(TECHNICALITIES)

GORDON H. JENNINGS

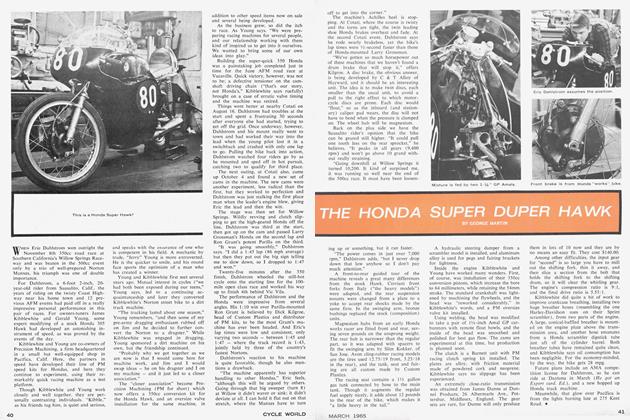

IN THIS COLUMN, two months ago, I promised additional details about the modifications made to the Honda engine in my Cotton Telstar road racing bike. As it happens, we (my good friend, associate and "tuner," Brian Crawford, and myself) have more development work to do than was envisioned at the end of the 1964 racing season. The limit of power to be had from the CB-77 engine is not yet in sight, but we have begun to have reliability problems and these must be corrected before much thought is given to added horsepower.

Racing experience (our own and that of others) has already done a lot for the re liability of modified CB-77 engines. For example, at one time there was a fairly high frequency of piston scuffing, and a few outright failures, with the ForgedTrue/ Webco 350cc kit. In addition, there were cases (mostly in racing) where inadequate lubrication caused wrist-pins to seize in the pistons. To counter these things, oilfeed holes are now provided in the wristpin bosses, and oil-retaining grooves are. cut in the piston skirts. Positive lubrication of the piston skirt is insured by oil fed directly to the skirt from a hole in the cylinder liner. This oil comes through a drilled passage from the oil gallery that runs along the front of the cylinder block. With these improvements in lubrication, the CB-77 engine becomes remarkably re liable, even when taking the additional pressure that comes with the 350 kit.

Unfortunately, if you are going for a really all-out racing engine, the modifica tions do not end with the installation of a 350 kit. We have milled out the cylinder head's intake ports and welded in stubs to give a straighter path into the intake valve, and to suit the porting to a pair of 29mm (Ll4") Dellorto carburetors. A 29mm carburetor throat probably seems some what too big for a 175cc cylinder, but we get excellent carburetion over a wide en gine speed range, and there are indications that we could use even larger carburetors - probably about 32mm. Larger intake valves were to be the next move: we had not done this before because to get a worthwhile increase in intake valve size it is necessary to change the stem angle and location. Sooner or later, that will come; for the moment we are occupied with more pressing business.

One of the changes made was to elimi nate the CB-77's head gasket. The reason for this was two-fold: first, by simply re moving the head gasket we could get a 13: 1 compression ratio with 12: 1 (the highest available) pistons; second, it is my feeling that head gaskets should be elimi nated wherever possible. The head gasket that does not exist cannot blow out. In the case of the Honda engine, we were able to make a very effective seal by lapping the tops of the cylinders and the underside of the cylinder head. This was done using grinding paste (coarse and then fine) and a flat glass plate. However, even though this gives an absolutely leak-free fire joint, the fact that the cylinder liners stand "proud" above the block a few thou' creates an oil seal problem. The oil passages that come up from the block to the head have a hollow dowel and a rubber sealing ring at the head face. In the standard layout, a. hole in the head gasket fits around the sealing ring and prevents it from being squeezed absolutely flat. To make a bit of clearance for the sealing ring, we simply cut a small 45-degree chamfer around the oil-feed dowel holes where they join at the block and the head faces. Another seal is necessary around the timing-chain chest, and we use a small, very thin gasket here.

(Continued on page 14)

The big problem we have encountered, and have not solved at this writing, is wristpin failure. The Honda connecting rod's small end is not bushed; the wrist pin runs directly against the steel rod eye. There is a thin copper flash on the rod, but it is likely that the coating is there simply to make possible the surface hardening of only the rod's big end. The copper will prevent a chemical hardening bath from reaching the steel, and it is common practice to copper coat all but bearing surfaces on parts like connecting rods. The surface-hardening treatment is needed to make a surface inside the rod big-end suitable as an outer race for the roller bearings, but such a surface is brittle as well as hard. Should the rod be hardened all over, it would be extremely likely to break, as the working of the core metal would start cracks in the hardened surface. Therefore, manufacturers limit the hardened area by copper plating all but the surfaces where hardness is required. That is, I am sure, the reason for the thin coating of copper seen on Honda rods. Of course, it is possible that the copper flash might give some benefits as a bearing surface, but it is far too thin to have a marked effect. For the most part, you may consider that there is a steel-against-steel situation at the eye of the connecting rod.

The lack of a bearing-bush at the rod eye has no noticeable effect on the service life of a stock CB-77. Nor, indeed, is there any sign of a problem with just a 350 kit. The difficulty arises only when the tuner goes to more extensive hop-up work. Then, thermal and mechanical loads combine to cause a wristpin failure. Quite frankly, we are not entirely sure where the failure begins; when the engine is stripped down we find the pins welded to the rod eyes, and galling badly inside the pistons. It may be that the first failure occurs at the rod eye, and then the galling is caused in the piston. Or, equally possible, it may be that heat and pressure are distorting the piston and locking the pins, after which all of the rod swing motion is taken at the rod eye and only then does the pin weld itself to the rod.

On the theory that it is a combination of both these effects, we are going to give the pin slightly more clearance inside the piston, and then tin-plate the rod eye. We will first ream the eye of the rod slightly oversize, then plate enough to close it back slightly undersize, and finally finish-ream to the original diameter. With any luck at all, this measure will correct the difficulty. In any case, unless we can improve wristpin life (which is only perhaps 100 racing miles now) there will be no point in reaching for more power.

Assuming that we are able to regain some measure of reliability, the next step will be to produce a new cylinder head, with bigger valves and ports and to which yet bigger carburetors can be fitted. Also, we want to try slightly different exhaust pipe diameters and different megaphones. With these changes, we will be continuing experiments with valve timing. Almost from the beginning of this project, I have been working with Harman and Collins, and our Honda engine has been a sort of test bed for H&C camshafts. Up to this point, we have been using "grinds" essentially identical to those available from dealers, but we have been experimenting with metals in the cams and followers. Follower wear has been something of a problem, with the loads imposed by high valve-lift rates, racing valve springs, and sustained high-speed operation. We think that we have found the answer to this problem, but will not make any ringing declarations until we are certain. There are some radical experimental "grinds" we would like to try, too, but we think it is a mistake to proceed in a project like this with more than one step at a time.

Having really only scratched the surface in this Honda hop-up project, we are long on problems and short on answers, but we expect that the situation will change. Many of the difficulties could be over come by making a lot of special parts, but we are trying to restrict ourselves to mea sures the average amateur road racer would have within grasp. We can offer one very concrete bit of information about the CB-77 now, however: it will not be at all reliable with 13: 1 compression. This ap pears to be just over on the wrong side of the borderline. The engine will not ac tually fail immediately, but the pistons as sume a very unhealthy looking straw color and there is evidence of detonation. We ran our engine about 100 racing miles with 13:1 compression, and it lasted, but dam age from the thermal overload was such that new pistons and sleeves were required.

(Continued on page 16)

There is an interesting (I think) side to this road racing effort of mine. When one goes racing, one needs suitable leath ers, and in road racing "suitable" means the European-style one-piece racing leath ers. Obviously, one cannot buy these at the local men's wear store, and in point of fact there has been no supplier of such leathers in this country. Such one-piece suits as have been available are more like leather coveralls than the tight-fitting "sec ond skin" one needs for road racing. The only source of proper road racing leathers was England, and that meant ordering a very expensive item, sight unseen, and waiting interminably unless one wanted to pay the premium for air travel.

Now, you active and would-be road racers might be pleased to know, there are more convenient means of getting road racing leathers. They can be made to order here in America, or brought in (via a reputable, direct line) from England. Our esteemed Fearless Leader, Himself Park hurst, ordered his leathers from D. Lewis, Ltd., when that English firm brought itself to our attention by buying some advertis ing space in CYCLE WORLD. We wondered how it would work out to order from England, using only a catalogue. The an swer is that it works fine. D. Lewis sends a supplementary list with each catalogue, giving prices in dollars for all items. The prices include postage, but only for surface mail; airmail service would require some other arrangement. However, the goods will arrive in due course, and from what we have seen, much of it is quite good - not all of the catalogued items will appeal much to American tastes. Cer tainly, Fearless Leader's leathers were very good indeed. They fit, and were made of first-rate hide. The price of these "ready made" leathers is $73.50, but the really serious racer might want to order the cus tom-made, skin-tight (no lining and no padding) suit. For this one you will need a special order form, to tell their cutters the distance from your knee-bone to your ankle-bone, etc. and you will also need $87.50.

(Continued on page 18)

The other alternative is one I chose. Needing the leathers in rather a hurry, I hustled off to Cal-Leathers Company and asked if they would be interested in mak ing an English-style suit to order. They would and they did. Some trimming and fitting was needed, because none of their existing patterns were made to fit someone riding with knees higher than elbows. Eventually however, it was found where the additions and subtractions had to be made, and I had a very satisfactory set of leathers. Cal-Leathers, and Webco (who distribute their products) became inter ested in road racing while all this was occurring, and they decided that they would add road racing one-piece suits to their regular line. As a result, these suits can now be obtained from Cal-Leathers by placing an order with Webco. The CalLeathers suit is made of good, tough horse-hide, and padded at the seat, hips, elbows and knees. It is fully lined, in nylon, and zips at the cuffs and ankles with a snap at the neck band. I asked that my suit be made without pockets, but I suppose they would be willing to add these if you want them. Webco will sell these racing suits for $84.95, made to order. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue