NIGHT SPEEDWAY RACING

CAROL ANDERSON

The Year: 1935

The Time: 8:00 P.M.

The Place: A Typical Night Speedway Race Track

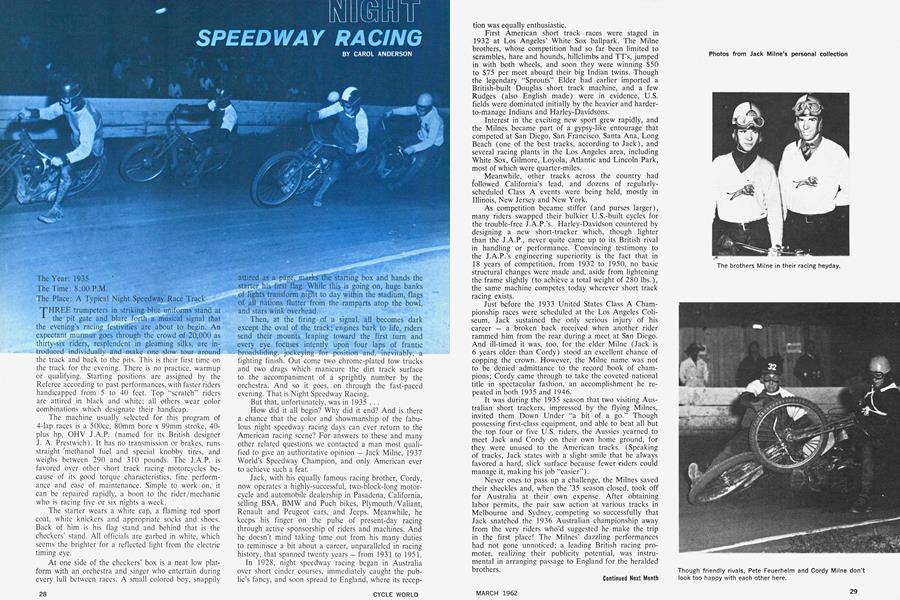

THREE trumpeters in striking blue uniforms stand at the pit gate and blare forth a musical signal that the evening’s racing festivities are about to begin. An expectant murmur goes through the crowd of 20,000 as thirty-six riders, resplendent in gleaming silks, are introduced individually and make one slow tour around the track and back to the pits. This is their first time on the track for the evening. There is no practice, warmup or qualifying. Starting positions are assigned by the Referee according to past performances, with faster riders handicapped from 5 to 40 feet. Top “scratch” riders are attired in black and white; all others wear color combinations which designate their handicap.

The machine usually selected for this program of 4-lap races is a 500cc, 80mm bore x 99mm stroke, 40plus hp, OHV J.A.P. (named for its British designer J. A. Prestwich). It has no transmission or brakes, runs straight 'methanol fuel and special knobby tires, and weighs between 290 and 310 pounds. The J.A.P. is favored over other short track racing motorcycles because of its good torque characteristics, fine performance and ease of maintenance. Simple to work on, it can be repaired rapidly, a boon to the rider/mechanic who is racing five or six nights a week.

The starter wears a white cap, a flaming red sport coat, white knickers and appropriate socks and shoes. Back of him is his flag stand and behind that is the checkers' stand. All officials are garbed in white, which seems the brighter for a reflected light from the electric timing eye.

At one side of the checkers' box is a neat low platform with an orchestra and singer who entertain during every lull between races. A small colored boy, snappily attired as starting box and hands the •~tart~ his first hag.. While this is going on, huge banks çf lights transform p~i~t to day within the stadium, flags of all nations flutter from the .ramparts atop the bowl, and stars wink overhead.

Then, at the firing of a signal, all becomes dark except the oval of the track; engines bark to life, riders send their mounts leaping toward the first turn and every eye focuses intently upon four laps of frantic broadsliding, jockeying for position and, inevitably, a fighting finish. Out come two chrome-plated tow trucks and two drags which manicure the dirt track surface to the accompaniment of a sprightly number by the orchestra. And so it goes, on through the fast-paced evening. That is Night Speedway Racing.

But that, unfortunately, was in 1935 . . .

How did it all begin? Why did it end? And is there a chance that the color and showmanship of the fabulous night speedway racing days can ever return to the American racing scene? For answers to these and many other related questions we contacted a man most qualified to give an authoritative opinion — Jack Milne, 1937 World’s Speedway Champion, and only American ever to achieve such a feat.

Jack, with his equally famous racing brother, Cordy, now operates a highly-successful, two-block-long motorcycle and automobile dealership in Pasadena, California, selling BSA, BMW and Puch bikes, Plymouth/Valiant, Renault and Peugeot cars, and Jeeps. Meanwhile, he keeps -his finger on the pulse of present-day racing through active sponsorship of riders and machines. And he doesn’t mind taking time out from his many duties to reminisce a bit about a career, unparalleled in racing history, that spanned twenty years - from 1931 to 1951.

In 1928, night speedway racing began in Australia over short cinder courses, immediately caught the public’s fancy, and soon spread to England, where its reception was equally enthusiastic.

First American short track races were staged in 1932 at Los Angeles’ White Sox ballpark. The Milne brothers, whose competition had so far been limited to scrambles, hare and hounds, hillclimbs and TT’s, jumped in with both wheels, and soon they were winning $50 to $75 per meet aboard their big Indian twins. Though the legendary “Sprouts” Elder had earlier imported a British-built Douglas short track machine, and a few Rudges (also English made) were in evidence, U.S. fields were dominated initially by the heavier and harderto-manage Indians and Harley-Davidsons.

Interest in the exciting new sport grew rapidly, and the Milnes became part of a gypsy-like entourage that competed at San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Ana, Long Beach (one of the best tracks, according to Jack), and several racing plants in the Los Angeles area, including White Sox, Gilmore, Loyola, Atlantic and Lincoln Park, most of which were quarter-miles.

Meanwhile, other tracks across the country had followed California’s lead, and dozens of regularlyscheduled Class A events were being held, mostly in Illinois, New Jersey and New York.

As competition became stiffer (and purses larger), many riders swapped their bulkier U.S.-built cycles for the trouble-free J.A.P.’s. Harley-Davidson countered by designing a new short-tracker which, though lighter than the J.A.P., never quite came up to its British rival in handling or performance. 'Convincing testimony to the J.A.P.’s engineering superiority is the fact that in 18 years of competition, from 1932 to 1950, no basic structural changes were made and, aside from lightening the frame slightly (to achiève a total weight of 280 lbs.), the same machine competes today wherever short track racing exists.

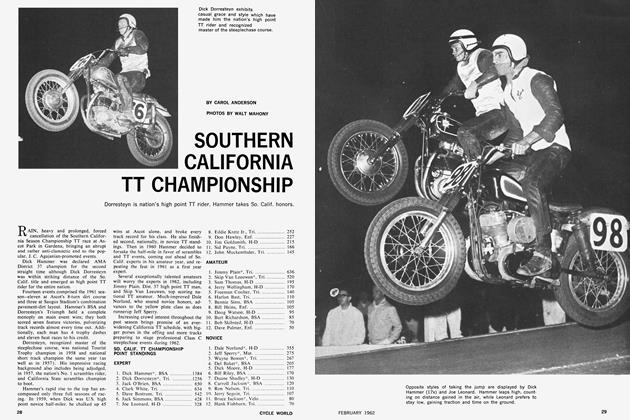

Just before the 1933 United States Class A Championship races were scheduled at the Los Angeles Coliseum, Jack sustained the only serious injury of his career — a broken back received when another rider rammed him from the rear during a meet at San Diego. And ill-timed it was, too, for the elder Milne (Jack is 6 years older than Cordy) stood an excellent chance of copping the crown. However, the Milne name was not to be denied admittance to the record book of champions; Cordy came through to take the coveted national title in spectacular fashion, an accomplishment he repeated in both 1935 and 1946.

It was during the 1935 season that two visiting Australian short trackers, impressed by the flying Milnes, invited them Down Under “a bit of a go.” Though possessing first-class equipment, and able to beat all but the top four or five U.S. riders, the Aussies yearned to meet Jack and Cordy on their own home ground, for they were unused to the American tracks. (Speaking of tracks, Jack states with a slight smile that he always favored a hard, slick surface because fewer -riders could manage it, making his job “easier”).

Never ones to pass up a challenge, the Milnes saved their sheckles and, when the ’35 season closed, took off for Australia at their own expense. After obtaining labor permits, the pair saw action at various tracks in Melbourne and Sydney, competing so successfully that Jack snatched the 1936 Australian championship away from the very riders who’d suggested he make the trip in the first place! The Milnes’ dazzling performances had not gone unnoticed; a leading British racing promoter, realizing their publicity potential, was instrumental in arranging passage to England for the heralded brothers.

Continued Next Month

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

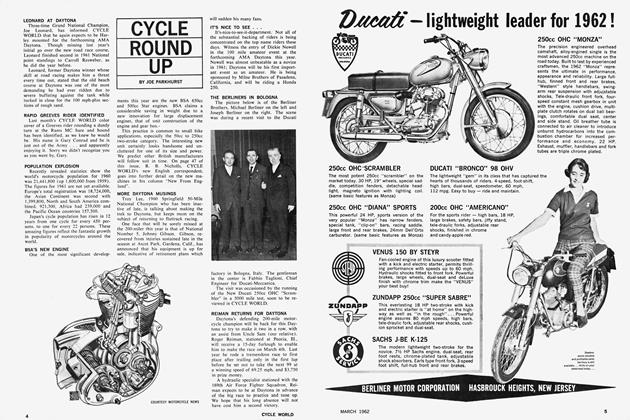

Cycle Round Up

MARCH 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

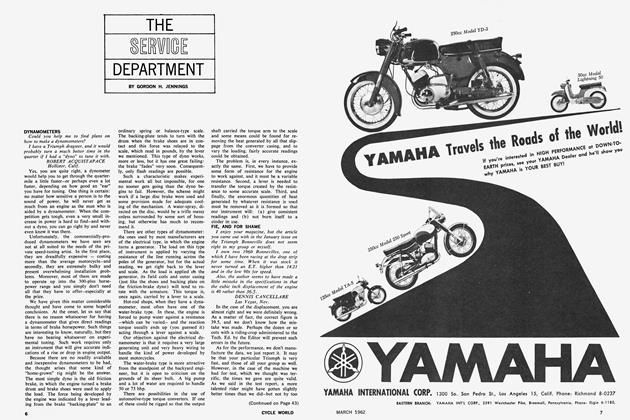

The Service Department

MARCH 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Technical

TechnicalValves And Porting

MARCH 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Travel

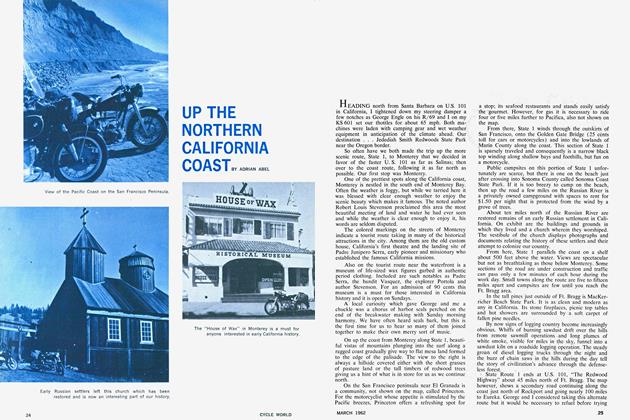

TravelUp the Northern California Coast

MARCH 1962 By Adrian Abel -

A Progress Report

A Progress ReportCycle World Forges Ahead

MARCH 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

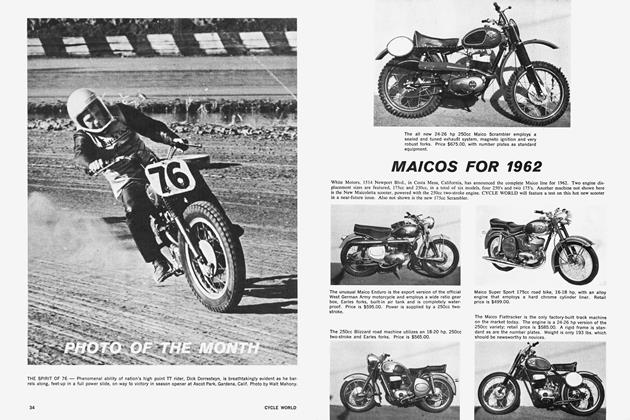

Photo of the Month

MARCH 1962 By Walt Mahony