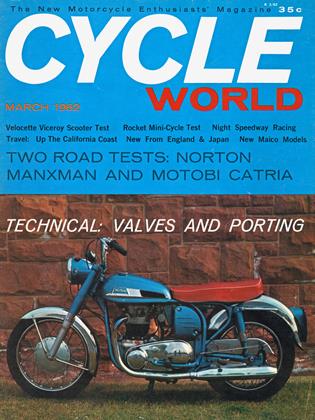

NORTON MANXMAN

Cycle World Road Test

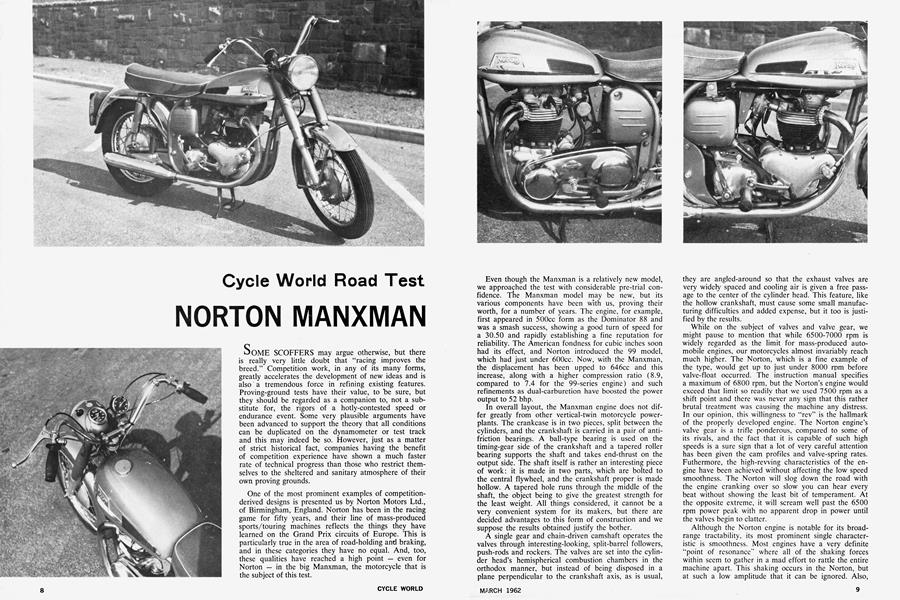

SOME SCOFFERS may argue otherwise, but there is really very little doubt that “racing improves the breed.” Competition work, in any of its many forms, greatly accelerates the development of new ideas and is also a tre mendous force in refining existing features. Proving-ground tests have their value, to be sure, but they should be regarded as a companion to, not a substitute for, the rigors of a hotly-contested speed or endurance event. Some very plausible arguments have been advanced to support the theory that all conditions can be duplicated on the dynamometer or test track and this may indeed be so. However, just as a matter of strict historical fact, companies having the benefit of competition experience have shown a much faster rate of technical progress than those who restrict themselves to the sheltered and sanitary atmosphere of their own proving grounds.

One of the most prominent examples of competitionderived designs is presented us by Norton Motors Ltd., of Birmingham, England. Norton has been in the racing game for fifty years, and their line of mass-produced sports/touring machines reflects the things they have learned on the Grand Prix circuits of Europe. This is particularly true in the area of road-holding and braking, and in these categories they have no equal. And, too, these qualities have reached a high point — even for Norton — in the big Manxman, the motorcycle that is the subject of this test.

Even though the Manxman is a relatively new model, we approached the test with considerable pre-trial confidence. The Manxman model may be new, but its various components have been with us, proving their worth, for a number of years. The engine, for example, first appeared in 500cc form as the Dominator 88 and was a smash success, showing a good turn of speed for a 30.50 and rapidly establishing a fine reputation for reliability. The American fondness for cubic inches soon had its effect, and Norton introduced the 99 model, which had just under 600cc. Now, with the Manxman, the displacement has been upped to 646cc and this increase, along with a higher compression ratio (8.9, compared to 7.4 for the 99-series engine) and such refinements as dual-carburetion have boosted the power output to 52 bhp.

In overall layout, the Manxman engine does not differ greatly from other vertical-twin motorcycle powerplants. The crankcase is in two pieces, split between the cylinders, and the crankshaft is carried in a pair of antifriction bearings. A ball-type bearing is used on the timing-gear side of the crankshaft and a tapered roller bearing supports the shaft and takes end-thrust on the output side. The shaft itself is rather an interesting piece of work: it is made in two parts, which are bolted to the central flywheel, and the crankshaft proper is made hollow. A tapered hole runs through the middle of the shaft, the object being to give the greatest strength for the least weight. All things considered, it cannot be a very convenient system for its makers, but there are decided advantages to this form of construction and we suppose the results obtained justify the bother.

A single gear and chain-driven camshaft operates the valves through interesting-looking, split-barrel followers, push-rods and rockers. The valves are set into the cylinder head’s hemispherical combustion chambers in the orthodox manner, but instead of being disposed in a plane perpendicular to the crankshaft axis, as is usual, they are angled-around so that the exhaust valves are very widely spaced and cooling air is given a free passage to the center of the cylinder head. This feature, like the hollow crankshaft, must cause some small manufacturing difficulties and added expense, but it too is justified by the results.

While on the subject of valves and valve gear, we might pause to mention that while 6500-7000 rpm is widely regarded as the limit for mass-produced automobile engines, our motorcycles almost invariably reach much higher. The Norton, which is a fine example of the type, would get up to just under 8000 rpm before valve-float occurred. The instruction manual specifies a maximum of 6800 rpm, but the Norton’s engine would exceed that limit so readily that we used 7500 rpm as a shift point and there was never any sign that this rather brutal treatment was causing the machine any distress. In our opinion, this willingness to “rev” is the hallmark of the properly developed engine. The Norton engine’s valve gear is a trifle ponderous, compared to some of its rivals, and the fact that it is capable of such high speeds is a sure sign that a lot of very careful attention has been given the cam profiles and valve-spring rates. Futhermore, the high-revving characteristics of the engine have been achieved without affecting the low speed smoothness. The Norton will slog down the road with the engine cranking over so slow you can hear every beat without showing the least bit of temperament. At the opposite extreme, it will scream well past the 6500 rpm power peak with no apparent drop in power until the valves begin to clatter.

Although the Norton engine is notable for its broadrange tractability, its most prominent single characteristic is smoothness. Most engines have a very definite “point of resonance” where all of the shaking forces within seem to gather in a mad effort to rattle the entire machine apart. This shaking occurs in the Norton, but at such a low amplitude that it can be ignored. Also, there are no shaking periods within the speed range normally used and therefore, to all practical purposes, the engine may be considered as absolutely smooth. Our only adverse comment is that the engine does not appear to have quite as much power as the sales brochures would lead one to believe. Of course, our test bike showed signs of having been used very hard and its engine was very definitely not au point. So, the lack of power we noticed may have been characteristic of only this one machine, and not indicative of what one might expect from another example of the Manxman in perfect tune.

Whatever else may be said of the Norton engine, it can be honestly stated that it is set into the finest frame and-suspension package that can be purchased today. The design has been taken directly from the famous `Featherbed" racing model and if ever there was a case of racing's imnrovin~ something. this is it.

.a~c Ut IIIIpI~JviiL~ iiii~iiiiii~, L1U~ i~ ii. The frame is of the tubular type, very straightforward in layout and consisting, primarily, of a pair of loops which intersect and cross over just behind the steering head. Sheet metal brackets reinforce the frame at this critical point and there is additional bracing of the same sort around the attaching points of the rear suspension.

At the front of this assembly are Norton's "Road holder" front forks. These look much the same as any telescopic-type fork, but they give very superior results. The only feature we could find that gave any clue as to the reason for their effectiveness was that there seemed to be more than an average amount of travel, and that the springs were softer and the damping action a bit stiffer than is usual. Approximately the same thing was also true of the rear suspension, which was of the trailing link type (a pattern that has become uni versal) and had adjustable-for-load spring/damper units taking the bounce. It is perhaps significant of the faith the makers have in the Manxman frame and suspension that they have fitted no steering damper.

tnat tney nave ritieu no steering aamper. The seating and control positioning are quite good and the instrumentation was complete. A very business like and accurate chronometric tachometer is mounted right up in plain view and there is a speedometer set into the headlight fairing. The speedometer was not too accurate, but it appeared to be suffering from some internal bothers (at times the needle would waggle rather wildly and for no apparent reason).

(Continued on Page 44)

NORTON

MANXMAN

SPECIFICATIONS

$1,089

PERFORMANCE

NORTON TEST continued

Although we found the seating and footpeg position ing good, we took an immediate dislike to the handle bars. These seem to bean Englishman's notion of what an American likes - and in the opinion of the entire CYCLE WORLD staff, he missed the mark completely. The bars are rather high, and while the grips are set just about right for angle, they fo~ce the rider to sit up so straight that the wind is a bother. A pair of low, flat bars wouldn't be so comfortable around town, but at the high cruising speeds that are such a delight on the Manxman, the breeze is a .bit stiff for anyone sitting bolt-upright.

While on the subject of cruising, we might also men tion that the Manxman's fuel tank is a trifle inadequate in size for convenience. It holds only 2.5 gallons and that is at least a gallon short of what we would consider the minimum for a touring machine. Here, in what is obviously an attempt to get stylish, they have fitted a tank that runs dry long before either the machine or rider would get tired on a trip ahd have blighted, to some small extent, the many excellent qualities of the Manxman.

Along with the incomparable roadholding, the Manx man possesses a very fine set of brakes. They have finned aluminum-alloy drums of impressive diameter and will pull the machine down to a stop from 100 mph quickly and with an amazing lack of fuss. To top it all off, the pedal and grip pressures required to make even an all-out stop were very low and it is unlikely that better brakes are to be found on any other sports/tour ing motorcycle today.

The clutch was somewhat less attractive. A real "Charles Atlas" grip was needed to operate the release lever and there was a tendency for the clutch to drag even when the lever was pulled back to the limit. More over, when the clutch made engagement, it did so with a series of jerks and grabs. Any attempts at slipping the clutch resulted in quite a lot of shuddering and this hampered our performance tests a great deal. On any high-geared road bike it is necessary to slip the clutch enough to keep the engine speed up while making maximum-effort starts and our test bike's sticky clutch made that very difficult indeed.

The Manxman's gearing has clearly been selected for high speed touring applications. Third and fourth gear ratios are closely spaced and the bike is, in fact, almost as fast in third cog as in top. Most people will not ob ject to the limits imposed on top speed by the gearing, however, for that 4.53 top gear gives effortless cruising. The intermediate ratios are much like top-gear; they give very high speeds, but tend to limit the overall per formance somewhat. Even so, in the kind of service for which the Manxman was obviously intended, they are just right. And, for those who are willing to sacrifice easy cruising for better performance, there is always the possibility of a faster overall drive ratio.

Despite our few critical comments, we were tremen dously impressed by the Norton Manxman. It may not be any great threat at the drag strips, but there is a lot more to motorcycling than that and in its element, which is fast highway cruising, the Manxman has no peer. The ride is comfortable, the brakes are superb and the behavior on any kind of bend, fast or slow, smooth or choppy, is so good that it absolutely beggars description. The feeling of stability under all conditions is simply fantastic. With the Manxman, the Norton company has set a standard to which everyone else will have to work. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

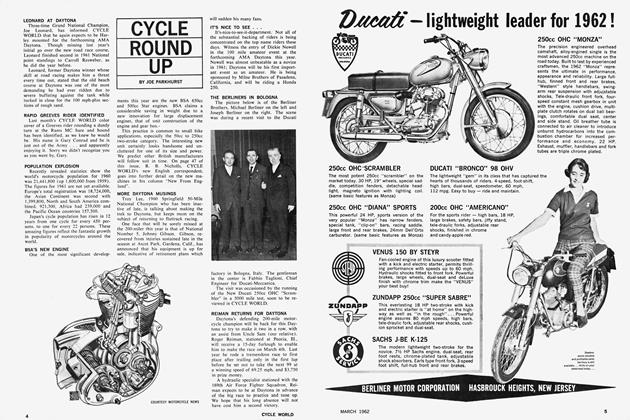

Cycle Round Up

MARCH 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

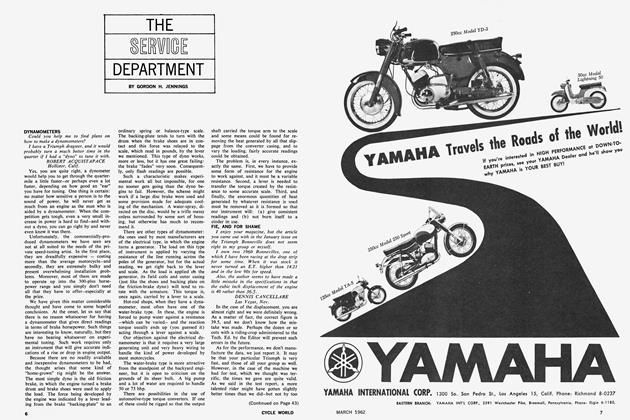

The Service Department

MARCH 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

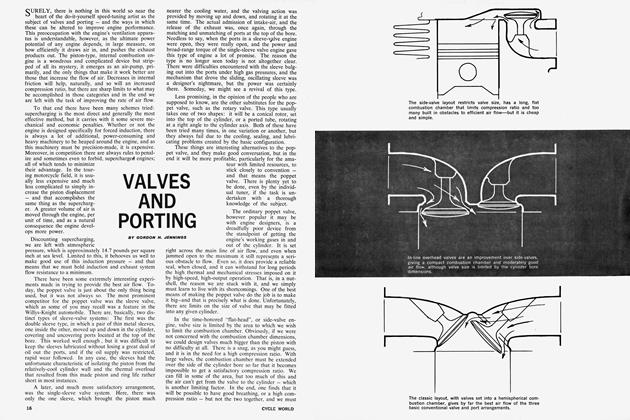

Technical

TechnicalValves And Porting

MARCH 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Travel

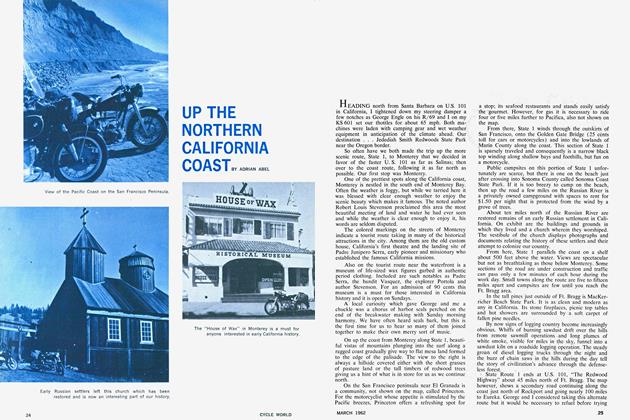

TravelUp the Northern California Coast

MARCH 1962 By Adrian Abel -

A Progress Report

A Progress ReportCycle World Forges Ahead

MARCH 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

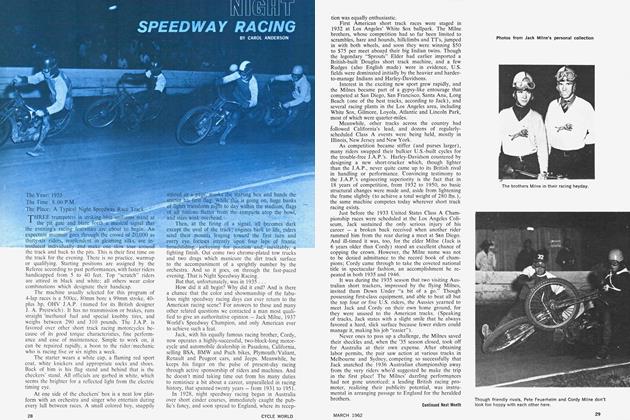

Night Speedway Racing

MARCH 1962 By Carol Anderson