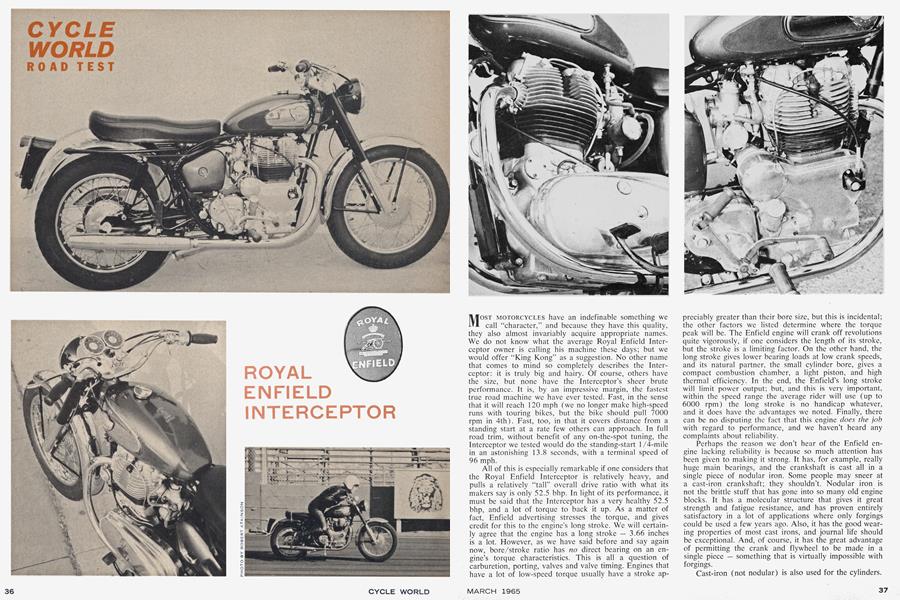

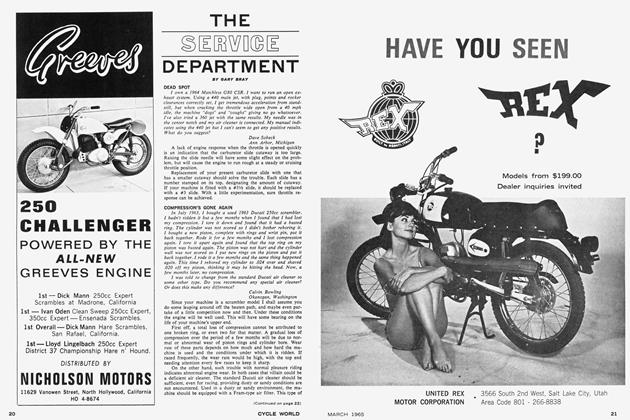

ROYAL ENFIELD INTERCEPTOR

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

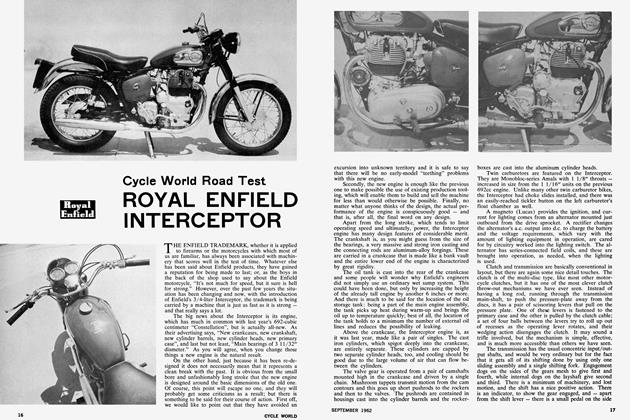

MOST MOTORCYCLES have an indefinable something we call "character," and because they have this quality, they also almost invariably acquire appropriate names. We do not know what the average Royal Enfield Interceptor owner is calling his machine these days; but we would offer "King Kong" as a suggestion. No other name that comes to mind so completely describes the Interceptor: it is truly big and hairy. Of course, others have the size, but none have the Interceptor's sheer brute performance. It is, by an impressive margin, the fastest true road machine we have ever tested. Fast, in the sense that it will reach 120 mph (we no longer make high-speed runs with touring bikes, but the bike should pull 7000 rpm in 4th). Fast, too, in that it covers distance from a standing start at a rate few others can approach. In full road trim, without benefit of any on-the-spot tuning, the Interceptor we tested would do the standing-start 1/4-mile in an astonishing 13.8 seconds, with a terminal speed of 96 mph.

All of this is especially remarkable if one considers that the Royal Enfield Interceptor is relatively heavy, and pulls a relatively "tall" overall drive ratio with what its makers say is only 52.5 bhp. In light of its performance, it must be said that the Interceptor has a very healthy 52.5 bhp, and a lot of torque to back it up. As a matter of fact, Enfield advertising stresses the torque, and gives credit for this to the engine's long stroke. We will certainly agree that the engine has a long stroke — 3.66 inches is a lot. However, as we have said before and say again now, bore/stroke ratio has no direct bearing on an engine's torque characteristics. This is all a question of carburetion, porting, valves and valve timing. Engines that have a lot of low-speed torque usually have a stroke ap-

preciably greater than their bore size, but this is incidental; the other factors we listed determine where the torque peak will be. The Enfield engine will crank off revolutions quite vigorously, if one considers the length of its stroke, but the stroke is a limiting factor. On the other hand, the long stroke gives lower bearing loads at low crank speeds, and its natural partner, the small cylinder bore, gives a compact combustion chamber, a light piston, and high thermal efficiency. In the end, the Enfield's long stroke will limit power output; but, and this is very important, within the speed range the average rider wiíl use (up to 6000 rpm) the long stroke is no handicap whatever, and it does have the advantages we noted. Finally, there can be no disputing the fact that this engine does the job with regard to performance, and we haven't heard any complaints about reliability.

Perhaps the reason we don't hear of the Enfield engine lacking reliability is because so much attention has been given to making it strong. It has, for example, really huge main bearings, and the crankshaft is cast all in a single piece of nodular iron. Some people may sneer at a cast-iron crankshaft; they shouldn't. Nodular iron is not the brittle stuff that has gone into so many old engine blocks. It has a molecular structure that gives it great strength and fatigue resistance, and has proven entirely satisfactory in a lot of applications where only forgings could be used a few years ago. Also, it has the good wearing properties of most cast irons, and journal life should be exceptional. And, of course, it has the great advantage of permitting the crank and flywheel to be made in a single piece — something that is virtually impossible with forgings.

Cast-iron (not nodular) is also used for the cylinders. These are, by the way, separate castings, just as each cylinder head is cast individually (but of aluminum; not iron). This type construction adds a few bits and pieces to the assembly total, but there are times when it makes repairs easier, and less expensive, and it may be that improved cooling is also obtained.

Another of the Enfield engine's several unusual features is that while dry-sump lubrication is employed, the oil tank is cast in as an integral part of the crankcase. This may appear to be a slightly peculiar arrangement, but it helps keep down the height of an inherently tall engine, and as the oil is actually contained in the engine proper, warm-up is more rapid. Quick warming of the oil is particularly important if the bike is subjected to short-haul operation, as acid engine vapors tend to condense and collect in oil when oil does not have an opportunity to come up to temperature. And, too, in very cold climates, oil carried in a remote tank will tend to be a bit cool for best operation. While on the subject of the lubricating system, we should make mention of the fact that the Enfield engine has an oil filter — an item that is both important, and unfortunately rare, in motorcycle engines. Almost as important as the filter itself is the fact that the housing into which the felt filter element is fitted is located right on the side of the crankcase, where it is easily reached and the owner will be more likely to clean and replace it at the specified intervals.

The Enfield's transmission does not follow the modern trend of being "in-unit" with the engine, but the arrangement used is in many respects superior. One of the big advantages of unit construction is that with engine and transmission tied rigidly together, all problems of primary chain-pull are eliminated. The Enfield gets the same advantage by having a separate transmission bolted solidly to the back of the crankcase. And, this makes it possible to remove, replace and/or repair the transmission without dismantling the engine. This layout has special value in the Enfield because the engine/transmission package is used as a part of the frame. The tubes at the back of the frame that carry the suspension units and the swing arm pivots are bolted securely to the transmission. Thus, considerable stiffness is imparted to the frame just where it is needed, and chain-pull between the countershaft sprocket and rear wheel are fed directly, through the swing arm and its mounts, to the transmission casing. In all, this layout would be hard to improve upon.

We liked the brakes on this new Royal Enfield Interceptor better than those on the previous bike we tested. Where before the brakes shuddered and squeaked, those on the new Interceptor did an adequate, if slightly leisurely job of stopping the machine and rider. Perhaps the earlier example was just a lemon in this department; and perhaps Enfield have made changes in brake linings, or something. Incidentally, while there are full-width aluminum hubs front and rear, the rear hub contains only bearings and the rubber-cushioned drive device. The brake, coyly masked by the drive sprocket, is an ordinary, unpretentious cast-iron affair. The front brake is, however, actually inside the lovely finned aluminum hub and has all the advantages that accrue to devices of the type.

Good handling and good ride are features of the Interceptor. If you bank it over toQ vigorously there are assorted bits of hardware that begin to scuff themselves away on the paving but the bike remains rock-steady even when there is a lot of graunching in process underneath. As a matter of fact, under any and all conditions it is stability that characterizes the Interceptor's handling. Nothing seems to upset its equilibrium very much — which is a very good thing in a machine so ghastly fast.

Speaking of speed, we would like to comment that the Interceptor's handlebars are too high and wide for the speeds of which it is so abundantly capable. The bike will go like the wind, and with the bars it has, the wind tries to pluck the rider right from the saddle. Anyone who likes to cruise at brisker-than-average speeds, and who does not like windshields, would be well advised to outfit the bike with low, flat bars that will allow him to lean into the wind. Otherwise, the need for clinging tightly to the motorcycle reduces the joy of fast touring considerably.

There is a lot of enjoyment to be had touring on the Interceptor. It has bags of power, and you have only to turn on the tap and all others fall rapidly behind. The bike steams up mountain grades like they do not even exist, and its handling and performance give it a cut-andthrust capability in traffic that is unmatched by anything else. •

ROYAL ENFIELD

INTERCEPTOR

$1,247.00