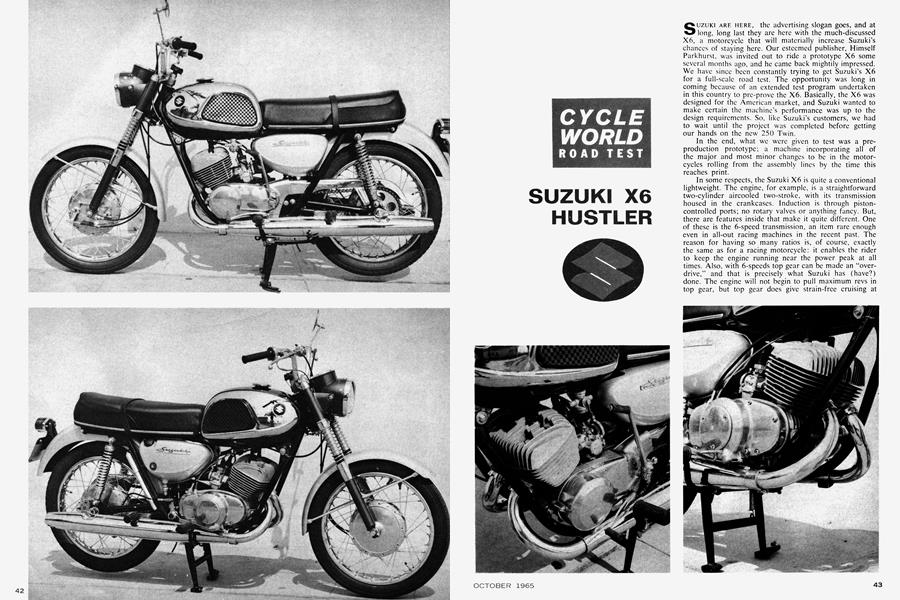

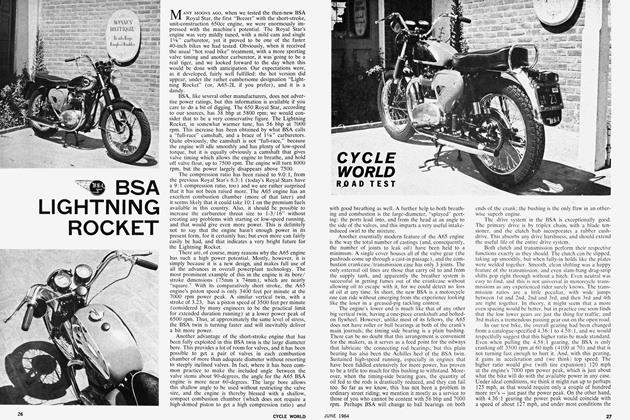

SUZUKI X6 HUSTLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

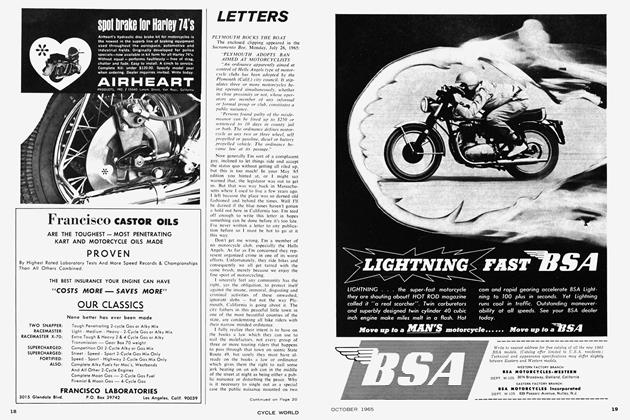

SUZUKI ARE HERE, the advertising slogan goes, and at long, long last they are here with the much-discussed X6, a motorcycle that will materially increase Suzuki’s chances of staying here. Our esteemed publisher, Himself Parkhurst, was invited out to ride a prototype X6 some several months ago, and he came back mightily impressed. We have since been constantly trying to get Suzuki’s X6 for a full-scale road test. The opportunity was long in coming because of an extended test program undertaken in this country to pre-prove the X6. Basically, the X6 was designed for the American market, and Suzuki wanted to make certain the machine’s performance was up to the design requirements. So. like Suzuki’s customers, we had to wait until the project was completed before getting our hands on the new 250 Twin.

In the end, what we were given to test was a preproduction prototype; a machine incorporating all of the major and most minor changes to be in the motorcycles rolling from the assembly lines by the time this reaches print.

In some respects, the Suzuki X6 is quite a conventional lightweight. The engine, for example, is a straightforward two-cylinder aircooled two-stroke, with its transmission housed in the crankcases. Induction is through pistoncontrolled ports; no rotary valves or anything fancy. But, there are features inside that make it quite different. One of these is the 6-speed transmission, an item rare enough even in all-out racing machines in the recent past. The reason for having so many ratios is, of course, exactly the same as for a racing motorcycle: it enables the rider to keep the engine running near the power peak at all times. Also, with 6-speeds top gear can be made an “overdrive,” and that is precisely what Suzuki has (have?) done. The engine will not begin to pull maximum revs in top gear, but top gear does give strain-free cruising at 70 mph and that is the object of having an overdrive.

With so many ratios, the transmission gear cluster is rather wide, but the shafts are fairly large in diameter and no problems with flexing should occur. These shafts run in ball and roller bearings; there are no plain bushings except between the gears and the shafts. The gears are in constant mesh and engagement is made through facedogs. All ratios are indirect, as the power comes in on one shaft and passes across pairs of gears to the other, which carries the “countershaft” sprocket. The shifting forks are operated from cam-slots in a rotating drum. This drum is somewhat larger in diameter than is normal, because all such drums must do their work in less than a full revolution and the more ratios that are involved, the “steeper” the cam slots must be. increasing the drum diameter has the effect of reducing cam-slot steepness and that, in turn, makes the shift action smoother and more positive.

One point we should make for the benefit of all potential X6 buyers is that in any situation that requires the use of 5th, or even 4th gear, instead of 6th, you may use the lower gear without fear of damaging anything. All gears arc indirect, and the transmission is indifferent to which pair of its gears are transmitting power. Wear, and friction losses will be the same. When a transmission has a “direct” top gear, the power has to make a double detour in all other gears, and this has developed in all of us a tendency to get into top as soon as possible. Forget it. When riding the X6, use whatever gear is needed to keep the engine “on the boil.”

In keeping with what must soon become universal practice for two-stroke motorcycle engines, the X6 is outfitted with an automatic-oiling system. This is not exactly new; we tested a 250cc Puch that featured automatic oiling in February, 1963. However, the feature that separates the Suzuki X6 from other two-strokes with automatic oiling is the manner in which the oil is fed into the engine. Oil from the Suzuki's engine-driven pump is fed through a pair of plastic lines to “banjo” fittings on the top of the crankcase, and from there drilled passages direct the oil to the outboard mainbearings. After lubricating these bearings, the oil is thrown from the spinning bearing race and is promptly captured in the rim by a pressed-metal dish fixed to the outboard crank flywheels. A hole in this dish admits the oil to the hollow-bored crankpin and a small hole drilled through the crankpin wall feeds the oil to the crankpin bearings. Finally, the oil is thrown from the crankpin to the cylinder walls to lubricate them and ultimately to be burned and disappear down the exhaust pipes.

You will note that we have not, as yet, made any mention of lubricating the center mainbearing. This function is assumed by the transmission oil. Oil being tossed about by the churning transmission gears is collected in one side of a U-shaped trap, and overflows from the other side of the trap to spill into the bearing. A drain returns the oil to the transmission sump after it has done its work. The purpose of the U-shaped trap is to collect any bits of grit in the oil and prevent them from damaging the crankshaft's center mainbearing. And, too, we may assume that in the course of several hundred miles of riding, this trap would tend to gather up most of the particles in the oil and thus serve as a filter. The trap may be cleaned by removing a drain-plug from the bottom of the trap, this being exposed under the sump.

The lubricating pump is driven by the engine, but in a very indirect fashion. This Suzuki twin-cylinder engine has a helical-gear primary drive, and a small-diameter spur gear on the back of the clutch hub drives a pair of spur gears leading back to the rear of the transmission casing. The last gear in this train serves a triple purpose: first, it takes the drive to the lubricating pump; second, it provides a drive for the tachometer; and finally, it is part of the kickstart drive mechanism. We might mention here that this arrangement keeps both tachometer and oil pump in operation even when the clutch is disengaged, and that it allows the rider to start the engine even when the transmission is in gear by simply pulling the clutch lever.

The pump output is obviously closely related to engine speed, as it is engine-driven, but there is an over-riding control to vary output according to throttle opening. An engine running at reduced throttle is not working hard, and does not need as much oil as when full throttle is applied. The pump piston is rotated by a form ot worm drive, and its reciprocating motion comes from a cam ground at one end which runs against a peg. An adjustable travel-stop shortens the stroke of the pump as the throttle is closed. Holes drilled in the pump-piston valve oil in and out through ports in the pump body as the piston rotates. We have no figures on the oil delivery rate, but this must be quite low even at full throttle, for the exhausts show little smoke at any time, and a single tank of oil seems to last forever. Very probably, an exceedingly small flow of oil is all that is required. All of the oil goes directly to the bearings and that would tend to minimize the total amount of oil required. A glass “peep-hole” is provided in the side of the oil tank to show when the oil is getting low. There is also a sediment trap on the oil tank where the feed-line emerges, to keep particles out of the pump and delivery lines. This is important, for the banjo fittings on the crankcase incorporate a check valve to keep crankcase pressure from blowing the oil back through the lines. Even very small pieces of grit could hold one or both of the check-balls off the seat and that would seriously reduce the flow of oil to the bearings. Interestingly enough, the fuel tank also has a sediment trap, and"a level “glass”. This last is a small plastic tube tucked away at the front of the tank, and you can see how much fuel is in the tank just by looking at the level in the tube. A very simple and effective fuel “gauge.” The fuel filler cap is simple and effective too, being a rubber cork with a chromed metal cover. The oil tank has a screw-on cap.

One feature of the Suzuki's engine/transmission unit everyone will like but most people will overlook on first acquaintance is the fact that the main cases are split along a horizontal line. This means that you can expose everything for easy adjustment or replacement simply by flipping the unit over and removing the bottom half of the cases. No need for pullers to coax bearings from holes in which they have been pressed.

Other miscellaneous good features on the engine/ transmission are such things as the aluminum cylinders, which are lighter and cool more efficiently than the usual iron cylinders. These cylinders have a cast-in iron liner, and someone has calculated expansion rates very nicely for it is very difficult to seize this engine. We put the bike to the test by running flat-out for long periods in extremely warm weather carrying two-up and there was not a hint of tightening.

Our test machine had its shift lever on the left side but the regular production-line version will have its shifter shaft going straight through the die-cast alloy cases with an exposed, serrated end on each side. The buyer will thus be able to place the shift lever on the left or right side (moving the brake as well) to suit his own preference. We hope at the same time the makers will provide a slightly longer gear lever; the lever on our test bike was a bit too short for the average (big) American fpot.

Most of the noise from any moderately well-muffled two-stroke comes from the carburetors. Suzuki's X6 not only has very effective exhaust mufflers, but the aircleaner incorporates a silencer to quiet the induction gasp. It works, too. You can use a lot of throttle on the X6 and cause very little commotion — except, of course, that a lot of throttle makes the X6 go down the road so fast. The mufflers are, by the way, mounted quite high and in close, and the bike can be cornered with considerable elan before anything drags.

For once, we have a bike without folding passenger pegs that we cannot object to very strenuously. The Suzuki’s rear pegs are rigid, but you cannot hang your leg on them too easily as they are also short, and tucked in right above the mufflers. These, and the pegs for the rider, are well placed. We are told that the placement of the pegs was one of the most difficult tasks in refining the X6 for America’s riders. It seems that we have a lot of variation in size here, and there was a lot of juggling back and forth before a location was found that suited

a maximum percentage of riders.

Similar development agonies attended the selection of handlebars and seat, but we would say that the time was well spent. The X6 has a comfortable riding position, and it suited everyone on our staff — which covers quite a wide range in physical dimensions. The scat is long enough to accommodate two in reasonable comfort, but when a passenger is carried, the rider will be obliged to slide forward onto the narrowed front of the seat. This is not bad for the first hour of riding, but for periods longer than that, a bit more width would be appreciated.

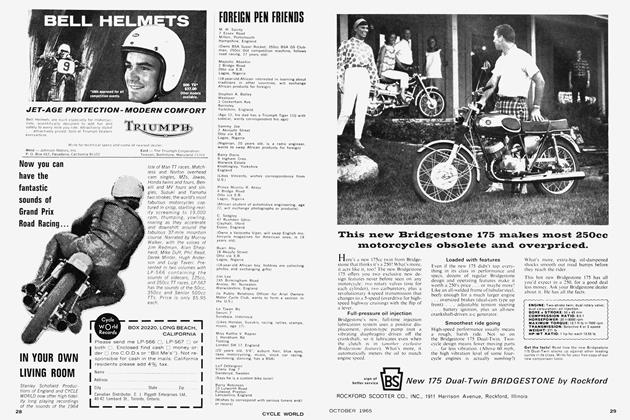

Handling is exceptionally good. The X6 has a frame and suspension that show a strong family resemblance to Suzuki’s road racing motorcycles, not only in appearance, but in results as well. The bike's springing is slightly more firm than most touring machines, but it is our opinion that whatever has been lost in terms of a soft, floating ride is more than compensated by the way the X6 goes around corners. We tried two of these new Suzuki twins, and both handled very well. One (the bike with which we obtained our performance figures) had a friction-type steering damper; the other was fitted with a hydraulic damper, bolted-on at the lower end of the steering stem. This is not the usual type of damper, with a piston inside a cylinder hanging between the forks and the frame. Instead, it is a small drum, probably containing fixed and moving vanes. Like the old-style lever-acting “shockabsorbers” used on automobiles but without the lever. The people in the know at Suzuki tell us that this hydraulic damper will be a standard item on the production-line X6. Presumably, so will the steering-lock we noticed on our test bike.

A lot of attention has been given to making the X6 stop, as well as go. The machine is fitted with brakes of no more than moderate size (7-inch diameter) but they do the job very' well indeed. Of course, the drums are of aluminum, and there is double-leading actuation for the front shoes, but these things on at least one other motorcycle have not provided very exceptional braking. The Suzuki obviously also has enough thickness in the drums, and their iron liners, and the right material in the brake linings, to make the brakes work well. Hard use on curving, downhill mountain roads failed to reveal any deficiency.

We also liked the fact that the rear brake was cableoperated, an almost universal arrangement these days, and that there were dust covers at the cable ends to exclude road grit. Wheel-type adjusters, for wear-compensation, are provided at the handlebar levers (one is for the clutch) and also down at the brake cam levers. This is one motorcycle that will allow you to take up slack until the linings are gone and the shoes have half-disappeared.

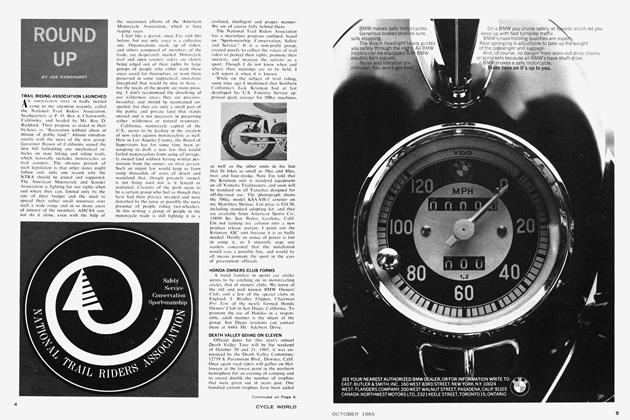

If one counts the level gauges on the fuel and oil tanks, the Suzuki’s instrumentation is a lot more elaborate than is usual for motorcycles. There is even a high-beam indicator light. And the combined speedomctcr/tachometer cluster, with the former reading to 120 mph; the latter to 9000 rpm. The normal red-line is at 8000 rpm, but there is a printed overlay on the glass covering the tachometer that shows a 4000 rpm limit for the first 500 miles, and a 5000 rpm limit up to 1000 miles. After that break-in period you simply wipe away the overlay and use the 8000 rpm limit shown on the tach’s face. A clever touch here is the use of a white needle on the specdo dial, and yellow for the tach. Being grouped together on the same instrument face, there is some tendency to confuse the two at first glance, and the color-coding helps one’s eye find the right dial quickly.

Regular production versions of the Suzuki X6 wiil have the prototype's general form and finish, but the fenders will be striped, and the battery' and tool-case covers will be painted to match the fuel tank. We arc told, too, that their crankshafts will have a slightly different balance factor, to correct for a somewhat excessive vibration we noted in the prototypes.

With or without any changes, if the normal production version is as fast as our prototype test bike (Suzuki says it will be faster) it will be well worth having. At this writing, the X6 is the fastest touring-type 250 we have ever tested. Almost anyone of average weight can get on the X6 and crack off an 80 mph standing-start quarter, and our regular test rider had a best run very near 85 mph, and the 84 mph shown in the performance data page can be considered a realistic average; ditto for the 15.3second elapsed time. A Suzuki employee, Yosho Itoh, who attended our drag-strip session did slightly better; but then he only weighs about 95 pounds, sopping wet.

A rather snappish clutch presents the only problem in getting very fast drag-strip times with the X6. Once the bike is underway (and after one masters the clutch it gets away very smartly) the rider simply runs to 9000 rpm in each gear and then bangs into the next higher gear. But, if it was necessary to take the time from neutral, and all the way through to 6th gear, some problems might arise. We found that while it was easy to find neutral, dropping into 1st required close attention. At times, when the lever wras pressed, the first “click” did not mean that 1st had been engaged, so we had to be doubly sure by hitting the lever twice. And, curiously enough, there was an even more pronounced double-notch going into 6th.

Still, and even in the face of all those missed shifts, we were most favorably impressed with the X6. The handling was especially good and the performance phenomenal. Moreover, it is one of the few 250-class motorcycles that will pack double without feeling as though the front wheel is poised about an inch above the road. And, even though it is obviously rather highly tuned, it was invariably a first-kick starter for us. We are told that the price will be about $650. Suzuki are (is?) going to sell a whole passie of them. •

SUZUKI

X-6 HUSTLER

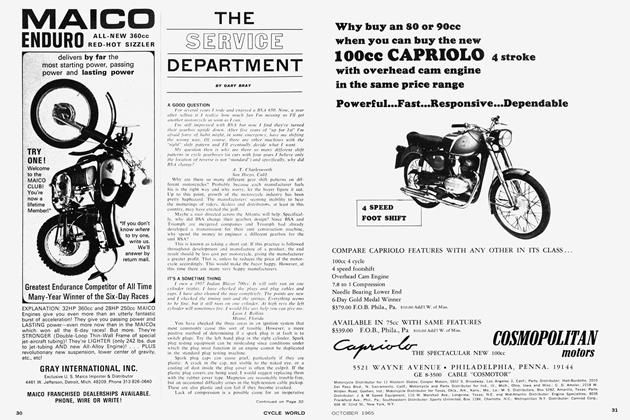

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE