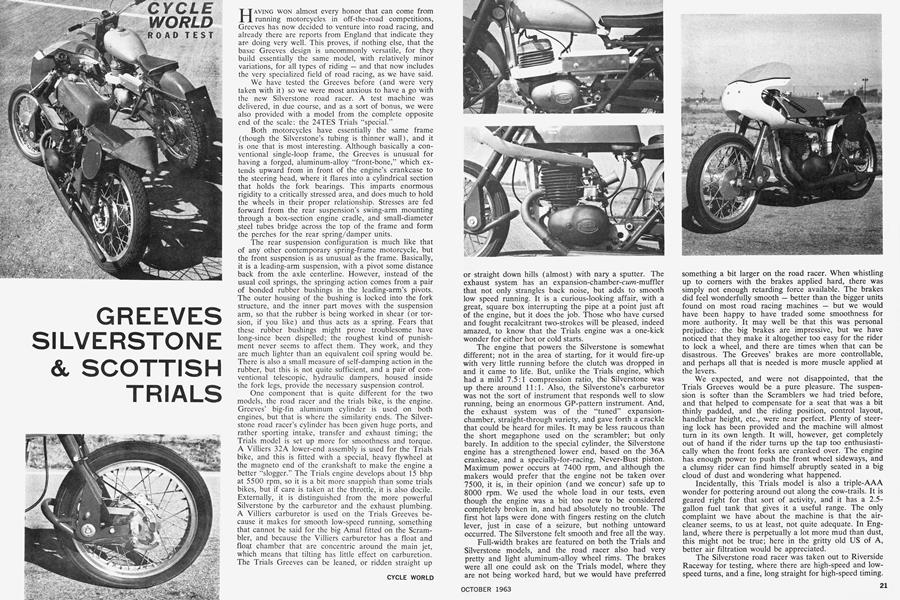

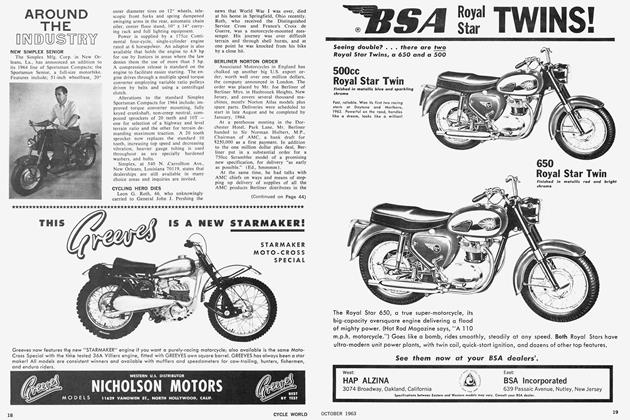

GREEVES SILVERSTONE & SCOTTISH TRIALS

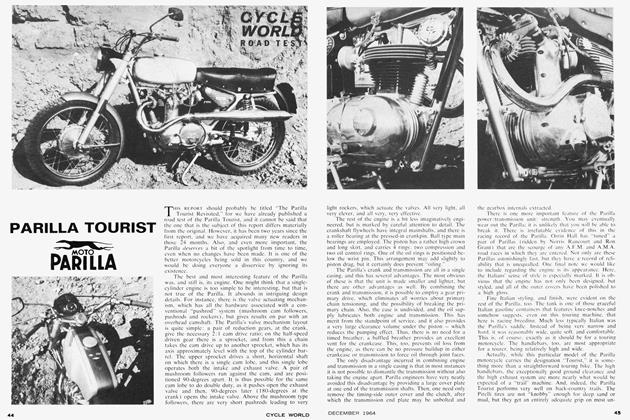

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

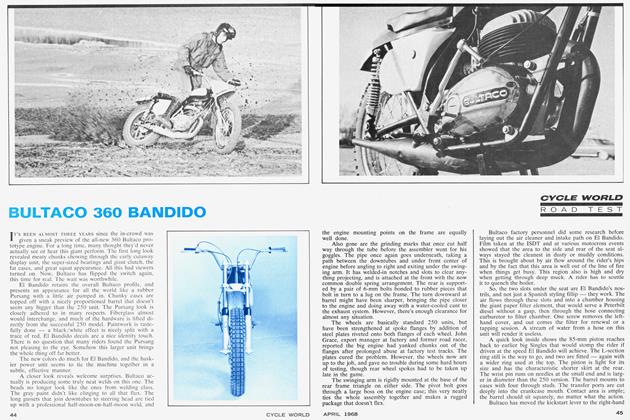

HAVING WON almost every honor that can come from running motorcycles in off-the-road competitions, Greeves has now decided to venture into road racing, and already there are reports from England that indicate they are doing very well. This proves, if nothing else, that the basic Greeves design is uncommonly versatile, for they build essentially the same model, with relatively minor variations, for all types of riding — and that now includes the very specialized field of road racing, as we have said.

