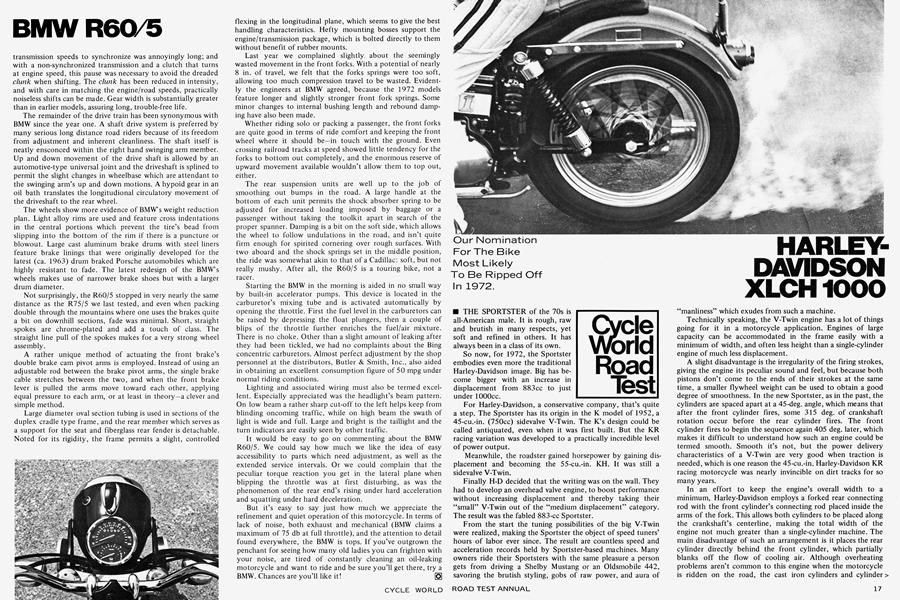

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLCH 1000

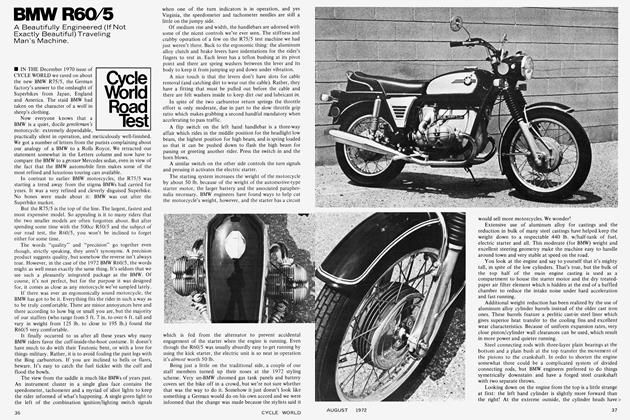

Cycle World Road Test

Our Nomination For The Bike Most Likely To Be Ripped Off In 1972.

THE SPORTSTER of the 70s is all-American male. It is rough, raw and brutish in many respects, yet soft and refined in others. It has always been in a class of its own.

So now, for 1972, the Sportster embodies even more the traditional Harley-Davidson image. Big has become bigger with an increase in displacement from 883cc to just under 1000cc.

For Harley-Davidson, a conservative company, that’s quite a step. The Sportster has its origin in the K model of 1952, a 45-cu.-in. (750cc) sidevalve V-Twin. The K’s design could be called antiquated, even when it was first built. But the KR racing variation was developed to a practically incredible level of power output.

Meanwhile, the roadster gained horsepower by gaining displacement and becoming the 55-cu.-in. KH. It was still a sidevalve V-Twin.

Finally H-D decided that the writing was on the wall. They had to develop an overhead valve engine, to boost performance without increasing displacement and thereby taking their “small” V-Twin out of the “medium displacement” category. The result was the fabled 883-cc Sportster.

From the start the tuning possibilities of the big V-Twin were realized, making the Sportster the object of speed tuners’ hours of labor ever since. The result are countless speed and acceleration records held by Sportster-based machines. Many owners ride their Sportsters with the same pleasure a person gets from driving a Shelby Mustang or an Oldsmobile 442, savoring the brutish styling, gobs of raw power, and aura of “manliness” which exudes from such a machine.

Technically speaking, the V-Twin engine has a lot of things going for it in a motorcycle application. Engines of large capacity can be accommodated in the frame easily with a minimum of width, and often less height than a single-cylinder engine of much less displacement.

