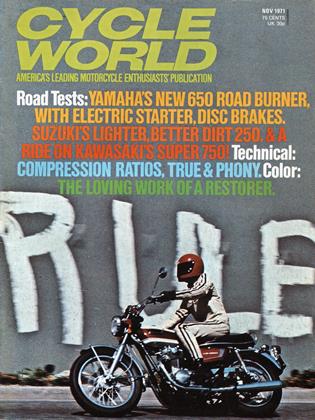

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

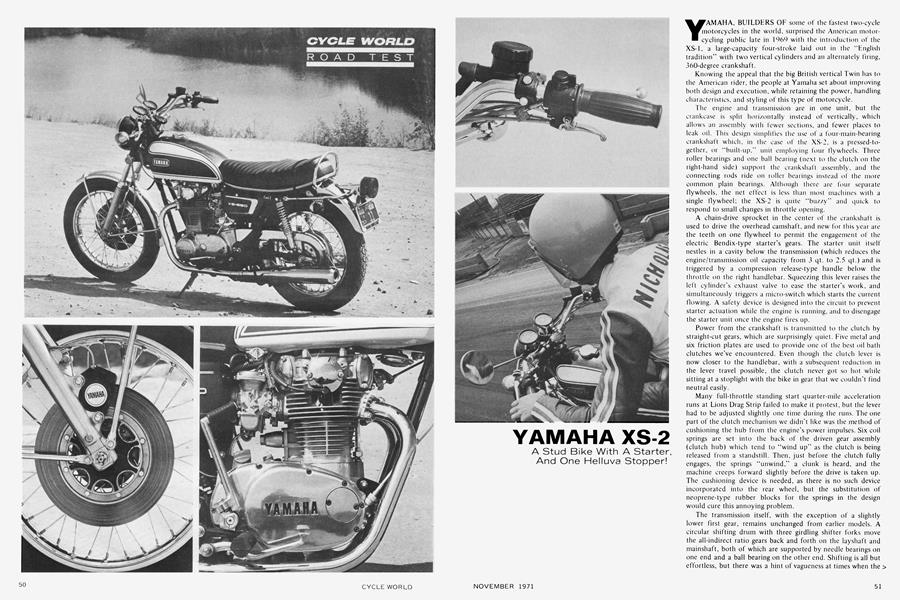

YAMAHA XS-2

A Stud Bike With A Starter, And One Helluva Stopper!

YAMAHA, BUILDERS OF some ot the fastest two-cycle motorcycles in the world. surprised the American motorcycling public late in 1969 with the introduction of the XS-1, a large-capacity tour-stroke laid out in the "English tradition" with two vertical cylinders and an alternately firing, 360-degree crankshaft.

Knowing the appeal that the big British vertical Twin has to the American rider, the people at Yamaha set about improving both design and execution, while retaining the power, handling characteristics, and styling of this type of motorcycle.

The engine and transmission are in one unit, but the crankcase is split horizontally instead of vertically, which allows an assembly with fewer sections, and fewer places to leak oil. This design simplifies the use of a four-main-bearing crankshaft which, in the case of the XS-2, is a pressed-together, or “built-up,” unit employing four flywheels. Three roller bearings and one ball bearing (next to the clutch on the right-hand side) support the crankshaft assembly, and the connecting rods ride on roller bearings instead of the more common plain bearings. Although there arc four separate flywheels, the net effect is less than most machines with a single flywheel; the XS-2 is quite “huzzy” and quick to respond to small changes in throttle opening.

A chain-drive sprocket in the center of the crankshaft is used to drive the overhead camshaft, and new for this year are the teeth on one flywheel to permit the engagement of the electric Bendix-type starter’s gears. The starter unit itself nestles in a cavity below the transmission (which reduces the engine/transmission oil capacity from 3 qt. to 2.5 qt.) and is triggered by a compression release-type handle below the throttle on the right handlebar. Squeezing this lever raises the left cylinder’s exhaust valve to ease the starter’s work, and simultaneously triggers a micro-switch which starts the current flowing. A safety device is designed into the circuit to prevent starter actuation while the engine is running, and to disengage the starter unit once the engine fires up.

Power from the crankshaft is transmitted to the clutch by straight-cut gears, which are surprisingly quiet. Five metal and six friction plates are used to provide one of the best oil bath clutches we've encountered. Even though the clutch lever is now closer to the handlebar, with a subsequent reduction in the lever travel possible, the clutch never got so hot while sitting at a stoplight with the bike in gear that we couldn’t find neutral easily.

