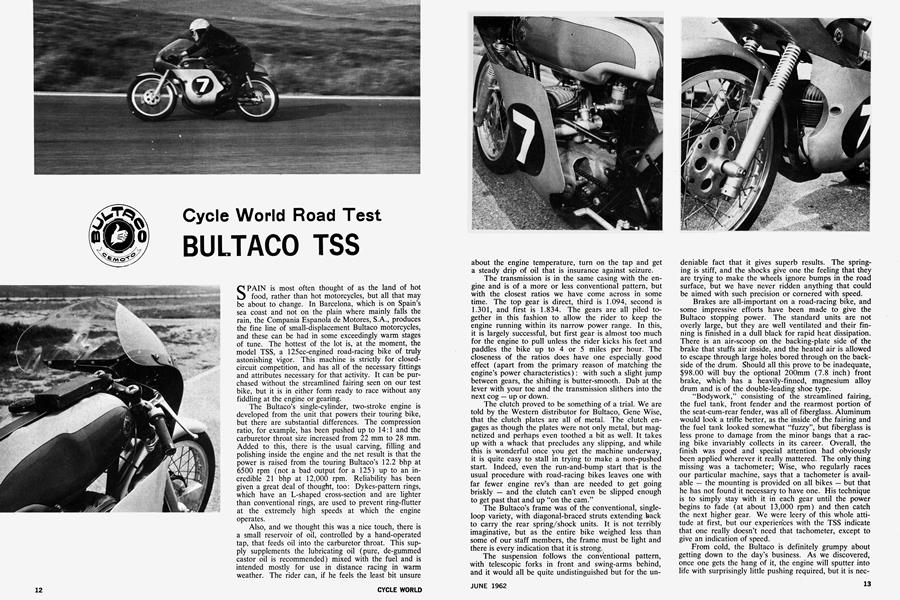

BULTACO TSS

Cycle World Road Test

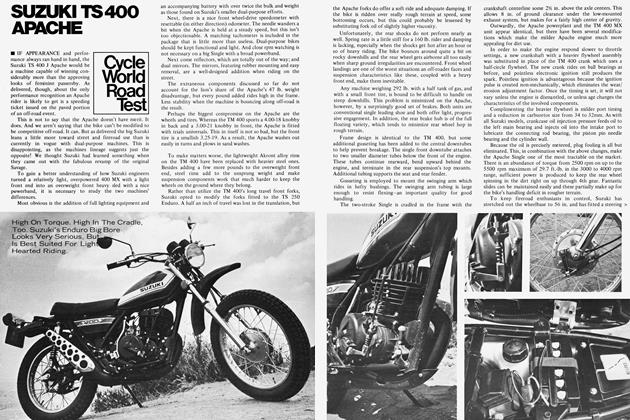

SPAIN is most often thought of as the land of hot food, rather than hot motorcycles, but all that may be about to change. In Barcelona, which is on Spain's sea coast and not on the plain where mainly falls the rain, the Compania Espanola de Motores, S.A., produces the fine line of small-displacement Bultaco motorcycles, and these can be had in some exceedingly warm stages of tune. The hottest of the lot is, at the moment, the model TSS, a 125cc-engined road-racing bike of truly astonishing vigor. This machine is strictly for closed circuit competition, and has all of the necessary fittings and attributes necessary for that activity. It can be pur chased without the streamlined fairing seen on our test bike, but it is in either form ready to race without any fiddling at the engine or gearing.

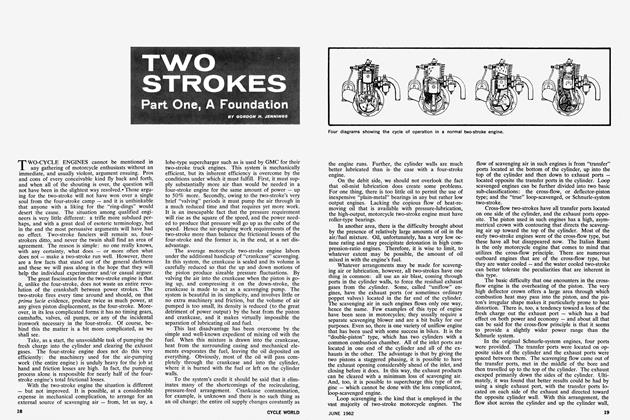

The Bultaco's single-cylinder, two-stroke engine is developed from the unit that powers their touring bike, but there are substantial differences. The compression ratio, for example, has been pushed up to 14:1 and the carburetor throat size increased from 22 mm to 28 mm. Added to this, there is the usual carving, filling and polishing inside the engine and the net result is that the power is raised from the touring Bultaco's 12.2 bhp at 6500 rpm (not a bad output for a 125) up to an in credible 21 bhp at 12,000 rpm. Reliability has been given a great deal of thought, too: Dykes-pattern rings, which have an L-shaped cross-section and are lighter than conventional rings, are used to prevent ring-flutter at the extremely high speeds at which the engine operates.

Also, and we thought this was a nice touch, there is a small reservoir of oil, controlled by a hand-operated tap, that feeds oil into the carburetor throat. This sup ply supplements the lubricating oil (pure, de-gummed castor oil is recommended) mixed with the fuel and is intended mostly for use in distance racing in warm weather. The rider can, if he feels the least bit unsure about the engine temperature, turn on the tap and get a steady drip of oil that is insurance against seizure.

The transmission ig in the same casing with the en gine and is of a more or less conventional pattern, but with the closest ratios we have come across in some time. The top gear is direct, third is 1.094, second is 1.301, and first is 1.834. The gears are all piled to gether in this fashion to allow the rider to keep the engine running within its narrow power range. In this, it is largely successful, but first gear~is almost too much for the engine to pull unless the rider kicks his feet and paddles the bike up to 4 or 5 miles per hour. The closeness of the ratios does have one especially good effect (apart from the primary reason of matching the engine's power characteristics): with such a slight jump between gears, the shifting is butter-smooth. Dab at the lever with your toe and the transmission slithers into the next cog - up or down.

The clutch proved to be something of a trial. We are told by the Western distributor for Bultaco, Gene Wise, that the clutch plates are all of metal. The clutch en gages as though the plates were not only metal, but mag netized and perhaps even toothed a bit as well. It takes up with a whack that precludes any slipping, and while this is wonderful once you get the machine underway, it is quite easy to stall in trying to make a non-pushed start. Indeed, even the run-and-bump start that is the usual procedure with road-racing bikes leaves one with far fewer engine rev's than are needed to get going briskly - and the clutch can't even be slipped enough to get past that and up "on the cam."

The Bultaco's frame was of the conventional, singleloop variety, with diagonal-braced struts extending back to carry the rear spring/shock units. It is not terribly imaginative, but as the entire bike weighed less than some of our staff members, the frame must be light and there is every indication that it is strong.,

The suspension follows the conventional pattern, with telescopic forks in front and swing-arms behind, and it would all be quite undistinguished but for the un deniable fact that it gives superb results. The spring ing is stiff, and the shocks give one the feeling that they are trying to make the wheels ignore bumps in the road surface, but we have never ridden anything that could be aimed with such precision or cornered with speed.

Brakes are all-important on a road-racing bike, and some impressive efforts have been made to give the Bultaco stopping power. The standard units are not overly large, but they are well ventilated and their finning is finished in a dull black for rapid heat dissipation. There is an air-scoop on the backing-plate side of the brake that stuffs air inside, and the heated air is allowed to escape through large holes bored through on the backside of the drum. Should all this prove to be inadequate, $98.00 will buy the optional 200mm (7.8 inch) front brake, which has a heavily-finned, magnesium alloy drum and is of the double-leading shoe type.

“Bodywork,” consisting of the streamlined fairing, the fuel tank, front fender and the rearmost portion of the seat-cum-rear fender, was all of fiberglass. Aluminum would look a trifle better, as the inside of the fairing and the fuel tank looked somewhat “fuzzy”, but fiberglass is less prone to damage from the minor bangs that a racing bike invariably collects in its career. Overall, the finish was good and special attention had obviously been applied wherever it really mattered. The only thing missing was a tachometer; Wise, who regularly races our particular machine, says that a tachometer is available — the mounting is provided on all bikes — but that he has not found it necessary to have one. His technique is to simply stay with it in each gear until the power begins to fade (at about 13,000 rpm) and then catch the next higher gear. We were leery of this whole attitude at first, but our experiences with the TSS indicate that one really doesn’t need that tachometer, except to give an indication of speed.

From cold, the Bultaco is definitely grumpy about getting down to the day’s business. As we discovered, once one gets the hang of it, the engine will sputter into life with surprisingly little pushing required, but it is necessary to coax it along on a “hot” plug until it is thoroughly warm. Then, the switch can be made to a colder, racing plug (Lodge 50-51, or NGK 9E-10E) after which it is all ready to go — but don’t even think about allowing it to idle or the plug will foul. Of course, this is no more than one expects from a “real” racing bike.

Riders of different heights can get tucked in on the TSS, but the taller ones won’t feel any too comfortable. Basically, this is a lightweight machine for lightweight riders and the bigger lads are going to have to pay for their bulk. Even so, our tech, ed., who is a largish lout and not very supple, managed to not only ride the TSS, but to enjoy the experience enormously — as did other staff members of varying sizes and weights. What we are really trying to say is that you taller-than-average types might not be very comfortable on the Bultaco TSS; but until you get off and the muscle spasms hit you, you won’t care a bit.

The TSS being the kind of razzle-dazzle two-wheeler it is, we were forced — very willingly — to take it to a proper race course. Riverside International Raceway was the venue selected (it is close to Los Angeles and is a fine, challenging circuit) and the .weather obliged by being bright and beautiful. Before attempting any acceleration runs, we rode several laps around the road course to get the “feel” of the Bultaco. Getting past the initial awkwardness that comes with any new bike, we began to try a little and soon found that there is more to this 125cc racing than meets the eye.

In the first place, with such a small, highly-tuned engine, one has to learn to use lots of revolutions at all times and to never let one’s speed drop more than is absolutely necessary — you haven’t enough torque to get back up to speed quickly. Owner Wise says that he travels over the bridge in turn-one and down through the “esses” in fourth-gear and doing just about everything the bike has (on a good day, and when he is feeling brave). Then down into third, and finally second, for the awkward and infamous turn-six. Up through the gears, touching fourth briefly, and -then back down to second-cog for the looping turn-seven. All the way up into fourth on the approach to the multi-cambered, deceptive turn-eight hairpin, getting down to first for the hairpin itself, and then down the straight at over 100 mph in fourth. Catch third, and then second around the banked but treacherous turn-nine. Accelerating out, he catches third again just as he exits from turn-nine, and then up the start/finish straight and into fourth for that “hairy” first turn.

Our efforts were not as polished, nor as fast, as those of Wise. We popped over the rise into the firstturn cranking off about 11,500 rpm in third and went flailing through the esses turning a rather gingerly 10,000 rpm in fourth. In turn-six we were too busy to consider how fast we might be going and turn seven, which one approaches over a blind hill, allowed us only about 8000 rpm in second. The turn-eight hair-pin we would rather not even discuss except to say that we managed not to fall down. Turn-nine was taken in the same gear and in roughly the same direction as it is negotiated by Wise, and we even managed to get up about 11,500 rpm (in second gear) out in the middle of the turn.

It was a day that had us cursing our clumsiness, and thankful that the Bultaco is so understanding of our frailties. We will say that this is the only bike we have ever ridden that never felt as though it might be about to deposit us on the pavement. One can get it over at an impossible angle and if you over-do things, it simply runs off of the road; it never slips. The only thing that bothered us was the fact that the machine is so low that when leaned over in a turn, one’s eyes are so near the road that it is hard to see ahead. It sounds ridiculous, but it is true.

In our regular acceleration trials the Bultaco was lost. The very tall first gear and the high power peak made it impossible to get moving — hence, the slow quarter-mile and the funny looking acceleration curve. As the curve indicates, the TSS does not begin to accelerate until the 40 mph point is reached.

Top speed was a different story. The Bultaco made several runs at exactly 102 mph, and while that is not as fast as is claimed by Bultaco’s advertising brochures, it is blistering fast for a 125-class bike. Moreover, owner Wise says that with a little on-the-spot fiddling it will get up to perhaps 108 — and we believe him.

All in all, we think that this is a great little bike. Certainly, one can’t get onto a first-rate racing bike for much less money, and it is not too likely that more fun and excitement can be had at any price. •

BULTACO

TSS

SPECIFICATIONS

$899

PERFORMANCE