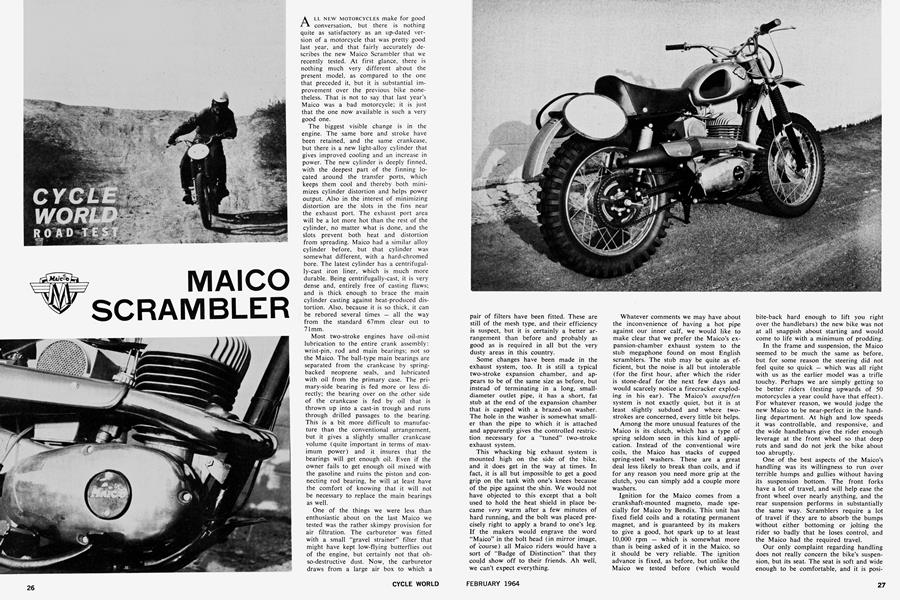

MAICO SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

ALL NEW MOTORCYCLES make for good conversation, but there is nothing quite as satisfactory as an up-dated version of a motorcycle that was pretty good last year, and that fairly accurately describes the new Maico Scrambler that we recently tested. At first glance, there is nothing much very different about the present model, as compared to the one that preceded it, but it is substantial improvement over the previous bike nonetheless. That is not to say that last year's Maico was a bad motorcycle; it is just that the one now available is such a very good one.

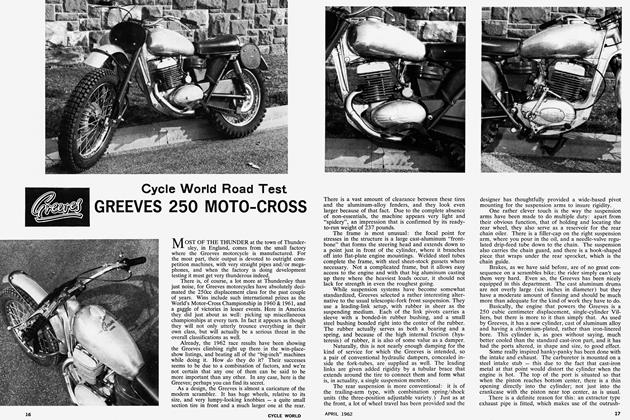

The biggest visible change is in the engine. The same bore and stroke have been retained, and the same crankcase, but there is a new light-alloy cylinder that gives improved cooling and an increase in power. The new cylinder is deeply finned, with the deepest part of the finning located around the transfer ports, which keeps them cool and thereby both minimizes cylinder distortion and helps power output. Also in the interest of minimizing distortion are the slots in the fins near the exhaust port. The exhaust port area will be a lot more hot than the rest of the cylinder, no matter what is done, and the slots prevent both heat and distortion from spreading. Maico had a similar alloy cylinder before, but that cylinder was somewhat different, with a hard-chromed bore. The latest cylinder has a centrifugally-cast iron liner, which is much more durable. Being centrifugally-cast, it is very dense and, entirely free of casting flaws; and is thick enough to brace the main cylinder casting against heat-produced distortion. Also, because it is so thick, it can be rebored several times — all the way from the standard 67mm clear out to 71 mm.

Most two-stroke engines have oil-mist lubrication to the entire crank assembly: wrist-pin, rod and main bearings; not so the Maico. The ball-type main bearings are separated from the crankcase by springbacked neoprene seals, and lubricated with oil from the primary case. The primary-side bearing is fed more or less directly; the bearing over on the other side of the crankcase is fed by oil that is thrown up into a cast-in trough and runs through drilled passages to the bearing. This is a bit more difficult to manufacture than the conventional arrangement, but it gives a slightly smaller crankcase volume (quite important in terms of maximum power) and it insures that the bearings will get enough oil. Even if the owner fails to get enough oil mixed with the gasoline and ruins the piston and connecting rod bearing, he will at least have the comfort of knowing that it will not be necessary to replace the main bearings as well.

One of the things we were less than enthusiastic about on the last Maico we tested was the rather skimpy provision for air filtration. The carburetor was fitted with a small "gravel strainer" filter that might have kept low-flying butterflies out of the engine, but certainly not that ohso-destructive dust. Now, the carburetor draws from a large air box to which a pair of filters have been fitted. These are still of the mesh type, and their efficiency is suspect, but it is certainly a better arrangement than before and probably as good as is required in all but the very dusty areas in this country.

Some changes have been made in the exhaust system, too. It is still a typical two-stroke expansion chamber, and appears to be of the same size as before, but instead of terminating in a long, smalldiameter outlet pipe, it has a short, fat stub at the end of the expansion chamber that is capped with a brazed-on washer. The hole in the washer is somewhat smaller than the pipe to which it is attached and apparently gives the controlled restriction necessary for a "tuned" two-stroke exhaust system.

This whacking big exhaust system is mounted high on the side of the bike, and it does get in the way at times. In fact, it is all but impossible to get a good grip on the tank with one's knees because of the pipe against the shin. We would not have objected to this except that a bolt used to hold the heat shield in place became very warm after a few minutes of hard running, and the bolt was placed precisely right to apply a brand to one's leg. If the makers would engrave the word "Maico" in the bolt head (in mirror image, of course) all Maico riders would have a sort of "Badge of Distinction" that they could show off to their friends. Ah well, we can't expect everything.

Whatever comments we may have about the inconvenience of having a hot pipe against our inner calf, we would like to make clear that we prefer the Maico's expansion-chamber exhaust system to the stub megaphone found on most English scramblers. The stub may be quite as efficient, but the noise is all but intolerable (for the first hour, after which the rider is stone-deaf for the next few days and would scarcely notice a firecracker exploding in his ear). The Maico's auspuffen system is not exactly quiet, but it is at least slightly subdued and where twostrokes are concerned, every little bit helps.

Among the more unusual features of the Maico is its clutch, which has a type of spring seldom seen in this kind of application. Instead of the conventional wire coils, the Maico has stacks of cupped spring-steel washers. These are a great deal less likely to break than coils, and if for any reason you need more grip at the clutch, you can simply add a couple more washers.

Ignition for the Maico comes from a crankshaft-mounted magneto, made specially for Maico by Bendix. This unit has fixed field coils and a rotating permanent magnet, and is guaranteed by its makers to give a good, hot spark up to at least 10,000 rpm — which is somewhat more than is being asked of it in the Maico, so it should be very reliable. The ignition advance is fixed, as before, but unlike the Maico we tested before (which would bite-back hard enough to lift you right over the handlebars) the new bike was not at all snappish about starting and would come to life with a minimum of prodding.

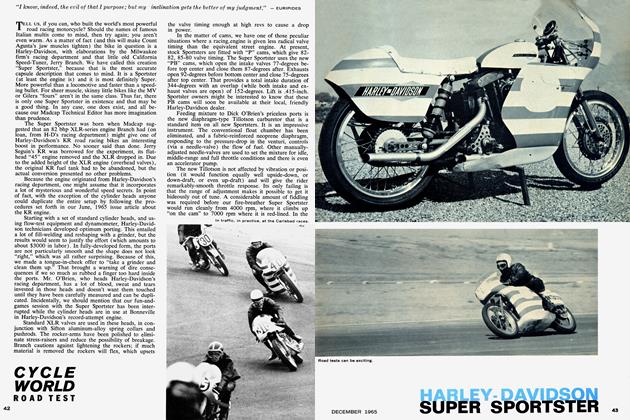

In the frame and suspension, the Maico seemed to be much the same as before, but for some reason the steering did not feel quite so quick — which was all right with us as the earlier model was a trifle touchy. Perhaps we are simply getting to be better riders (testing upwards of 50 motorcycles a year could have that effect). For whatever reason, we would judge the new Maico to be near-perfect in the handling department. At high and low speeds it was controllable, and responsive, and the wide handlebars give the rider enough leverage at the front wheel so that deep ruts and sand do not jerk the bike about too abruptly.

One of the best aspects of the Maico's handling was its willingness to run over terrible humps and gullies without having its suspension bottom. The front forks have a lot of travel, and will help ease the front wheel over nearly anything, and the rear suspension performs in substantially the same way. Scramblers require a lot of travel if they are to absorb the bumps without either bottoming or jolting the rider so badly that he loses control, and the Maico had the required travel.

Our only complaint regarding handling does not really concern the bike's suspension, but its seat. The seat is soft and wide enough to be comfortable, and it is positioned well enough for a short rider. The tall boys will have their problems with it, however. Stand up on the pegs for a fast charge through the badlands and then bounce your hindside back and down for traction in sand and you will find that it has almost missed the back of the seat and hit the fender. And, the seat slopes forward so much that even if you don't happen to care for the belly-button against-thesteering-crown stance while sliding around corners, you will slip forward into that position anyway. Of course, all of this can be changed quite easily by altering the seat mountings or replacing the seat itself. It is a minor point in any case, and in all likelihood, most riders will approve of the seating just as it is.

The straight-line performance of the Maico, as seen in the acceleration graph, does not look too impressive, but that is somewhat misleading. The bike, as tested, was geared more for speed than acceleration, and it would appear much better if fitted with sprockets that would allow the engine to peak at the end of the 1/4-mile mark. In point of fact, the Maico impressed us as being exceptionally powerful for a 250, and capable of making a creditable showing in any of the local hotlycontested high-speed scrambles — which are more like TT or flattrack event (with a lot of humps and curves thrown in) than the classic sand-and-mud events.

Least important of all the improvements (from the standpoint of function), but highly pleasing for all that, was that made in overall finish. We had some rather harsh things to say about this aspect of the previous Maico, which abounded with rough edges and hastily-applied paint, but none of them apply to the model we just tested. The standard of workmanship on the new machine is quite high, and would stand comparison with any other bike made for the same purpose and selling for roughly the same price. •

MAICO 250 SCRAMBLER

SPECIFICATIONS

$795.00