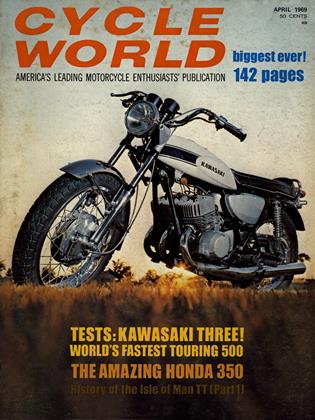

KAWASAKI 500 MACH III

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Amend The Old Proverb To Read: There’s No Substitute For Cubic Inches, Except More . . . Efficiency.

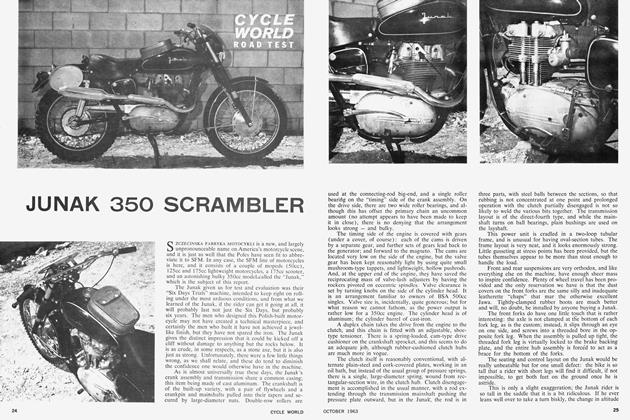

KAWASAKI’S NEW 500 has got to be the kinkiest street bike ever! It’ll raise the hairs on the back of a rider’s neck, or turn them grey in 13 seconds flat. At top speed, it will run faster than the Osaka Express. It will trounce any mass production motorcycle that comes in full street trim, regardless of displacement. The stench of rubber smoke and a 100-foot-long black strip give ample evidence that it has departed, yet it is as docile as a kitten. Its p.o.e. price of $999 is incredibly low, but it puts out more honest-to-goodness horsepower than a Manx Norton.

CW Editor Ivan Wagar rushed to Japan when he heard the tales about Kawasaki’s modern new way to commit harakiri. After a preview demonstration and technical conference with the Mach III development engineers, he returned home—somewhat wide-eyed—and the staff was forewarned. On the day the beautifully designed three-cylinder was delivered to the CYCLE WORLD offices, one wag suggested a lottery to determine who wouldn’t have to ride it through the quartermile. Another went out and bought a new face plate, figuring that he would otherwise get his helmet sucked off the top of his head. But the trepidation was not that necessary. The Mach III, in spite of its racer-like tendencies, is far from being a beast. It starts easily, has terrific brakes, is extremely manageable in traffic, and forgives the rider if he lets the engine speed drop too low. One would never know that the 500 is a racer in disguise, were it not for the fact that the front wheel readily lifts into the air if the throttle is jerked on in the first three gears.

It is not at all invidious to compare its output favorably to the Manx, for its performance is everything Kawasaki claimed it was. Even the average rider may rack up a 100-mph standing start quarter, and, with some practice, get his e.t. into the 12s. Drag racer Tony Nicosia already has managed to push his own fully-equipped Mach III through the LADS timers at more than 109 mph. A 60-bhp 500-cc production motorcycle would have seemed impossible just a few years ago. But it had to happen. The performance market is “where it’s at” in America, and the giants of the Japanese motorcycle industry have the technical resources to exploit it.

Kawasaki began development of the Mach III in early 1967.

While 500 cc is certainly not too large for a Twin, the factory engineers opted instead to build a Three. Although there is a certain mystique that goes with any motorcycle having more than two cylinders, Kawasaki’s choice of three has solid reasoning behind it. Not the least of the advantages is the fact that individual cylinder power impulses are less for a Three than for a Twin of the same displacement. The smaller torque peaks mean that a lighter clutch and transmission may be used to carry the same, or even more, power. Therefore, if it is properly designed, a Three can be within the same weight category as a Twin, even though there will be more individual components in the Three. Putting theory into practice, the Mach III wet clutch—consisting of seven metal and seven friction plates controlled by five springs—holds up extremely well. There was no indication of slippage, even after more than 25 scorching dragstrip runs.

Quarter-mile acceleration tests, incidentally, are accomplished in most graphic fashion. The technique is roughly the same as would be used to get a thundering, one-gear fuel bike off the line. No prissy clutch-slipping start on this baby. No sirree. For the best e.t. and the magic “ton,” you wind the R’s up to eight grand or more When the Chrondek turns green, you let it all hang out, and God help you if the bike is not absolutely straight up and down. Head and body must be as far forward as possible, for the weight distribution—57 percent rearward-is absolutely no help in keeping the front end down.

Where does all that brute horsepower come from? After all, the 500-cc Mach III, compared to other superbikes, is a relatively small displacement machine. In a two-stroke, power comes from port area, and in this respect a Three has a great advantage over its rivals with fewer cylinders. A cylinder has a maximum port area potential, the limit of which is defined by the cylinder wall area. It may be exploited fully by efficient engineering, but it may not be surpassed. Simple mathematics will show that a Three has more cylinder wall area than a Twin or Single of like displacement, and therefore more port area potential. It is not at all unreasonable to expect a port area increase of about 25 percent. As the power to be extracted from an engine is dependent on how much fuel charge can be packed into the combustion chamber, that 25 percent increase in port area will yield a power increase of about 22 percent—assuming, of course, that the design is properly executed. There is an additional power advantage to be gained from a three-cylinder engine in that the bores are smaller, so the flame travel is shorter. Fuel vapor swirling around in a larger cylinder requires more time for complete combustion. While combustion in a large bore may be satisfactory at relatively slow rpm, efficiency drops at higher engine speeds, because the entire fuel charge may not have burned before it is spit out the exhaust.

Proper design execution takes into account many things. The paramount problem with a three-cylinder layout is the need for sufficient cooling to the critical middle cylinder. Not only is there a certain amount of heat transfer from the outside cylinders, but the middle pot receives fouled, less effective airstream from the front wheel and fork legs. The outside cylinders are far enough from the center line to pick up a clean air flow, and do not present as great a cooling problem. First rumors had it that the new machine would have a horizontal middle cylinder, permitting larger fins without increasing the overall width of the engine. But, Kawasaki, an aircraft firm of world renown, began a wind tunnel program early in the development stages of the Three and concluded that it wasn’t necessary to extend the middle cylinder fin width to a greater amount than the space dictated by the crankshaft assembly. In fact, the engineers spent more time finding ways to shorten the crankshaft than on cooling the cylinders. They were obviously successful, for the total engine width of the Three is less than an inch greater than that of the A7 350-cc Twin.

While still in the initial drawing board stages, the engineers realized that conventional breaker point ignition systems would not cope with the requirements of a three-cylinder two-stroke. At 10,000 rpm the engine requires 500 critically timed sparks per second. Profiting from the experience of other manufacturers with different GP four-cylinder racers having electronic ignition, Kawasaki developed a capacitive discharge system delivering 25,000 volts to the plug. At this point, it was apparent that conventional spark plugs would have a very short life, due to the high secondary voltage. So the design department borrowed a page from American outboard technology—the surface gap spark plug.

Unlike the spark plugs to which we have been accustomed in the past, the surface gap plug does not have an earth electrode. It is, for all intents and purposes, a spark plug without the side electrode protruding under the center conductor. The voltage required to fire such a spark plug is much greater, but the spark is not concentrated at one small spot. The spark will find its path to ground at any point around the circle of the plug body. Thus the problem of erosion of the earth electrode has been overcome; plug gap cannot change during use. The surface gap plug has a much greater life span than the conventional earth electrode variety and, because of higher spark efficiency, gas mileage is increased.

Another first for Kawasaki is the elimination of rotary disc valve induction. Kawasaki has, since development of its first two-stroke design, relied on rotary valves. On the Three, however, the width of the engine would have been prohibitive, and a rotary valved center cylinder is almost an impossibility. From the very first idea stages, the Three was conceived as a piston port engine, which is not all bad. Besides decreasing the overall size, a piston port two-stroke is quieter in operation than a disc valved design. Even a fiber disc creates noise as it flutters during the sharp induction cycles. On a three-cylinder engine, with its inherent higher intake pulses, the noise level of the discs would have been considerable. Also, piston port engines require less attention to lubrication because whether the engine is gasoline-oil mix or positive oil fed, a piston port design permits more complete swirl through the crankcase and lower end components.

A logical conclusion when considering a 500-cc threecylinder would be that the engineers had adopted that size to take advantage of existing parts from the extremely successful 175-cc Bushwacker. That is not the case. The Three is a wholly new design, and none of the parts are interchangeable with an existing Kawasaki model. The brilliant young Otsuki and his design team started with what they considered the ideal bore/stroke dimensions for a piston port engine. Then, to keep the crankcase chamber dimensions to a minimum, the shortest possible connecting rod length was used. The connecting rods, on centers, measure a mere 4.33 in. Sealing between the crank chambers has been accomplished by using labyrinth seals, which permit excellent sealing qualities with very low drag on the shafts. Kawasaki’s “Injectolube” positive feed system supplies oil to the left-hand main bearings only. A steel plate with bonded neoprene collector rings picks up the oil supply to the crankpins and big end bearing assemblies. Normal crankcase swirl then mixes the oil from the big end with the incoming gas-air charge, and drain holes from the transfer ports allow lubrication of the right-hand main bearings.

The two main crankcase components are split horizontally through the center line of the shafts. To facilitate machining operations, the main bearing outside diameters are greater on the left side of the engine.

Kawasaki is to be commended for its ability to perform a very intricate machining operation with perfect results: horizontally-split crankcases on a three-cylinder two-stroke. Some European counterparts suffer the antiquated arrangement of several vertical joints, even on four-stroke designs where sealing is not nearly as critical as it is on a two-stroke. Because the crankcase actually is in the induction system, the crankcase sealing of a two-stroke becomes extremely important; the smallest pin hole will upset carburetion to the point of piston seizure. To facilitate machining operations, Otsuki made the three left-hand main bearings larger, by 10 mm, than the three main bearings on the right side of the engine. The 52-mm bearings on the right side of the engine allow a sufficiently low peripheral velocity to keep heat generating capabilities to a minimum, while the larger left-hand bearings actually are oversized for machining purposes only.

Both shafts in the five-speed transmission have ball bearings at the live ends, and needle roller bearings at the dead ends. A pair of square-cut primary gears feeds crankshaft power to the clutch, which features an aluminum center hub. The alloy clutch hub and square-cut primary gears are just two of the many items in this engine which make it look far more like a racing unit than the powerhouse foj; a mass-produced street motorcycle.

The aluminum cylinders have cast-in iron liners. The ports and liner windows are well matched in the “as cast” form. Two-ring pistons feature expanders inside the lower rings to reduce noise. Also, cylinder head fins are bridged, in the interest of quietness. Fortunately, these steps have been taken, and tend to keep the somewhat noisy primary drive train sounds to a reasonable level.

The three 28-mm carburetors are mounted directly on the back of the cylinders, and are operated by a single twistgrip cable through a three-branch junction box under the gasoline tank. A second twistgrip cable, operating in conjunction with the throttle, governs the Injectolube oil pump output. A large, one-piece, three-branch moulded neoprene housing feeds clean air from the filter to the individual carburetor intakes. The filter is extremely large to handle the very high volume of air consumed by the engine, and features a washable paper filter element. Although the filter and intake housing are very large in size, intake noise is almost undetectable, due to the sound damping effect of the mass.

Overall, the engine/transmission unit is a very tidy package, and smaller in size and weight than many of its counterparts. Normal sitting position on the machine does not require the feet to be farther apart than on any modern two-stroke with more than one cylinder. The riding position, in fact, is comfortable and relaxed. The gear shift lever has such a gradual angle from the pivot that the ball of the foot actually contacts the arm before the toe operates the shifter pedal. Several suggestions were put forth to correct this minor problem and production versions do not suffer this trouble.

The seat is very comfortable, whether riding solo or double. The turned-up portion at the rear presents a welcome rest for the long-distance traveling companion. The chrome-plated loop behind the seat meets all of the legal requirements and makes solo riding a great deal more comfortable without the ridiculous strap, which usually crosses the seat just where you want to sit when going fast. It would be difficult to select a more comfortable set of handlebars for long-distance touring. The width, height and angle are ideal for the average sized rider, and bars to seat, seat to footpeg relationship is beyond criticism.

Riding the Mach III is an exhilarating experience. The lack of an electric starter is no handicap whatever; with individual cylinder displacement at something like 165 cc, the kick start pedal spins the engine over at a high rate of revs, and effortlessly. At least one pot fires before the kick pedal reaches one-third stroke and the engine is running. There is no vibration. The engine runs like a turbine throughout the rpm range. The first prototype machine had rubber engine mounts, but strange harmonics at various points in the rev range caused the engineers to try mounting the engine solid in the chassis. The results were surprising; flexible mounts were not necessary.

With no load on the engine the throttle is extremely responsive. The slightest movement of the twistgrip causes the engine to speed up or slow down and, with the absence of vibration, it is difficult to know exactly how much throttle is required to get the job done. But, this is one machine where too much throttle is possible, and very quickly. Once underway it is best to change to second gear as soon as the machine is moving. The engine is slightly peaky. It shows a definite desire to produce strongly around 6000 rpm. And, although peak horsepower is listed at 8000 rpm, the engine is quite willing to go to 9000 before falling off.

The tires fitted as standard are special Japanese Dunlops. The tread pattern is exclusive to this machine, at least for the present time. The road holding qualities of the tires were quite good and, in most respects, fairly close to road racing standards. The tires, plus a general feeling of lightness, conveyed confidence at speeds below 100 mph. There is, however, a slight waggle above 110 mph when the machine is banked over near the limit. This condition was quite apparent at Yatabe test track in Japan, a high speed oval with 35-degree banking, where the machine could be ridden at 125 mph without shutting off. On the banking the Mach III was as stable as a thoroughbred road racer. On the flat, lowest lane, however, slight irregularities caused a slow, predictable yawing. Fortunately, and probably due to the hydraulic steering damper, the yawing effect did not become worse when throttle opening was increased or decreased. It is a pretty good bet that the sensation was caused by the tires, rather than by the machine itself.

At no time during the test was there any indication that exhaust pipe or muffler grounding would be a problem. However, while “getting down to it” on a tight, windy stretch of California road, it became increasingly easy to graunch the center stand while turning to the left. The front fork is a new design for the Three and strongly resembles a Ceriani in appearance. It has a super-slim configuration for two reasons: American buyer appeal, and to present as little restriction or disturbance of air flow to the cylinders as possible. Fork travel is long for a street machine, but damping throughout full

travel is excellent. The rear legs, also, are long travel, and well dampened. The external springs have the now familiar inside sleeve to maintain coil alignment during operation.

The chassis features a very wide double-loop lower section, which extends under the engine and arcs upward to join the top frame members at the upper mount for the rear suspension units. Two smaller diameter reinforcing struts join the swinging arm pivot area to the upper frame just ahead of the seat. The well gusseted, bushed swinging arm pivots inside the main cradle, on a welded-up box section. Two loop sections, to carry mufflers and passenger footpegs, extend rearward from the main cradle. The frame is unusually strong. Frame flex, if it did exist, was not apparent during the test.

Repeated high speed stops did not disclose any braking deficiencies. The two-leading-shoe front stopper performed the task of slowing this Walter Mitty Isle of Man winner very admirably, but without locking the wheel. The rear brake, of course, would lock up the back end any time, even after several high speed stops.

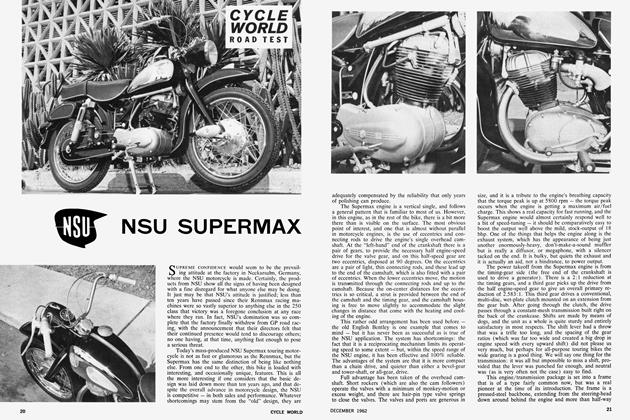

The Mach Ill’s styling is so tasteful that it demands comment. Long tank in white. Broad blue, outlined racing stripe. Slim front end. Racer-like (but legal 85 db maximum) silencers, one on the left, two on the right a la MV-3. Chromed steel fenders. “Mach III 500” in raised metal letters on the side covers. All these elements produce a sleek, restrained look that one associates with a $14,000 sports car. The Mach III looks fast, but in a subtle way. Like Ferrari, or Porsche, it doesn’t have to pound you over the head with garish, nouveau trappings of speed. It exudes, because it is.

The Kawasaki Three is a masterpiece, from any point of view. Calling it fast isn’t enough. Rather, it is the fastest production touring machine available to the general public. Unrestrained, boiling id lies waiting for the turn of the throttle. Many will have the cash to buy it, but fewer will have the “hair” to ride it to its limit. It requires a strong mind, great judgment and enormous self-discipline.

So superb a machine will be the subject of controversy for a long time to come. Some will deny that the Mach III even exists or can do what is claimed for it. And bench racers everywhere will argue themselves into fits of furor. [Ö]

KAWASAKI

500 MACH III

$999