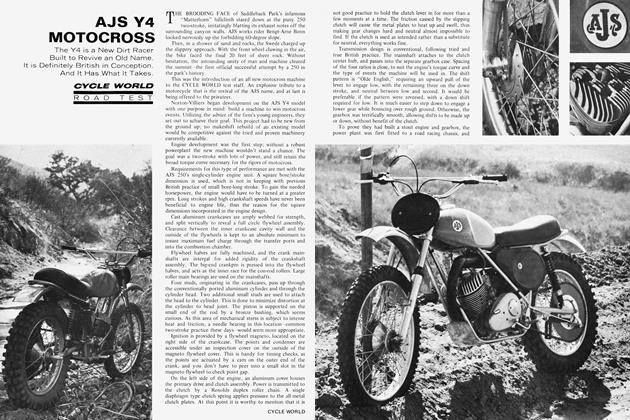

BSA SS-90

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

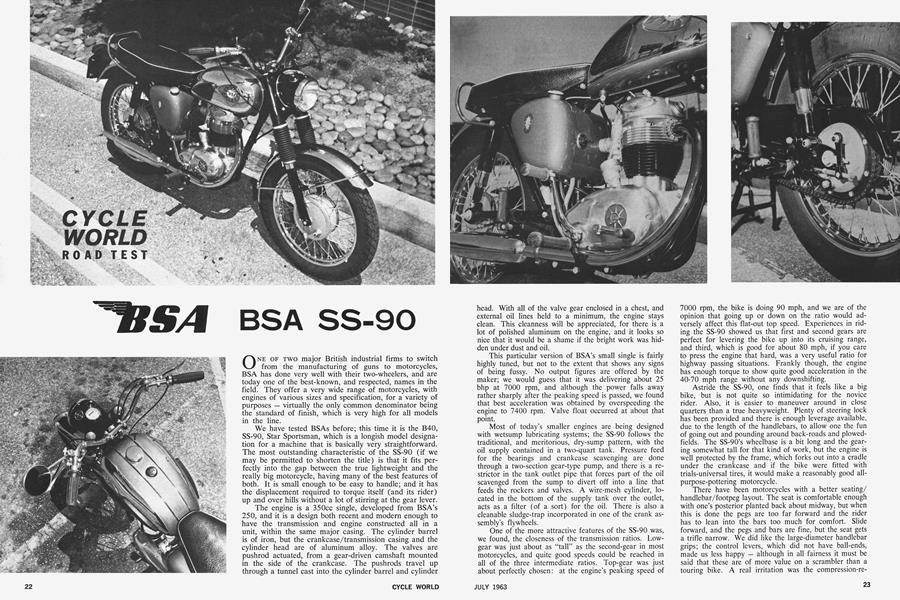

ONE OF TWO major British industrial firms to switch from the manufacturing of guns to motorcycles, BSA has done very well with their two-wheelers, and are today one of the best-known, and respected, names in the field. They offer a very wide range of motorcycles, with engines of various sizes and specification, for a variety of purposes — virtually the only common denominator being the standard of finish, which is very high for all models in the line.

We have tested BS As before; this time it is the B40, SS-90, Star Sportsman, which is a longish model designation for a machine that is basically very straightforward. The most outstanding characteristic of the SS-90 (if we may be permitted to shorten the title) is that it fits perfectly into the gap between the true lightweight and the really big motorcycle, having many of the best features of both. It is small enough to be easy to handle; and it has the displacement required to torque itself (and its rider) up and over hills without a lot of stirring at the gear lever.

The engine is a 350cc single, developed from BS A's 250, and it is a design both recent and modern enough to have the transmission and engine constructed all in a unit, within the same major casing. The cylinder barrel is of iron, but the crankcase/transmission casing and the cylinder head are of aluminum alloy. The valves are pushrod actuated, from a gear-driven camshaft mounted in the side of the crankcase. The pushrods travel up through a tunnel cast into the cylinder barrel and cylinder head. With all of the valve gear enclosed in a chest, and external oil lines held to a minimum, the engine stays clean. This cleanness will be appreciated, for there is a lot of polished aluminum on the engine, and it looks so nice that it would be a shame if the bright work was hidden under dust and oil.

This particular version of BSA's small single is fairly highly tuned, but not to the extent that shows any signs of being fussy. No output figures are offered by the maker; we would guess that it was delivering about 25 bhp at 7000 rpm, and although the power falls away rather sharply after the peaking speed is passed, we found that best acceleration was obtained by overspeeding the engine to 7400 rpm. Valve float occurred at about that point.

Most of today's smaller engines are being designed with wetsump lubricating systems; the SS-90 follows the traditional, and meritorious, dry-sump pattern, with the oil supply contained in a two-quart tank. Pressure feed for the bearings and crankcase scavenging are done through a two-section gear-type pump, and there is a restrictor in the tank outlet pipe that forces part of the oil scavenged from the sump to divert off into a line that feeds the rockers and valves. A wire-mesh cylinder, located in the bottom of the supply tank over the outlet, acts as a filter (of a sort) for the oil. There is also a cleanable sludge-trap incorporated in one of the crank assembly's flywheels.

One of the more attractive features of the SS-90 was, we found, the closeness of the transmission rátios. Lowgear was just about as "tall" as the second-gear in most motorcycles, and quite good speeds could be reached in all of the three intermediate ratios. Top-gear was just about perfectly chosen: at the engine's peaking speed of 7000 rpm, the bike is doing 90 mph, and we are of the opinion that going up or down on the ratio would adversely affect this flat-out top speed. Experiences in riding the SS-90 showed us that first and second gears are perfect for levering the bike up into its cruising range, and third, which is good for about 80 mph, if you care to press the engine that hard, was a very useful ratio for highway passing situations. Frankly though, the engine has enough torque to show quite good acceleration in the 40-70 mph range without any downshifting.

Astride the SS-90, one finds that it feels like a big bike, but is not quite so intimidating for the novice rider. Also, it is easier to maneuver around in close quarters than a true heavyweight. Plenty of steering lock has been provided and there is enough leverage available, due to the length of the handlebars, to allow one the fun of going out and pounding around back-roads and plowedfields. The SS-90's wheelbase is a bit long and the gearing somewhat tall for that kind of work, but the engine is well protected by the frame, which forks out into a cradle under the crankcase and if the bike were fitted with trials-universal tires, it would make a reasonably good allpurpose-pottering motorcycle.

There have been motorcycles with a better seating/ handlebar/footpeg layout. The seat is comfortable enough with one's posterior planted back about midway, but when this is done the pegs are too far forward and the rider has to lean into the bars too much for comfort. Slide forward, and the pegs and bars are fine, but the seat gets a trifle narrow. We did like the large-diameter handlebar grips; the control levers, which did not have ball-ends, made us less happy — although in all fairness it must be said that these are of more value on a scrambler than a touring bike. A real irritation was the compression-release lever, which seemed to have been added as an afterthought in the arranging of controls and was placed where no human finger could ever hope to reach it from the handlebar grip. Better placed and easier to reach were the choke-lever and such things as the stands (there are two: one a two-leg overcenter stand; the other a sideprop).

Kick-starting this medium-big single requires either muscle or technique; we prefer the latter. Like most singles, the best results for the least effort are obtained by bringing it up against compression, then using the compression release to nudge the piston up just past top center, and finally ramming it through briskly. In the case of the SS-90, this gets results. Seldom did the engine take more than two or three kicks before it came to life even when cold; when warm, one relatively gentle poke at the starter-lever would do the job. Our test bike, which may or may not be typical, showed a slight tendency toward flooding, but after we learned not to tackle or choke it to death, no further difficulties were encountered.

Of some assistance in starting the engine was the ignition system employed: a straight battery and coil setup, with a centrifugal advance mechanism for the contact breaker. This provides a good, hot spark and the spark is automatically retarded enough at crank-over speeds to eliminate back-bite. An alternator, mounted inside the primary case and driven from the crankshaft's outboard end, supplies current to charge the battery and for the lighting.

The duplex primary chain is entirely enclosed, and has an adjustable tensioner; the adjuster being exposed when the primary case cover is removed. The clutch adjustment, a set-screw, can be reached by merely removing a small, threaded plug. Oil for the lubrication of the primary chain is carried in the primary drive casing, and there is a metered flow of oil from this case to the rear chain, to keep it in good condition.

About the brakes, little can be said except that they do their job, and do it without shuddering. The leading/ trailing shoe system is entirely conventional, and the combination of the 7-inch drum in front, and 6-inch drum (both of aluminum, with an iron liner) in the rear have enough capacity to handle that which is being asked of them. The action was somewhat spongy, but the pressure requirement was low and they do stop the motorcycle in a very determined fashion.

In the main, the ride and handling characteristics were good. The SS-90 has all of the stability of a big bike, but is easier to toss from side to side down a series of fast S-bends. Also, there is nothing protruding down to trip the bike when it is heeled far over and the front forks do not have any of that curious waggle-waggle that afflict some machines when leaned down for a corner. Indeed, the front forks do an exceptional job all around, and it may be significant of something or another that no steering damper is fitted — or required. The rear suspension is not quite as good. The springing is too stiff, at least for solo riding, and one's progress around bumpy bends, if cornering with any verve at all, is disturbed (the extent depending on one's speed and the roughness of the road) by the rear wheel's distressing habit of "stepping-out" an inch or so with each major bump. Fortunately, those little side-shudders never developed into anything serious enough to drop the machine, but they do tend to make the rider cautious.

It is in the area of finish, and overall sturdiness and quality, that the SS-90 is most impressive. The machine is obviously intended to take a lot of abuse, and to resist the incidental chipping and battering that comes with day-in, day-out use. Chromium-plated surfaces are less likely to lose their luster after long periods of service than paint (the aesthetics are debatable) and, given a modicum of care, the SS-90 will look, and run, like a new motorcycle for a long time after its purchase. Even at the relatively high price, we consider it something of a bargain. Expense is, after all, a function of cost against service and satisfaction obtained, and on that basis the SS-90, with its simple and sturdy "thumper" engine, is very hard to beat.

BSA SS-90 STAR SPORTSMAN

SPECIFICATIONS

$785.00

PERFORMANCE