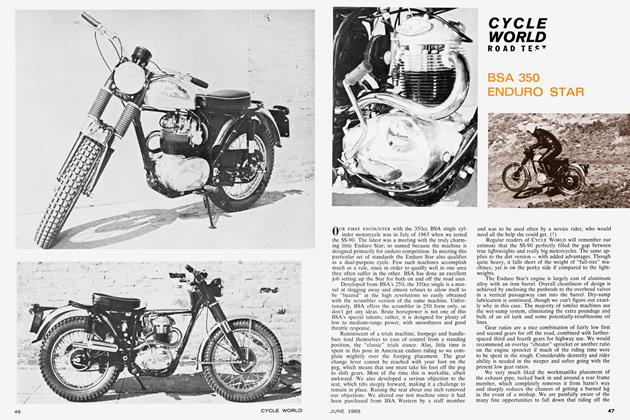

YAMAHA 305 YM-1 & BIG BEAR SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A NICE ASPECT of the motorcycle business is that new models are introduced when they are ready, and not just at some arbitrarily-established "new model" season — as is the prevailing practice in the automobile game. We find this stimulating, for one never knows (well, hardly ever) when something new and interesting will suddenly burst into the limelight. Of course, it can be very pleasant as well as stimulating when the new model in question is something we especially like - as is definitely true of the two new Yamahas that are the subject of this report.

With these new models, Yamaha have extended the appeal of their "big bike" line considerably. Previously, there were only two versions of a 250cc road-going twin; now we have a 305cc machine that gives 500cc performance, and a new 250cc "street scrambler" for that large group of riders who do a lot of paved-road traveling but like to make excursions out in the dirt. Both of these have been developed from the familiar and popular YDS-3, but are more different than first-glance inspection indicates.

Before going into the differences, we should reexamine the basic design and bring you up to date on some of the recent improvements. Yamaha's two-stroke twin has had essentially the same form for a long while, with a double down-tube frame that cradles the engine/ transmission unit, telescopic forks and a swing-arm rear suspension. Other longtime features are large-diameter, aluminum-drum brakes with double leading-shoe actuation for the front brake, and uncommon smoothness through most of the engine speed range.

Recently, the basic engine/transmission package was given a fairly complete redesign, which has gone more or less unnoticed because externally everything looks essentially the same as before. However, and appearance notwithstanding, the present Yamaha twin is virtually all new inside as compared to the YDS-2. We mentioned in an earlier report that the crankshaft had been strengthened; what we did not know at that time was the extent of the strengthening operation. For example, the new twins have redesigned connecting rods, which are I-beam forgings and much stronger than before. Also, the wrist-pin end is larger and now houses a caged needle-roller bearing — in addition to a bigger wrist-pin. Caged rollers are also used at the crankpin-end of the rod, which has been increased in size to fit a .945" crankpin; up from a .788" crankpin in the YDS-2. The crank assembly's center mainshaft, which is also a splined coupling, has a 1.18" diameter and the outboard mainshafts are .984". Ball bearings (four in all) support the crank in the crankcase and are lubricated by oilways drilled down from pockets in the bottoms of the transfer ports — which is standard, and entirely satisfactory, two-stroke practice.

If you have a YDS-2, and are thinking of installing these super-strong pieces, forget it. As it happens, the new-series engines also have different crankcases, with cylinders on slightly wider centers than before. The increase is only 4mm (.1574"), but that would appear to be enough to remove the possibility of interchanging.

Yet another difficulty would be encountered in the transmission. The YDS-3 has a larger-diameter, stronger mainshaft, and caged, needle-roller bearings replace the plain bush previously used at the end of the mainshaft. With these improvements, there is also a widening of gears, and a revised gearchange mechanism that makes shifting smoother and more positive. Finally, there is a modified clutch, with an extra disc added to increase its torque capacity. The clutch is, by the way, mounted on the left-hand end of the crankshaft, and there is a generator of approximately equal size out on the righthand end. This gives the assembly a certain balance, but

it also makes the engine rather wide — the only aspect of the design we do not particularly like.

One of the major objections the general public has regarding two-stroke engines (the bother of mixing fuel and oil) is overcome by Yamaha's "Autolube" oiling system. A small, variable displacement pump takes oil from a supply tank and injects it into the intake port, from whence it is picked up in the intake airstream and distributed to bearings, piston and cylinder walls in normal two-stroke fashion. Pump output is controlled by two factors: first, because it is engine-driven, output increases with engine speed, as it should; second, the pump s piston-stroke is variable, and the control for this comes from an extra cable leading from the throttle. Thus, the output follows engine speed, but is adjusted according to load. On full throttle, the pump delivers enough oil to give the equivalent of a 20:1 fuel/oil mixture; the ratio is increased as the throttle is closed, to about 200: 1 at idle. In this way, the engine is given just the amount of oil it needs, and the owner does not have to fiddle with measuring and mixing. Apart from the convenience, there is also freedom from smoky exhaust, and carbon and varnish inside the engine are reduced. Finally, there is the economy angle: oil is expensive, and it is conserved by the Autolube system. The only flaw we could find in the Autolube system is that the pump is driven from the transmission mainshaft in the YDS-3, and thus when the clutch is disengaged and the transmission is in gear, the pump is stopped and the engine gets no oil. Of course, the engine will get along nicely on residual oil for brief periods, and this takes care of most conditions. Even so, one should not sit at a stop, in gear and de-clutched, for very long. If you do get caught by circumstances, you can help the situation by refraining from "winging" the engine.

And now for the new models: first, there is the 305, which carries the official Yamaha designation, YM-1. This machine is much like the YDS-3, but where the YDS-3 has bore and stroke dimensions of 56 x 50mm, and a displacement of 246cc, the YM-l's dimensions are 60 x 54mm — giving it a total piston displacement of 305cc. Apparently, the YM-1 has essentially the same port timing as the YDS-3, for its torque peak is at the same 6000 rpm. However, the torque value has been increased by almost 20-percent, which could doubtless have been more, considering the 24-percent increase in displacement, except that the compression ratio has been reduced from 7.5:1 to 7.1:1. The low compression ratio has the advantage of lowering heat input to the pistons, an important consideration in the thermally-overloaded two-stroke. And, too, there is the fact that the Yamaha will accept regular-grade fuel without complaint. In this country, where relatively high wages and low gasoline prices prevail, the ability to run on regular fuel is of less consequence than abroad, but it is a factor. The Yamaha 305 has, it seems, the appetite of a 500 — which can be excused on the grounds that it also has a 500's performance.

With the increased displacement there has been an increase in torque, as we have mentioned, and you also get a boost in horsepower. The 305cc engine pumps out 26 bhp at 7000 rpm (compared to the YDS-3's 24 at 7500), which is not a big increase, on top, but it is spread out very nicely, and the 305 pulls very strongly over a wide speed range.

Transmission ratios in the YM-1 have been revised from those in the YDS-3. Curiously, there is no big difference: first and second gears slightly "taller", and the gap between 4th and 5th has been closed. In any case, the ratios match engine output characteristics very well, and there can be little doubt but that the Yamaha's 5-speed transmission contributes very materially to its exceptional performance.

Apart from the changes in bore/stroke dimensions and gearing, the YM-1 is not unlike the YDS-3. Having the same carburetor size as the smaller-displacement YDS-3, it is more tractable at low speeds, and the added "inches" give it better performance. However, the biggest differences we noted were that the YM-1 will pull away from a stop with much less blipping of engine and slipping of clutch; and that it is actually smoother. The YDS-3, when cruising along in 5th gear, is turbine-smooth up to 60 mph; then it begins to produce the usual 2cylinder "buzz". For reasons we cannot entirely fathom (although the slightly taller overall ratio must have its effect) the YM-1 retains its turbine-like character up past 70 mph, which means that in the vast majority of these United States, you can cruise at, or somewhat over, the legal maximum and still have complete smoothness. Now we would like to make it perfectly clear that we are not talking about "smooth" in the usual motorcycle 2-cylinder context; we mean smooth like a big, slow-turning, rubber-mounted V-8. The YM-1 Yamaha simply doesn't vibrate at all, to any perceptible extent, until it climbs up past 7000 rpm — and even beyond that point it is not overly obtrusive. And, because one seldom needs to exceed 6000 rpm, the Yamaha is, in practical terms, completely vibrationless. Smoother than anything else we have tested — and that includes the theoretically better-balanced opposed twins like the BMW and Marusho.

As a comparison-piece to their strictly road-going 250 twins, Yamaha have also introduced the YDS-3C "Big Bear" scrambler. Yamaha have had their Ascot scrambler available for some time, but it is a racing machine, pure and simple, while the Big Bear is a sort of street-scrambler. The Big Bear carries full road equipment, and is basically a YDS-3, but has high pipes and a skid-plate under the engine to make it suitable for off-the-road riding. The standard-equipment tires aren't much good in mud, or sand, but they get a better grip in the dirt than ordinary street tires, and they are entirely in keeping with the dualpurpose nature of the machine. The more enthusiastic brush-bashers will probably change the tires and remove all of the road-going lighting equipment — which is made quickly detachable in anticipation of precisely that sort of person.

The Big Bear has the YDS-3's 250 engine, but with a bit more compression (7.8:1) and it is set up for broad-range torque rather than horsepower. Even so, you can remove the baffle-tubes from the "mufflers" and boost the power from the standard 21 up to 26 bhp. When this is done, the power peak remains the same, at 7500 rpm, but the torque peak climbs 500 rpm to 6500 rpm.

Although the first three of the transmission ratios for the Big Bear are the same as those in the YDS-3, 4th and 5th have been "lowered" to give a close-ratio setup. The overall drive ratio is, at 7.697:1, substantially different from the YDS-3. Not as good for highway cruising, but just what is needed out in the dirt.

You also get alterations in the spring-rates and damping with the Big Bear: these are stiffer, for reasons that should be obvious. Fortunately, the makers did not go overboard with this, and the bike is still a good-riding street machine in addition to being agreeable to a bit of back-country riding. The bike carries the designation "scrambler", but it is in fact a dual-purpose sporting machine and we would suggest that you not try to change that. We consider it too heavy for serious scrambling, so it will not respond well to attempts in that direction. On the other hand, it is something you can ride to and from the office, and still go out and bash about in the hills when the mood for that sort of thing is upon you. In this connection, we would also like to suggest that you do not pull the muffler baffles. The added power will probably not be worth the attention you will get from lawenforcement officers. Even the standard system, with baffles in place, is a trifle too noisy for most peoples' tastes, and it is our one criticism of this machine. We could obviously criticize on the grounds that it is not really a very good scrambler, but that would not be fair. Good scramblers cannot be ridden on the street at all, and if one accepts the dual-purpose nature of the Big Bear, then it scores rather well.

Both the Big Bear and the 305 have all the usual Yamaha good things, such as a really good level of quality and finish. Both come with a combined speedo and tachometer, excellent brakes and handling, and considerable riding comfort. Easy starting is also a Yamaha characteristic. The carburetors have a small mixtureenrichment device for cold starting that really does the trick and usually a couple of kicks will bring the engine to life. There is a marked reluctance to pull the motorcycle until a couple of minutes have been spent in warmup, but this is better than having an engine that warms up instantly-after you have become exhausted in starting it. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue