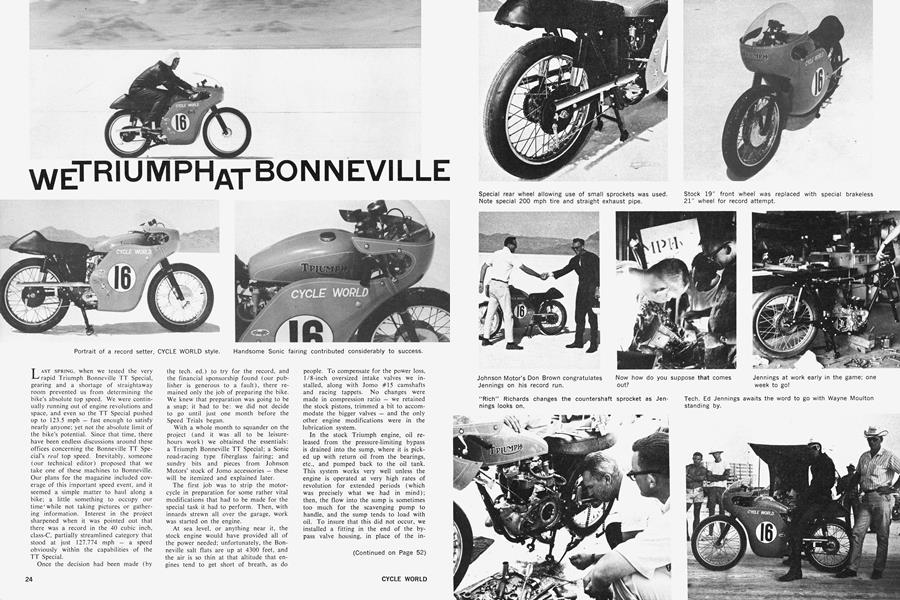

WE TRIUMPH AT BONNEVILLE

LAST SPRING, when we tested the very rapid Triumph Bonneville TT Special, gearing and a shortage of straightaway room prevented us from determining the bike's absolute top speed. We were continually running out of engine revolutions and space, and even so the TT Special pushed up to 123.5 mph — fast enough to satisfy nearly anyone; yet not the absolute limit of the bike’s potential. Since that time, there have been endless discussions around these offices concerning the Bonneville TT Special’s real top speed. Inevitably, someone (our technical editor) proposed that we take one of these machines to Bonneville. Our plans for the magazine included coverage of this important speed event, and it seemed a simple matter to haul along a bike; a little something to occupy our time'while not taking pictures or gathering information. Interest in the project sharpened when it was pointed out that there was a record in the 40 cubic inch, class-C, partially streamlined category that stood at just 127.774 mph — a speed obviously within the capabilities of the TT Special.

Once the decision had been made (by the tech, ed.) to try for the record, and the financial sponsorship found (our publisher is generous to a fault), there remained only the job of preparing the bike. We knew that preparation was going to be a snap; it had to be: we did not decide to go until just one month before the Speed Trials began.

With a whole month to squander on the project (and it was all to be leisurehours work) we obtained the essentials: a Triumph Bonneville TT Special; a Sonic road-racing type fiberglass fairing; and sundry bits and pieces from Johnson Motors’ stock of Jomo accessories — these will be itemized and explained later.

The first job was to strip the motorcycle in preparation for some rather vital modifications that had to be made for the special task it had to perform. Then, with innards strewn all over the garage, work was started on the engine.

At sea level, or anything near it, the stock engine would have provided all of the power needed; unfortunately, the Bonneville salt flats are up at 4300 feet, and the air is so thin at that altitude that engines tend to get short of breath, as do people. To compensate for the power loss, 1/8-inch oversized intake valves we installed, along with Jomo #15 camshafts and racing tappets. No changes were made in compression ratio — we retained the stock pistons, trimmed a bit to accommodate the bigger valves — and the only other engine modifications were in the lubrication system.

In the stock Triumph engine, oil released from the pressure-limiting bypass is drained into the sump, where it is picked up with return oil from the bearings, etc., and pumped back to the oil tank. This system works very well unless the engine is operated at very high rates of revolution for extended periods (which was precisely what we had in mind); then, the flow into the sump is sometimes too much for the scavenging pump to handle, and the sump tends to load with oil. To insure that this did not occur, we installed a fitting in the end of the bypass valve housing, in place of the indicator rod, and lead the bypassed oil directly back to the oil tank. This was the extent of engine modifications; we retained the standard 1 3/16-inch Amal Monobloc carburetors, and even used the exhaust pipes supplied with the a machine:

(Continued on Page 52)

1 3/8-inch upswept high-pipes of the type intended for scrambles and TT racing. No megaphones, no anything; we wanted to remain as near “stock” as is possible.

A lot of the “stock” approach went right out the window when we got to the matter of tires and gearing. It is required by regulation, at Bonneville, that high-speed machines use high-speed tires, and while such tires were available for the TT Special’s 19-inch front wheel, the 18-inch rear wheel was no-go. Moreover, it is not possible, within the dimensions of the Triumph’s cases, etc., to get the kind of gearing that would allow the kind of speeds we had in mind. Thus, it became necessary to fit a special rear wheel, which had the brake drum moved over opposite the sprocket. This permitted the use of substantially smaller than standard rear wheel sprockets. Luck was with us in this regard, for our good friend. Rich Richards (he of the potent drag-strip and Bonneville, 40-inch fuelers), had just such a special wheel — complete with a 20-inch rim and approved, high-speed tire. We were now all set in the wheels and tires department; or so we thought.

At this point we had the engine back in the frame, and the wheels mounted, and all that was required to make the motorcycle function was to rig a crossover linkage for the brake lever, which was on the left; the brake drum being now located on the right side of the wheel. The mounting plates on each side of the frame, which support the back of the transmission, were bored through, and a cross-shaft installed. A couple of levers and linking rods completed the connection to the brake and here again we fancied that we had the situation gripped tightly by the hindside. A hurried reassembly after a sprocket change was to produce errors that made this estimate of the situation appear, in retrospect, somewhat optimistic.

The fairing was fitted — a less difficult task than one might imagine — and sent out to be painted and we then faced the problem of a seat and fuel tank. The stock components would not do: the tank was wide enough so that the low, “clipon” handlebars we had installed made contact even at small steering angles, and the seat’s deep padding, while superbly comfortable, raised the rider’s rump upward in a most unaerodynamic fashion. Again, it was Jomo to the rescue, with a racing seat and fuel tank much better suited to the job. Both were of molded fiberglass, and the seat entirely covered with leatherette. These are new items in the Jomo line, made to their specifications by Custom Plastics — who do some of the best work in fiberglass we have ever seen.

All of this takes a trifle longer than the telling, and by the time the bike was ready, we had to work right down to the last moment and went flying off to the salt flats without ever having even started the TT Special’s engine. Our naturally high hopes were leavened by the nagging knowledge that everything was not as it should have been: there was a suspicious tightness in the engine when the pistons were eased past top-center. However, time had run out and it was time to leave. Part of the crew had a job of reporting to do and there was no time to dawdle.

That suspicious tightness was corrected after our arrival at Bonneville. Rich Richards, who is more than a little familiar with Triumph engines, offered the opinion that the pistons were contacting the intake valves. So sure of his diagnosis was he, that he pitched right in and helped us pull down the upper end of the engine for a look. He was disgustingly correct: in the great rush to do it all in one month, the necessary check of clearances had not been made and the intake valve heads were just pipping the pistons.

To correct this, the valves were pocketed into the head a bit deeper, the engine reassembled, and a (by this time) weary CYCLE WORLD crew wheeled their entry out to the salt. We were greeted with polite but unimpressed interest by the Bonneville regulars, who eyed our straight pipes and “showroom” carburetors dubiously, and whose faces clearly showed that they considered us mere babes in the woods. To tell the truth, after looking around at the exotic and highly modified machinery there (you have never seen so many GP carburetors in one place), we were beginning to feel a bit the same way ourselves.

The fretting and doubt was for nothing. In what remained of the day, we tuned up to within 1 mph of the record, and went back out early the next day with fire in our eyes (and stomachs, too: we

had celebrated that night). The first order of business was a change of gearing, promptly done, and then we made a run at just over the existing record, which qualified us to make an official attempt the following morning, and then capped it all with another run (after a change of jetting) at 135.74 mph. Ah the joy! To sit in the shade and watch the scoffers edge up to take another look and walk away muttering to themselves.

To those readers who don’t think 135 mph is fast, we would like to say that under ideal conditions it might not be; but the salt was very rough and slippery this year, and the barometeric pressure was going up and down like a yo-yo, upsetting everyone’s carburetion, and at that point in the speed trials, we were going faster than almost everyone. Faster, in fact, than anything else in the 40-inch class, and that included some fast nitroburners. Also, we were faster than all but a couple of the big V-twins. •

In any case, our technical editor, who made the decisions, did much of the preparation work and handled thé riding chores, was vastly impressed with Bonneville. The tuning difficulties are enormous up there, and he remarked that it takes a lot more effort on the part of the rider than anyone who hasn’t been there would expect. We had all assumed that the rider would not he required to do anything beyond turning up the wick and pointing the hike down the course — and as far as it goes that proved to be correct. However, running flat out for long distances is very hard on engines, and the rider must judge speed and distance so that he arrives at the timing lights at the moment the hike reaches its top speed. It is necessary to build up speed smoothly; both to avoid unnecessary strain on the machine and to prevent wheelspin. The salt is rough, and extremely slippery at times, and a rough, slam-bang shift with a lot of throttle can put the rider on his ear quick as a wink. And, even when ridden smoothly, there is a fair amount of rear wheel slippage and the bike tends to snake back and forth slightly all the way. The whole thing is much like riding fast over packed, powdered snow and until the rider becomes accustomed to the slithering about, he will be thinking that perhaps this is not such a good idea after all.

On the morning of the record runs, everything went so smoothly that it was almost anticlimatic. The hike fired instantly, as it did invariably, and Our Hero was off down the strip, leaving a fine rooster tail of salt hanging behind the rear tire. Two miles to build up speed, then a timed mile, and two more miles to coast to a halt. Luck was with us and we had cool air and no breeze; the speed was an even 140.025 mph. Unhappily, a light breeze came up while we were waiting for our turn to take a run in the opposite direction, and this breeze dropped our return speed enough to pull our two-way average down to 137.075 mph. Not as high as we would have liked, and not as fast as the hike was capable of running, but there is a time when one must stop fooling around with the chalk and either shoot pool or put down the cue.

After pushing up the class record almost 10 mph, we decided to have a try at 150 mph. More fiddling and a set of megaphones, and then back to try again. Here, our esteemed publisher, who has about as much sporting blood as is even close to being healthy, wanted to have a whack at it, and we sent him off down the salt with promises of high excitement. The promises were fulfilled beyond our wildest dreams. During his run, a float needle stuck open, and when he shut down at the far end gasoline poured up and out of the float chamber and drenched the left side of the motorcycle. Then, to complicate things, an improperlycrimped cotter pin came out, a brake rod dropped free and the brake pedal lever dropped down and dug into the salt. This drove the lever back, shearing away the pivot pin and bolt, and carried away the left megaphone. In accordance with Murphy’s Law, the engine at that moment decided to backfire and in a flash the motorcycle was in flames — and no brakes. The front wheel brake had gone when we changed to a special 20-inch racing wheel and tire (to avoid a steepening of the steering head angle which occurred when we had installed the big back wheel). Fortunately, the air blast kept the flames down until the bike had slowed considerably and then His Nibs simply bailed out. The bike crashed, more fuel spilled, and the resulting blaze destroyed the motorcycle’s chances of running again at that meet. A great column of smoke went up, of course, and in a twinkling there were men 'on the scene with fire extinguishers, and this prevented more extensive damage, but the CYCLE WORLD Triumph was out of it.

In a sense, we were lucky. Good leathers kept the publisher from even getting singed in what could have been a very nasty accident, and we had our record. Ironically, we didn’t know it at the time, but the bike had also won for us a “best-looking” trophy — the judging obviously being done before the fire.

That ends the story for 1963; but there will be more to report. The bike had the potential to go much faster, and we mean to have another go at it next year. We will continue to use a fairing; it is a very great aid in reducing drag. One scoffer rashly offered to bet $25 that the fairings wouldn’t make 5 mph difference in the bike’s top speed, and the man from Sonic, who supplied the fairings, took the bet. Immediately after the record runs, and before making any other changes, we pulled the fairing and ran through “bare.” The speed? Only 124 mph. Fiddling the gearing would have reduced the margin, but the difference is clearly there.

Streamlining is always a help, obviously, but this is the kind that can be applied to a touring bike, and it is a kind used extensively in road racing, and that is why we elected to run in the partially streamlined class. Any results we obtain have a direct relationship with what can he done with an ordinary, touring motorcycle. We intend to limit engine modifications in the same interest. Certainly, we could run faster on nitro and alcohol, but we want to stay with fuel that comes out of the neighborhood gasoline pump. And, too, there is certain satisfaction to be had in getting the power without going to exotic nitrates of alcohol.

We have a full year to spend in a more serious Bonneville attempt; this year we simply tried to get what the manufacturers had built into the engine. Our present record represents only what can be done with a properly tuned, nearly stock machine put together with pieces available “off the shelf,” and not even everything available there. The speed says a lot more for the Triumph than for our abilities as tuners; next year we will extend both the machine and ourselves a bit further and see what happens. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

NOVEMBER 1963 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

The Service Department

NOVEMBER 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Around the Industry

NOVEMBER 1963 -

15th Annual Bonneville Speed Trials

NOVEMBER 1963 By Cycle World Staff -

The Worm-Wood Report

NOVEMBER 1963 By Clive Tweedley -

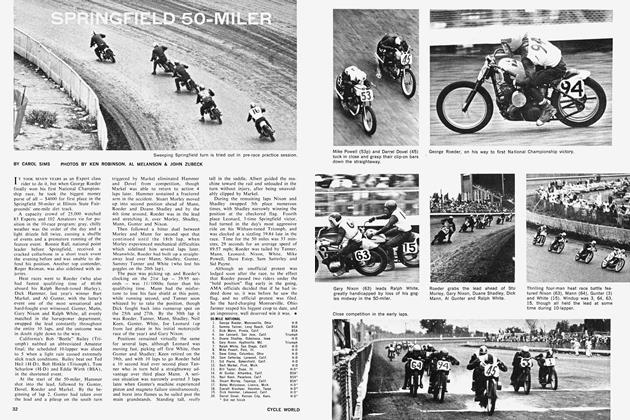

Springfield 50-Miler

NOVEMBER 1963 By Carol Sims