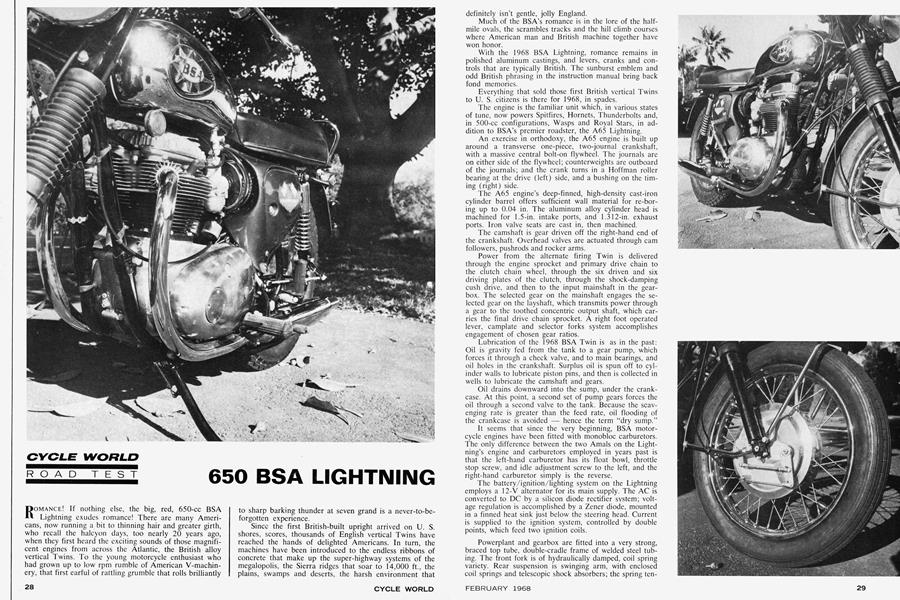

650 BSA LIGHTNING

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

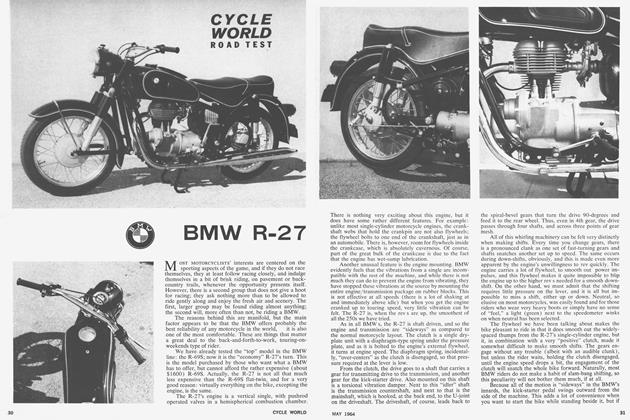

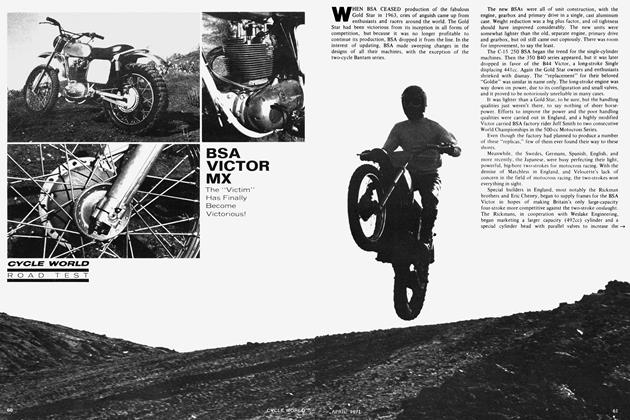

ROMANCE! If nothing else, the big, red, 650-cc BSA Lightning exudes romance! There are many Americans, now running a bit to thinning hair and greater girth, who recall the halcyon days, too nearly 20 years ago, when they first heard the exciting sounds of those magnificent engines from across the Atlantic, the British alloy vertical Twins. To the young motorcycle enthusiast who had grown up to low rpm rumble of American V-machinery, that first earful of rattling grumble that rolls brilliantly to sharp barking thunder at seven grand is a never-to-be-forgotten experience.

