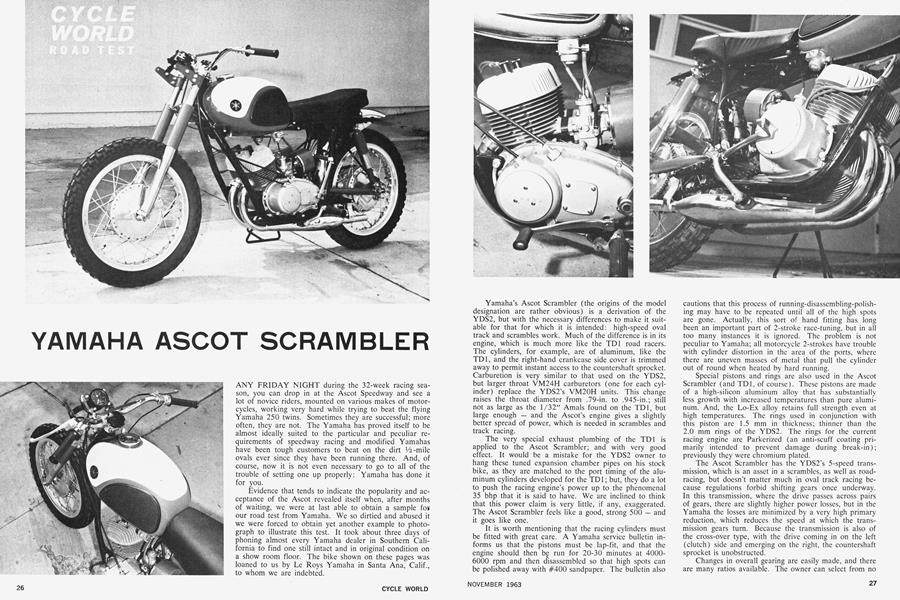

YAMAHA ASCOT SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

ANY FRIDAY NIGHT during the 32-week racing season, you can drop in at the Ascot Speedway and see a lot of novice riders, mounted on various makes of motorcycles, working very hard while trying to beat the flying Yamaha 250 twins. Sometimes they are successful; more often, they are not. The Yamaha has proved itself to be almost ideally suited to the particular and peculiar requirements of speedway racing and modified Yamahas have been tough customers to beat on the dirt Vi-mile ovals ever since they have been running there. And, of course, now it is not even necessary to go to all of the trouble of setting one up properly: Yamaha has done it for you.

Evidence that tends to indicate the popularity and acceptance of the Ascot revealed itself when, after months of waiting, we were at last able to obtain a sample foi our road test from Yamaha. We so dirtied and abused it we were forced to obtain yet another example to photograph to illustrate this test. It took about three days of phoning almost every Yamaha dealer in Southern California to find one still intact and in original condition on a show room floor. The bike shown on these pages was loaned to us by Le Roys Yamaha in Santa Ana, Calif., to whom we are indebted.

Yamaha’s Ascot Scrambler (the origins of the model designation are rather obvious) is a derivation of the YDS2, but with the necessary differences to make it suitable for that for which it is intended: high-speed oval track and scrambles work. Much of the difference is in its engine, which is much more like the TD1 road racers. The cylinders, for example, are of aluminum, like the TD1, and the right-hand crankcase side cover is trimmed away to permit instant access to the countershaft sprocket. Carburetion is very similar to that used on the YDS2, but larger throat VM24H carburetors (one for each cylinder) replace the YDS2’s VM20H units. This change raises the throat diameter from .79-in. to .945-in.; still not as large as the 1/32" Amals found on the TD1, but large enough — and the Ascot’s engine gives a slightly better spread of power, which is needed in scrambles and track racing.

The very special exhaust plumbing of the TD1 is applied to the Ascot Scrambler; and with very good effect. It would be a mistake for the YDS2 owner to hang these tuned expansion chamber pipes on his stock bike, as they are matched to the port timing of the aluminum cylinders developed for the TD1 ; but, they do a lot to push the racing engine’s power up to the phenomenal 35 bhp that it is said to have. We are inclined to think that this power claim is very little, if any, exaggerated. The Ascot Scrambler feels like a good, strong 500 — and it goes like one.

It is worth mentioning that the racing cylinders must be fitted with great care. A Yamaha service bulletin informs us that the pistons must be lap-fit, and that the engine should then be run for 20-30 minutes at 40006000 rpm and then disassembled so that high spots can be polished away with #400 sandpaper. The bulletin also cautions that this process of running-disassembling-polishing may have to be repeated until all of the high spots are gone. Actually, this sort of hand fitting has long been an important part of 2-stroke race-tuning, but in all too many instances it is ignored. The problem is not peculiar to Yamaha; all motorcycle 2-strokes have trouble with cylinder distortion in the area of the ports, where there are uneven masses of metal that pull the cylinder out of round when heated by hard running.

Special pistons and rings are also used in the Ascot Scrambler (and TD1, of course). These pistons are made of a high-silicon aluminum alloy that has substantially less growth with increased temperatures than pure aluminum. And, the Lo-Ex alloy retains full strength even at high temperatures. The rings used in conjunction with this piston are 1.5 mm in thickness; thinner than the 2.0 mm rings of the YDS2. The rings for the current racing engine are Parkerized (an anti-scuff coating primarily intended to prevent damage during break-in); previously they were chromium plated.