Many full-throttle standing start quarter-mile acceleration runs at Lions Drag Strip failed to make it protest, but the lever had to be adjusted slightly one time during the runs. The one part of the clutch mechanism we didn't like was the method of cushioning the hub from the engine’s power impulses. Six coil springs are set into the back of the driven gear assembly (clutch hub) which tend to “wind up” as the clutch is being released from a standstill. Then, just before the clutch fully engages, the springs “unwind,” a clunk is heard, and the machine creeps forward slightly before the drive is taken up. The cushioning device is needed, as there is no such device incorporated into the rear wheel, but the substitution of neoprene-type rubber blocks for the springs in the design would cure this annoying problem.

The transmission itself, with the exception of a slightly lower first gear, remains unchanged from earlier models. A circular shifting drum with three girdling shifter forks move the all-indirect ratio gears back and forth on the layshaft and mainshaft, both of which are supported by needle bearings on one end and a ball bearing on the other end. Shifting is all but effortless, but there was a hint of vagueness at times when the engine was hot. The closeness of the gear ratios makes the bike seem more like a road racer than a roadster, and the engine's smooth, broad power band makes the five speeds seem almost superfluous.

Continuing upward, the three-ring (two compression and one oil con trol ring) pistons run on bushings at the top of the connecting rods, as opposed to the needle bearings found in earlier models. A cast iron sleeve is located in the finned aluminum cylinder casting on either side of a tunnel for the camshalt chain. At the rear is the cam chain tensioner wheel and adjustment screw, and a long, rubber-faced chain damper assembly is placed in the front of the cylinder casting. A total of eight hold-down studs secure the cylinder and head to the crankcase.

I he cylinder head is a smooth aluminum alloy casting with moderately shallow combustion chambers, straight-in inlet ports and slightly splayed exhaust ports to promote better cylinder head cooling. Double coil valve springs close the valves, and valve guide seals are provided to prevent oil from being used excessively. The intake balance tube between the inlet ports has disappeared.

I he hollow camshaft is supported by two ball bearings on each side, and its lett and right ends are used to drive the ignition contact points and the spark advance mechanism. A detachable rocker box houses four separate rocker shafts, each with a linger-type cam follower. Valve clearance adjustment is accomplished through three triangular and one roughly square (at the left exhaust valve position) leak-proof covers.

Oil tor the XS-2's internals is circulated by a trochoidal pump which features four inner vanes and five outer vanes. Both rotors turn together, but rotate at different speeds and create a gap between themselves which is filled with oil. Hence, there is an almost smooth flow of lubricant to the crankshaft main and connecting rod bearings, transmission mainshaft, clutch bearing and shifting mechanism. Oil for the rocker arms and valve gear is delivered through a pipe at the front ol the cylinder. “Splash” lubrication is used to lubricate the crankshaft, small end bearings, pistons and cylinder walls, and the primary drive gears. A bypass valve redirects oil around the oil filter and back into the oil reservoir if the pressure becomes too great.

Mikuni “constant velocity” carburetors, manufactured under license from Solex, provide outstanding throttle response and amazing fuel economy, as well as smooth idling. A butterfly valve located downstream of the needle controls the amount of air coming into the front (intake end) of the carburetor. A rubber diaphragm is connected to the top of the slide (piston valve) which divides the top part of the carburetor into a vacuum chamber. An air bleed hole which leads to the underside of the diaphragm admits air at atmospheric pressure to that area, and a hole in the bottom of the slide leads to the top of the vacuum chamber. As the butterfly is opened a vacuum is generated beneath the slide and it rises according to the opening of the butterfly valve. Hence, it is impossible to flood the engine by using the throttle too vigorously, as the slide will rise no higher to admit more fuel/air mixture than the engine can use.

Electrical chores are handled admirably by a crankshaftmounted alternator whose a.c. current is rectified to d.c. by a three-phase, full-wave rectifier. The flow to the battery, as well as a trickle to excite the rotor windings, to promote current production, is controlled by a voltage regulator. A 14-15V d.c. current is kept flowing into the new, larger 12V-12AH battery, which is plenty large enough to drive the electric starter, the main lighting system and the turn signals. Electrical components, of course, are first rate.

Basically unchanged is the double loop, cradle-type frame with a single large toptube running under the gas tank. Ample support is provided tor the engine, which is rigidly mounted in the frame, and liberal gusseting around the steering head and swinging arm pivot offer a true tracking machine. Our first test of the 650-cc Yamaha revealed what felt like a hinge right under the seat when the machine was banked over hard in a corner. However, better rear suspension units and slightly stiffer front suspension with redesigned damping has all but cured this problem. Front fork action is almost too soft for best control at high speeds over rough surfaces, but slightly heavier oil would help the “wallowing” at the expense of a slightly stiffer ride. The footpegs arc set rather low to the ground, and can be grounded without too much trouble when negotiating fast sweepers, but the average rider should have no problems. With so much of the engine’s weight up high, there > is still a feeling of top-heaviness at crawling speed, but this feeling disappears as you accelerate.

YAMAHA XS-2

$1295

A friction-type steering damper is useful when traveling at high speeds, as the front end has a slight tendency to “search” and sets up a slight “wallow” at turnpike speeds. If the damper is left screwed down while riding in town, the machine feels very clumsy. Loosening the damper only a little, however, cures this sensation, and the XS-2 feels almost as nimble as a good 350. A wide, comfortable dual seat used in conjunction with the rather low-mounted footpegs makes long touring very comfortable. Our only exception to the control group is the handlebars, which look as though they came off Keith Mashburn’s flat tracker! They're a bit too far swept back for comfort in the wrist area when seated on the front half of the

seat. Scoot back on the seat and they feel neat, but too far and you’ll have your passenger sitting on the fender! However, they can’t be all bad, as one of our staff riders, whose physique resembles that of a well-fed spider, thought they were just dandy.

The addition of the powerful disc brake to the front wheel is one of the most outstanding improvements made for 1972. The caliper unit is bolted directly to the right-hand fork leg and resists wheel cocking when the brake is applied hard. Only two fingers are necessary to lock the front wheel under any conditions, so caution is the word at first. The brake lever operates the master cylinder directly and features an adjustment screw and lock nut, allowing the rider to vary the point where the brake begins to engage. T his is extremely nice for riders with short fingers or small hands. As is common practice with motorcycle disc brakes, the disc is fabricated out of a stainless steel alloy instead of cast iron. An i ron disc is more effective and somewhat quieter in operation than a stainless compound, but iron rusts rapidly and spoils the appearance of the motorcycle. The Yamaha’s front brake squeals loudly when slowing from moderate speeds, so we hope that quieter brake pads are in the offing. Disc brakes are more expensive than drum brakes, but with so many powerful machines on the road today with less than excellent stopping ability, we expect to see discs on more machines as the year progresses.

The rear brake, which does only a moderate amount of the stopping chore, is a conventional single-leading shoe affair that performs very well and is slow to heat up and fade. No adjustment of the rear brake was necessary during the test, and of course the front brake is self-adjusting.

A few of our other minor complaints against the first XS-1 have been rectified by Yamaha. One of the most vehement of these concerned the vibration occurring throughout the engine’s rpm range over idle speed. Changes made to the crankshaft’s balance factor bave helped out enormously. Rubber-mounted handlebars and footpegs have been employed since the first models to help stifle the vibration, and now the combination really works. Practically no vibration gets past the handlebars, and only a tingle is felt in the footpegs at highway speeds.

Another ot our complaints was the noise made by the megaphone-type mufflers. It was not only loud, but also had a peculiar “nasal” quality about it which was particularly obnoxious to several of our staff members. Happily, Yamaha has made several changes in the baffling arrangement, and the result is an authoritative, yet pleasant, sound. There is almost no mechanical noise from the engine and, as in the past, the unit is almost tree from oil leaks. Changes to washers and seal design have made the XS-2 even more oil tight than before.

Instrumentation is very good, but the speedometer is quite optimistic. A neutral indicator light and turn signal indicator are located in the tachometer face, and the high beam indicator is a red light in the top of the headlight. All thumb-operated controls are well shaped, within easy reach of the handle grips, and the ignition switch is ensconced between the speedometer and tachometer, obviating the need to fumble around under the gas tank.

Power delivery is among the smoothest we’ve sampled on a machine of this engine configuration. Power comes on strong as low as 2000 rpm and continues in a smooth surge well past the 7500-rpm red-line. Several of the ohe Yamahas being used for racing are being spun in excess of 9000 rpm!

The XS-2 is undoubtedly the best buy in a machine of its type. The sum total ot its parts makes it a sporting machine without equal, a stud with a starter, promising great times on the boulevards with few maintenance hassles. [Ö]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpLess Sound More Ground

November 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1971 -

Departments:

Departments:"Feedback"

November 1971 -

Departments:

Departments:The Service Dept

November 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

...Elsewhere On the Preview Circuit

...Elsewhere On the Preview CircuitHarley-Davidson Lays It On

November 1971