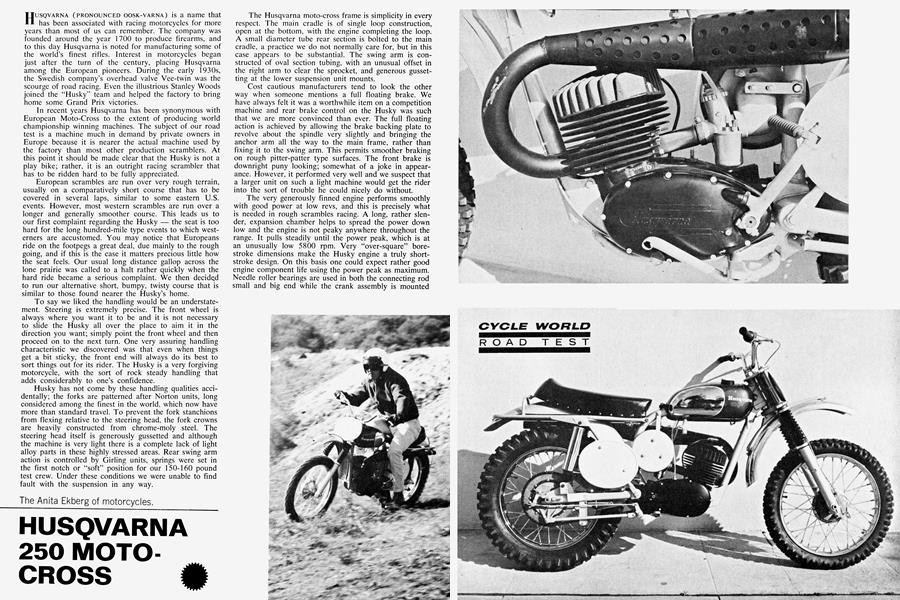

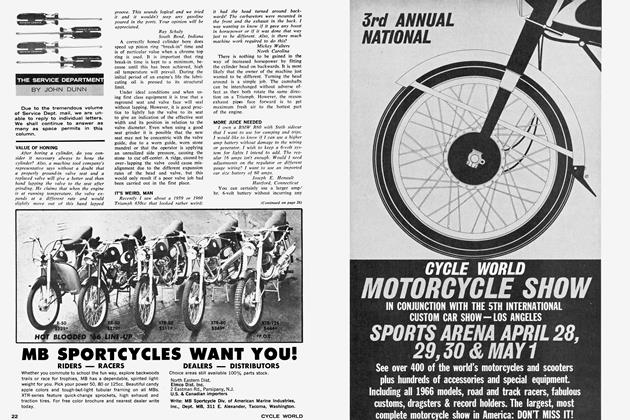

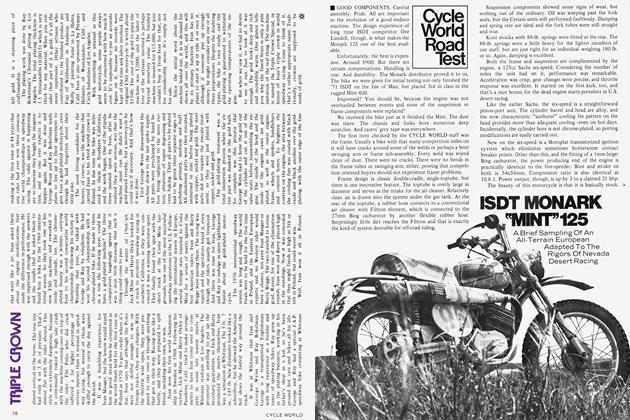

HUSQVARNA 250 MOTO-CROSS

The Anita Ekberg of motorcycles.

HUSQVARNA (PRONOUNCED OOSK-VARNA) is a name that has been associated with racing motorcycles for more years than most of us can remember. The company was founded around the year 1700 to produce firearms, and to this day Husqvarna is noted for manufacturing some of the world's finest rifles. Interest in motorcycles began just after the turn of the century, placing Husqvarna among the European pioneers. During the early 1930s, the Swedish company's overhead valve Vee-twin was the scourge of road racing. Even the illustrious Stanley Woods joined the "Husky" team and helped the factory to bring home some Grand Prix victories.

In recent years Husqvarna has been synonymous with European Moto-Cross to the extent of producing world championship winning machines. The subject of our road test is a machine much in demand by private owners in Europe because it is nearer the actual machine used by the factory than most other production scramblers. At this point it should be made clear that the Husky is not a play bike; rather, it is an outright racing scrambler that has to be ridden hard to be fully appreciated.

