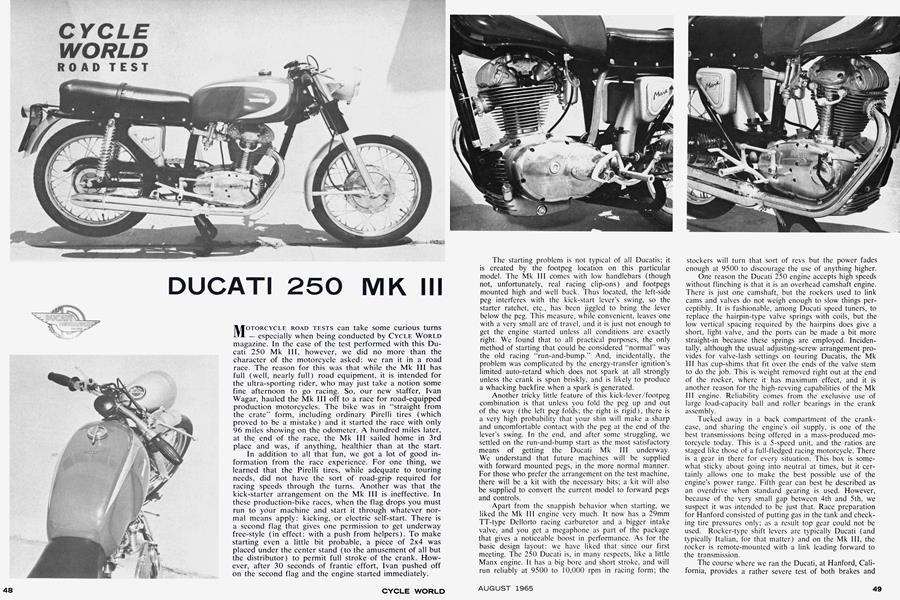

DUCATI 250 MK III

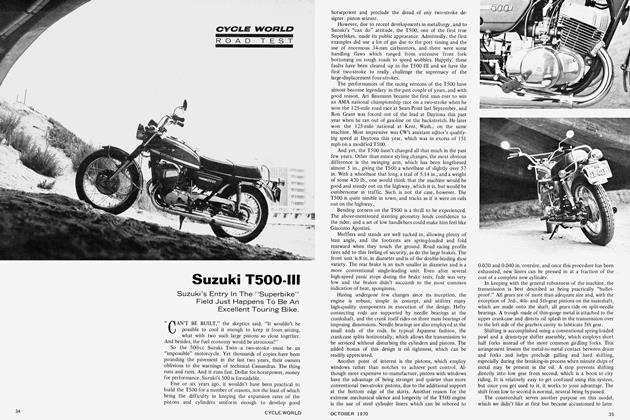

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

MOTORCYCLE ROAD TESTS can take some curious turns — especially when being conducted by CYCLE WORLD magazine. In the case of the test performed with this Ducati 250 Mk III, however, we did no more than the character of the motorcycle asked: we ran it in a road race. The reason for this was that while the Mk III has full (well, nearly full) road equipment, it is intended for the ultra-sporting rider, who may just take a notion some fine afternoon to go racing. So, our new staffer, Ivan Wagar, hauled the Mk III off to a race for road-equipped production motorcycles. The bike was in "straight from the crate" form, including ordinary Pirelli tires (which proved to be a mistake) and it started the race with only 96 miles showing on the odometer. A hundred miles later, at the end of the race, the Mk III sailed home in 3rd place and was, if anything, healthier than at the start.

In addition to all that fun, we got a lot of good information from the race experience. For one thing, we learned that the Pirelli tires, while adequate to touring needs, did not have the sort of road-grip required for racing speeds through the turns. Another was that the kick-starter arrangement on the Mk III is ineffective. In these production-bike races, when the flag drops you must run to your machine and start it through whatever normal means apply: kicking, or electric self-start. There is a second flag that gives one permission to get underway free-style (in effect: with a push from helpers). To make starting even a little bit probable, a piece of 2x4 was placed under the center stand (to the amusement of all but the distributor) to permit full stroke of the crank. However, after 30 seconds of frantic effort, Ivan pushed off on the second flag and the engine started immediately.

The starting problem is not typical of all Ducatis; it is created by the footpeg location on this particular model. The Mk III comes with low handlebars (though not, unfortunately, real racing clip-ons) and footpegs mounted high and well back. Thus located, the left-side peg interferes with the kick-start lever's swing, so the starter ratchet, etc., has been jiggled to bring the lever below the peg. This measure, while convenient, leaves one with a very small arc of travel, and it is just not enough to get the engine started unless all conditions are exactly right. We found that to all practical purposes, the only method of starting that could be considered "normar was the old racing "run-and-bump." And, incidentally, the problem was complicated by the energy-transfer ignition's limited auto-retard which does not spark at all strongly unless the crank is spun briskly, and is likely to produce a whacking backfire when a spark is generated.

Another tricky little feature of this kick-lever/footpeg combination is that unless you fold the peg up and out of the way (the left peg folds; the right is rigid), there is a very high probability that your shin will make a sharp and uncomfortable contact with the peg at the end of the lever's swing. In the end, and after some struggling, we settled on the run-and-bump start as the most satisfactory means of getting the Ducati Mk III underway. We understand that future machines will be supplied with forward mounted pegs, in the more normal manner. For those who prefer the arrangement on the test machine, there will be a kit with the necessary bits; a kit will also be supplied to convert the current model to forward pegs and controls.

Apart from the snappish behavior when starting, we liked the Mk III engine very much. It now has a 29mm TT-type Dellorto racing carburetor and a bigger intake valve, and you get a megaphone as part of the package that gives a noticeable boost in performance. As for the basic design layout: we have liked that since our first meeting. The 250 Ducati is, in many respects, like a little Manx engine. It has a big bore and short stroke, and will run reliably at 9500 to 10,000 rpm in racing form; the stockers will turn that sort of revs but the power fades enough at 9500 to discourage the use of anything higher.

One reason the Ducati 250 engine accepts high speeds without flinching is that it is an overhead camshaft engine. There is just one camshaft, but the rockers used to link cams and valves do not weigh enough to slow things perceptibly. It is fashionable, among Ducati speed tuners, to replace the hairpin-type valve springs with coils, but the low vertical spacing required by the hairpins does give a short, light valve, and the ports can be made a bit more straight-in because these springs are employed. Incidentally, although the usual adjusting-screw arrangement provides for valve-lash settings on touring Ducatis, the Mk III has cup-shims that fit over the ends of the valve stem to do the job. This is weight removed right out at the end of the rocker, where it has maximum effect, and it is another reason for the high-revving capabilities of the Mk III engine. Reliability comes from the exclusive use of large load-capacity ball and roller bearings in the crank assembly.

Tucked away in a back compartment of the crankcase, and sharing the engine's oil supply, is one of the best transmissions being offered in a mass-produced motorcycle today. This is a 5-speed unit, and the ratios are staged like those of a full-fledged racing motorcycle. There is a gear in there for every situation. This box is somewhat sticky about going into neutral at times, but it certainly allows one to make the best possible use of the engine's power range. Fifth gear can best be described as an overdrive when standard gearing is used. However, because of the very small gap between 4th and 5th, we suspect it was intended to be just that. Race preparation for Hanford consisted of putting gas in the tank and checking tire pressures only; as a result top gear could not be used. Rocker-type shift levers are typically Ducati (and typically Italian, for that matter) and on the Mk III, the rocker is remote-mounted with a link leading forward to the transmission.

The course where we ran the Ducati, at Hanford, California, provides a rather severe test of both brakes and handling, and the Mk III scored well in these areas. Actually, the course was too slippery to permit any ear-'ole style cornering, but it is also quite bumpy (we seem to have caught the course owners somewhere between plowing and planting) and the bumps did not affect the bike unduly. The brakes, which were worked hard, were excellent. Anyone going racing seriously could make them run cooler by opening the "scoops" in the front-brake backing plate. These are cast solid and have some dummy slots in them that admit nothing to the inside of the drum.

The Mk III almost has full road equipment: lights and a muffler; but no horn. Perhaps it is intended that one should shout warnings instead of sounding the non-existent horn. Actually, as there is no battery on this model, it may not be possible to have a horn.

One item in the Ducati Mk Ill's electrics gave us a few moments of pondering. It is a small switch connected in parallel with the ignition system, and if the taillight burns out, you must reach back on the rear fender and flip this switch to direct ground before the sparks return. Sometimes even when we know, we do not understand.

Whatever else can be said of the Ducati Mk III, it was great fun to ride. We would have preferred genuine clip-on bars to the droopy flat bars fitted, but the existing setup makes it easy to switch to the higher bars most people like. The seat was too hard and narrow, but the riding position was very good if you like the stretched-out semi-racing crouch — and we do. We also liked the big, knee-notched fuel tank, with its quick-release flip-up filler cap. There was a 150 mph speedometer, which gave wildly optimistic readings, and a built-in odometer that also had a tendency to get ahead of itself. The tachometer, which (like the megaphone) comes with the machine but is not installed, was as good as the speedo was bad. It has a large, easily-read dial — marked up to a realistic 10,000 rpm — and will tell you just what the engine is doing at any given moment. •

Editor's footnote: Bob Blair of ZDS motors has just returned from the Ducati factory and tells us that Dr. Montano is going to look into the kick-starter problem personally.

DUCATI

MK III

SPECI FICATIONS

$729

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue