[TECHNICALITIES]

GORDON H. JENNINGS

A FUNNY THING happened as we were preparing to go to Daytona this year. The editor had decided that the race track itself would be a perfect observation post for your roving reporter, and in due course we sent in an entry for the Expert/ Amateur 100-mile event for 250cc-class motorcycles. On the basis of my experience with the AFM road racing club, the AMA had given me an "Amateur" competition license; and we had a Ducati Diana 5-speed to convert into a proper racing machine.

Unfortunately, matters complicated themselves considerably when the Yamaha TD-IB came our way. Very little experience on the Yamaha was needed to convince us that some elaborate fiddling would be required to make the Ducati competitive, and there was really not time to do the job right. And then there were delays on the part of suppliers, and a lack of time imposed by the necessity for producing a magazine (it is a terrible thing when one must allow business to absorb hours that could be spent on racing). In the end, time simply ran oüt, and we were forced to do something drastic.

One fine Friday, with slightly more than a single week remaining before the start of practice at Daytona, I grew very weary of trying to put together a Ducati that would match the speed of Yamaha's TD1B, and decided to shelve the project until it could be done right. We then came to the conclusion that the most sensible means of matching the Yamaha's speed was to simply get a Yamaha.

A single phone call to Yamaha International produced a new, fresh-from-thebox TD-IB (we mention this just in case you were wondering if the TD-IB is, in fact, available), and I carted this home Friday night. Saturday and Sunday were spent preparing the bike, which included mounting a fairing; on Monday it went to the paint shop, and on Wednesday it was loaded into a Daytona-bound Dodge panel truck (courtesy of the Edwards Wirth, father and son).

As you will appreciate, in the time available there was no chance of doing anything fancy. The brake drums were wiped clean and surplus grease removed from the cams and shoe pivots, and a set of Dunlop road racing tires mounted (the bike is delivered with Yokahama racing tires). Virtually all of the nuts and bolts are pre-drilled for safety wire, so I went over the bike tightening and wiring everything. The cylinders were removed, more for precautionary inspection than anything else, and a bit of filing matched the carburetor flange to the intake port; the transfer ports and the exhaust port were not touched. I did discover that the expansion chambers were binding against the frame, and this was corrected by elongating the mounting holes to lower the chambers slightly. Finally, the ignition system was inspected, and timed, and the float-level checked. One way or the other, we were ready to find out what it is like to go racing with a motorcycle virtually stock out of the box.

You may have noticed that I have not made any mention of either a break-in, or shakedown run - and for a very good reason: the engine was not even started until my arrival at Daytona. The people at Yamaha said the machine needed only 15-20 miles for break-in, and there was no chance to do this until practice started. So, I simply used the first four laps of practice for break-in, and then started flat-out.

Actually, the initial period of flat-out running lasted only two laps. Just as I was completing the second lap, the engine coughed noisily and the left cylinder blew a sizeable portion of its piston crown right down into the crankcase. A fine way to start a week of practice and racing.

(Continued on page 18)

TECH.

With the cylinders removed and the pistons exposed (a process that takes only a few minutes) something of a mystery was revealed. Spark plug and piston crown color on the right cylinder showed a nearperfect mixture, while the left cylinder, which was being fed through an identical 190 main-jet, looked horribly lean, and that was obviously the source of the holed piston. And why was the left cylinder running lean? I am still not absolutely sure. A check of the ignition timing eliminated that as the cause, and stripping the carburetors revealed nothing that might account for the trouble. The only thing I could think of then, or now, is that a stiff fuel line was transmitting vibration to the left float chamber (these chambers are mounted in soft rubber) and making the fuel froth. The TD-IB is fitted with very soft fuel lines, but one was missing on my bike and I was silly enough to make-do with a replacement, hard-rubber line that would transmit more vibration than the original.

In any case, I replaced the stiff fuel line, and had no more difficulty. I started with the same gearing as that used on the Yamaha Team machines (these were entered by Yamaha International) and ultimately went to the 210 main jets they were using. Unfortunately, my bulk and weight did not mix well with 18-tooth transmission and 34-tooth rear wheel sprockets, and I eventually had to hang on a 36-tooth rear sprocket. With this gearing, my bike would pull the full 10,500 rpm (where the red line starts) in 5th gear, and that gave me about 126128 mph around the oval. The Team bikes (which, incidentally, had very little more done to them than I had done to mine) would top 130 mph. When my bike was carrying the 18/34 gearing, I actually saw 10,300 rpm, or 131 mph, but the buildup to that speed was rather slow, and any wind made it impossible to get the revs, so I considered that the 18/36 gearing was a good compromise.

Incidentally, while the TD-lB's instruction manual asks for a fuel/oil mix of 16:1, I used that only for the first 30 miles. For most of practice, and the race itself, the engine was lubricated by a 24:1 mixture of Pure premium-grade gasoline (supplied at the track) and Blendzall racing castor oil. Some of the Team bikes were running Blendzall at 26:1, and I was assured that mine would get along very nicely on the same, but I was chicken. Anyway, I did use the 24:1 mix, and got a 600 rpm boost in 5th gear over the 16:1 mix with no other changes. It is worth mentioning that none of the Yamahas running that 26:1 mixture had the slightest bit of bearing trouble.

Apart from the holed piston, the only mechanical problem encountered in practice was occasioned (I think) by the spark plugs I was using. The Team Yamahas were sparked by NGK, but I used Autolite AG403 plugs; preferring the Autolites because they are good plugs, and because the NGK plugs (which are also good) are not as familiar to me. Having used the Autolites for some time, I can "read" them easily and that was the reason for my preference. However, I had some trouble in that the sharp edge at the hole where the ground wire is pressed in (these are racing plugs) caused galling of the threads in the head - which is cast from a very soft aluminum. This bit of business eventually stripped some of the threads from one plug hole, and I had to replace the head. But, I overcame this difficulty by filing away the sharp edges in the plug threads where the ground wire hole comes through. Live and learn. Aside from this, I was very pleased with the Autolite plugs. I used the same plugs for starting, warm-up, practice and racing, and the engine never missed a beat. It would even idle fairly well.

One small (I thought) difficulty encountered in practice was that the fairing, which was not made for the Yamaha, would "ground" when cornering hard. Not wishing to do a lot of on-the-spot modifying, I left matters as they were, and it was a bad choice; more of this later.

Whatever difficulties I had back in the garage area, it was all made worthwhile once I had the Yamaha out on the track. Good handling and good brakes I had expected, but I was pleasantly shocked to find that this little 250 would run down the straights with many of the big bikes. At Daytona, all Amateurs practice together (as do Exoerts and Novices) regardless of the displacement of the motorcycles they are riding, so I had this rare opportunity for comparing performance. I recall (with a glee that is really not worthy of me) several instances when the Yamaha would pull right past moderately good-running Triumphs, and even one 45-cubic-inch KR Harley-Davidson. Of course, these were not the fastest examples of the make they represented -but then, neither was my Yamaha. What the really fast TD-IBs must have been doing to big-bike morale is terrible to contemplate.

In this connection, it is interesting that, unlike last year, the 250-class motorcycles did not "qualify" around the oval. Instead, we qualified for the 100-miler in heat races, and perhaps that is a good thing. Fast qualifier among the big stuff was a Harley-Davidson, at 133 mph, but down in the middle of the field the speed was not much over 120, and it seems overwhelmingly likely that all of the Yamaha TD-IBs would have qualified into the first third. I think mine would have done a flying lap at about 125 mph, and that would have given me a spot in the early-twenties among the big-bike qualifiers. The Yamaha International-entered TD-IBs would have done even better, obviously, and I cannot help but think how much fun it would have been to have one or two 250cc Yamahas in the front row for the start of the 200-mile race for 500cc ohv and 750cc side-valve motorcycles.

(Continued on page 20)

TECH.

Insofar as other 250cc bikes were concerned, it was obvious almost immediately that the Yamahas were going to win everything but the starter's undershorts — if they ran the distance. A good measure of their speed was provided by the amount of time others devoted to discussions of Yamaha reliability. The HarleyDavidson factory-entered Sprints were very fast, as always, but not quite fast enough. The Ducatis, which were very special machines with new frames, engine cases, and a super-big 4-shoe front brake, did not begin to be quick enough — even though the Chief Engineer and sundry mechanics from the Ducati factory were on hand to see to their health. I was very sorry to see the Ducatis being ground under, for it is a good motorcycle, and has a considerable potential for road racing — which remained potential alone at Daytona.

With my usual good fortune, I drew a last row starting spot in my heat race, and then compounded the problem by almost stalling the engine when the flag dropped. Even so, within the allotted 4 laps, I managed to claw my way up through the pack from about 40th into 17th place at the finish, and that gave me a better (I suppose) spot for the 100-miler: 8th row, center, in a starting field of 106 bikes.

Within moments after the start of the 100-mile 250cc race, I discovered a flaw in the great scheme of things. The winners of the heat races, who were on very fast motorcycles, occupied places right up in the front row; but there was also a lot of fast equipment in the pack. Consequently, on the first lap (which is made around the oval; you turn into the infield on the second lap) most of the field stayed packed together, as the dense traffic made it most difficult for the faster bikes to thread through. Had we qualified for position on the basis of flat-out speed around the oval there would have been much more of a tendency for the field to string out, and that would have given everyone more room. In short, when the first lap is made around the oval, then grid position should be assigned according to speed around the oval, for that is the only thing that will open up the field enough for reasonable safety. I suppose it is exciting to have most of the bikes come around in one big, howling clump, but it is a trifle unsettling if you happen to be stuck in the middle of that clump.

As a matter of fact, on the first lap I was trapped in the middle of the pack and grinding down the back straight at about 120 mph (with the throttle partially rolled back and looking for openings) when what to my wondering eyes should appear but a motorcycle, slithering along sideways with smoke pouring from the tires. Somehow, Î nipped past but apparently everything went wrong shortly thereafter. Emerging on the back straight on the following lap, I saw that the flashing caution lights were on, and officials were making a lot of gently-gently motions while others cleared away an amazing amount of debris. I understand that a blown engine precipitated all of this action, and that at least one of the lads was rather badly injured. In any case, I "do hope that something is done to open uo the field next year. Or, better, that the starting field be limited to perhaps 60 motorcycles; instead of 106.

(Continued on page 22)

TECHNICALITIES

Meanwhile, back in the race, I was working up through the field (and, honesty compels me to admit, getting worked by a couple of the faster fellows who had been trapped in traffic at the start). At this point in the game, I gave myself a large-size thrill when trying to nip past a group of riders down in the infield. They were all lined up on the left, ready to take a 180-degree righthander, so I came zipping down on the inside, braked hard, and flung the machine into the turn. It was here I discovered that the fairing grounded badly when the bike was being cornered at the maximum, and when the side of the fairing hit the road surface, the rear wheel lifted and a mad slide ensued. For one brief, awful moment, it appeared that I might go down and take about a halfdozen others with me, but the Yamaha crawled back up on its tires and continued on around. It was a near thing, and rather a strong indication that I would have to ride more conservatively for the rest of the race.

From this moment, I knew I was in trouble, for the quality of the competition at Daytona does not allow one any handicaps. Then, right at the end of the third lap, a real disaster struck. lust as I was peeling off to turn into the infield section, and shifted down from 5th to 4th gear, there was a loud bang and this time my heart really sank. From the bang, and the steady roar that followed, I knew that an expansion chamber had split wide open, and I also knew what the result would be: an almost complete loss of power on the affected cylinder.

There was a marked drop in power when accelerating away from turns down in the infield, but I was to discover the true enormity of the ill-fortune that had overtaken me when I swung back out on the oval. Acceleration up to speed was sluggish, and I could not use 5th gear at all. The engine would pull only 9800 rpm in 4th, and the lap before it had given me 10,500 in 5th.

A problem concurrent with the big drop in power was a big increase in noise. I had, in effect, a long, large megaphone with its end just ahead of my right foot, and the fairing carried the sound right up to my head. For a couple of laps the noise was almost intolerable and but for a determination to at least finish, I would have pulled in. Then, the noise seemed to abate somewhat, and at half-distance it was no louder than before the chamber broke; although there was no recovery of power. What I did not realize, was that I was going deaf. At the end of the race, after shutting down the engine, I found that I could hear nothing but a non-existent surf, booming in my ears. Fortunately, there was a noticeable improvement within a few hours and full recovery after a couple of days. The only thing from which I did not recover was a feeling of frustration over finishing 34th with a motorcycle that was entirely capable (even under my not entirely expert piloting) of placing me up among the first ten. Breaks of the game, and all that.

Bad luck or not, I did learn a few things from this experience. The most obvious thing was, of course, that Yamaha's TD-IB is the fastest 250cc production racing bike available in this country today. Supertuners can get a lot of bikes to go along smartly with enough fiddling; but on a box-stock basis, nothing will touch the TD-IB (this will get me a lot of nasty letters, but it is true nevertheless — as anyone who was at Daytona will confirm). Second, I learned that while Daytona is something less than the ultimate in a riderchallenge, it does give the motorcycles an incredible workout. A fast 250cc bike, for example, is on the oval, running at full throttle, for over a minute, and I would estimate that there is a period of at least 50 seconds at full throttle and maximum revs. Holding this for such a long time gives the engine an opportunity to overheat piston(s), valves (if any) and bearings. There are few other courses where an engine would be required to run at maximum output for such a long time without respite. Closing the throttle for even one or two seconds will do a lot to "rest" an engine; there is no chance to give an engine a breather out on Daytona's oval, and anything that will go the distance there, at front-runner speeds, has established a basic reliability beyond any question.

(Continued on page 24)

TECH.

The enormous strain on the engine was very much in my mind while I was grinding around at Daytona, and I was most anxious to pull the engine down after the race to see what damage, if any, had been done. There was, it developed, surprisingly little. The bearings were, as nearly as I could determine, in perfect condition. Indeed, nothing down in the crankcase or transmission showed any wear not normal to 200 miles of practice and racing. The right-hand cylinder, which was losing most of its charge out the broken expansion chamber was, as might be expected, in quite good condition. But, over in the left cylinder, which had been doing most of the pulling for about 85 racing miles, the extreme temperatures brought by prolonged full-throttle running had taken their toll. Carbonized oil had partially frozen the ring, and "varnished" the piston quite heavily well down on its skirt. Inside, the piston had a cooked-on coat of carbonized oil under the crown, and down as far as the wrist-pin bosses. Also, the cylinder bore had suffered. The TD-IB has allaluminum cylinders with a chromiumplated bore, and there was a small spot up near the top of the bore where the chrome appeared to be worn away. I think this can be blamed on the abnormal temperature, which would virtually destroy lubrication up at the top of the cylinder. Of course, this was the cylinder in which the piston was holed on the first day of practice, and it is entirely possible that a partial seizure at that time started the damage to the cylinder wall. In any case, wear and tear on the engine was surprisingly light after so many racing miles, and preparation for the next race will consist only of new pistons and rings (these parts are ridiculously inexpensive) and a replacement cylinder — and, of course, weldingup that broken expansion chamber. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

June 1965 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

June 1965 By Gary Bray -

Suzuki Watch-It.

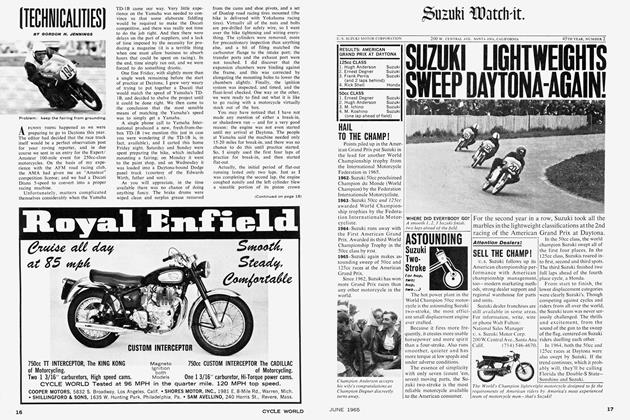

Suzuki Watch-It.Suzuki Lightweights Sweep Daytona-Again!

June 1965 -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1965 -

Cycle World Road Test

Cycle World Road TestYamaha 305 Ym-1 & Big Bear Scrambler

June 1965 -

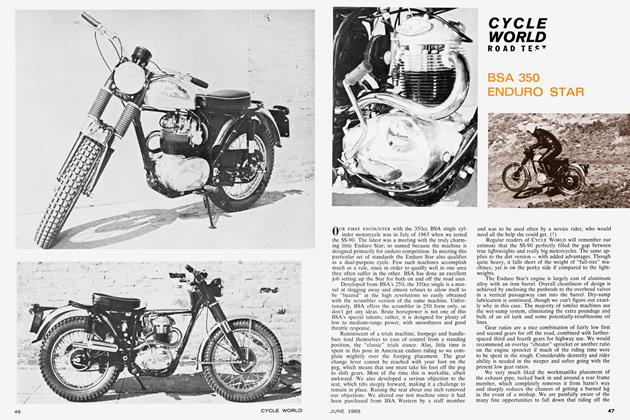

Cycle World

Cycle WorldRoad Test Bsa 350 Enduro Star

June 1965

![[technicalities]](https://cycleworld.blob.core.windows.net/cycleworld19650601thumbnails/Spreads/0x600/9.jpg)