Since the first British-built upright arrived on U. S. shores, scores, thousands of English vertical Twins have reached the hands of delighted Americans. In turn, the machines have been introduced to the endless ribbons of concrete that make up the super-highway systems of the megalopolis, the Sierra ridges that soar to 14,000 ft., the plains, swamps and deserts, the harsh environment that definitely isn’t gentle, jolly England.

Much of the BSA’s romance is in the lore of the halfmile ovals, the scrambles tracks and the hill climb courses where American man and British machine together have won honor.

With the 1968 BSA Lightning, romance remains in polished aluminum castings, and levers, cranks and controls that are typically British. The sunburst emblem and odd British phrasing in the instruction manual bring back fond memories.

Everything that sold those first British vertical Twins to U. S. citizens is there for 1968, in spades.

The engine is the familiar unit which, in various states of tune, now powers Spitfires, Hornets, Thunderbolts and, in 500-cc configurations, Wasps and Royal Stars, in addition to BSA’s premier roadster, the A65 Lightning.

An exercise in orthodoxy, the A65 engine is built up around a transverse one-piece, two-journal crankshaft, with a massive central bolt-on flywheel. The journals are on either side of the flywheel; counterweights are outboard of the journals; and the crank turns in a Hoffman roller bearing at the drive (left) side, and a bushing on the timing (right) side.

The A65 engine’s deep-finned, high-density cast-iron cylinder barrel offers sufficient wall material for re-boring up to 0.04 in. The aluminum alloy cylinder head is machined for 1.5-in. intake ports, and 1.312-in. exhaust ports. Iron valve scats are cast in, then machined.

The camshaft is gear driven off the right-hand end of the crankshaft. Overhead valves are actuated through cam followers, pushrods and rocker arms.

Power from the alternate firing Twin is delivered through the engine sprocket and primary drive chain to the clutch chain wheel, through the six driven and six driving plates of the clutch, through the shock-damping cush drive, and then to the input mainshaft in the gearbox. The selected gear on the mainshaft engages the selected gear on the layshaft, which transmits power through a gear to the toothed concentric output shaft, which carries the final drive chain sprocket. A right foot operated lever, camplate and selector forks system accomplishes engagement of chosen gear ratios.

Lubrication of the 1968 BSA Twin is as in the past: Oil is gravity fed from the tank to a gear pump, which forces it through a check valve, and to main bearings, and oil holes in the crankshaft. Surplus oil is spun off to cylinder walls to lubricate piston pins, and then is collected in wells to lubricate the camshaft and gears.

Oil drains downward into the sump, under the crankcase. At this point, a second set of pump gears forces the oil through a second valve to the tank. Because the scavenging rate is greater than the feed rate, oil flooding of the crankcase is avoided — hence the term “dry sump.”

It seems that since the very beginning, BSA motorcycle engines have been fitted with monobloc carburetors. The only difference between the two Amals on the Lightning’s engine and carburetors employed in years past is that the left-hand carburetor has its float bowl, throttle stop screw, and idle adjustment screw to the left, and the right-hand carburetor simply is the reverse.

The battery/ignition/lighting system on the Lightning employs a 12-V alternator for its main supply. The AC is converted to DC by a silicon diode rectifier system; voltage regulation is accomplished by a Zener diode, mounted in a finned heat sink just below the steering head. Current is supplied to the ignition system, controlled by double points, which feed two ignition coils.

Powerplant and gearbox are fitted into a very strong, braced top tube, double-cradle frame of welded steel tubing. The front fork is of hydraulically damped, coil spring variety. Rear suspension is swinging arm, with enclosed coil springs and telescopic shock absorbers; the spring tension can be varied with a three-position cam adjuster at the lower end of each spring/shock.

The rear brake unit is a cast-iron drum with aluminum alloy shoes. The front brake is new, to BSA at least, for 1968. This unit, shared with cross-corporate Triumph machines, is of the double leading shoe variety, with the full-floating feature that permits pivoting shoes to seek their own center for full contact braking efficiency.

There it is, a BSA Lightning from the ground up, British as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, American as the millions of miles of U. S. roadway Birmingham Small Arms machines have traveled.

And, travel with the BSA Lightning is what the machine is all about.

The Lightning under test by CW did not fail to fire on first kick (given one ignition-off turnover for priming), even on the briskest of mornings.

Threading the green light/red light, stop-and-go congestion of urban traffic proved the Lightning is a docile creature, willing to accommodate its human partner. The machine is an obedient servant for the run to the bank, the barber shop, or the ballgame. But this sort of dogsbody work isn’t the true forte of the Lightning.

Freeway or wide open secondary road, where the rider can maintain his cruise at top legal speed, is Lightning’s home environment. A freeway run between cities some distance apart is a pleasurable experience on the BSA Lightning, as well as a rapid means of transport from Point A to Point B.

Rated at 54.7 bhp, and delivering 42.6 lb.-ft. of torque at 7000 rpm, the 650-cc BSA engine seems more than adequate for two-up and/or cargo hauling operations. At a rapid cruise, the steepest of hills becomes simply a change-down-to-third situation. In all certainty, the BSA Lightning has the capability to go, to run quickly over sustained periods of time.

CYCLE WORLD'S accompanying acceleration graph for the BSA Lightning may not be as spectacular as those which appear in other publications. (One magazine already has published a graph that shows the Lightning is capable of speed greater than carburetion, mathematics, top bhp, or gearing will permit. Thus the conclusion must be drawn that either the machine or the magazine’s figures were fiddled.) Comparing CW’s test Lightning’s quarter-mile performance with that of other, similar 650-cc machines, shows this particular bike is neither exceptionally quick, nor excessively slow. Actual top speed of 102 mph is not to be sneezed at (or to be used on public streets and highways).

The Lightning’s handling characteristics can be described as neither the lightest nor the heaviest ever encountered. A certain degree of effort is required to manage the Lightning through a series of curves.

Braking quality of the BSA Lightning is stronger than most machines, less formidable than others. The test machine’s front brake unit tended to shudder when placed under the duress of an all-on stop, yet riders experienced no lack of braking efficiency, or loss of directional control or stability.

In the first 500 miles of test riding, only the choke cable ferrule jumped its socket, a passenger footpeg vibrated loose and, as always, the center stand foot rubber 'wore through on the first grounding at the first fast lefthand bend.

A point of gross irritation was discovered when battery and toolbox covers were removed in a routine inspection of the machine. The molded fiberglass covers are secured to the machine with a British version of Dzus fasteners, slot-head, spring-clip retainers used primarily in aircraft applications. Spring tension on the Lightning’s fasteners was such that either exceptionally strong fingers on a large coin or a screwdriver was required to gain access to the battery or toolbox. Replacing the covers was a task of equal difficulty.

The BSA Lightning can be regarded as representing the British standard in touring machinery. However, in analysis, the Lightning suffers in the harsh light of engineering comparison. The BSA, with its special sound, the romance of a product from across the sea, displays a severe lack of that evolutionary development which is apparent among other machines — from Germany, Japan, and Italy.

It seems typically British that once a product is produced and refined to some degree, development ceases, as though the builders are completely satisfied for all time with that particular product.

These are hard facts; there are no new departures on the BSA Lightning for ’68. Nevertheless, that peculiar aura remains. This is evident when a 17-year-old service station attendant, overwhelmed by the red and chromium sight, the burbling and chattering sound, blurts in all candor, “I’ve always wanted a BSA like that.” That’s romance.

BSA

650 LIGHTNING

$1375

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE