WHEN INDIAN AND HARLEY-DAVIDSON REIGNED SUPREME

THE TALE OF A LITTLE-HERALDED ERA WHEN AMERICAN MOTORCYCLES RULED THE RACING ROOST, BOTH HERE AND ABROAD.

DENNIS MAY

AT BROOKLANDS, the legendary paved speedway at Weybridge, England, which opened in 1907 and folded when Hitler handed around the band parts in '39, a solitary racing motorcycle rusts in an unmarked grave. In April of 1912, a young Englishman, A.J. Moorhouse, lost control of his bike on the Railway Straight, dove off the circuit and smacked a telegraph pole with such force that his goggle frames left imprints in the wood. Moorhouse died instantly, the first rider ever to lose his life at Brooklands. His machine, as CKD as Ozymandias' statue, was rever ently swept into a heap and buried under the fatal pole.

Moorhouse was a loyal Indian de votee and it was fitting that this make, rather than one of its British rivals, should have unstiffened the upper lips of Brookiands officials. In the track's shott lifespan to date, Indian had al ready won the admiration of Brooklands fans and English speedbuffs. And in the two and a half years remaining before the outbreak of World War I, the red rockets from Springfield repeatedly blew the English opposition into the bushes, both on tracks and hilcimbs. It was before the new generation of British J. A.P., Anzani and Blackburne big inchers had gotten into stride. "Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair" boasts came naturally and justifiably to Indian and Harley-Davidson both.

Today, with the U~S./U.K. pecking order reversed, it must be hard for the grandsons of those tungsten-muscled oldtimers to realize that eating dust from tearaway Indian and Harley im ports was the frequent lot of their now aged or departed seniors.

of American iron was so firmly established that no British maker even attempted to field a contender for the era's great leap for ward in two-wheeled velocity. . . goodby two figures, hello three. It was • foreseeable a mile off that the honor of hitting the century mark in Britain for the first time, officia1~y clocked, must fall to either Indian or Harley. It did, too, in circumstances of some drama.

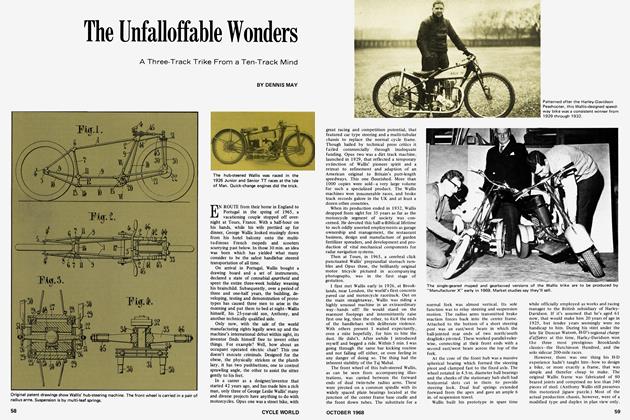

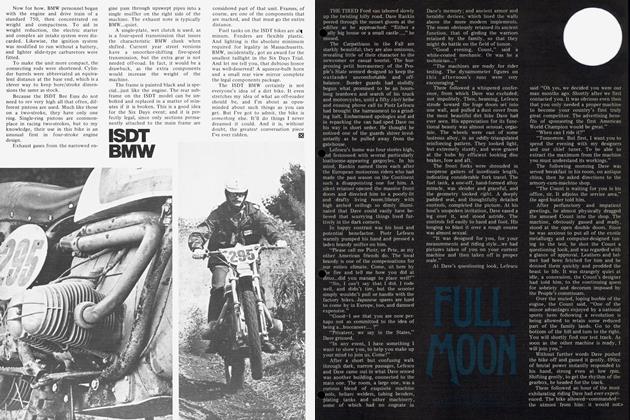

• in personal terms, this was to be a three-way fight, with Bert Le Vack, the Brooklands cam pionissimo of his day, representing Indian, Claude Temple and Douglas Davidson in the opposite corner with Harley-Davidsons. The bikes used were all alike in general configurationshort wheelbase board track racers; as un-english as sauerkraut and forbidding ly unsuitable for the long (2.76 miles), rough-surfaced and asymmetrically banked Weybridge track. In experience of his mount, known locally as the Camel on account of its anti-human tendencies, Le Vack had the edge: he'd first ridden this Indian, a 1911 retread with eight valves, in a short Brooklands race the previous year, and won at an 80-mph average from a standing start. The Harley-Davidsons had been import ed as recently as the winter of 1920-21. It wasn't until they started their work outs for the great century kampf in April 1921 that Temple and Davidson realized what was coming.

The two H-Ds, serial numbered CA 13 and CA 14, were identical-clutchiess, gearless, devoid of fork springs, shod with adder-gauge tires. Temple and Davidson threw a coin for the choice of bikes; Temple won and took CA 14, presumably because CAl 3 sounded kind of unlucky. Years later, Davidson told me, "My khaki rogue gave me such cOncentrated vibromassage that I black ed out as speeds around 100 mph." The only way to start the CA 13, geared as it was for 100-plus mph and with no. clutch, was to roll down the Brooklands Test Hill with the compression release open, then drop it shut at the critical moment.

The Indian and Harleys displaced a mite under 1000 cc or 61 Cu. in., then the limit of the biggest class recognized internationally.

Progress toward the tantalizing 100-mph goal started on Wednesday, April 27, 1921. Temple opened hostil ities with a 97.26-mph burst over the flying start kilometer. (This, like the ensuing runs, was timed one way only, giving the rider the slight benefit of a descending approach to the trap off the Brooklands banking. The immediate aim was a national record only, two-way timing wasn't necessary.)

Later, Le Vack and his Camel upped the bidding to 98.98 mph, failing in repeated efforts to improve on this.

The following day, there was, oldtimers vow, a veritable century smell in the Brookiands air (it must have been strong or you couldn't have isolated it from the omnipresent odor of the track's own sewage farm), Temple and Davidson, each with a do-or-die glint in his eye, were at action stations. Le Vack was temporarily absent, investigating the mystery of why the eight-valver was consistently losing power in the final one third of the kilometer. Temple, winding everything wide open and flat tening his dapper torso along CA 14's tanktop, turned four runs in a row at precisely 99.96 mph, missing out by one fifth of a second.

Finally it was Douglas Davidson's turn, and he made it: 100.76 miles per

Denouement to the story was this: one day later Le Vack showed up to cover a flying kilometer at no less than 106.52 mph. Bert had finally deter mined the reason for his power curve's dropoff: he was using valves made from a new and unfamiliar steel, which called for larger rocker clearances than he'd been allowing.

Features of the eight-valve Indian powerplant included aluminum pis tons-presumably not original 1911 equipment-and a throttleless carbu retort engine control was thus by mag neto kill button only. You had all or nothing. In the board track fashion of the day, the sawed off exhaust pipes, one per pair of valves, terminated about nine inches from the ports. Transmis sion, as on the Harleys, was by two chains via a countershaft."Although the Camel, unlike its H-D competition, boasted spring forks, riding it at Brooklands at 100 per was no less hazardous than taking a long walk along a short pier. It’s doubtful if any British rider except Le Vack could have done it justice in this theater.

Discouraged with CAM’s handling, Temple later switched the potent engine from this bike to his own more or less stock 1915 Harley. The resulting hybrid, with sprung forks, hub clutch and invaluable extra inches of wheelbase,

enabled him to set a world mile record, timed both ways, at exactly 100 mph in September 1921. Technically superior, as it was, to Davidson’s one-way century, this exploit was overshadowed in the public mind by CA 13’s earlier and much fanfared feat. Although by no means a prophet without honor at his home track, debonair Claude Temple was less lionized there than at the Montlhery Autodrome, where his French idolators tagged him Le Prince des GuidonsPrince of the Handlebars.

In case the Davidson, Le Vack and Temple records hadn’t amply demonstrated America’s domination of the Brooklands scene, another 1921 happening certainly did. This was the ever memorable 500-Mile Race, which Le Vack won with ease for Indian at 72.42 mph; Fred Dixon’s Harley placed 2nd. Incidentally the field of 64 starters included an entry by the Duke of York, later to become King George VI.

Not even the courageous and durable Le Vack would have braved 500 racing miles behind the Camel’s laid-back ears, and he wisely opted for Indian’s tamer but more reliable 1000-cc sidevalver of the period. Even then, he had his troubles, like losing 11 laps to punctures and blowouts, plus further delays for spark plug changes. But Davidson, with whom Bert fought a running duel for over half the race, had worse troubles still. With one shoulder weakened by the aftermath of machine gun wounds suffered during WWI, he hadn’t the strength to push his Harley to the pits single-handedly when its engine went sick, and he accepted outside assistance. For this he was disqualified.

