THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

A recent meeting in San Francisco seemed to sum up everything that is, and has been, wrong with the motorcyclist approach to safety legislation.

An organization, the International Sport Cycle Foundation, issued invitations for “major members of the motorcycle industry” to meet California Assemblyman John Foran, author of a proposed motorcycle safety bill (AB 978) that died in committee at the close of the 1966 session of the California State Legislature. So far, so good. The idea of meeting with the legislator who is chairman of the California Assembly Transportation Committee seemed worthwhile. To engage this influential state assemblyman in intelligent discussion appeared the proper course, as Foran is engaged in preparing a new draft of the proposed motorcycle safety bill, which in all probability will be dropped into the California legislative hopper at the forthcoming session. Great.

All motorcycle dealers in California were invited to attend this meeting — more than 300. Who showed up? There were in attendance representatives of the motorcycle industry, primarily San Francisco Bay area dealers and distributors, a smattering of accessory and helmet manufacturers representatives, a couple of club men, and journalists from the motorcycling press. Here’s where things started to go wrong. Not more than 40 individuals were seated in a room set for 300 when the meeting was opened at the appointed 1 p.m.

Ted Long, director of the International Sport Cycle Foundation, which is headquartered in San Francisco, took the floor. Instead of Assemblyman Foran’s comments, those gathered heard a lengthy pitch for the ISCF, for "what the Foundation can do for the industry.” The essence of Long’s spiel was that, in exchange for unspecified remuneration, the ISCF would establish a lobby in Sacramento to plead the motorcycle industry case to state senators and assemblymen, bureau chiefs, and others directly and indirectly concerned with the motorcycle industry. This pitch somehow seemed far out of place; history shows that lobbyists are secured from within an industry by an organization of that particular industry; rarely, if ever, has the potential lobbyist been forced to plead his case with the industry he desires to represent to government officialdom. The pitch endured for approximately one hour. "You need someone who can call up the right guy and take him to lunch,” or “You need people who know who to talk to.” The initial hour developed no concrete position, or scrap of information, that could be presented to Foran.

Long called a break; shortly, Assemblyman Foran and State Senator Milton Marx appeared, and the meeting was reconvened.

Foran said bluntly, “I'm not a motorcycle driver. I'm an attorney.” He explained that the ill-fated motorcycle safety bill was a hodge-podge of recommendations from highway patrol people, motor vehicle bureau officials, traffic safety engineers and other “safety-minded” individuals. These people, Foran said, agreed “that something should be done about motorcycle safety.” The absence of motorcyclists from the list was quite apparent.

Foran said the group was unanimous in its recommendation to make the wearing of helmets mandatory for Golden State motorcyclists; was unanimous in that special training, licensing and examination procedures be adopted for these motorcyclists; and that face shields, goggles or other forms of protection be made mandatory. Individual viewpoints differed on mandatory crashbars, protective footwear, and special clothing sections of the proposed law. These latter provisions are ones on which the bill foundered in committee.

Foran, obviously a sincere man, concerned about the motorcycle accident rate in his state, admitted his original bill carried ill-advised sections, was cloudy in parts, and generally not the best safety bill that could be produced.

Foran stated flatly, however, that there are a number of good reasons why a motorcycle safety measure soon will be enacted into law in California — 35 million reasons, each worth exactly $1 in federal funds for further construction on interstate highways.

Under the federal highway safety act, states which fail to enact motorcycle (and automobile) safety measures will become ineligible for federal aid for highway construction.

Thus, Foran said, “It is inevitable that we in California have a motorcycle safety law.” The new bill, he said, when reintroduced, probably will be adopted with mandatory wearing of helmets provisions, requirements for protective equipment for riders eyes, and special requirements for motorcycle rider education/examination and licensing.

Though CYCLE WORLD maintains that government should not have the power to dictate what individuals shall wear while riding motorcycles, the staff and management of this magazine believe that when Foran pointed out the inevitability of motorcycle safety legislation for Californians, the representatives of the motorcycle industry should have responded with something like; "Okay, so helmets are inevitable. Let’s do everything we can to insure that the proposed helmet legislation sets forth standards for safe helmets. Let’s work together to make sure there are truly adequate rider education programs for instruction of California youngsters. Let’s see that shatter and penetration standards are set correctly for goggles and face shields,” and on and on. If the motorcycle industry can't fight ’em, it isn’t necessary to join ’em, but the industry can bend its efforts to insure that legislation will be beneficial, not a hindrance to motorcyclists.

What happened? The quick-draw artists of the motorcycle industry slapped leather — and both guns misfired in the shoot-out.

One voice said, “We don't want this legislation.” Everyone realizes that, Assemblyman Foran more clearly than most. From another august industry representative, “It’s not constitutional.” So much for the bother of all the old, windy blasts that should have expired and been discarded years ago.

One proposal was that the wearing of helmets be made permissive, that the helmet should be carried on the machine at all times, but that the placing of it upon the head of the rider be a totally discretionary matter. Hooooooboy! (He was perfectly legal. He had the helmet in his lap when his head hit the fire hydrant.) Use of common sense should determine just how many state lawmakers will buy that.

The meeting closed.

CYCLE WORLD departed with a feeling of deep disappointment. Here had been a chance for the men in the motorcycle industry, the people who really count, to meet in open discussion with the man who will draft the law. The industry had the chance all right — and blew it.

Who blew it? First, there was the individual who pitched so hard for establishment of a motorcycle industry lobby, still another organization. Then there were the 300 individuals whose business is to be deeply affected by whatever the state legislature does. Lastly, there were the men who could have spoken cogently to the topic at hand, yet resorted to tired fatuosity and diatribes against real or fancied abridgement of personal freedoms.

CYCLE WORLD has attended but this one meeting in the one state of 50. This single meeting provided insight into what has happened across the U. S., in the 40-odd states which now carry on their statute books strong motorcycle “safety” legislation — mandatory helmets, crashbars, the whole bag.

Obviously, the motorcycle clan’s own apathy, inattention to important matters, and hewing to 19th century attitudes, have paid off in the legal pitfall in which members of the industry, and the all important individual riders, now find themselves.

There is no quick, sure way out of this tangle. There was 10 years ago. What to do now?

Nationwide, motorcyclists require fewer fragmentary organizations, small-group lobbys, but desperately need strong voices with hearty organizational backing. The Motorcycle, Scooter & Allied Trades Association is one organization that could develop a stronger voice. Many people in the industry complain of an apparent lack of action on the part of MS&ATA. These complaints mainly are that MS&ATA shows little concern in regard to pending legislation in the various states, and that MS&ATA people appear to be doing nothing. MS&ATA is the only body that does have financial support from industry, yet the funds contributed by industry are insufficient to generate a concerted effort in any direction. MS&ATA operates on an annual budget of $100,000. Divide this amount by 50, and there’s the figure of $2000 per state to investigate, lobby and influence officials — a mere pittance, a do-nothing amount. On the basis of past performance, the industry isn’t willing to contribute additional funds. Riders who will be forced to buy a $40 helmet would the AMA, provided that the special items were universally available for purchase.

(Continued on page 50)

This amendment, which could conceivably have led to virtually FIM-tvpe Grand Prix road racers appearing in AMA meets, failed when it went to the vote.

Efforts to allow over 250-cc machines to run five-speed gearboxes and the 250s to use six-speeders also were defeated.

Some rulings, however, were relaxed. Special forks may be used, for example, provided they are approved by the AMA competition committee. Electrical starting systems, starter shafts and crank gears may be removed and there is to be no limit to crankshaft design or to the firing sequence.

This could lead to manufacturers experimenting with outside flywheels and changeovers from 360-dcgrce to 180-degrec crank throws and vice versa.

Full primary chainguards now are mandatory. TT machines for next season must be fitted with operable brakes at front and rear wheels.

For road racing events, both fuel tanks and tires must be of an approved design and at least one quart of gasoline must be taken on during road race pit stops.

Professional sidecar racing is to be sanctioned on all types of courses, provided the outfits comply with AMA regulations.

The machines must have brakes and make no more than two wheel tracks. This prohibits three-wheeled mini-cars and the like. Capacity limit is to be 1300 cc, but no more than one engine may be used.

If the sidecar frame is not integral with the motorcycle, there must be at least four attachment points and the sidecar must be on the right-hand side. Folding footpegs are required on the side of the machine opposite the sidecar.

Minimum ground clearance for the sidecar is at least 1 in. above the sidecar wheel rim, at its lowest point, with the shock absorbers compressed.

On the point of two tracks only, it was decided that minor frame alterations which lead to one wheel being offset should be allowed, provided that the degree of offset is not more than the width of one wheel. Wheels are to be not less than 16 in. and not more than 19 in. in diameter. The front wheel must be sprung. Steerable sidecar wheels are prohibited and only one wheel may be driven.

Roth pilot and passenger must have completed at least one year in sanctioned events before being allowed to compete as professionals.

The question of co-sanction came in for much discussion after it had been reported that a few AMA clubs have been co-sanctioning or co-sponsoring events with other sanctioning organizations.

In the future, any club co-sanctioning an event will be reported to the Executive Committee of the AMA . . . for appropriate disciplinary action.

This “appropriate disciplinary action” apparently means no additional sanctions for the offending club unless the AMA Competition or Executive committees say otherwise.

Minimum purses for sanctioned events were fixed at the congress. Half-mile dirt track and speedway meets must pay at least $900; one-mile, $2,000; and shorttrack and TT races, $600.

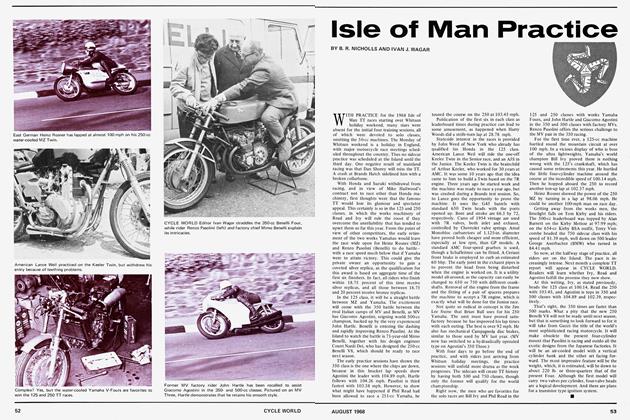

MILLION dollar investments by Japanese and Italian factories will have been wasted and the spectator appeal of World Championship road racing drastically reduced if a recommendation made by the FIM at its recent annual congress eventually goes through.

The recommendation — and remmber the FIM is the body which governs the World Championship series — is that all solo classes, except the 50 cc, should have a maximum of two cylinders, six gears and a minimum weight of 60 kg (132 lb.) dry! This would eliminate all current Championship winning racers — and the FIM wants this to happen as soon as possible.

As a sop to the factories that have supported big-time Grand Prix racing, and spent millions in so doing, the FIM suggests a “Formule Libre” with special events and classifications. Unless this class carries a Championship rating, however, it is unlikely that any of the major factories will lend it support. After all, little publicity benefit is accrued from winning nonChampionship races.

Luckily, the FIM has set no actual date for the recommendation to become a firm ruling . . . but it's the later the better for the majority of people involved in bigtime racing.

No factory racing today really is geared for the production of race-winning, sixspeed twins, so the immediate effect of the new rulings would be to drag International racing back 20 years or so to the point where single-cylinder four-strokes were doing all the winning. No doubt the major factories would develop suitable machines if they thought that sales would benefit from publicity gained in the Championships. On the other hand, they could well believe that, with the diminishing motorcycle market, it would just not be worth all the trouble and expense of developing completely new machines. Then Grand Prix racing, from the point of view of both technical interest and spectacle, would be virtually finished.

One class in Grand Prix racing, however, which does need alteration if it is to survive is the 50-cc class. At the moment it’s a one-horse race with Suzuki running away from a collection of private Hondas, the odd fast Derbi and numerous super slow Italian two-strokes.

A formula now has been drafted which the FIM hopes to put into operation for the 1969 season, and which limits 50-cc Grand Prix racers to one cylinder, six gears, and a minimum dry weight of 60 kg ( 132 lb.).

Though this will make racing much slower, it also will open it to numerous Italian, Spanish. German and Japanese machines, all with a chance to win. The racing will be much closer, thus more exciting and consequently more popular with spectators and organizers.

The FIM agreed that, if posible, the new' formula should be operative for 1969, and certainly no later than 1970.

(Continued on page 69)

It’s the last chance for what has always been a pretty shaky class of Grand Prix racing. If it still doesn’t gain in popularity, don't expect to see Championship 50-cc races in the mid-1970s.

Other FIM recommendations likely to please riders on the Grand Prix circus arc the facts that a certain amount of advertising on machines and clothing is to be allowed and that a minimum scale of expenses for foreign riders in Championship events is to be considered.

The only advertising that will be allowed on machines or clothing must relate to the machine itself, intrinsic parts, or accessories, fuel and lubricants used by it. The ruling applies to all events except the ISDT, and although it still prohibits advertising from outside sponsors, it's a step in the right direction. Perhaps it could entice some support once more from oil companies such BP, which withdrew from racing at the end of the 1967 season.

More good news — especially for spectators — is that all 1968 Championship series events must include at least four classes. And, as soon as the revised regulations for the 50-cc class are finalized, the FIM will insist that at least five classes be included in each meeting.

Private riders also will benefit from this ruling. In the past, many of them have found they were forced to travel several hundreds of miles to ride in just one race. At the Finnish Grand Prix, for example, there is no 350-cc class. Thus many of the British privateers, who usually run a pair of Manx Nortons or an AJS 7R and Matchless G50 in 350-cc and 500-cc classes, went all the w'ay to Finland just for the 500-cc event. Riders such as John Cooper and Rod Gould were chasing C hampionship points after leader board placings in the East German and Czechoslovakian Grands Prix, and simply could not afford to pass up a 500-cc ride in Finland. The journey from England involved a great deal of driving and two lengthy boat trips, so that the starting money paid by the Finnish organizers for a single race just about covered their expenses.

The extra starting money for a 350 ride, for example, would have made the difference between merely breaking even and making a profit — which, after all. is what motivates professional riders to race. ■