A NURBURGRING LAP

an invitation from Anke-Eve Goldmann

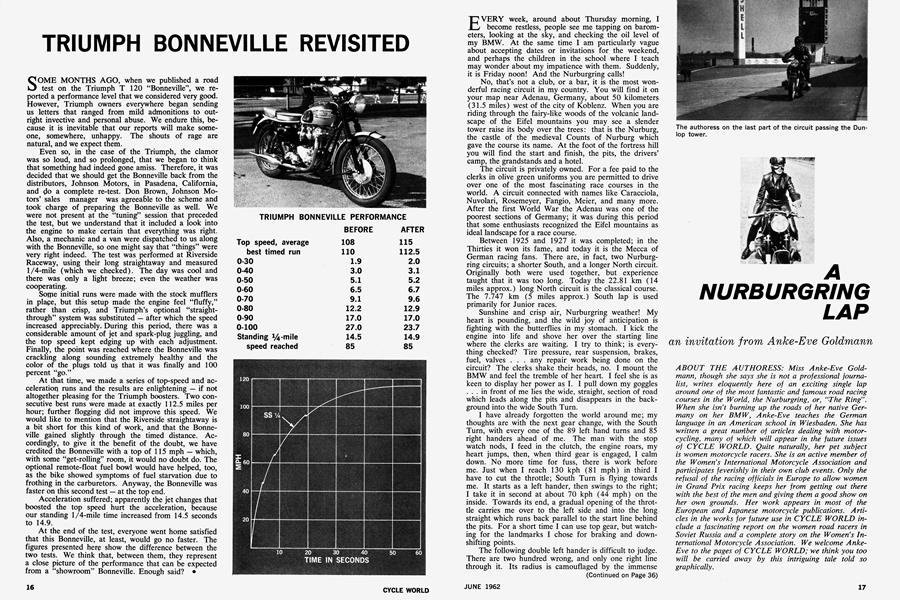

ABOUT THE AUTHORESS: Miss Anke-Eve Goldmann, though she says she is not a professional journalist, writes eloquently here of an exciting single lap around one of the most fantastic and famous road racing courses in the World, the Nurburgring, or, “The Ring”. When she isn’t burning up the roads of her native Germany on her BMW, Anke-Eve teaches the German language in an American school in Wiesbaden. She has written a great number of articles dealing with motorcycling, many of which will appear in the future issues of CYCLE WORLD. Quite naturally, her pet subject is women motorcycle racers. She is an active member of the Women’s International Motorcycle Association and participates feverishly in their own club events. Only the refusal of the racing officials in Europe to allow women in Grand Prix racing keeps her from getting out there with the best of the men and giving them a good show on her own grounds. Her work appears in most of the European and Japanese motorcycle publications. Articles in the works for future use in CYCLE WORLD include a fascinating report on the women road racers in Soviet Russia and a complete story on the Women’s International Motorcycle Association. We welcome AnkeEve to the pages of CYCLE WORLD; we think you too will be carried away by this intriguing tale told so graphically.

EVERY week, around about Thursday morning, I become restless, people see me tapping on barometers, looking at the sky, and checking the oil level of my BMW. At the same time I am particularly vague about accepting dates or invitations for the weekend, and perhaps the children in the school where I teach may wonder about my impatience with them. Suddenly, it is Friday noon! And the Nurburgring calls!

No, that’s not a club, or a bar, it is the most wonderful racing circuit in my country. You will find it on your map near Adenau, Germany, about 50 kilometers (31.5 miles) west of the city of Koblenz. When you are riding through the fairy-like woods of the volcanic landscape of the Eifel mountains you may see a slender tower raise its body over the trees: that is the Nurburg, the castle of the medieval Counts of Nurburg which gave the course its name. At the foot of the fortress hill you will find the start and finish, the pits, the drivers’ camp, the grandstands and a hotel.

The circuit is privately owned. For a fee paid to the clerks in olive green uniforms you are permitted to drive over one of the most fascinating race courses in the world. A circuit connected with names like Caracciola, Nuvolari, Rosemeyer, Fangio, Meier, and many more. After the first World War the Adenau was one of the poorest sections of Germany; it was during this period that some enthusiasts recognized the Eifel mountains as ideal landscape for a race course.

Between 1925 and 1927 it was completed; in the Thirties it won its fame, and today it is the Mecca of German racing fans. There are, in fact, two Nurburgring circuits; a shorter South, and a longer North circuit. Originally both were used together, but experience taught that it was too long. Today the 22.81 km (14 miles approx.) long North circuit is the classical course. The 7.747 km (5 miles approx.) South lap is used primarily for Junior races.

Sunshine and crisp air, Nurburgring weather! My heart is pounding, and the wild joy of anticipation is fighting with the butterflies in my stomach. I kick the engine into life and shove her over the starting line where the clerks are waiting. I try to think; is everything checked? Tire pressure, rear suspension, brakes, fuel, valves . . . any repair work being done on the circuit? The clerks shake their heads, no. I mount the BMW and feel the tremble of her heart. I feel she is as keen to display her power as I. I pull down my goggles ... in front of me lies the wide, straight, section of road which leads along the pits and disappears in the background into the wide South Turn.

I have already forgotten the world around me; my thoughts are with the next gear change, with the South Turn, with every one of the 89 left hand turns and 85 right handers ahead of me. The man with the stop watch nods, I feed in the clutch, the engine roars, my heart jumps, then, when third gear is engaged, I calm down. No more time for fuss, there is work before me. Just when I reach 130 kph (81 mph) in third I have to cut the throttle; South Turn is flying towards me. It starts as a left hander, then swings to the right; I take it in second at about 70 kph (44 mph) on the inside. Towards its end, a gradual opening of the throttle carries me over to the left side and into the long straight which runs back parallel to the start line behind the pits. For a short time I can use top gear, but watching for the landmarks I chose for braking and downshifting points.

The following double left hander is difficult to judge. There are two hundred wrong, and only one right line through it. Its radius is camouflaged by the immense width of the road at this point, and it is interrupted by a short straight with two bumps in it. I still have a great deal to learn there.

(Continued on Page 36)

The track now falls into a cadence of quick right-left swervery, descending through the woods: Hatzenback, here

everything depends upon lightning braking, accelerating, and knowing whether second or third gear is better. Shortly after the 3 km mark I catapult the BMW out of the woods through a descending left into a ditch where my ribs are pressed rudely onto the tank. A short ascent, and then you fly up from the seat, and the bike heaves herself off its suspension. This spot is called Hocheichen.

Down again, and up and to the right. If you know the course you can accelerate brusquely in third, though vision is barred around Quiddelbacher Hohe. A full throttle left follows: in top gear the BMW now reaches 160 kph (99 mph), but the road is bumpy and if your model doesn’t steer like a rock you had better take care here. At Schwedenkreuz I have to step on my brakes with everything the tires will stand for, and sit up for air braking. Down to third, then second; there is Aremberg, a tricky right turn. Flat at the outside, banked inwards at the right, you can take it faster on the inside. Aremberg can be taken at 70 kph (44 mph), but I do not dare try. After Aremberg a narrow, slightly swerving road descends into the deep hole of Fuchsrohre.

Some men riders attain 160 kph (99 mph) here, and more; for them it’s the fastest part of the “Ring”. But not for me, I am no man, and I lack the courage to rocket down into that dark ravine. At the deepest point the bike has to be banked over to the left, right down to the rocker box, to avoid the right side of the road, which, taking to the left, ascends steeply out of Fuchsrohre. The bottom of that lousy piece of road is halfway between the 6 km mark and the 7 km mark. Down there where there is no vision of how the road continues, I risk a timid 120 kph (75 mph), which is sufficient to bounce me down on the tank.

Up the bike shoots, and I am not yet liberated from the force of gravity acting upon my body when the double “S” bend of Adenauer Forst first calls for the utmost attention. The road falls suddenly from the ascending to the level in the middle of a left hander. When you shoot up out of the beastly hole of Fuchsrohre it seems the road ends in the sky. I am still no friend to that part of the course and constantly hit the wrong line.

When you lose time at Adenauer Forst you will fail to attain the 130 kph (81 mph) possible before a soft left leads to the Kallenhard, a narrow right hander which opens into a series of right and left handers in a steep descent. If you are a good rider you can take these combination turns pi third most of the time, but you have to know-*your brakes here.

Now, I am at Breidscheid, the deepest point on the “Ring”. Altitude 320 meters (1,050 feet). The road jumps over a bridge, falls down into a deep ditch. Again I ache under the whip of gravity while trying to swirl the BMW from the left to the right side because immediately after Breidscheid the road remounts in a steep right turn. It demands more boldness than I am possessed with. I let the BMW yowl in second, pass Ex-Muhle, and prepare for Bergwerk, a right turn with vision blocked by a steep rock. If you know it, you can take it with much more steam than it seems the situation could stand at first glance.

After this point the descent to Hohe Acht begins. I let loose all the horses of the engine through the ascending, wide sweeping bends. The engine revs to about 7000 rpm in third gear. Here a powerful engine wins valuable seconds. The “S” bend between Kesselchen and the 13 km mark can be taken with the throttle almost wide open, though it looks quite frightening from “downstairs”. But there is no need of braking here. A wide left hander leading to the Karrussell is taken in second gear with the engine singing. A short ascent, third gear for a second or two, back into second gear, and there’s the Karrussell, perhaps the most spectacular point of the “Ring”.

The Karrussell is a 200 degree left, very narrow. The outer part of the road is horizontal; you would brake down to 40 kph (25 mph) there. But the inside of the curve, perhaps 10 feet wide, is banked into about 45 degrees. Take a deep breath, and let your bike drop into that circus in second gear at about 60 kph (37 mph), lying almost horizontally! But woe to those who get over the edge of the banking! They are thrown out into the hedges like an atom from a cyclotron!

Forty-five feet before the end of the Karrussell you can open the throttle abruptly, and the horsepower shoots you out of the banking back on to the horizontal road. A steep left hander leads to the highest point of the “Ring”, Hohe Acht, 620 meters (3,850 feet) above sea level. Within 5 kms you have climbed 300 meters (1,863 feet). My knees are still slightly shaky from the centrifugal force of the Karrussell when I pass the twistiness of Wippermann, famous for its bumps. Then a wide left sweeper descends steeply to Esbach.

Next there is a short piece of level road that the BMW really flies over. Keep the tightest grip with the knees here. Immediately afterwards I crash down into the suspension at the bottom of the deep hole of Brunnchen. Everything experienced in Fuchrohre seems child’s play by comparison here, it presses all the air out of my lungs. But, I have to watch the road which ascends steeply in a right hander. Just at the point where the bend ends the road becomes horizontal again, and abruptly at that! Don’t try to steer at that moment when your mount comes roaring out of Brunnchen and loses almost every bit of wheel grip.

You now have about 300 feet of time to readjust your strained stomach and brains, that is if you get no shock from the strong sun’s rays in the afternoon. At that point you are riding exactly into the sun, coming out of deep shadow. Through the wide bends of Pflanzgarten you can steady up again, at least a little. Good riders attain 140 kph (88 mph) through this swervy section.

(Continued on Page 38)

Immediately before Schwalbenschwanz when you are banked over sharply to the right you pass over a very bumpy bridge. This can give you goosepimples all over. More than once I have been in a mess here.

Then, I brake down for Schwalbenschwanz, a somewhat less frightening repetition of the Karrussell, but to the left this time. It demands second gear; still in the banking I engage third and yank the BMW out onto the flat road. Another right hander and back into the woods again. I watch ahead and to the right, until I get the first glimpse of sunny patches of green between the trees, then I open her up full and roar out of the woods. Now through a wide right hander, into the long straight. I accelerate hard, take top gear and settle down on the tank.

If carburetion is all right, I attain top speed here. I aim for the bridge at the 22 km mark, and exactly under it the road edges to the left. I aim at one of the letters of a sign on the bridge, because, if I wish to take that turn at full throttle I have to take the BMW from the extreme right side, through the bridge, under that letter, well banked over to the left, without seeing where I am going. After the bridge the road ascends, and speeds fall to about 130 kph (81 mph) because of an easy right which is followed by the final ascent to the finish line. When I get sight of the timekeeper’s stand I cut the throttle, sit up, shift down, brake, and stop.

It is a queer feeling to feel the ground under my feet again; the angry roar of the engine has turned to a peaceful burbling again. The wild chorus of thousands of wind goblins is still in my ears, and my body feels awkward now that the wind pressure has abated. There I am, back on earth, returning from one of the most enchanting, fascinating, breathtaking experiences I know of. In a few minutes I shall repeat it, and I know it will have lost none of its wild charm.

Whenever you visit the “Ring”, don’t try to force it. Ride 20 laps without ambitions, and then 20 more experimenting with gears and lines. Only after that, “try”. If you reverse that order, you will pay for it. It is better to come on weekdays, then you have the “Ring” almost entirely to yourself. If you cannot avoid weekends take a Saturday over a Sunday and the hours before 10 AM over the others of the day. The “Ring” is open to every visitor because the Nurburgring Company has to rely upon the money these people pay. Beware! Most of these visitors are inexperienced car drivers, some of whom are stupid enough to drive the “Ring” in the wrong direction.

Even busses and cars with coffee visitors circle the track; try to avoid them. And, do not forget to walk through the lovely woods and climb the Nurburg. It is a fairy land. When you return home you will understand why, for us, it is just “THE RING”. •