The Ascot Scrambler has the YDS2’s 5-speed transmission, which is an asset in a scrambles, as well as roadracing, but doesn’t matter much in oval track racing because regulations forbid shifting gears once underway. In this transmission, where the drive passes across pairs of gears, there are slightly higher power losses, but in the Yamaha the losses are minimized by a very high primary reduction, which reduces the speed at which the transmission gears turn. Because the transmission is also of the cross-over type, with the drive coming in on the left (clutch) side and emerging on the right, the countershaft sprocket is unobstructed.

Changes in overall gearing are easily made, and there are many ratios available. The owner can select from no less than 16 rear wheel sprockets having from 45 to 60teeth, and can mix these with 13, 14 and 15-tooth countershaft sprockets, making 48 possible combinations in all. Somewhere in there, the owner is certain to find something to suit the conditions.

Lubrication for the racing engine is a bit different from that specified for the YDS2. The street machine runs on a 20:1 mixture of fuel and oil; the racer’s specifications call for a 12:1 mixture, using Shell 2-stroke oil.

The Ascot Scrambler’s frame is the same as that of the YDS2, of the two-loop type, made of round-section steel tubing: It is clean in layout, and strong, and offers good accessibility around the engine. For racing, the ultralight TD1 frame would be better, but it just might be a smidgin light for a really nasty, rough scrambles course. And, the AMA is occasionally a trifle sticky about outand-out racing equipment running in class-C events.

The suspension and brakes of the Ascot Scrambler are to all practical purposes identical to that of the YDS2. Most, if not all, of the Yamahas running on the dirt oval at Ascot have rigid struts or special frame members substituted for the standard spring/’damper units interposed between the frame and the rear suspension’s swing arms, but the front forks appear to be doing the job “as delivered.” There may be something lacking in the rear spring/damper units, as many people riding these bikes in scrambles substitute British made units. However, we found them to be perfectly satisfactory for the riding we did.

One thing that makes the Ascot Scrambler look very different from the YDS2 are the tires, fenders and wheels. The tires are great, large-section knobbies; there is no front fender at all and the rear fender is mighty sketchy; and the wheels are the same light-alloy lovelies that come with the TD1 road racer. And, of course, the saddle gives one a strong clue, as does the utter lack of any lighting equipment. The engine differences are there, but unless one looks closely the aluminum cylinders can go unnoticed and the carburetors, which are fitted with aircleaners, look identical to those on the YDS2.

An outstanding feature of the Ascot Scrambler is lightness and this affects the bike’s performance in more ways than one. It should be obvious that the combination of light-weight, high power-output and a 5-speed transmission coupled with a high (numerically) overall drive ratio would provide a lot of performance — and it does. The times and speeds obtained at the drag strip were absolutely staggering for a quarter-liter machine.

The light weight also makes itself felt in the handling department. Being light, body-english (even when the body involved is that of a smallish rider) can be applied with really impressive effect. The Ascot Scrambler can be “muscled” out of situations that would land most riders right on their ears if they were riding heavier machines.

With steering and suspension so much like that of a pavement machine, the Ascot Scrambler is not a universal off-the-road motorcycle. Its steering is quick, and it is not particularly stable in very rough going; partly because of the quick steering, and partly because the spring-rates and damping are not really right for that kind of work. On the other hand, it is just the thing for flat-tracking; or a west-coast style TT or scrambles, which are usually run over courses that have smooth, hard-packed surfaces. In this kind of an event, the handling and the whopping amounts of power on-tap make the Yamaha Ascot Scrambler a formidable competitor indeed. And, rather surprisingly, it is a relatively easy and comfortable machine to ride. The seating and handlebar — foot pegs — controls layout was very much to our liking. The seat itself is an especially good item: just firm enough, and long and flat so that the rider can shift his weight back for straightaway traction or forward to get a slide going in a tight corner.

The final attraction, for us, was the bike’s excellent finish — which is actually no more than we have come to expect from Yamaha. For a hare-and-hounds or motocross, a low-speed, high-torque single may be supreme; but, when it comes to high-speed action on fairly smooth clay, there is hardly any substitute for Yamaha’s highwinder. You just can’t beat all of that horsepower. A lot of people are trying, and very, hard, but most of the time they have to run the race in the Yamaha’s smokey wake just the same.

YAMAHA

ASCOT SCRAMBLER

SPECIFICATIONS

$745

POWER TRANSMISSION

DIMENSIONS, IN.

PERFORMANCE

SPEEDOMETER ERROR

ACCELERATION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

NOVEMBER 1963 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

The Service Department

NOVEMBER 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Around the Industry

NOVEMBER 1963 -

15th Annual Bonneville Speed Trials

NOVEMBER 1963 By Cycle World Staff -

The Worm-Wood Report

NOVEMBER 1963 By Clive Tweedley -

We Triumph At Bonneville

NOVEMBER 1963