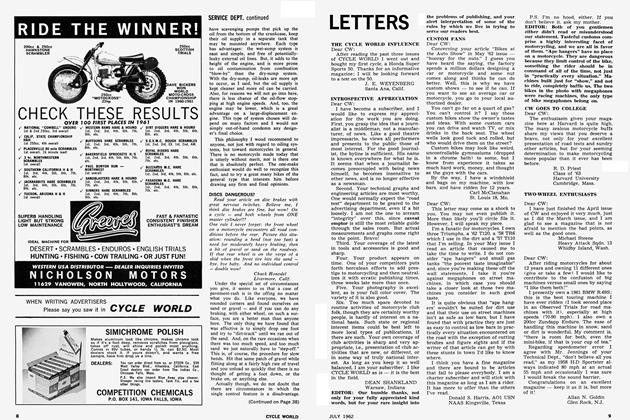

PARILLA SCRAMBLER

Cycle World Road Test

ONE OF THE LEAST ORTHODOX of all the

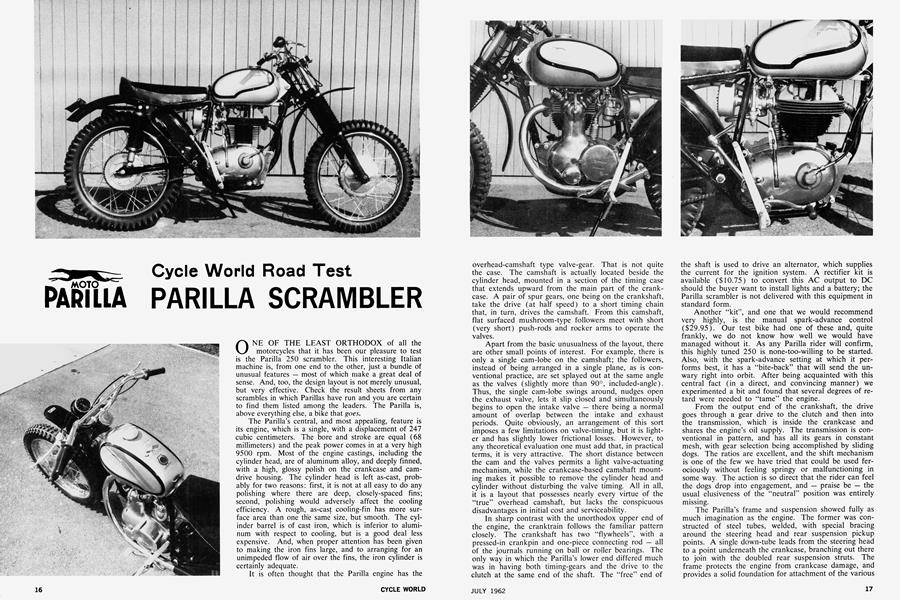

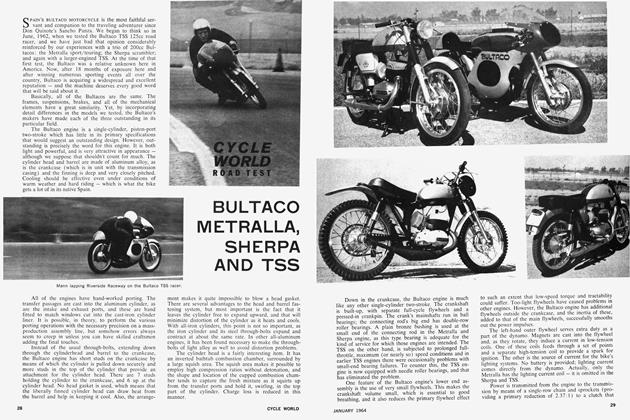

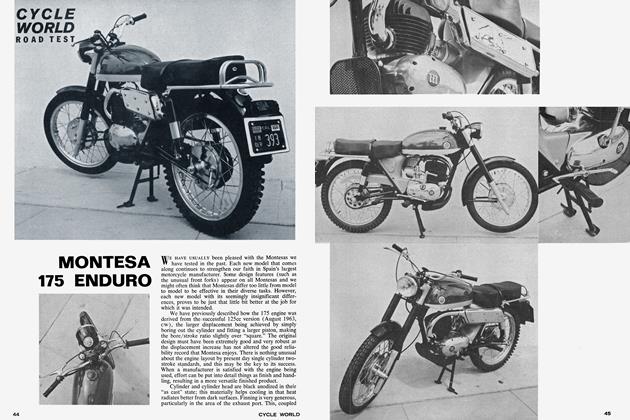

motorcycles that it has been our pleasure to test is the Parilia 250 scrambler. This interesting Italian machine is, from one end to the other, just a bundle of unusual features — most of which make a great deal of sense. And, too, the design layout is not merely unusual, but very effective. Check the result sheets from any scrambles in which Parillas have run and you are certain to find them listed among the leaders. The Parilia is, above everything else, a bike that goes.

The Parilla’s central, and most appealing, feature is its engine, which is a single, with a displacement of 247 cubic centimeters. The bore and stroke are equal (68 millimeters) and the peak power comes in at a very high 9500 rpm. Most of the engine castings, including the cylinder head, are of aluminum alloy, and deeply finned, with a high, glossy polish on the crankcase and camdrive housing. The cylinder head is left as-cast, probably for two reasons: first, it is not at all easy to do any polishing where there are deep, closely-spaced fins; second, polishing would adversely affect the cooling efficiency. A rough, as-cast cooling-fin has more surface area than one the same size, but smooth. The cylinder barrel is of cast iron, which is inferior to aluminum with respect to cooling, but is a good deal less expensive. And, when proper attention has been given to making the iron fins large, and to arranging for an unimpeded flow of air over the fins, the iron cylinder is certainly adequate.

It is often thought that the Parilia engine has the overhead-camshaft type valve-gear. That is not quite the case. The camshaft is actually located beside the cylinder head, mounted in a section of the timing case that extends upward from the main part of the crankcase. A pair of spur gears, one being on the crankshaft, take the drive (at half speed) to a short timing chain that, in turn, drives the camshaft. From this camshaft, flat surfaced mushroom-type followers meet with short (very short) push-rods and rocker arms to operate the valves.

Apart from the basic unusualness of the layout, there are other small points of interest. For example, there is only a single cam-lobe on the camshaft; the followers, instead of being arranged in a single plane, as is conventional practice, are set splayed out at the same angle as the valves (slightly more than 90°, included-angle). Thus, the single cam-lobe swings around, nudges open the exhaust valve, lets it slip closed and simultaneously begins to open the intake valve — there being a normal amount of overlap between the intake and exhaust periods. Quite obviously, an arrangement of this sort imposes a few limitations on valve-timing, but it is lighter and has slightly lower frictional losses. However, to any theoretical evaluation one must add that, in practical terms, it is very attractive. The short distance between the cam and the valves permits a light valve-actuating mechanism, while the crankcase-based camshaft mounting makes it possible to remove the cylinder head and cylinder without disturbing the valve timing. All in all, it is a layout that possesses nearly every virtue of the “true” overhead camshaft, but lacks the conspicuous disadvantages in initial cost and serviceability.

In sharp contrast with the unorthodox upper end of the engine, the cranktrain follows the familiar pattern closely. The crankshaft has two “flywheels”, with a pressed-in crankpin and one-piece connecting rod — all of the journals running on ball or roller bearings. The only way in which the Parilla’s lower end differed much was in having both timing-gears and the drive to the clutch at the same end of the shaft. The “free” end of the shaft is used to drive an alternator, which supplies the current for the ignition system. A rectifier kit is available ($10.75) to convert this AC output to DC should the buyer want to install lights and a battery; the Parilia scrambler is not delivered with this equipment in standard form.

Another “kit”, and one that we would recommend very highly, is the manual spark-advance control ($29.95). Our test bike had one of these and, quite frankly, we do not know how well we would have managed without it. As any Parilia rider will confirm, this highly tuned 250 is none-too-willing to be started. Also, with the spark-advance setting at which it performs best, it has a “bite-back” that will send the unwary right into orbit. After being acquainted with this central fact (in a direct, and convincing manner) we experimented a bit and found that several degrees of retard were needed to “tame” the engine.

From the output end of the crankshaft, the drive goes through a gear drive to the clutch and then into the transmission, which is inside the crankcase and shares the engine’s oil supply. The transmission is conventional in pattern, and has all its gears in constant mesh, with gear selection being accomplished by sliding dogs. The ratios are excellent, and the shift mechanism is one of the few we have tried that could be used ferociously without feeling springy or malfunctioning in some way. The action is so direct that the rider can feel the dogs drop into engagement, and — praise be — the usual elusiveness of the “neutral” position was entirely missing.

The Parilla’s frame and suspension showed fully as much imagination as the engine. The former was constructed of steel tubes, welded, with special bracing around the steering head and rear suspension pickup points. A single down-tube leads from the steering head to a point underneath the crankcase, branching out there to join with the doubled rear suspension struts. The frame protects the engine from crankcase damage, and provides a solid foundation for attachment of the various mechanical elements. We particularly liked the widebased mounting for the rear-suspension’s swing arms. Rigidity at this point is essential for good handling.

The front suspension is of special interest. Basically, it is another of the almost universally used telescopicforks, but with some departures from the usual layout that deserve mention. Instead of being fabricated from steel tubing, the forks are of aluminum alloy — with a very neat-looking black “crinkle” finish. These aluminum “legs” house oil-filled dampers and coil springs and at the top of each leg is a knob, which controls the amount of damping action. This is very convenient: just set the knobs for the damping that conditions require and plunge ahead.

Insofar as the Parilla’s brakes are concerned, little can be said except that they are large, have aluminum finning, give smooth stopping under all conditions that we encountered, and are in every way more than could conceivably be required to stop the machine.

Seating and controls location on a scrambler are most important, and the Parilia scores very well in this respect. The seat is fairly short and wide, and is covered with a suede leather that gives an unsurpassed grip on one’s hindside. The handlebars and footpegs are out there at just the right distance and even the knee-notches in the fuel tank are really where they belong. The footpegs have the added advantage of heavily-braced mountings and the pegs will fold upward. We have only a single adverse comment to make: the kick-start, lever (which folds, too) is placed so that at the bottom of its swing, the rider’s foot is brought into vigorous contact with the peg mounting. Until one learns to kick slightly “slew-footed,” those raps on the top of the foot really smart.

While we may complain somewhat about the difficulties encountered in starting the Parilia, it must be admitted that the struggle is well worthwhile. This is a 250 with bags of power, as long as it is kept turning briskly, and it hauls along through the rough at a very exciting pace. Our impression of the Parilia was that it is, heart and soul, a scrambler. Not necessarily an enduro machine, nor one for trials, but a high-speed scrambler, pure and simple. With such a highly-tuned engine, it gets badly bogged-down in sand; there just isn’t the torque to come chuffing through such soft going. On the other hand, get it out where the engine can be cranked-on tight and it will really fly. For the average scrambles circuit, it has characteristics that make it outstanding.

Its handling at high speed, over bad surfaces, is very good. The Parilia can be dropped over and powered through a dirt-surfaced turn like the best “flat-track” machines and in that kind of going, not many 250cc bikes can stay with it. By and large, its handling and power characteristics make it the machine for the rider who likes a wild, 9000-rpm-and-banzai scrambles mount.

It is interesting to note that this very same bike, with the simple addition of low, “clip on” type handlebars and another exhaust system, is being raced with a large degree of success in road races all over the country. This in itself is an unusual accomplishment for a bike designed primarily for off-the-road work.

Another facet of the Parilia that will appeal to many cyclists is the extreme variety of gear ratios that are available which make it one of the most versatile 250cc machines around.

Frank Cooper Motors in Los Angeles arranged for our test machine which was tuned by Shell Motors in Lynwood, California, headquarters for Guy Lewis III, a Parilia competitor of note.

Completely apart from performance considerations, the Parilia generates a lot of enthusiasm just on appearance. The neat, silver-and-black tank (held on by straps and removable in a couple of minutes), the black frame and fenders and the profusion of polished aluminum are well-near irresistible. Then too, there are things like the remote-float TT-pattern Dellorto carburetor and rubber-mounted, 10,000-rpm tachometer, and those do not go unnoticed or unappreciated. Hard-starting or not, the Parilia is a machine that demands consideration if you are in the market for a new scrambler.

PARILLA

250 SCRAMBLER

SPECIFICATIONS

$784.00