We have tested the Greeves before (and were very taken with it) so we were most anxious to have a go with the new Silverstone road racer. A test machine was delivered, in due course, and as a sort of bonus, we were also provided with a model from the complete opposite end of the scale: the 24TES Trials “special.”

Both motorcycles have essentially the same frame (though the Silverstone’s tubing is thinner wall), and it is one that is most interesting. Although basically a conventional single-loop frame, the Greeves is unusual for having a forged, aluminum-alloy “front-bone,” which extends upward from in front of the engine’s crankcase to the steering head, where it flares into a cylindrical section that holds the fork bearings. This imparts enormous rigidity to a critically stressed area, and does much to hold the wheels in their proper relationship. Stresses are fed forward from the rear suspension’s swing-arm mounting through a box-section engine cradle, and small-diameter ,steel tubes bridge across the top of the frame and form the perches for the rear spring/damper units.

The rear suspension configuration is much like that of any other contemporary spring-frame motorcycle, but the front suspension is as unusual as the frame. Basically, it is a leading-arm suspension, with a pivot some distance back from the axle centerline. However, instead of the usual coil springs, the springing action comes from a pair of bonded rubber bushings in the leading-arm’s pivots. The outer housing of the bushing is locked into the fork structure, and the inner part moves with the suspension arm, so that the rubber is being worked in shear (or torsion, if you like) and thus acts as a spring. Fears that these rubber bushings might prove troublesome have long-since been dispelled; the roughest kind of punishment never seems to affect them. They work, and they are much lighter than an equivalent coil spring would be. There is also a small measure of self-damping action in the rubber, but this is not quite sufficient, and a pair of conventional telescopic, hydraulic dampers, housed inside the fork legs, provide the necessary suspension control.

One component that is quite different for the two models, the road racer and the trials bike, is the engine. Greeves’ big-fin aluminum cylinder is used on both engines, but that is where the similarity ends. The Silverstone road racer’s cylinder has been given huge ports, and rather sporting intake, transfer and exhaust timing; the Trials model is set up more for smoothness and torque. A Villiers 32A lower-end assembly is used for the Trials bike, and this is fitted with a special, heavy flywheel at the magneto end of the crankshaft to make the engine a better “slogger.” The Trials engine develops about 15 bhp at 5500 rpm, so it is a bit more snappish than some trials bikes, but if care is taken at the throttle, it is also docile. Externally, it is distinguished from the more powerful Silverstone by the carburetor and the exhaust plumbing. A Villiers carburetor is used on the Trials Greeves because it makes for smooth low-speed running, something that cannot be said for the big Amal fitted on the Scrambler, and because the Villiers carburetor has a float and floa,t chamber that are concentric around the main jet, which means that tilting has little effect on carburetion. The Trials Greeves can be leaned, or ridden straight up or straight down hills (almost) with nary a sputter. The exhaust system has an expansion-chamber-cwra-muffler that not only strangles back noise, but adds to smooth low speed running. It is a curious-looking affair, with a great, square box interrupting the pipe at a point just aft of the engine, but it does the job. Those who have cursed and fought recalcitrant two-strokes will be pleased, indeed amazed, to know that the Trials engine was a one-kick wonder for either hot or cold starts.

The engine that powers the Silverstone is somewhat different; not in the area of starting, for it would fire-up with very little running before the clutch was dropped in and it came to life. But, unlike the Trials engine, which had a mild 7.5:1 compression ratio, the Silverstone was up there around 11:1. Also, the Silverstone’s carburetor was not the sort of instrument that responds well to slow running, being an enormous GP-pattern instrument. And, the exhaust system was of the “tuned” expansionchamber, straight-through variety, and gave forth a crackle that could be heard for miles. It may be less raucous than the short megaphone used on the scrambler; but only barely. In addition to the special cylinder, the Silverstone engine has a strengthened lower end, based on the 36A crankcase, and a specially-for-racing, Never-Bust piston. Maximum power occurs at 7400 rpm, and although the makers would prefer that the engine not be taken over 7500, it is, in their opinion (and we concur) safe up to 8000 rpm. We used the whole load in our tests, even though the engine was a bit too new to be considered completely broken in, and had absolutely no trouble. The first hot laps were done with fingers resting on the clutch lever, just in case of a seizure, but nothing untoward occurred. The Silverstone felt smooth and free all the way.

Full-width brakes are featured on both the Trials and Silverstone models, and the road racer also had very pretty and light aluminum-alloy wheel rims. The brakes were all one could ask on the Trials model, where they are not being worked hard, but we would have preferred

something a bit larger on the road racer. When whistling up to comers with the brakes applied hard, there was simply not enough retarding force available. The brakes did feel wonderfully smooth — better than the bigger units found on most road racing machines — but we would have been happy to have traded some smoothness for more authority. It may well be that this was personal prejudice: the big brakes are impressive, but we have noticed that they make it altogether too easy for the rider to lock a wheel, and there are times when that can be disastrous. The Greeves’ brakes are more controllable, and perhaps all that is needed is more muscle applied at the levers.

We expected, and were not disappointed, that the Trials Greeves would be a pure pleasure. The suspension is softer than the Scramblers we had tried before, and that helped to compensate for a seat that was a bit thinly padded, and the riding position, control layout, handlebar height, etc., were near perfect. Plenty of steering lock has been provided and the machine will almost turn in its own length. It will, however, get completely out of hand if the rider turns up the tap too enthusiastically when the front forks are cranked over. The engine has enough power to push the front wheel sideways, and a clumsy rider can find himself abruptly seated in a big cloud of dust and wondering what happened.

Incidentally, this Trials model is also a triple-AAA wonder for pottering around out along the cow-trails. It is geared right for that sort of activity, and it has a 2.5gallon fuel tank that gives it a useful range. The only complaint we have about the machine is that the aircleaner seems, to us at least, not quite adequate. In England, where there is perpetually a lot more mud than dust, this might not be true; here in the gritty old US of A, better air filtration would be appreciated.

The Silverstone road racer was taken out to Riverside Raceway for testing, where there are high-speed and lowspeed turns, and a fine, long straight for high-speed timing. With the gearing we had installed, the bike’s top speed was limited by the permitted engine speed to just a hair under 106 mph, which isn’t bad for a 15-incher, as you will admit. The Silverstone has a fairing, but it is a trifle abbreviated, and not as slippery as the ones used on most other bikes. However, the Silverstone is intended as a short-course machine, and not only the fairing, but the gearing and engine output characteristics are directed toward that end. Close-ratio gears are fitted, but their staging is not all that far removed from what one would expect in a sports/touring bike. This is done partly to give the bike a lot of steam out of slow corners and from the starting line, and partly because the engine has such a good spread of power that closer ratios are not necessary. That strong feeling begins at about 4500-5000 rpm, and it remains, getting stronger all the way, until the engine nears the 8000-rpm limit, where the power drops away sharply enough to remind the rider it is time to shift — even if he isn’t watching the tachometer.

There can be little doubt that some power has been sacrificed to get broad-range torque, but we rather liked this setup. The Silverstone does not require that its rider work nearly so hard at stirring the gear lever as is usually the case, and it makes the bike more controllable to have the power right there on tap when it is needed. We have ridden road-racing machines that “came-in” so suddenly that at times they tried to hurl themselves straight off the corner. Absolute peak power is not everything.

Our minds are still not settled in the matter of the Silverstone’s handling. The first couple of laps were something we would like to forget, as we found to our sorrow that the well-known Greeves front-fork wag takes a new and exceedingly interesting form in the Silverstone. No one dropped the bike, but it gave us some moments before we became accustomed to its peculiarities. Let us state, right off, that the Silverstone will carve through a fast bend with the best of them; it just takes a little more effort, and courage, on the part of the rider. When the rider gets it into a fast (85-95 mph) bend, he will find that the fork-wag, which is always present in the scrambler but missing on the Silverstone when it is travelling straight, comes back.

In all fairness, we must say that we learned to live with all of the monkey-motion that appeared when the Silverstone was well heeled over and going strong. The trick, and it is not quite so easy as the telling, is to relax and let the confounded thing squiggle. The Silverstone will tend to drift outward a bit more than is usual, so it is necessary to aim it in a bit tighter on the approach, but with practice it can be made to corner as fast as any of its contemporaries. Actually, the slow turns cause more of a problem. Our test bike, an early example, had no steering damper (a damper is now available) and when we had it all leaned down working around a slow turn, those funny front-fork motions were especially bothersome; although, again, nothing that the rider cannot learn to live with.

There was one very odd thing learned in connection with the Greeves: it responds particularly well to the contemporary British technique of poking down one’s knee on the side of the turn. None of us had tried this very much — most bikes feel just fine with the rider tucked-in tightly — but one of our number discovered, quite by accident, that the Silverstone would behave much better if the rider stuck out his knee. The Compleate Silverstone Technique, for anyone who is interested, is to “ride-loose”, applying as little muscle at the bars as possible, and doing everything (except braking) in a smooth, even languid, fashion — and poking out the appropriate knee. •

GREEVES

24RAS Silverstone

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE