The Unfalloffable Wonders

A Three-Track Trike From a Ten-Track Mind

DENNIS MAY

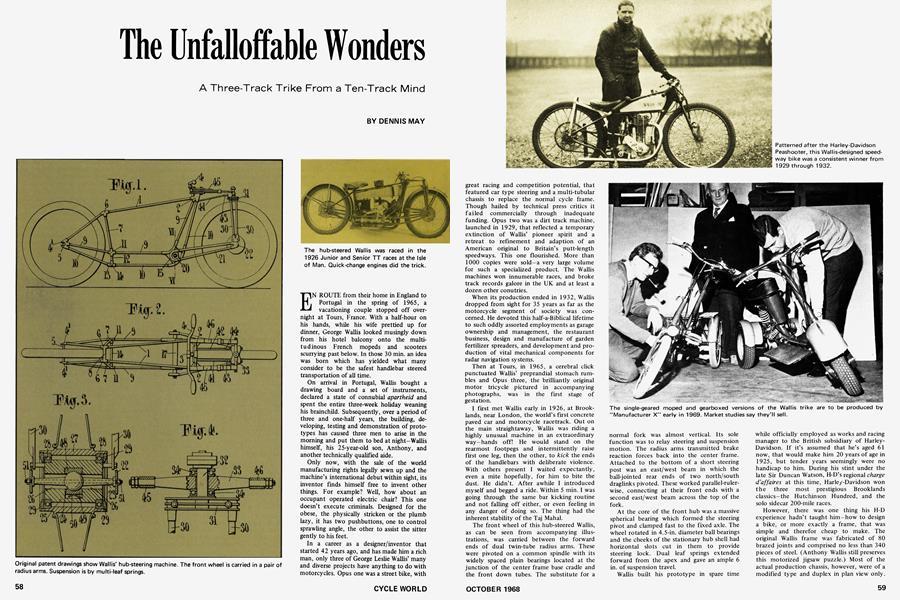

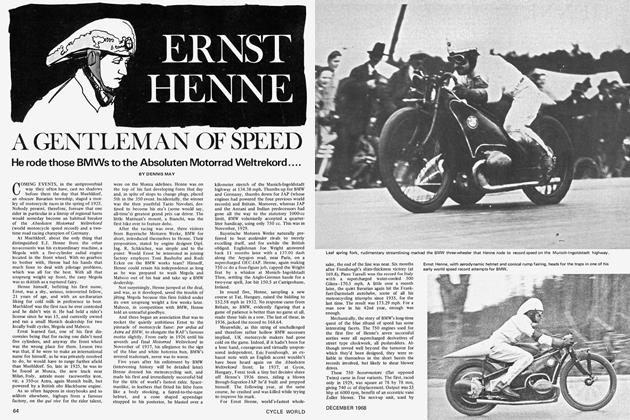

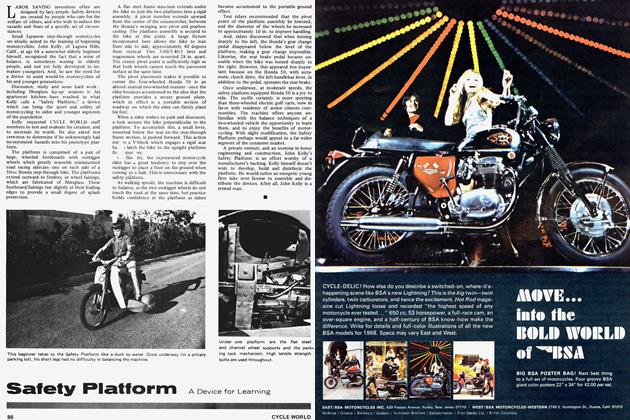

EN ROUTE from their home in England to Portugal in the spring of 1965, a vacationing couple stopped off over-night at Tours, France. With a half-hour on his hands, while his wife prettied up for dinner, George Wallis looked musingly down from his hotel balcony onto the multitudinous French mopeds and scooters scurrying past below. In those 30 min. an idea was born which has yielded what many consider to be the safest handlebar steered transportation of all time.

On arrival in Portugal, Wallis bought a drawing board and a set of instruments, declared a state of connubial apartheid and spent the entire three-week holiday weaning his brainchild. Subsequently, over a period of three and one-half years, the building, developing, testing and demonstration of prototypes has caused three men to arise in the morning and put them to bed at night-Wallis himself, his 25-year-old son, Anthony, and another technically qualified aide.

Only now, with the sale of the world manufacturing rights legally sewn up and the machine’s international debut within sight, its inventor finds himself free to invent other things. For example? Well, how about an occupant operated electric chair? This one doesn’t execute criminals. Designed for the obese, the physically stricken or the plumb lazy, it has two pushbuttons, one to control sprawling angle, the other to assist the sitter gently to his feet.

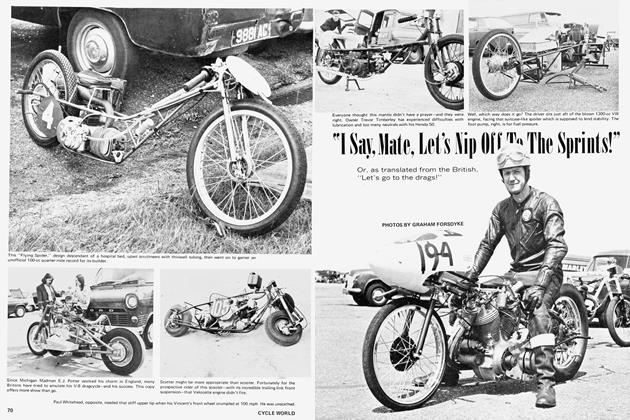

In a career as a designer/inventor that started 42 years ago, and has made him a rich man, only three of George Leslie Wallis’ many and diverse projects have anything to do with motorcycles. Opus one was a street bike, with great racing and competition potential, that featured car type steering and a multi-tubular chassis to replace the normal cycle frame. Though hailed by technical press critics it failed commercially through inadequate funding. Opus two was a dirt track machine, launched in 1929, that reflected a temporary extinction of Wallis’ pioneer spirit and a retreat to refinement and adaption of an American original to Britain’s putt-length speedways. This one flourished. More than 1000 copies were sold-a very large volume for such a specialized product. The Wallis machines won innumerable races, and broke track records galore in the UK and at least a dozen other conutries.

When its production ended in 1932, Wallis dropped from sight for 35 years as far as the motorcycle segment of society was concerned. He devoted this half-a-Biblical lifetime to such oddly assorted employments as garage ownership and management, the restaurant business, design and manufacture of garden fertilizer spreaders, and development and production of vital mechanical components for radar navigation systems.

Then at Tours, in 1965, a cerebral click punctuated Wallis’ preprandial stomach rumbles and Opus three, the brilliantly original motor tricycle pictured in accompanying photographs, was in the first stage of gestation.

I first met Wallis early in 1926, at Brooklands, near London, the world’s first concrete paved car and motorcycle racetrack. Out on the main straightaway, Wallis was riding a highly unusual machine in an extraordinary way-hands off! He would stand on the rearmost footpegs and intermittently raise first one leg, then the other, to kick the ends of the handlebars with deliberate violence. With others present I waited expectantly, even a mite hopefully, for him to bite the dust. He didn’t. After awhile I introduced myself and begged a ride. Within 5 min. I was going through the same bar kicking routine and not falling off either, or even feeling in any danger of doing so. The thing had the inherent stability of the Taj Mahal.

The front wheel of this hub-steered Wallis, as can be seen from accompanying illustrations, was carried between the forward ends of dual twin-tube radius arms. These were pivoted on a common spindle with its widely spaced plain bearings located at the junction of the center frame base cradle and the front down tubes. The substitute for a -normal fork was almost vertical. Its sole function was to relay steering and suspension motion. The radius arms transmitted brake reaction forces back into the center frame. Attached to the bottom of a short steering post was an east/west beam in which the ball-jointed rear ends of two north/south draglinks pivoted. These worked parallel-rulerwise, connecting at their front ends with a second east/west beam across the top of the fork.

At the core of the front hub was a massive spherical bearing which formed the steering pivot and clamped fast to the fixed axle. The wheel rotated in 4.5-in. diameter ball bearings and the cheeks of the stationary hub shell had horizontal slots cut in them to provide steering lock. Dual leaf springs extended forward from the apex and gave an ample 6 in. of suspension travel.

Wallis built his prototype in spare time while officially employed as works and racing manager to the British subsidiary of HarleyDavidson. If it’s assumed that he’s aged 61 now, that would make him 20 years of age in 1925, but tender years seemingly were no handicap to him. During his stint under the late Sir Duncan Watson, H-D’s regional charge d’affaires at this time, Harley-Davidson won the three most prestigious Brooklands classics—the Hutchinson Hundred, and the solo sidecar 200-mile races.

However, there was one thing his H-D experience hadn’t taught him-how to design a bike, or more exactly a frame, that was simple and therefor cheap to make. The original Wallis frame was fabricated of 80 brazed joints and comprised no less than 340 pieces of steel. (Anthony Wallis still preserves this motorized jigsaw puzzle.) Most of the actual production chassis, however, were of a modified type and duplex in plan view only. The prototype, being duplex in plan and side elevation both, was effectively quadruplex, all to no real purpose.

Wallis describes himself as a businessman first, an inventor second, and this hub-steered wonder, unlike all his later enterprises, did not make money-could have, should have, but didn’t. Such finance as Wallis was able to raise was put up by a neighbor of his at Bromley, Kent, one C.G. Underwood, who was, of all things, a lawyer and an etcher, and likely had never ridden a motorcycle in his life. Some of the test sorties were along a steep, ferociously potholed track that flanked the Underwood manse. Wallis was wont to blast down this impossible course, hands off, alternately turning up full power, then making all-on applications of the pedal operated front brake, still hands off. This activity attracted the staid Underwood, who introduced himself to Wallis, and thrust a checkbook into the latter’s face. Wallis Motors, Ltd., was born.

Shortly afterward, while on a visit to his company’s London offshoot, Bill Harley of Harley-Davidson got wind of the Wallis project and, through Sir Duncan Watson, invited George to come to Milwaukee and bring one of his bikes with him. George, unfortunately for him as it was to develop, passed up the opportunity, figuring that in C.G. Underwood he had a bird in the hand. Encouraged by selling an initial batch of 27 machines as fast as he could make them in the converted stable that served as his factory and drawing office, Wallis rented a stand at the 1926 London Motorcycle Show, and there trousered orders for 162 copies. However, demand on this scale, and tooling and expansion necessary to meet it, was outside Underwood’s league. He took fright and put away his wallet. And that was finis for Wallis Motors, Ltd.

The Wallis motorcycle of course wasn’t the first or the last hub-steered motorcycle. The American Ner-a-Car had preceded it and the British OEC-Duplex succeeded it, but George Wallis’ rendering of the principle was the most successful in all-around use. On first acquaintance, some riders found its cornering behavior odd, though this impression, the direst result of the need for an early layover into turns, soon passed. Also, its phenomenal straight running stability, its 100 percent resistance to front wheel wobble, no matter what the provocation, was itself initially disconcerting. A rider suddenly realizing he was about to hit a rock the size of his head at 50 mph couldn’t help bracing himself for the shock, whereas there was nothing this bike abhorred so much as Wrists of Steel. A contemporary Motor Cycle test report said, “It feels safer when ridden hands-off than when steered.” To effect way-down concentration of the main weight masses, engines of 1AP or Blackburne make were fitted at a steep forward slope. The center of gravity was possibly the lowest in motorcycle history. The Wallis was raced in the lunior and Senior TTs of 1926, with a 350-to-500 engine transplant between events. The engine/gearbox aggregate, held together by plates, could be removed bodily from the frame in less than 5 min.

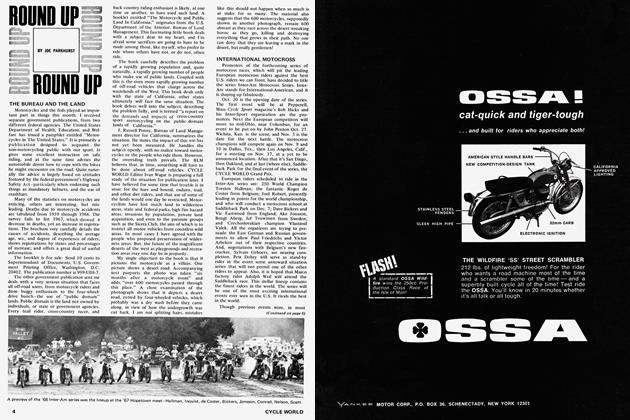

After falling on his face with the hub steerer, at a time when motorcycle trade was booming in Britain, George Wallis two years later landed on his feet-during the worst depression in history-with his dirt tracker. His earlier connection with Harley-Davidson had nothing to do with the fact that in 1928, when he built his speedway prototype, he picked on the H-D Peashooter as the subject for counterfeit. At this date, it was predictable that war to the death was about to be fought on the British speedways between two polarly opposite types of motorcycle—the smooth engined, long-wheelbase flat Twin Douglases on the one hand, and the shorter framed and deeper digging Singles on the other. Wallis foresaw that the latter would win out (which they decisively did), and there was only one Single worth copying—the Peashooter. To be fair, though, Wallis improved as he copied. This Harley, designed for U.S. tracks that ranged between one-quarter and one-half mile, was overly long in the wheelbase for British lap lengths, which varied from approximately 380 to 440 yards.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 60

Wallis’ bike therefore was some 2 in. shorter than the Peashooter. Moreover, it embodied a pet theory of George’s, namely, that the thing to aim for was great rigidity in the center frame area, but a calculated degree of flexibility between this and the rear end triangle. It worked. The machine didn’t lend itself to the Douglas type riding style that was such a surefire crowd puller-a midtrack or even wider itinerary through the turns, every last inch of correcting lock warped on, and the inside handle grip practically plowing the cinders. The object, however, was to win races, wasn’t it? The shortest distance between two peripheral points was around the track’s inner edge, and that’s where the biddable Wallis stuck, making more speed with less haste.

On its prototype test at Crystal Palace, one of London’s leading speedways, the Wallis undercut the track record, and thereafter it just couldn’t stop winning races. Pre-Wallis, British riders had owned and been responsible for the maintenance and tuning of their bikes, but the Crystal Palace promoters were so enamored of George’s new baby that they forthwith bought a full team quota of eight machines and set up their own workshop and communal transportation facilities. This system was soon copied by all rival tracks.

Backed as he was by one of England’s major motorcycle dealerships, Comerfords, Ltd., George never had a financial care during the four years that his dirt tracker was produced. The bike was supplied sans engine, leaving it up to the customer whether he installed a Rudge, a JAP, a Blackbume or whatever. In or around 1931, Frank Arthur, an Australian topliner of his day, set a world quarter-mile speedway record at the Exhibition Grounds, Melbourne, that remains unbroken today-52.5 mph. As the track has since been obliterated by box-like houses, it isn’t likely to be broken now.

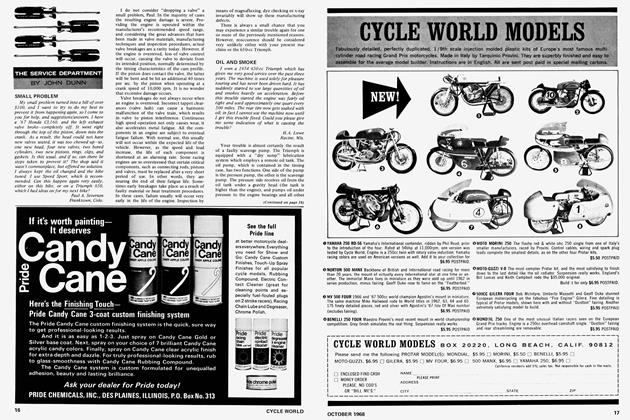

Opus three, the motor tricycle, doesn’t have a name yet, or rather its name can’t be disclosed. This is because George has sold his entire rights in the invention, and the buyer, one of Britain’s oldest and most famous motorcycle makers, isn’t ready to show his hand. The launch is slated for March 1969. The fact of the machine’s existence, and descriptions and photographs of it, have already been published in the world press, including such unlikely publications as the New York News “Coloroto Magazine,’’ and some of its counterparts in Britain and continental Europe. Attention originally was focused on the trike and its creator through a television feature that the British Broadcasting Corp. presented on “Tomorrow’s World,” a science series which the nation’s inventors regard as the heaven above seventh. What is news, however, or was when this was written, is Wallis’ deal with the perforcedly anonymous Manufacturer X and the latter’s intention to go into volume production next March.

The machine will be marketed initially in two forms-one, a moped, i.e., an ultralight vehicle with pedals to put the machine into motion and fire up the engine, and the other a rather heavier, more powerful and faster machine, without pedals and with a more elaborate transmission. Crux of the design, common to both models, and also to a third variant which is still under development and remains Wallis’ property, is its articulation on a plain bushed bearing at the point where the main frame meets a subframe carrying the rear wheels and engine/gear unit. This pivot enables the whole forepart of the machine to be independently laid over on corners, while the two rear wheels remain perpendicular to the pavement, equally loaded under all conditions. The unique geometry involved can best be grasped from a head-on view of the trike making a turn.

Safety which surpasses anything hitherto available to riders, no matter what they might be prepared to pay for it, was the ideal for which Wallis aimed and, according to a test report by the British Scooter Weekly, he’s achieved it. Says the magazine, “Riding the tricycle is just like being on a normal scooter except that you can’t fall off. It is fantastically maneuverable and will almost turn around in its own length.” Skid resistance, a direct function of the right-angle relationship of the rear wheels with the road, is extremely high. If the machine is ridden in tightening circles on a low-grip surface, with all the available power on and the bankable component fully banked (about 40 degrees to the vertical is its limit), the breakaway, when it comes, occurs simultaneously at front and rear ends. Those who so desire can lay into a banking attitude while traveling in a straight line.

The suspension, per se, uses a single coil spring which abuts at its anchored end against an upswept, rearward extension of the main frame backbone tube. There are also two stabilizer springs, again coils and set roughly east/west, that cushion the banking motion and have a precalculated servo effect as the machine straightens up after a corner. Associated with them is a frictional locking device, controlled by a pedal which projects through one of the footboards, that when required holds the center frame in an upright position. Halted in traffic, the rider depresses this pedal and keeps his feet comfortably planted on the footboards—the trike can’t lean either way until he releases the pedal to get underway again.

If the halt occurs on a gradient, there’s a parking brake controlled by a handlebar trigger to take care of gravity. This has its use too, of course, when parking on slopes.

Isolated as it is from any shocks taken by the rear wheels, the center frame is very lightly constructed, so the trike can be thrown around with an abandon that is a barrel of fun for a showoff. More importantly, this feature contributes to the extreme ease of handling that will appeal to timid, elderly or novice riders. If the rider brakes hard enough to lock all wheels, or just the rear ones, on ice or any slippery surface, the trike slides to a standstill in a straight line.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 82

During the phase of the development program that was carried out by G.L. Wallis and Son, Ltd., George’s present company, French Mobilette engines were used. These are 49-cc Single two-strokes. In production, the trikes of both types, moped and scooter, will have engine/transmission units that have been specially designed for them by Manufacturer X. These, too, are 49-cc two-strokers, which incorporate a raft of advanced features. George always has hated noise. For this reason his prototype trikes were silenced to an uncanny degree. Secret of the soto voce effect was an asbestos lined expansion chamber, an idea that he’d used originally in 1926 on the hub-steerer. It remains to be seen whether production models exhale through asbestos.

The moped model is single-geared, but has an automatic (centrifugal) clutch, and is designed to go 25 mph, all day, every day, if necessary. The heavier machine, with the same sized engine in a more vigorous state of tune, has a maximum of '45 mph—again synonymous with cruising speed-and four speeds. With its automatic clutch, shifts are just a matter of moving a tiny lever from one notch to the next.

At present the trikes aren’t equipped with independent rear suspension. The engine/gear or engine/clutch units are part of the unsprung mass. This keeps the engineering simple and will help to hold selling prices to low levels. In any case, the materials used for the power packs make them so light that little would be gained at speeds up to 45 mph by giving them a sprung location. Wallis says that some time in the future, when his present high pressure collaboration with Manufacturer X has tapered off, he may go to work on a racing trike. This would have independent rear springing and a sprung engine of considerably more than 49 cc displacement.

I know, but cannot reveal, the size of the sum spent by X on relevant market research before making its bid for George’s invention, and the same goes for the cost of tooling up for production. Both amounts are astronomical by the normal standards of the cycle and scooter world. The fact that there was a market research program is quite something, for it’s notorious that British manufacturers, regardless of their field, usually prefer to rely on the sales of an article, or the lack of them, to tell them whether a worthwhile demand exists. In this case, perhaps X was trying to keep up with the Far East Joneses, for one of Japan’s motorcycle Big Three (who certainly wouldn’t have neglected market research) was hotly in the running for the unfalloffable wonder.

If genius is “simply knowing the use of tools,” as Johnson said, George Wallis is, for my money, a genius. Busier now with tools and drawing board than ever before in his 60 some years of life, he won’t be easing himself into his own electric chair for many years to come.