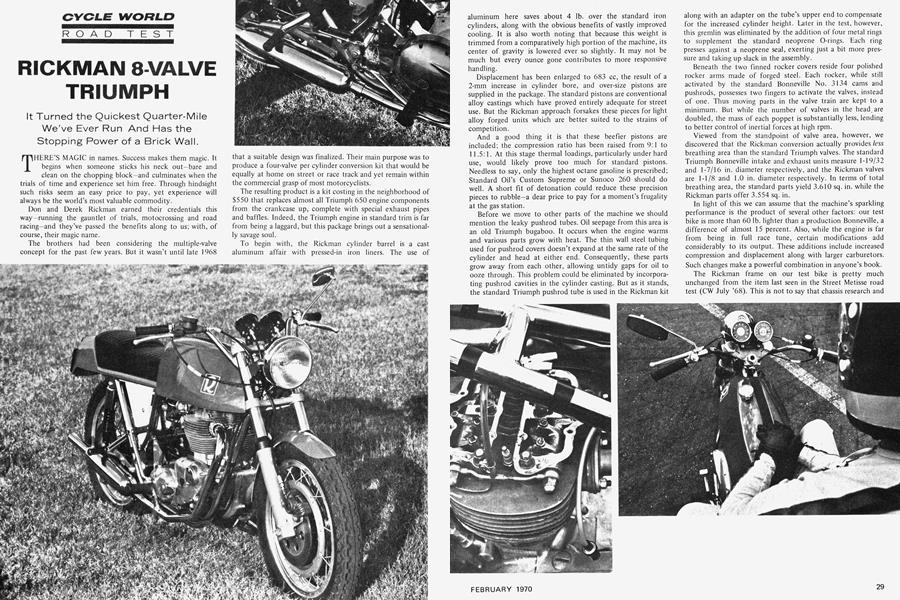

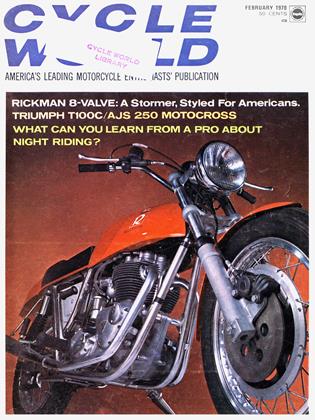

RICKMAN 8-VALVE TRIUMPH

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

It Turned the Quickest Quarter-Mile We’ve Ever Run And Has the Stopping Power of a Brick Wall.

THERE'S MAGIC in names. Success makes them magic. It begins when someone sticks his neck out—bare and clean on the chopping block—and culminates when the trials of time and experience set him free. Through hindsight such risks seem an easy price to pay, yet experience will always be the world's most valuable commodity.

Don and Derek Rickman earned their credentials this way-running the gauntlet of trials, motocrossing and road racing—and they’ve passed the benefits along to us; with, of course, their magic name.

The brothers had been considering the multiple-valve concept for the past few years. But it wasn’t until late 1968 that a suitable design was finalized. Their main purpose was to produce a four-valve per cylinder conversion kit that would be equally at home on street or race track and yet remain within the commercial grasp of most motorcyclists.

The resulting product is a kit costing in the neighborhood of $550 that replaces almost all Triumph 650 engine components from the crankcase up, complete with special exhaust pipes and baffles. Indeed, the Triumph engine in standard trim is far from being a laggard, but this package brings out a sensationally savage soul.

To begin with, the Rickman cylinder barrel is a cast aluminum affair with pressed-in iron liners. The use of aluminum here saves about 4 lb. over the standard iron cylinders, along with the obvious benefits of vastly improved cooling. It is also worth noting that because this weight is trimmed from a comparatively high portion of the machine, its center of gravity is lowered ever so slightly. It may not be much but every ounce gone contributes to more responsive handling.

Displacement has been enlarged to 683 cc, the result of a 2-mm increase in cylinder bore, and over-size pistons are supplied in the package. The standard pistons are conventional alloy castings which have proved entirely adequate for street use. But the Rickman approach forsakes these pieces for light alloy forged units which are better suited to the strains of competition.

And a good thing it is that these beefier pistons are included; the compression ratio has been raised from 9:1 to 11.5:1. At this stage thermal loadings, particularly under hard use, would likely prove too much for standard pistons. Needless to say, only the highest octane gasoline is prescribed; Standard Oil’s Custom Supreme or Sunoco 260 should do well. A short fit of detonation could reduce these precision pieces to rubble-a dear price to pay for a moment’s frugality at the gas station.

Before we move to other parts of the machine we should mention the leaky pushrod tubes. Oil seepage from this area is an old Triumph bugaboo. It occurs when the engine warms and various parts grow with heat. The thin wall steel tubing used for pushrod covers doesn’t expand at the same rate of the cylinder and head at either end. Consequently, these parts grow away from each other, allowing untidy gaps for oil to ooze through. This problem could be eliminated by incorporating pushrod cavities in the cylinder casting. But as it stands, the standard Triumph pushrod tube is used in the Rickman kit along with an adapter on the tube’s upper end to compensate for the increased cylinder height. Later in the test, however, this gremlin was eliminated by the addition of four metal rings to supplement the standard neoprene O-rings. Each ring presses against a neoprene seal, exerting just a bit more pressure and taking up slack in the assembly.

Beneath the two finned rocker covers reside four polished rocker arms made of forged steel. Each rocker, while still activated by the standard Bonneville No. 3134 cams and pushrods, possesses two fingers to activate the valves, instead of one. Thus moving parts in the valve train are kept to a minimum. But while the number of valves in the head, are doubled, the mass of each poppet is substantially less, lending to better control of inertial forces at high rpm.