But the real hero of the race was rookie Dixon, who’d never ridden Brooklands before training started. It was then that he discovered certain peculiarities in the Harley’s handling. Unbeknownst to him, it was fitted with sidecar type forks, devoid of trail. In efforts to improve man/machine cohesion, he scissored himself a saddleshaped sheet of emery cloth and glued it to the seat, rough side up. As the race wore on the emery wore its way through Fred’s leathers, then through his underpants, finally abrading his rump until it bled. He was brooding the problem of whether to press on or stop and jettison the emery when his front

tire burst, the bike went into a lock to lock wobble and he executed triple somersaults in mid-air. So, perforcedly, Dixon stopped, pushed to the pits, changed the wheel, restarted and finished 2nd. Once again, with American metal filling the two top places, Uncle Sam had rubbed salt in Britannia’s wounds.

A few laps from the end, Le Vack had thrown his household cavalry—and most of all, his wife-into galloping habdabs by “disappearing” on the remote, out-of-sight side of the track. So far from being a casualty, or even, as was feared, morgue fodder, he’d decided his position was secure enough for him to stop off and smoke a cigarette.

Although the British motorcycle industry, in the period that concerns us, produced nothing to match the American invaders in big-barrel racing and record breaking, at least one U.S. factory, Harley-Davidson, generously conceded that at least one Englishman, Douglas Davidson, could out-finger its own tuning virtuosi. H-D consistently consulted Davidson at transocean range on hop-up problems. Once, following his sidecar racing successes with one of their 600-cc fíat Twins, the Milwaukee brass allowed that they “hadn’t managed to beat the speeds in question with this model as a solo.”

As the U.S. was not a member of the FICM (predecessor to the FIM) at this time, statistics on record breaking in America weren’t officially promulgated in Europe. Nor were Europeans disposed to accept American claims unofficially reported east of the ocean. Similarly, when Temple’s 100.0-mph flying mile went on the FIM books as a world record in 1921, Americans just laughed up their sleeves, confident that they had beaten the century, timed both ways, X years earlier.

Be that as it may, it’s interesting that FIM world record listings published early in 1921 credited every last mark in Class I (sidecar hauling 1000-cc bikes) to U.S. makes, ridden by Englishmen; and 17 out of a total of 32 Class E (1000-cc solo) records to the same man/machine combos. Ranging as they did from one kilometer to 12 hours, these operations demonstrated an impartial mastery of everything from Garlitsy sprints to the longest of LPs.

(continued on page 80

Continued from page 64

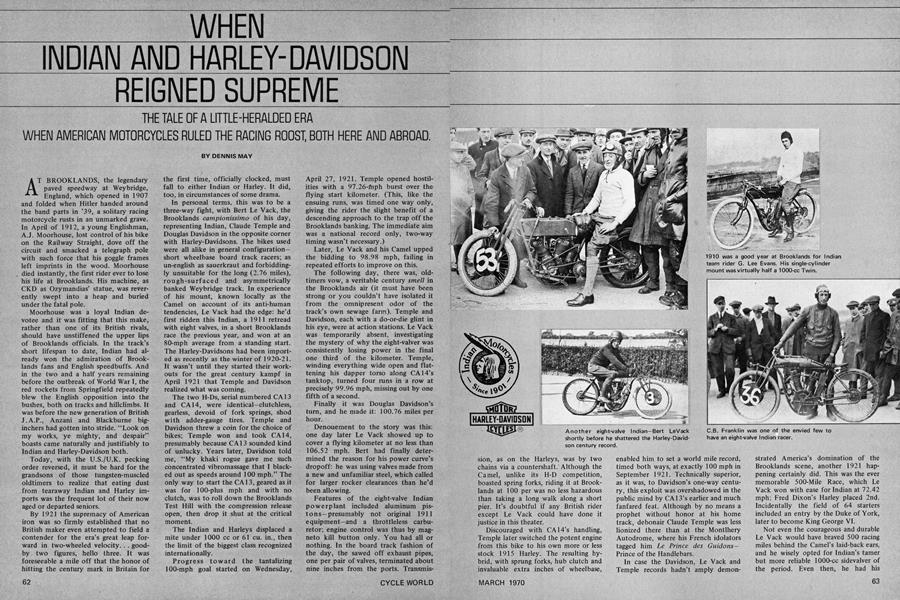

From as early as 1910, three years after the track’s inauguration, Indian riders like G. Lee Evans and Billy Wells had been prominent at Brooklands, their ranks being joined well before WWI broke out by notables such as C.E. Bennet, the ill-fated A.J. Moorhouse and C.B. Franklin. Wells was an American living in England and later headed Indian’s British subsidiary for many years. Franklin was Irish but emigrated to the U.S. where he is thought to have become manager of the parent Indian plant. Oscar Hedstrom, the make’s chief designer, visited Brooklands in 1910 and declared himself “delighted with the many successes his machines had achieved since their introduction to this country.”

If he’d been in England a year later he could have witnessed still another Indian triumph that was to stand Brooklands on its ear, providing its habituées with an infinity of debating material. This was the celebrated international match race between Jake de Rosier (Indian), a contemporary star of the American board tracks, and Britain’s Charlie Collier, riding a product of his family firm, Matchless.

The combatant bikes were both 1000-cc V-twins; the Matchless’s J.A.P. engine had vertical ohv operated by pushrods and the prophetically oversquare measurements of 90 by 77 millimeters. The Indian clockwork, longer than wide at 82 by 93 mm, used the overhead inlet and side exhaust valves that makers then favored. Characteristically laggard in the transmission department, the Matchless had direct belt drive, something that American bikes had abandoned some years earlier and replaced with slip-proof, less fragile chains.

The match was run in three heats, over distances of 5.5, 13.5 and 27 miles. The white-jerseyed, handlebar-moustached Collier led Heat 1 initially but was overtaken and finally beaten by a machine’s length in “one of the most exciting races on record.” Speed: 80.59 mph. In Heat 2, Rosier threw a front tire and dnf’d, Collier finished unopposed and nourished natives’ hopes that the match would go to Matchless. But is wasn’t to be. In a breath-stopping decided, the pair passed and repassed each other until Collier, while leading marginally, paid the penalty for a loose magneto switch. It vibrated to the Off position; while Charlie was occupied with what-can-the-matter-be thoughts, Jake passed and won at 78.64 mph.

“A kindly nation” (meaning Britain) “seems to prefer its heroes slightly unsuccessful,” as Guedalla said, so English protagonists of Collier and Matchless weren’t terribly displeased with their slight lack of success. The significant fact is that the shortest race had been won by de Rosier at the highest speed of the series—proof enough that the Indian’s combination of acceleration and maximum speed was superior to the Matchless’s.

This Brooklands match, staged in July of 1911, was the second de Rosier/Collier confrontation in two months. In the Isle of Man TT in June (the first one ever run over the present Mountain circuit) Collier had battled gamely against the Indian steamroller and placed 2nd, only to be disqualified for refuelling en route, contrary to the rules. De Rosier, too, by a strange coincidence, was disqualified in this, his first and last TT, after heading a field of 67 runners and 20 different makes on the first lap. But the picturesque Jake, wearing black tights and canvas running shoes as aids to personal streamlining, was expendable. Even without his help the red V-twins copped the first three places—O.C. Godfrey, C.B. Franklin, A.J. Moorhouse—a sweep without precedent in TT history. These Indians, again in advance of most of the British competition, had all-chain transmission and two speeds.

Harley never was represented in the TT but Indian didn’t miss a meeting from 1909 through ’23. Its best placements apart from 1911, always in the Senior event, were 2nd in 1914 and ’21, 3rd in 1913 and ’23.

Over the years, Indian used different types of engines for its TT task force: V-twins first, then rearward sloping 500-cc Singles that in effect were sawed off 1000-cc Twins, finally vertical Singles with side valves. Fred Dixon, whose TT rides on Indians contributed a 2nd and a 3rd, might have made it two 2nds if he hadn’t “passed the time adjusting tappets at the roadside” in 1923, reduced to “benumbed resignation” by a race-long deluge of rain.

Indian’s official TT team in 1910, incidentally, had included a quietspoken, bashful young rider called Bentley. This was none other than Walter Owen Bentley, later to become world famous as the founder and head of the Bentley car firm.

Dixon was perhaps the most versatile tuner-rider who ever bent his talents to American machines in Britain. With the independent spirit of the born freelancer, he raced both Indians and Harleys while trading as an H-D dealer in his native Middlesborough, Yorkshire. It’s probable, though not provable, that he was the first Briton to apply the one carb per cylinder principle to a Twin: it

couldn’t be proved because, with characteristic theatricality, he always enclosed the entire gasworks of his eightvalve Harley in a sheet metal muff against prying eyes. At one period, to reduce the weight and friction of Harley-Davidson pistons, he designed and made replacements with their entire skirts deleted. And his pioneering didn’t end here: in the 1922 200-Mile Sidecar Race at Brooklands “the greatest novelty was Dixon’s Harley-Davidson, the sidecar wheel of which was driven by chain off a sprocket attached to a shaft running underneath the sidecar chassis. . . .”

In 1922, at Clipstone Drive, a wellknown sprint strip, he was the first Briton to hit 100 mph, officially timed on a public road. The following year, he hit a two-way 106.8 mph in the Bois de Boulogne, Paris, on his eight-valve H-D. This, though the world’s fastest mile yet on two wheels (the U.S. had meanwhile joined the FIM), was, for some never explained reason, not accepted as a record.

When Le Vack told Billy Wells and his Indians goodby and went over to J.A.P.-engined Zeniths at the end of 1921, Douglas Davidson stepped in and took over a stable of racing Indians that included the old Camel. Ironically, in his next encounter with Le Vack, Davidson beat Bert at Brooklands. Riding either the Camel or an eight-valved sister machine, Davidson came close to death when his saddle pillar broke at around 95 mph during a solo Brooklands event. With practically no strength in his wound-enfeebled shoulder, he was saved by the kneehook with which these board trackers were fitted.

Although the overhead inlet valve Harleys (as opposed to the pentroofed eight-valvers, prized rarities outside of the States) were beginning to look like candidates for the geriatric ward by the early ’20s, there was still life in these veterans. Anything they lacked in speed was more than offset by their fantastic reliability; to win races, especially of the 200-mile order, you have to finish.

The Brooklands curriculum featured both solo and sidecar races, so the local Harley whips had two chances each year to demonstrate high speed staying power than became proverbial. The solo contest, started in 1923, the sidecar race a year before. Launched in ’25, the Hutchinson 100 for the huge and hideous Mellano Trophy went a mere 100 miles, as its name implied, but even this comparatively short distance showed the Harleys and, to a lesser extent, the Indians to advantage.

Also at Brooklands, the late Frank Longman set a personal record by winning the solo 200 twice (1925 and ’27), the Hutchinson 100 once (1925). His Harley also homed him 2nd twice in the solo 200 and 3rd in the Hutch. In all these races, totaling 1000 miles, he had perfectly trouble-free runs, only stopping for fuel and oil. What made Longman’s performanced extra impressive was his bike’s uncanny silence, partly the product of the bike’s high gearing. Contrasting with the stentorian J.A.P.s it frequently beat, it flitted rather than roared around the track. Considering it likely developed no more power in its career than the alloy-piston production sportster introduced by H-D in 1924, it was no slouch. In winning the Hutchinson 100 of ’25 it averaged a whisker under 90 mph, and 86.89 for the solo 200 in 1927.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 81

In contrast with the Brooklands based Harleys of the early ’20s, which seldom came apart and wore like a pig’s nose, the fiery new hemi-headed J.A.P.s alternately left all opposition for dead or blew themselves up. In the 1925 solo 200, for instance, there were only two finishers—Longman 1st, Joe Wright (Zenith-J.A.P.) 2nd and last. Although the J.A.P. machine was maybe 15 mph faster than the Harley when running properly, it averaged a miserable 69.56, compared with the winner’s 85.41.

In the 200-mile sidecar events, American mounted Britishers often dislocated the egos of the J.A.P. contingent, as when Douglas Davidson (Indian) and Tommy Alehin of Australia (H-D) placed 1st and 3rd in the 1922 series’ opener, sandwiching Bert Le Vack (Zenith-J.A.P.); and Dick Humphries won with a Harley-Davidson in ’24 and S.E. Longman’s Indian was 3rd. Although Humphries beat the 2nd place J.A.P. by a resounding 6.79 mph, he had his moments of anxiety: the floor started dropping out of his sidecar; he spent half the race casting agonized glances checking whether his passenger was still with him.

Alas, “All human things are subject to decay, and when fate summons monarchs must obey.” Indian and Harley, long-time monarchs of the Old World racing realm, were as answerable to Dryden’s law as anyone else, and by 1925 the writing was on the wall. Indian had run its last TT. The traditional British hillclimbs on public highways, in which Indian and Harley had so often shared top honors, were outlawed, passing into history. Ominously, at Brooklands, the hitherto almost unstoppable Frank Longman dnfd in two sidecars Hutch 200s in a row, 1925 and ’26.

But it had lasted long and been great while it lasted, this reign of the expatriate Yankees. Bad riddance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

March 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1970 -

Features

FeaturesDoes Your Club Owe Income Tax?

March 1970 By Robert O. Fee -

Competition

CompetitionPolo Without A Feedbag

March 1970 By Heinz-J. Schneider -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

March 1970 By John Dunn