European scrambles are run over very rough terrain, usually on a comparatively short course that has to be covered in several laps, similar to some eastern U.S. events. However, most western scrambles are run over a longer and generally smoother course. This leads us to our first complaint regarding the Husky the seat is too hard for the long hundred-mile type events to which westerners are accustomed. You may notice that Europeans ride on the footpegs a great deal, due mainly to the rough going, and if this is the case it matters precious little how the seat feels. Our usual long distance gallop across the lone prairie was called to a halt rather quickly when the hard ride became a serious complaint. We then decided to run our alternative short, bumpy, twisty course that is similar to those found nearer the Husky's home.

To say we liked the handling would be an understatement. Steering is extremely precise. The front wheel is always where you want it to be and it is not necessary to slide the Husky all over the place to aim it in the direction you want; simply point the front wheel and then proceed on to the next turn. One very assuring handling characteristic we discovered was that even when things get a bit sticky, the front end will always do its best to sort things out for its rider. The Husky is a very forgiving motorcycle, with the sort of rock steady handling that adds considerably to one's confidence.

Husky has not come by these handling qualities accidentally; the forks are patterned after Norton units, long considered among the finest in the world, which now have more than standard travel. To prevent the fork stanchions from flexing relative to the steering head, the fork crowns are heavily constructed from chrome-moly steel. The steering head itself is generously gussetted and although the machine is very light there is a complete lack of light alloy parts in these highly stressed areas. Rear swing arm action is controlled by Girling units, springs were set in the first notch or "soft" position for our 150-160 pound test crew. Under these conditions we were unable to find fault with the suspension in any way.

The Husqvarna moto-cross frame is simplicity in every respect. The main cradle is of single loop construction, open at the bottom, with the engine completing the loop. A small diameter tube rear section is bolted to the main cradle, a practice we do not normally care for, but in this case appears to be substantial. The swing arm is constructed of oval section tubing, with an unusual offset in the right arm to clear the sprocket, and generous gussetting at the lower suspension unit mounts.

Cost cautious manufacturers tend to look the other way when someone mentions a full floating brake. We have always felt it was a worthwhile item on a competition machine and rear brake control on the Husky was such that we are more convinced than ever. The full floating action is achieved by allowing the brake backing plate to revolve about the spindle very slightly and bringing the anchor arm all the way to the main frame, rather than fixing it to the swing arm. This permits smoother braking on rough pitter-patter type surfaces. The front brake is downright puny looking; somewhat of a joke in appearance. However, it performed very well and we suspect that a larger unit on such a light machine would get the rider into the sort of trouble he could nicely do without.

The very generously finned engine performs smoothly with good power at low revs, and this is precisely what is needed in rough scrambles racing. A long, rather slender, expansion chamber helps to spread the power down low and the engine is not peaky anywhere throughout the range. It pulls steadily until the power peak, which is at an unusually low 5800 rpm. Very "over-square" borestroke dimensions make the Husky engine a truly shortstroke design. On this basis one could expect rather good engine component life using the power peak as maximum. Needle roller bearings are used in both the connecting rod small and big end while the crank assembly is mounted on double ball bearings at both ends.

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

With over nine inches of ground clearance the Husky is not in great danger of crashing its engine cases. We would like to see a "bash-plate" fitted for the western U.S. where the unexpected boulders can get rather large at times. This will undoubtedly be one of the first modifications for desert events. Well out of the way, and very inconspicuous, the side stand folds almost parallel to the swing arm. This is a nice feature; usually riders have to remove the stand, or a large rock does it for you, and then from then on there is a problem when it comes time to park the motorcycle.

All in all, we liked the Husky; as we said earlier it is a racer for the serious minded competitor and not for the weekend rider to go trials riding in the hills. The CYCLE WORLD test was carried out with the standard overlay rear sprocket in place and this does permit a useful low gear ratio that would lend itself to brisk trail riding. The Husqvarna factory claims 22 bhp at 5800 rpm; this is a very real and honest claim that, strangely enough, coincides with the horsepower figures in this month's Technicalities (page 14). The distributor has modified this figure to give us a "gross" horsepower of 31. He might be justified in doing so as the Husky fairly blew-off another scrambler that carries a very optimistic, near 30 bhp claim.

HUSQVARNA

250 MOTO-CROSS

$965