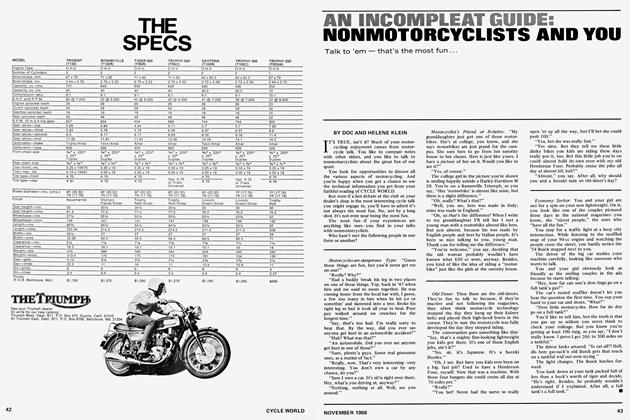

SEARS SR 250

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Last of the Split Singles

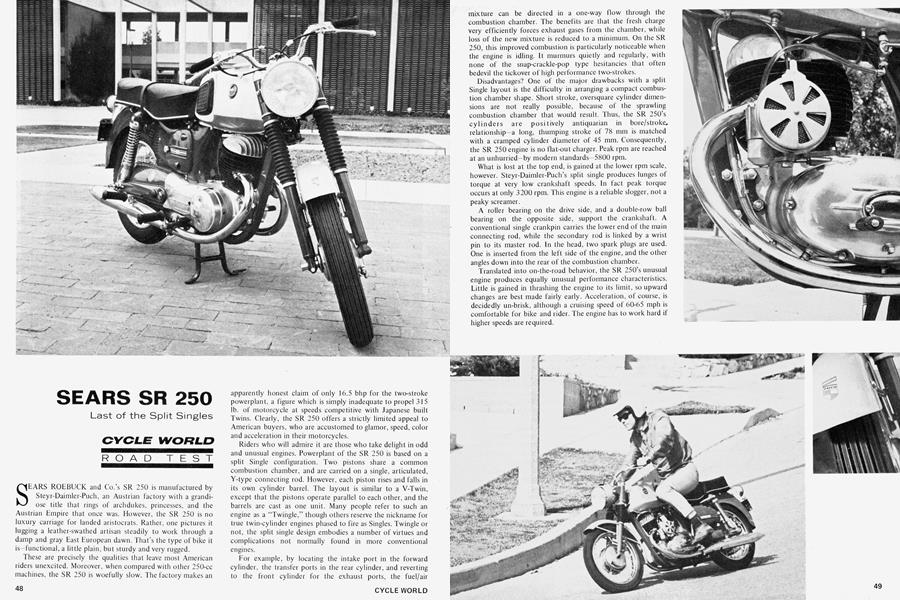

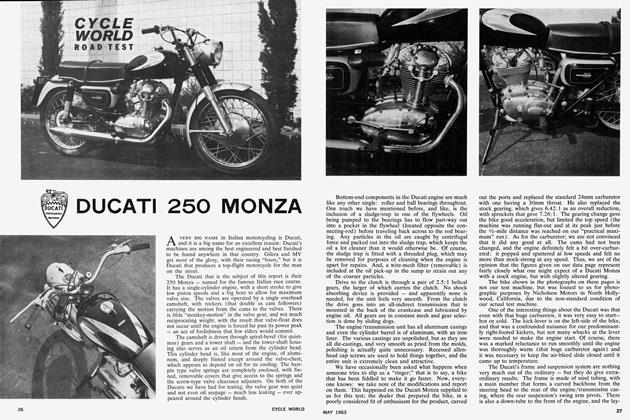

SEARS ROEBUCK and Co.'s SR 250 is manufactured by Steyr-Daimler-Puch, an Austrian factory with a grandiose title that rings of archdukes, princesses, and the Austrian Empire that once was. However, the SR 250 is no luxury carriage for landed aristocrats. Rather, one pictures it lugging a leather-swathed artisan steadily to work through a damp and gray East European dawn. That's the type of bike it is—functional, a little plain, but sturdy and very rugged.

These are precisely the qualities that leave most American riders unexcited. Moreover, when compared with other 250-cc machines, the SR 250 is woefully slow. The factory makes an apparently honest claim of only 16.5 bhp for the two-stroke powerplant, a figure which is simply inadequate to propel 315 lb. of motorcycle at speeds competitive with Japanese built Twins. Clearly, the SR 250 offers a strictly limited appeal to American buyers, who are accustomed to glamor, speed, color and acceleration in their motorcycles.

Riders who will admire it are those who take delight in odd and unusual engines. Powerplant of the SR 250 is based on a split Single configuration. Two pistons share a common combustion chamber, and are carried on a single, articulated, Y-type connecting rod. However, each piston rises and falls in its own cylinder barrel. The layout is similar to a V-Twin, except that the pistons operate parallel to each other, and the barrels are cast as one unit. Many people refer to such an engine as a "Twingle," though others reserve the nickname for true twin-cylinder engines phased to fire as Singles. Twingle or not, the split single design embodies a number of virtues and complications not normally found in more conventional engines.

For example, by locating the intake port in the forward cylinder, the transfer ports in the rear cylinder, and reverting to the front cylinder for the exhaust ports, the fuel/air mixture can be directed in a one-way flow through the combustion chamber. The benefits are that the Iresh charge very efficiently forces exhaust gases from the chamber, while loss of the new mixture is reduced to a minimum. On the SR 250, this improved combustion is particularly noticeable when the engine is idling. It murmurs quietly and regularly, with none of the snap-crackle-pop type hesitancies that olten bedevil the tickover of high performance two-strokes.

Disadvantages? One of the major drawbacks with a split Single layout is the difficulty in arranging a compact combustion chamber shape. Short stroke, oversquare cylinder dimensions are not really possible, because of the sprawling combustion chamber that would result. Thus, the SR 250's cylinders are positively antiquarian in bore/stroke., relationship-a long, thumping stroke of 78 mm is matched with a cramped cylinder diameter of 45 mm. Consequently, the SR 250 engine is no flat-out charger. Peak rpm are reached at an unhurried-by modern standards—5800 rpm.

What is lost at the top end, is gained at the lower rpm scale, however. Steyr-Daimler-Puch's split single produces lunges of torque at very low crankshaft speeds. In fact peak torque occurs at only 3200 rpm. This engine is a reliable slogger, not a peaky screamer.

A roller bearing on the drive side, and a double-row ball bearing on the opposite side, support the crankshaft. A conventional single crankpin carries the lower end ol the main connecting rod, while the secondary rod is linked by a wrist pin to its master rod. In the head, two spark plugs are used. One is inserted from the left side of the engine, and the other angles down into the rear of the combustion chamber.

Translated into on-the-road behavior, the SR 250's unusual engine produces equally unusual performance characteristics. Little is gained in thrashing the engine to its limit, so upward changes are best made fairly early. Acceleration, of course, is decidedly un-brisk, although a cruising speed of 60-65 mph is comfortable for bike and rider. The engine has to work hard it higher speeds are required.

One very modern piece of equipment that the SR 250 has boasted for some years is an oil injection system. This is commonplace today, but it was teatured on Sears' bike when such a system was regarded as a luxury. The oil pump is driven from the crankshaft by a worm gear arrangement, and also is linked to the throttle opening. Rate of oil feed easily is adjusted, after removing a small plate on the upper left crankcase. The maker, however, suggests that the standard setting will suit all uses, and discouraged experimentation with the pump.

Where the bike's East European lineage really shows is in finish and construction. Everything is exceptionally solid, absolutely adequate, designed apparently without much attention to weight-saving measures. The black-finned engine is surrounded by a pressed steel frame that appears as though it would survive years of abuse over unpaved mountain roads. An exception to the steel pressings is the tube that extends in front of and underneath the engine. The bodywork houses compartments for the 6-V battery, and for tools. The toolbox is a massive cubicle with extra room for maps, food, a small drink container, or other small objects.

The toolkit itself includes an impressive array of equipment, more than necessary to attend to minor servicing operations. The Austrian factory obviously expects its product to be used in areas where service stations do not occur every mile.

Fenders are formed of steel, and fully intended to keep water and muck where it should be-away from the rider and engine. The rear unit, in particular, is a massive piece of steelwork with deep valances that extend downward on each side of the tire. Footpegs are sturdy and wide, and the tank is a steel box-like affair that, nevertheless, is undeniably handsome. One side houses 3.35 gal. of fuel, while 1.5 pt. of oil are stored in the left compartment. Paintwork is a pleasant mixture of deep red, and battleship gray.

More evidence that the SR 250 is designed to work for long periods without breaking lies in the totally enclosed rear chaincase. Hidden in a steel compartment, the chain can perform its task of transferring drive from gearbox to rear wheel without interference from the life-shortening effects of water, grit, mud and dust. Such chaincases were common on motorcycles a few years ago, but are less frequent in these days of emphasis on light weight and sporting appearances.

Thoughtful, too, is the attention given to control cables. Soft metal clips secure clutch and oil pump cables, and an oil line, to the frame downtube—a neat arrangement that avoids an untidy mass of cables flapping in the wind or abrading themselves on metal edges. Throttle, clutch, front brake, and oil pump cables also are provided, near the control lever junctions, with plastic housings that enable the cable body to be lubricated. A little flap on each housing permits an oil can to penetrate the cable.

Clutch and gearbox action indicates these components also are pretty strongly made. The clutch is a conventional unit, with seven plates, and a determined pull is needed to operate the lever. The gear pedal is mounted on the left, and shifts on a one-down, three-up pattern. Movements are short, but the action is clunky and slow on both up and down shifts.

Suspension is by a conventional telescopic fork at the front, with rear swinging arm and coil spring/shock absorber units. The handling is adequate for any tasks the SR 250 will be set-its top speed capabilities save it from attempting any curves at much over 70 mph. Low speed handling seems a little heavy on the front end, a sensation which could be a result of a fairly high center of gravity, combined with a short handlebar. On a faster machine, the brakes might leave something to be desired; on the Sears, they perform without fault.

Starting is almost foolproof. With ignition switch and fuel tap on, choke closed and carburetor flooded, one or two kicks are sufficient to fire the engine from cold. The carburetor, a big 32-mm Puch unit, is perched well out on the left beside the cylinder barrels, and is fed through a rather skimpy wire mesh air filter, enclosed in a circular plastic holder. The choke control is comprised of a plastic disc with cutouts which match similar vents in the holder face. To stop the air supply, the disc simply is rotated until all the cutouts are blanked off. This device seems to arouse laughter from nearly everyone who sees it. Just why, is a mystery. The choke may be a toy-like device, but it's simple, cheap to make, foolproof, and effective.

Ownership of an SR 250 could never be a stirring experience. The bike is rather slow and not at all brisk, but, on the other hand, it possesses no glaring faults. Sears delivers the machine in a crate, and the buyer assembles the handlebar and controls, attaches the footrests, fills the battery with distilled water, and supplies the gearbox oil. Full instructions for these simple operations are contained in a comprehensive service and spares manual. If anyone is in search of daily transport that combines reliability, durability, and longevity, he will find it in the SR 250—in full value.

SEARS

SR 250

$595