A slight disadvantage is the irregularity of the firing strokes, giving the engine its peculiar sound and feel, but because both pistons don’t come to the ends of their strokes at the same time, a smaller flywheel weight can be used to obtain a good degree of smoothness. In the new Sportster, as in the past, the cylinders are spaced apart at a 45-deg. angle, which means that after the front cylinder fires, some 315 deg. of crankshaft rotation occur before the rear cylinder fires. The front cylinder fires to begin the sequence again 405 deg. later, which makes it difficult to understand how such an engine could be termed smooth. Smooth it’s not, but the power delivery characteristics of a V-Twin are very good when traction is needed, which is one reason the 45-cu.-in. Harley-Davidson KR racing motorcycle was nearly invincible on dirt tracks for so many years.

In an effort to keep the engine’s overall width to a minimum, Harley-Davidson employs a forked rear connecting rod with the front cylinder’s connecting rod placed inside the arms of the fork. This allows both cylinders to be placed along the crankshaft’s centerline, making the total width of the engine not much greater than a single-cylinder machine. The main disadvantage of such an arrangement is it places the rear cylinder directly behind the front cylinder, which partially blanks off the flow of cooling air. Although overheating problems aren’t common to this engine when the motorcycle is ridden on the road, the cast iron cylinders and cylinder heads often haven’t been able to get rid of the heat developed in racing versions, and seizures and piston failures aren’t rare.

Many foreign machine buffs have likened the Harley-Davidson line to Peterbuilt diesel trucks and Euclid earthmovers, looking down their noses at the rough engine castings and purposeful frame lugs. But there’s a reason behind it all: strength. Take the lower engine section. The machined cast iron flywheel assembly which runs on conventional roller bearings on the timing (right-hand) side and massive Timken tapered roller bearings on the drive side tell you this machine was built to take abuse for long periods of time. Three rows of roller bearings support the male (front) and female (rear) connecting rods, and needle roller bearings carry the loads of the four cam gears, one for each valve. An inspection hole is provided near the top left-hand side of the crankcase exposing two timing marks which are scribed onto the flywheel for timing the Twin with a strobe light. Roller tappet cam followers help reduce the noise of the valve mechanism and ensure long life of the cams.

A massive triple-row primary chain transmits the engine’s power impulses to the wet clutch from the crankshaft’s compensating sprocket which contains little more than a large spring. This sprocket acts as a shock absorber when the engine revs are low or the clutch is let out, to ease the sudden load put on the chains and transmission components.

After several years of suffering through the agonies of trying to keep the dry-type clutch dry when running it in an oil bath, Harley-Davidson finally went to a wet-type clutch for the 1971 models, which has worked very well. Lining material for the drive plates is similar to that of the automobile automatic transmissions. It made a slightly rough engagement during the first couple hundred miles of our fest but began to disappear when we returned the machine.

The wet clutch tended to drag slightly if the bike was not completely warmed up because the transmission oil supply is shared by the clutch and primary chain and is the same weight of oil used in the engine. Once the oil had a chance to warm up, however, we had no further clutch problems, even after several full-throttle acceleration runs.

A feature most of us liked was the primary gear kickstarter, which allows the machine to be started in any gear as long as the clutch lever is withdrawn. Those of us used to riding British machines were loath to admit that this system is a good one because of our habit of withdrawing the clutch lever and running the kickstarter through a couple of times to make sure the clutch plates were free.

Clutch lever pressure is only slightly greater than that of last year in spite of a pressure increase in the two huge, single-coil clutch springs from 150 lb. to 234 lb. Even with the increased spring poundage and redesigned clutch actuating mechanism, which has lessened the amount of clutch disengagement relative to the amount of lever travel, there was plenty of lever travel between the period when the clutch was fully engaged and when it was fully disengaged.

Whatever people have criticized about the Harley-Davidson, not much bad has been said about the transmission, which is often called the best in the business. Although very straightforward in design, the constant-mesh transmission’s gears are large and strong enough to be installed in a Mack truck, and rarely give any trouble. If there is trouble, the entire transmission may be dismantled without removing the engine from the frame and splitting the crankcases. In recent years the only problems have been when the spring-loaded plungers, which press on the gear shifter cam to hold the bike in gear, pick up a tiny sliver of metal, causing the plungers to stick in position, usually with the machine in high gear! For 1972, the plungers have been redesigned and relocated to preclude this occurrence.

Shifting is effortless in either direction. Even though the government has decided that everybody will have to shift with their left foot in the future, we liked the right-hand, British-pattern, down-for-low shift sequence of the Sportster. Gear lever travel is moderately long, but the gears engage positively with very little noise and not too much lever pressure. Several years ago, Harley-Davidson replaced the serrated shift lever shaft and shift lever with smooth ones to prevent damage to the internal shifting mechanism from over-zealous shifting and misuse.

However easily the Sportster shifts, at least two of our testers had doubts about the choice of the internal gearbox ratios. As with many large-bore motorcycles these days, Harley-Davidson has installed a rather low (numerically high) overall gear ratio for better acceleration and improved aroundtown performance which seems well suited to the engine’s power characteristics. However, the first three gears are a trifle close together with too big a jump to fourth. It would be better to have the biggest jump between first and second, and a slightly higher overall gear ratio for more sedate highway cruising.

Much of the new Sportster’s appeal lies in its increase in piston displacement from 883cc (53.9 cu. in.) to 997.5cc (60.9 cu. in.). This increase in size, accomplished by fitting larger bore cylinders, necessitated moving the cylinder holddown bolts farther apart. Sorry, you can’t bolt the new Sportster cylinders and heads to your 1971 or earlier XLCH! Even with an increase in bore size of almost 5mm, the Sportster is still decidedly “undersquare.” Piston speed at 6500 rpm is a rather high 4100-plus feet/min., but then the Sportster was not designed with high rpm in mind. Rather, the goal was to have a broad, flat power range with high reliability, which it most certainly has.

The Sportster also hauls ass. With the California mufflers in place, the bike ripped off a 13.38-sec. quarter mile at 97.71 mph. To get an idea of how restrictive those mufflers are, we removed the mufflers and substituted a straight pipe arrangement. Fattening up the jets, we ripped off a score of 12s. The best was 12.76 sec. at 102.62 mph. But the mufflers-on figure must go into the data panel, for that’s the way CYCLE WORLD tests everything else.

Very little change has been made to the existing cylinder head and valve arrangement, but the earlier Tillotson carburetor which had three separate, and often confusing, mixture adjustments has been replaced with a Bendix/Zenith instrument with only one visible adjustment. Although this knob is called a “low-speed” needle, it actually varies the mixture strength at all except the widest throttle openings.

A fault of the Tillotson carburetor was its tendency to vapor-lock in hot weather in spite of the fact that it was separated from the inlet manifold by a thick phenolic insulating block. The new Bendix/Zenith carburetor does not require an insulator block and is therefore in closer to the engine. The air cleaner still sticks out enough that you can hit your leg on it, but the reduction in width in that area is welcome. An improved accelerator pump is featured on the Bendix/Zenith carburetor to provide instant acceleration when the throttle is blipped open, but it will flood the engine if the throttle is opened and closed while the engine is shut off, or if you pump the throttle during the starting operation.

Starting the XLCH is easy if the proper sequence is followed when the engine is cold, and it is a one-kick affair once the machine has had a chance to warm up. With 9.0:1 compression ratio and one-liter piston displacement, it takes a healthy prod on the kickstarter to get the engine turning over, but the automatic advance coil and battery ignition system provide a good spark at low cranking speeds and aid the starting chore considerably. Once running, the XLCH settles down to its characteristic lumpety-lump idle and warms up fairly quickly. A slightly redesigned ignition point cam adds to the life of the points and allegedly makes starting easier.

Mechanical and exhaust noise are both very low for a machine of this size, but the exhaust noise reduction has been at the expense of performance. California and a few cities in the Eastern U.S. have rather restrictive noise laws (86 dB maximum) which made it necessary for Harley-Davidson to come up with a really quiet muffler. This they did, but the Sportster’s strange looking silencer provides a great amount of back pressure with less than pleasing looks. Particularly unattractive are the seams where the vertical muffler halves are welded together, and the rather strange looking shape.

At highway speeds, the XLCH is very quiet and docile with only a slight clatter from the valve gear and a subdued purr from the exhaust. Vibration is also very low, both in amplitude and severity. An increase in engine speed to 6000 rpm brought both up to a less comfortable level. But this is the first Sportster in history that we’d consider for a 400-mile-aday trip.

Commendable is the Sportster engine’s oil tightness. A weep appeared at a couple of the rocker arm ends, and a slight stream emerged from the tachometer drive on the engine case, but the rest of the machine remained oil tight for the duration of the test. The tendency for a Sportster to “wet-sump” (retain too much oil in the crankcase) has been eliminated by the installation of a different oil pump with larger scavenge gears and oil passages. Normal running oil pressure is 10-14 psi, but even this rather low figure is sufficient to circulate the oil for cooling and lubricating the engine.

For the most part, the handlebars are comfortable for cruising down the highway, but are swept back rather more than most of us liked. Control placement was judged good and the clutch and brake levers are comfortable to the hand.

What has traditionally irritated us is the method of operation and the action of the throttle linkage. Big Harleys have used a push/pull arrangement for many years with no positive automatic return to the idle position. It’s good for highway running, as the throttle can be set at any position and left there with no pressure on the hand grip, making long trips a pleasure. However, the throttle assembly has a lot of slack in it and getting a fine speed adjustment on such a powerful motorcycle took a good deal of patience and/or luck to hit it right the first time. And, we felt it would be nice to have the engine return to idle in the event of a spill.

Since seats are very personal items with Sportster owners, the factory has fitted a “custom” one as standard equipment, fully expecting the owner to change it anyway. It is thin, narrow and uncomfortable for anything more than a trip around town, although it looks pretty sharp! The horn is loud, but the outlet is cleverly pointed down at the primary chaincase so the sound reflects right back up into your left ear when you use it. The main reason this seems so annoying is that most motorcycle horns just aren’t loud enough to do much good, but this certainly isn’t the case with the Sportster. The headlight dipper switch is located on the front of the left handlebar and takes getting used to, and the ignition switch has been moved to a location just above the horn. Another click of the switch turns on the lights.

The use of American electrical components (with the exception of the German-made Bosch voltage regulator) should give a clue to the reliability of the electrical system. In spite of some wiring location faults, we could find nothing to complain about except the size of the rather smallish headlight. Night cruising is fun, but a little more light up front would make it nicer.

Now, the Sportster could hardly be called a road racer, but it does handle well in average “70 percent” cruising situations. In a straight line, it’s like the Rock of Gibraltar. In turns, you ease it through, not throw it, but it doesn’t play foul tricks. The telescopic front forks provide generous travel for a road machine, and although they were still a little stiff when we returned the machine, they were showing signs of loosening up to where we like to have them. Railroad crossings and roads in bad repair could be traversed with the confidence that the front end wasn’t going to do anything strange. The spring rate was ideal for a 165-lb. rider and felt good with a passenger aboard. The rear shocks were also a trifle stiff in their action, but the spring rate was perfect for a medium-weight rider. Three cam adjustments provide differing spring rates for packing double or for a heavier rider, but a special tool must be purchased from the dealer to adjust them.

As with all the Harleys manufactured in America, the double-cradle frame is quite crude in appearance. Rough castings at the steering head and seat mounting points look as though they were installed in an “as cast” condition. Welding on the frame is first rate, and the high weight of the frame is not so bad when one considers how much of a load it is actually carrying. It still lacks rigidity, which shows up as residual waggle when the bike is yanked from turn to turn.

Handling belies the machine’s almost 500-lb. weight—until slow-moving traffic indicates the machine is slightly “topheavy” when rounding slow corners. Part of this feeling is attributable to the generous rake and trail measurements which make the machine handle so well at speed, a tradeoff we agree with.

The braking department has not been altered since the last Sportster we tested, and again we think that more braking is in order. With more than 63 in. of brake swept area, and a brake loading of just under 8 lb./sq. in. (with the machine unladen), it would seem that the brakes would be really good. Well, they’re not bad for the first stop or two, but the single leading-shoe unit on the front heats up and fades badly after a couple hard applications, and the rear unit always feels spongy, but does its share of bringing the bike to a halt. We would much prefer to see the Sportster equipped with a version of the disc brake being used on the 1972 74-cu.-in. Harley-Davidsons. No, the XLCH isn’t a racer by any stretch of the imagination, but a machine capable of 13-sec. quartermiles should have better brakes.

As with all American Harleys, the finish is excellent, with the exception of the rough castings mentioned earlier. The painted fenders and small gas tank are flawless and the lustrous black enamel on the frame is reluctant to chip. Chrome is likewise fine, and we note that all the Sportsters are coming equipped with the steel taper base wheel rims specially designed to accept specially designed Goodyear tires. These rim/tire combinations work together to help keep the tire on the rim in case of a blowout, aiding machine controllability immensely.

Other likeable touches: the large, easy-to-read speedometer/tachometer combination and the rubber-mounted handlebars, which help take the tingle out of a long trip. The front safety reflectors are stuck unobtrusively on the front fender mounts, and the battery fluid level is easily visible through the transparent battery sides.

Not so likeable: the “padlock-type” front fork lock. And the shell encasing the speedometer/tachometer combination should be painted a matte black to reduce the light reflected into the rider’s eyes on a sunny day.

The Sportster still has its charm and following, and the highish price will gladly be paid by those who want a rugged, high-quality product. And it is much easier to live with.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

XLCH1000

List price .........................$2136