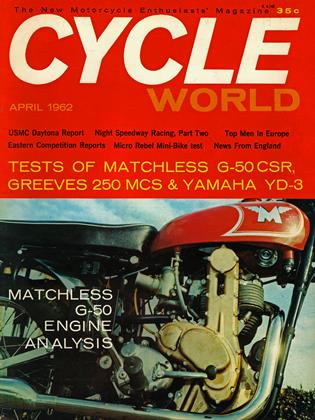

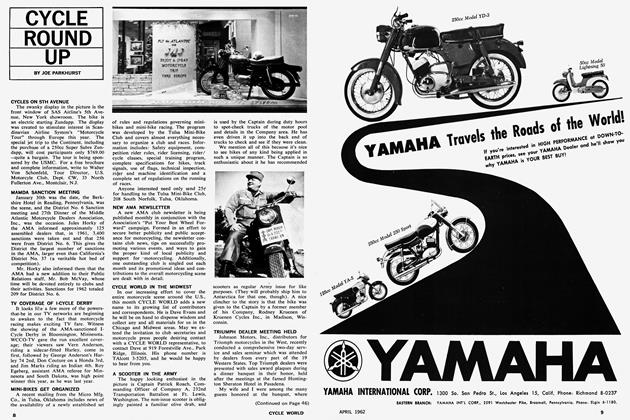

YAMAHA YD-3

Cycle World Road Test

ONCE UPON A TIME, Japanese - manufactured goods were mostly bargain-basement copies of pro ducts originating in the technically more sophisticated western countries. However, with the reformation of Japan's industrial complex after the unpleasantness of the forties, there has been a drastic change.

Japan still produces at prices that are hard to match, but now it is primarily because their factories are heavily automated, and the products themselves are often of unsurpassed quality. Optical and electronic equipment are the things most often mentioned as outstanding examples of advancing Japanese technology, which they certainly are, but we would like to add just one more item: motorcycles. And, among Japan's two-wheelers, one of the very best is the Yamaha.

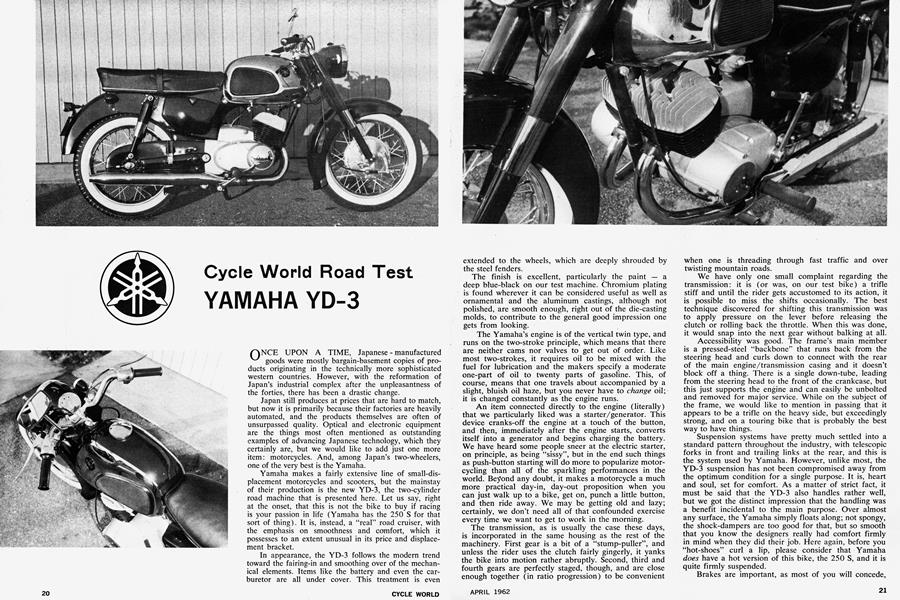

Yamaha makes a fairly extensive line of small-dis placement motorcycles and scooters, but the mainstay of their production is the new YD-3, the two-cylinder road machine that is presented here. Let us say, right at the onset, that this is not the bike to buy if racing is your passion in life (Yamaha has the 250 S for that soit of thing). It is, instead, a "real" road cruiser, with the emphasis on smoothness and comfort, which it possesses to an extent unusual in its price and displace ment bracket.

In appearance, the YD-3 follows the modern trend toward the fairing-in and smoothing over of the mechan ical elements. Items like the battery and even the car buretor are all under cover. This treatment is even extended to the wheels, which are deeply shrouded by the steel fenders.

The finish is excellent, particularly the paint — a deep blue-black on our test machine. Chromium plating is found wherever it can be considered useful as well as ornamental and the aluminum castings, although not polished, are smooth enough, right out of the die-casting molds, to contribute to the general good impression one gets from looking.

The Yamaha’s engine is of the vertical twin type, and runs on the two-stroke principle, which means that there are neither cams nor valves to get out of order. Like most two-strokes, it requires oil to be mixed with the fuel for lubrication and the makers specify a moderate one-part of oil to twenty parts of gasoline. This, of course, means that one travels about accompanied by a slight, bluish oil haze, but you never have to change oil; it is changed constantly as the engine runs.

An item connected directly to the engine (literally) that we particularly liked was a starter/generator. This device cranks-off the engine at a touch of the button, and then, immediately after the engine starts, converts itself into a generator and begins charging the battery. We have heard some people sneer at the electric starter, on principle, as being “sissy”, but in the end such things as push-button starting will do more to popularize motorcycling than all of the sparkling performances in the world. Beÿond any doubt, it makes a motorcycle a much more practical day-in, day-out proposition when you can just walk up to a bike, get on, punch a little button, and then ride away. We may be getting old and lazy; certainly, we don’t need all of that confounded exercise every time we want to get to work in the morning.

The transmission, as is usually the case these days, is incorporated in the same housing as the rest of the machinery. First gear is a bit of a “stump-puller”, and unless the rider uses the clutch fairly gingerly, it yanks the bike into motion rather abruptly. Second, third and fourth gears are perfectly staged, though, and are close enough together (in ratio progression) to be convenient

when one is threading through fast traffic and over twisting mountain roads.

We have only one small complaint regarding the transmission: it is (or was, on our test bike) a trifle stiff and until the rider gets accustomed to its action, it is possible to miss the shifts occasionally. The best technique discovered for shifting this transmission was to apply pressure on the lever before releasing the clutch or rolling back the throttle. When this was done, it would snap into the next gear without balking at all.

Accessibility was good. The frame’s main member is a pressed-steel “backbone” that runs back from the steering head and curls down to connect with the rear of the main engine/transmission casing and it doesn’t block off a thing. There is a single down-tube, leading from the steering head to the front of the crankcase, but this just supports the engine and can easily be unbolted and removed for major service. While on the subject of the frame, we would like to mention in passing that it appears to be a trifle on the heavy side, but exceedingly strong, and on a touring bike that is probably the best way to have things.

Suspension systems have pretty much settled into a standard pattern throughout the industry, with telescopic forks in front and trailing links at the rear, and this is the system used by Yamaha. However, unlike most, the YD-3 suspension has not been compromised away from the optimum condition for a single purpose. It is, heart and soul, set for comfort. As a matter of strict fact, it must be said that the YD-3 also handles rather well, but we got the distinct impression that the handling was a benefit incidental to the main purpose. Over almost any surface, the Yamaha simply floats along; not spongy, the shock-dampers are too good for that, but so smooth that you know the designers really had comfort firmly in mind when they did their job. Here again, before you “hot-shoes” curl a lip, please consider that Yamaha does have a hot version of this bike, the 250 S, and it is quite firmly suspended.

Brakes are important, as most of you will concede, and on the Yamaha they are worth a special mention. If anything, these brakes are too good; when you use them hard the first time, you begin to wonder if the wheels have not suddenly rolled into a lake of cold mo lasses. There is no shuddering, no wheel-hop, and not much need for clamping down hard. Indeed, if you apply too much pressure, it is possible to come danger ously near locking the front wheel. Even so, we were enormously impressed with the Yamaha's stopping power, and our standards regarding braking perform ance are higher for having ridden this machine. A final note: the YD-3 has very large aluminum brake drums, and it is inconceivable that these would fade under any conditions even approaching being normal for the machine.

During the testing of the Yamaha YD-3, we actually used the bike for transportation - to and from the office, and on weekend pleasure jaunts. For that sort of use it is grand. It starts every time, at a touch of the handle bar-mounted button, and the equipment includes such niceties as flashing turn-indicators - very handy in traffic. One "nicety" that brought forth a bit of unusual conversation was the use of white sidewall tires, a not too common sight on motorcycles. Some mountain mile age was included, during which we discovered the basically good balance of the YD-3. The suspension is soft, as we said, but as long as you use a bit of restraint on banked, bumpy turns, this bike will get around in a most satisfactory manner.

YAMAHA

YD-3

SPECIFICATIONS

$549

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Service Department

April 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Cycle Round Up

April 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

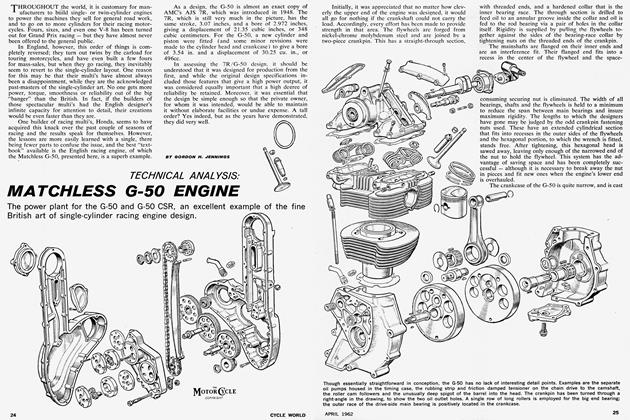

Technical Analysis: Matchless G-50 Engine

April 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

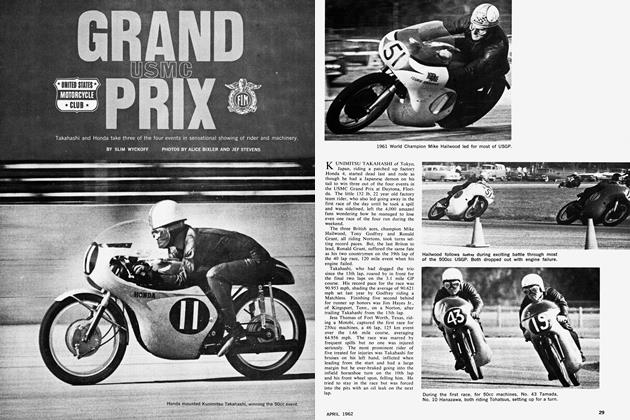

Grand Usmc Prix

April 1962 By Slim Wyckoff -

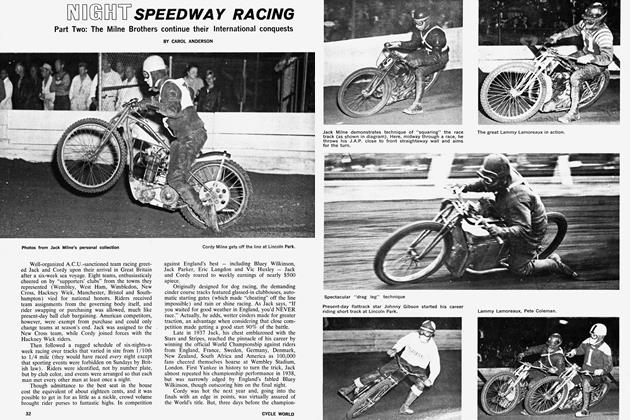

Night Speedway Racing

April 1962 By Carol Anderson -

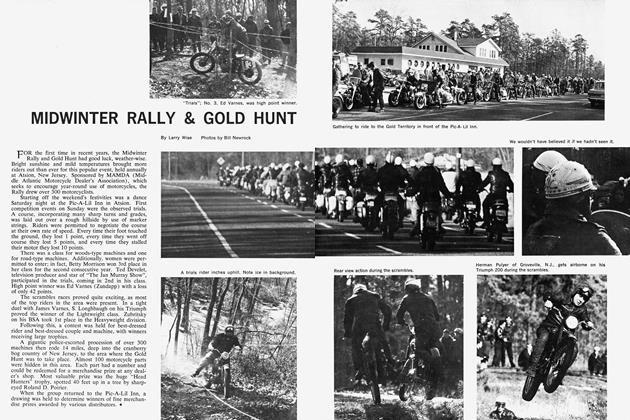

Midwinter Rally & Gold Hunt

April 1962 By Larry Wise