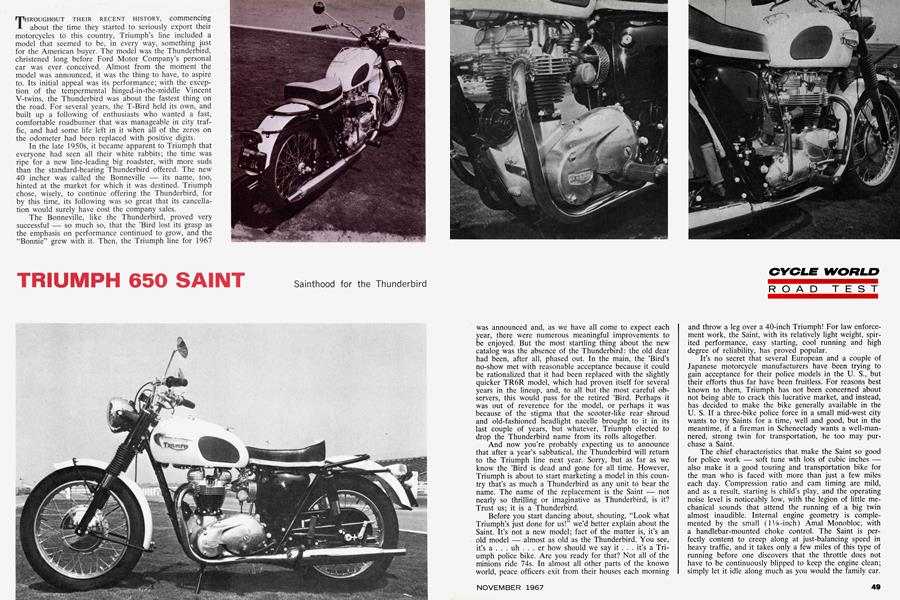

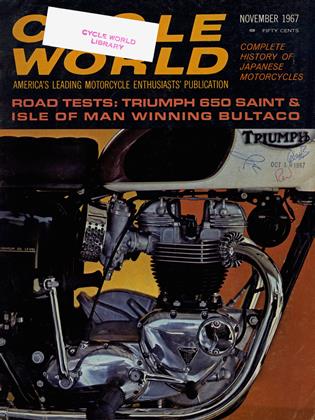

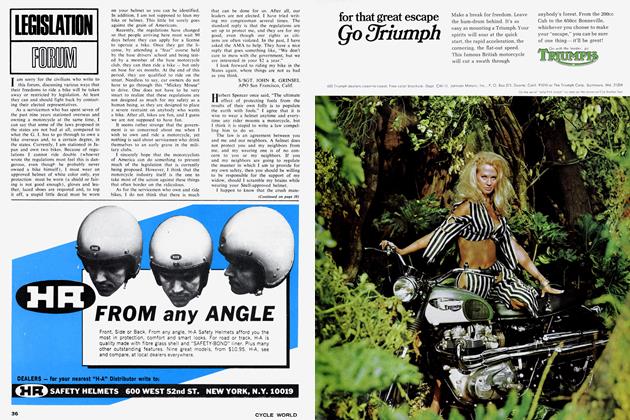

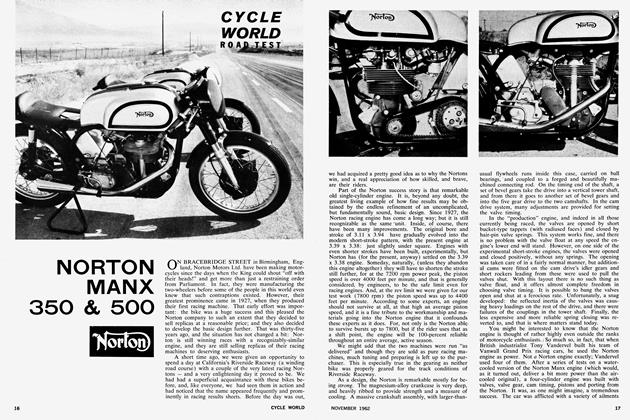

TRIUMPH 650 SAINT

Sainthood for the Thunderbird

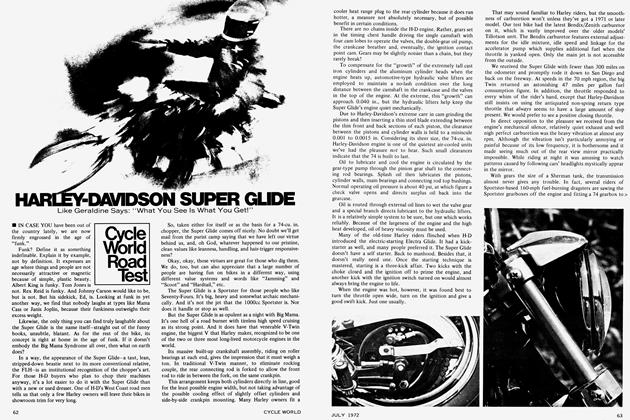

THROUGHOUT THEIR RECENT HISTORY, commencing about the time they started to seriously export their motorcycles to this country, Triumph's line included a model that seemed to be, in every way, something just for the American buyer. The model was the Thunderbird, christened long before Ford Motor Company's personal car was ever conceived. Almost from the moment the model was announced, it was the thing to have, to aspire to. Its initial appeal was its performance; with the exception of the tempermental hinged-in-the-middle Vincent V-twins, the Thunderbird was about the fastest thing on the road. For several years, the T-Bird held its own, and built up a following of enthusiasts who wanted a fast, comfortable roadburner that was manageable in city traffic, and had some life left in it when all of the zeros on the odometer had been replaced with positive digits.

In the late 1950s, it became apparent to Triumph that everyone had seen all their white rabbits; the time was ripe for a new line-leading big roadster, with more suds than the standard-bearing Thunderbird offered. The new 40 incher was called the Bonneville — its name, too, hinted at the market for which it was destined. Triumph chose, wisely, to continue offering the Thunderbird, for by this time, its following was so great that its cancellation would surely have cost the company sales.

The Bonneville, like the Thunderbird, proved very successful — so much so, that the 'Bird lost its grasp as the emphasis on performance continued to grow, and the "Bonnie" grew with it. Then, the Triumph line for 1967 was announced and, as we have all come to expect each year, there were numerous meaningful improvements to be enjoyed. But the most startling thing about the new catalog was the absence of the Thunderbird: the old dear had been, after all, phased out. In the main, the 'Bird's no-show met with reasonable acceptance because it could be rationalized that it had been replaced with the slightly quicker TR6R model, which had proven itself for several years in the lineup, and, to all but the most careful observers, this would pass for the retired 'Bird. Perhaps it was out of reverence for the model, or perhaps it was because of the stigma that the scooter-like rear shroud and old-fashioned headlight nacelle brought to it in its last couple of years, but whatever, Triumph elected to drop the Thunderbird name from its rolls altogether.

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

And now you're probably expecting us to announce that after a year's sabbatical, the Thunderbird will return to the Triumph line next year. Sorry, but as far as we know the 'Bird is dead and gone for all time. However, Triumph is about to start marketing a model in this country that's as much a Thunderbird as any unit to bear the name. The name of the replacement is the Saint — not nearly so thrilling or imaginative as Thunderbird, is it? Trust us; it is a Thunderbird.

Before you start dancing about, shouting, "Look what Triumph's just done for us!" we'd better explain about the Saint. It's not a new model; fact of the matter is, it's an old model — almost as old as the Thunderbird. You see, it's a ... uh ... er how should we say it . . . it's a Triumph police bike. Are you ready for that? Not all of the minions ride 74s. In almost all other parts of the known world, peace officers exit from their houses each morning

and throw a leg over a 40-inch Triumph! For law enforcement work, the Saint, with its relatively light weight, spirited performance, easy starting, cool running and high degree of reliability, has proved popular.

It's no secret that several European and a couple of Japanese motorcycle manufacturers have been trying to gain acceptance for their police models in the U. S., but their efforts thus far have been fruitless. For reasons best known to them, Triumph has not been concerned about not being able to crack this lucrative market, and instead, has decided to make the bike generally available in the U. S. If a three-bike police force in a small mid-west city wants to try Saints for a time, well and good, but in the meantime, if a fireman in Schenectady wants a well-mannered, strong twin for transportation, he too may purchase a Saint.

The chief characteristics that make the Saint so good for police work — soft tune wth lots of cubic inches — also make it a good touring and transportation bike for the man who is faced with more than just a few miles each day. Compression ratio and cam timing are mild, and as a result, starting is child's play, and the operating noise level is noticeably low, with the legion of little mechanical sounds that attend the running of a big twin almost inaudible. Internal engine geometry is complemented by the small (l!/s-inch) Amal Monobloc, with a handlebar-mounted choke control. The Saint is perfectly content to creep along at just-balancing speed in heavy traffic, and it takes only a few miles of this type of running before one discovers that the throttle does not have to be continuously blipped to keep the engine clean; simply let it idle along much as you would the family car. The small choke size also simplifies the starting drill in that the engine prefers to be a tad wet, cold or hot. Open the fuel cocks, close the choke, crack the throttle and kick it through, and a one-prod start is assured each time.

The Saint's frame is the standard item found 01 any of the current Triumph 650s, a single loop type with sturdy forgings used for the major junctions. To the devotee of the super-triangulated, double-loop all-welded skeleton, the Triumph component looks like something you'd encourage your mother-in-law to hot-lap with on the Isle of Man. The appearance is deceptive; the Saint, like other recent Triumphs we've tested, is a stable handler, devoid of pitching and yawing, even when bent hard into bumpy turns. In addition to being extra stout, the frame employs two other features that aid its stability: head angle is shallow, contributing to high-speed stability; and the hefty swing arm is pivoted at four points with the outer two located at the extreme frame width, and as a result, the rear end absolutely refuses to flex. Suspension is typical of what we've come to expect of the marque in recent years. The rear spring-shocks are the ubiquitous and always excellent Girlings. The front forks are, of course, Triumph's own, and must qualify as some of the best production units available. Compression and rebound damping cannot be faulted, and the pinch bolts on the base bridge and the two cinch bolts on each axle cap keep the legs in accurate and constant relationship, even under severe sideloading.

The Saint's brakes, like its suspension, are characteristic of Triumph's offerings in recent years and are predictably good. The rear stopper is a no-frills, cast iron type, with a single-leading-shoe arrangement that is rod actuated. For anything short of panic stops, it will pull the motorcycle down swiftly and comfortably, and it takes more than a few repeated stops before fade can be detected. The front unit is also cast iron, housed, in this case, within a full-width hub. Although it is unvented, it handles heat well, owing in part to being cast iron, and handles its chores confidently and smoothly without a trace of shudder. With regard to the sophisticated brakes that are currently available on many touring bikes, the Triumph units are a bit old-hat; however, their excellent performance cannot be disregarded, and for anything short of all-out racing, they are uncommonly good.

Rider comfort is a major consideration for the Saint, and not surprisingly so when it is considered that the bike is intended to be ridden every day for a full work shift. The strange looking half-seat becomes even stranger in appearance with its short ridge across the back, but one must "sit" the bike for a couple of hours before the design can be appreciated. As a solo saddle, it's the best. As with a well-designed automobile bucket seat, the Saint's platform keeps the rider sitting erect so that the spine, and not the fatigable muscles, carries the bulk of the load of the upper body. The rear ridge prevents the hips from rolling back, and consequently keeps the spine

from bowing. We'll give odds that Triumph enlisted some outside aid in designing this orthopedic device. And we thought that their new twinseat was good! It goes without saying, though, that the Saint is not outfitted for a passenger. A pillion pad could be added to provide minimal comfort to a second occupant for short distances, and a set of pillion pegs are fitted to the bike, but we would strongly advise against an invitation being extended to anyone one does not wish to discourage from the sport. For the loner who would fit a luggage rack for campout touring, or for the commuter who fits one to which he can secure a briefcase, the Saint's arrangement is good, providing all sorts of room on which to place things. But for the girl you're about to propose to . . ! If two-up comfort is essential, it will be necessary to purchase a Triumph twinseat and slip it on in place of the solo model — they use the same attachment scheme of hinges and pull lock.

The handlebars and foot controls coordinate nicely with the seat to keep the rider upright and forever comfortable. Both the hand and the foot controls require reasonable amounts of pressure, and at no time does manipulation come close to being a chore. The bars fitted to the Saint are a wide, moderately pulled back pair that are carried in a rubber-mounted pair of short risers. When maneuvering the bike in and out of the garage, they feel as though they are not attached to anything in particular. Underway, they are another matter, feeling as positive as if they were rigidly mounted, but without acting as a transmission medium for engine and road vibrations.

The Saint's electrics are better than good, and the headlamp beam leaps well down the road ahead of the bike. The automotive type paired horns are the strongest we've seen — or heard — on any motorcycle, and what a pleasure it is to ride a motorcycle with a voice that will urge sleepy-brained motorists back into their own freeway lanes. We strongly hope that some accessory distributor in this country will offer these one day soon, for they are not only stout, but each unit is the size of the regular "peep-peep" type horn that is found on most road bikes.

The Saint's finish is excellent. Welds are clean, castings are superb, polish is lustrous, chrome is brilliant and paint is without flaw. The paint is probably the most outstanding physical feature of the motorcycle — unmarred, untrimmed white on tank and fenders. In the telling, this might not seem to be so much, but in the flesh, it becomes startling.

At first encounter, with its odd looking seat, one knows instinctively that there is something different about the Saint. As we rode it about the city, we were regarded with suspicious stares from other motorcyclists; and ticketwriting highway patrolmen would momentarily forget their business and gape longingly as the Saint whispered by, its rider sitting erect and refreshed.

Triumph broke some hearts when they discontinued the Thunderbird, but they're going to patch those up and win a few more in the bargain with their Saint. ■

TRIUMPH

650 SAINT

$1299