Viewed from the standpoint of valve area, however, we discovered that the Rickman conversion actually provides less breathing area than the standard Triumph valves. The standard Triumph Bonneville intake and exhaust units measure 1-19/32 and 1-7/16 in. diameter respectively, and the Rickman valves are 1-1/8 and 1.0 in. diameter respectively. In terms of total breathing area, the standard parts yield 3.610 sq. in. while the Rickman parts offer 3.554 sq. in.

In light of this we can assume that the machine’s sparkling performance is the product of several other factors: our test bike is more than 60 lb. lighter than a production Bonneville, a difference of almost 15 percent. Also, while the engine is far from being in full race tune, certain modifications add considerably to its output. These additions include increased compression and displacement along with larger carburetors. Such changes make a powerful combination in anyone’s book.

The Rickman frame on our test bike is pretty much unchanged from the item last seen in the Street Metisse road test (CW July ’68). This is not to say that chassis research and development has ground to a halt in Don and Derek’s den, but that an excellent configuration has been attained, and for the time being, effort is now spent developing other components. Suffice it to say, the handsome nickle plated, bronze welded, Reynolds steel frame exemplifies the best precision of master craftsmen, it is rigid, and handling is extremely stable, over anything from pockmarks to railroad tracks.

In keeping with the machine’s tenor, a giant 10-in. diameter Lockheed disc brake is fitted to the Rickman front fork. This unit is extremely smooth and responsive, demanding neither uncomfortably high pressure at the lever nor the sensitive touch of a GP veteran to achieve optimum braking efficiency. Nor did repeated high speed applications result in sponginess or chatter as pucks and disc absorb the energy of the hurtling machine.

A disc binder is also implemented at the rear wheel. But because it is operated by one’s foot, and because said foot is not so sensitive as the hand, more care is warranted when using it. To avoid locking the rear wheel light application is advised.

It would be a great injustice to omit praise of the bike’s superlative brakes. During the test they achieved the shortest 60 mph-to-0 stopping distance ever recorded by this magazine. Now, if this machine were a super-pizazz road racer weighing a hundred pounds less or so, our astonishment might be mitigated. But the Rickman Triumph, replete with fiberglass accoutrements, is a street bike tipping the scales at 359 lb.!

Adding to its credentials as a State-Of-The-Art motorcycle are the quarter-mile acceleration figures. The Rickman Triumph thundered through the clocks with a 13.08-sec. elapsed time and 102.50 mph. Ensuring that this was no fluke recording, the bike again zapped down the strip. This time it registered 104.16 mph in 13.11 sec.! By a comfortable margin this is the quickest and fastest accelerating motorcycle tested by CYCLE WORLD.

Which brings us to another point. Contemporary thought has always placed the value of such multi-valve arrangements in the upper rpm ranges where valve control is so critical. But as the test machine was redlined at 7000 rpm and utilized box stock cams, that dictum has been effectively blown into the weeds. Obviously, the engine’s breathing is vastly improved along the entire rpm scale rather than merely after the point of conventional value failure.

Starting the Rickman Triumph is a good deal easier than anticipated. The specter of that 11.5:1 compression ratio and a pair of 32-mm Amal Concentric carburetors (stock units are 30 mm) does little to encourage first kick starts. But the machine lights with surprisingly little effort. Seldom is more than two dabs at the starter lever necessary to bring the bike to life.

Incidentally, these larger carburetors are included in the Rickman eight-valve kit as are all the vital gaskets, nuts, bolts and studs. Offered optionally are two 34-mm carburetors and manifold along with a special exhaust system, boosting output an additional 5 bhp to 70 bhp at 7000 rpm. For this latter stage of tune the Rickmans recommend that the crankshaft be endowed with more stamina through heat treating and that a special gear type oil pump be added. Otherwise, in the interest of long term reliability, the brothers advise a 7000-rpm rev limit. In the upper end, however, Derek Rickman indicated that the valve gear is capable of 9000 rpm with safety.

Inveterate dreamers that we are, images of a robust Rickman lower end conversion fill our heads like sugar plums. Just imagine, an eight-valve large displacement Twin with 9000 rpm reliability—a short step away from a street-GP bike!

RICKMAN 8-VALVE TRIUMPH

$550

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1970 -

Features

FeaturesNight Rider

February 1970 By Stuart Munro -

Features

FeaturesHow To Teach Your Girl To Ride

February 1970 By David C. Hon -

Special Color Feature

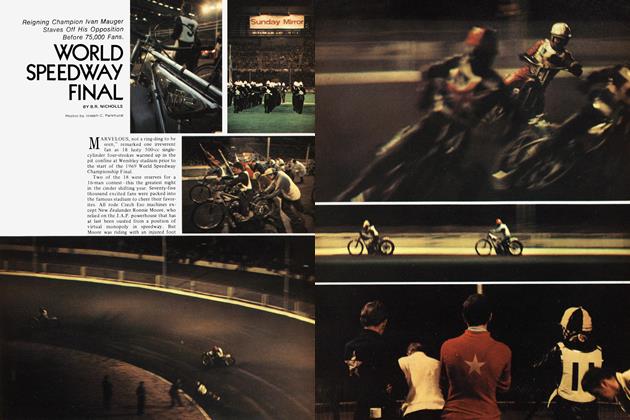

Special Color FeatureWorld Speedway Final

February 1970 By B.R. Nicholls